Samuel Ward (American statesman)

Samuel Ward (May 25, 1725 – March 26, 1776) was an American farmer, politician, Supreme Court Justice, Governor of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, and delegate to the Continental Congress. He was the son of Rhode Island governor Richard Ward, was well-educated, and grew up in a large Newport, Rhode Island family. After marrying, he and his wife received property in Westerly, Rhode Island from his father-in-law, and the couple settled there and took up farming. He entered politics as a young man and soon took sides in the hard-money vs. paper-money controversy, favoring hard money or specie. His primary rival over the money issue was Providence politician Stephen Hopkins, and the two men became bitter rivals—and the two also alternated as governors of the Colony for several terms.

Samuel Ward Sr. | |

|---|---|

Samuel Ward | |

| 31st and 33rd Governor of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations | |

| In office 1762–1763 | |

| Preceded by | Stephen Hopkins |

| Succeeded by | Stephen Hopkins |

| In office 1765–1767 | |

| Preceded by | Stephen Hopkins |

| Succeeded by | Stephen Hopkins |

| 7th Chief Justice of the Rhode Island Supreme Court | |

| In office May 1761 – May 1762 | |

| Preceded by | John Gardner |

| Succeeded by | Jeremiah Niles |

| Personal details | |

| Born | May 25, 1725 Newport, Rhode Island |

| Died | March 26, 1776 (aged 50) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Resting place | Common Burying Ground, Newport |

| Spouse(s) | Anne Ray |

| Parents | Richard Ward, Mary Tillinghast |

| Occupation | Farmer, Politician, Chief Justice, Governor |

During this time of political activity, Ward became a founder and trustee of Brown University. The most contentious issue that he faced during his three years as governor involved the Stamp Act, which had been passed by the British Parliament just before he took office for the second time. The Stamp Act placed a tax on all official documents and newspapers, infuriating the American colonists by being done without their consent. Representatives of the colonies met to discuss the act but, when it came time for the colonial governors to take a position, Ward was the only one who stood firm against it, threatening his position but bringing him recognition as a great patriot.

Ward's final term as governor ended in 1767, after which he retired to work on his farm in Westerly. However, he was called back into service in 1774 as a delegate to the Continental Congress. War was looming with England, and to this end he devoted all of his energy. After hostilities began, Ward stated, "'Heaven save my country,' is my first, my last, and almost my only prayer." He died of smallpox during a meeting of the Congress in Philadelphia, three months before the signing of the American Declaration of Independence, and was buried in a local cemetery. His remains were later re-interred in the Common Burying Ground in Newport.

Ancestry and early life

Ward was born in Newport in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations in 1725, the son of Rhode Island colonial governor Richard Ward. His mother Mary Tillinghast was the daughter of John Tillinghast and Isabel Sayles, and a granddaughter of Pardon Tillinghast who had come from Seven Cliffs, Sussex, England.[1] She was also a granddaughter of John Sayles and Mary Williams, and a great granddaughter of Rhode Island founder Roger Williams, making Ward the great great grandson of the colony's founder.[2] Ward's great grandfather John Ward was born in Gloucester, England and had been an officer in Oliver Cromwell army, but he came to the American colonies following the accession of King Charles II to the English throne.[3]

Ward was the ninth of 14 children.[4] He grew up in a home of liberal tastes and cultivated manners, and he was trained under the discipline and instruction of a celebrated grammar school in his home town.[5] He may also have been tutored by his older brother Thomas, who had graduated from Harvard College in 1733.[5] As a young man, Ward married Anne Ray, the daughter of a well-to-do farmer on Block Island, from whom the couple received land in Westerly where they settled as farmers.[5] He devoted much effort to improving the breeds of domestic animals, and he raised a breed of racehorse known as the Narraganset pacer.[5]

Family and legacy

Samuel and Anna Ward had eleven children. Their second son Samuel Ward, Jr. served as the lieutenant colonel of the 1st Rhode Island Regiment in the Continental Army. A great-granddaughter was Julia Ward Howe who composed the "Battle Hymn of the Republic". Ward's aunt Mary Ward married Sion Arnold, a grandson of Governor Benedict Arnold.[4]

In 1937, the town of Westerly honored Ward's memory by dedicating its high school to him. It was renamed Westerly High School in the late 20th century, but the main auditorium was given his name.

Ward left a dressing table to his son Samuel Ward, Jr.. The dressing table is now with the Chipstone Foundation in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The table is an example of Queen Anne style furniture. It was made in 1746 by the cabinetmaker Job Townsend, Sr, who worked with his brother Christopher Townsend in Newport, Rhode Island.[6]

Political life

Ward first became active in politics in 1756 when he was elected as a Deputy from Westerly.[7] The divisive political issue of the day was the use of hard money (or specie) versus the use of paper money, and Ward sided with the former group. His chief rival was Stephen Hopkins of Providence who sided with the paper money view.[7] So bitter was the animosity between these two men that Hopkins commenced an action for slander against Ward. The case was moved to Massachusetts for a fair trial, and the judgment went against Hopkins by default in 1759.[7]

For ten years, the two men went back and forth as governor of the colony, each at the head of a powerful party. Josias Lyndon was elected as a compromise candidate in 1768, and the constant butting heads stopped.[7] Hopkins won the election as governor in 1758, and beat Ward again in the following three elections.[7] In 1761, the Assembly named Ward to the office of Chief Justice of the Rhode Island Supreme Court,[7] but he only served in this capacity for a year, finally being elected governor in 1762.[8] During this first year in office, the plan was discussed of founding a college in the Rhode Island colony, and it received Ward's hearty support.[8] He took an active part in the establishment of "Rhode island College," later Brown University. When the school was incorporated in 1765, he was one of the trustees and one of its most generous supporters.[8]

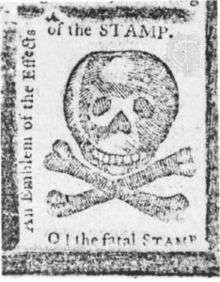

Stamp Act

In 1763 Hopkins once again beat out Ward in the election for governor, serving for the next two years. However, in 1765 Ward for the second time won the contest between the two men. During this term one of the most contentious issues of the age arose, uniting the divided elements into a common cause.[8] Two months before Ward's election the Stamp Act was passed by both houses of the Parliament of Great Britain.[8] This act was a scheme for taxing the colonies, directing that all commercial and legal documents, to be valid in a court of law, must be written on stamped paper sold at fixed prices by governmental officers, and also directing that a duty be applied to newspapers.[8] Parliament, assuming the right to tax the colonies put additional duties on sugar, coffee and other articles. The government also required that lumber and iron from the colonies only be exported to England.[8]

The news of the act infuriated the colonists. Samuel Adams of Massachusetts invited all the colonies to a congress of delegates to meet in New York to discuss relief from the unjust taxes.[8] In August 1765 the Rhode Island General Assembly passed resolutions following the lead of Patrick Henry of Virginia. Rhode Island's appointed stamp distributor, Attorney General Augustus Johnson, refused to execute his office "against the will of our Sovereign Lord the People."[8] The Rhode Island General Assembly met again at East Greenwich in September 1765, choosing delegates to the New York congress, and appointing a committee to consider the Stamp Act.[9] The committee reported six resolutions that pointed to the absolution of allegiance to the British Crown unless the grievances were removed.[9]

The day before the act was to become effective, all of the royal governors took an oath to sustain it. Among the colonial governors, only Samuel Ward of Rhode Island refused the act.[9] In so doing, he forfeited his position, and was threatened with a huge fine, but this did not deter him.[9] Ultimately, the act was repealed, with news reaching the colonies in May 1766 to public rejoicing.[10] The conflict for independence was delayed, but not abandoned.

Continental Congress

Samuel Ward

In the 1767 election Ward once again lost to his nemesis, but Hopkins would not seek re-election after 1768. Eventually, friendly relations between the two great rivals was established.[10] The famous controversy was replaced by a more momentous struggle soon to involve the colony.[10] Governor Ward retired to his estate in Westerly, but became active again in 1774. At a town meeting in May of that year, the freemen of Providence formally proposed a Continental Congress for the union of the colonies, the first such act in favor of this measure, though the idea had already been circulating in several of the colonies.[10] As plans solidified, the General Assembly met the following month in Newport and elected Samuel Ward and Stephen Hopkins as delegates to congress.[10]

Ward served on several important committees, including the Committee on Secrets and frequently sat in the chair when the Congress met as a committee of the whole. He devoted all of his energy to the Continental Congress, until his untimely death from smallpox at a meeting of the convention in Philadelphia. Ward died a little more than three months before the Declaration of Independence was signed.[10] He was originally buried in Philadelphia, but in 1860 was reinterred in the Common Burying Ground in Newport, Rhode Island.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Samuel Ward (American statesman) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- Austin 1887, p. 202.

- Austin 1887, p. 370.

- Austin 1887, p. 406.

- Austin 1887, p. 407.

- Bicknell 1920, p. 1073.

- "Dressing Table, RIF339". The Rhode Island Furniture Archive at the Yale University Art Gallery. Retrieved December 11, 2019.

- Bicknell 1920, p. 1074.

- Bicknell 1920, p. 1075.

- Bicknell 1920, p. 1076.

- Bicknell 1920, p. 1077.

Bibliography

- Arnold, Samuel Greene (1894). History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Vol.2. Providence: Preston and Rounds.

- Austin, John Osborne (1887). Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island. Albany, New York: J. Munsell's Sons. ISBN 978-0-8063-0006-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bicknell, Thomas Williams (1920). The History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Vol.3. New York: The American Historical Society. pp. 1073–8.

- "The History of Westerly / Ward Senior High School". Westerly High School. Archived from the original on October 28, 2008. Retrieved March 14, 2009. The material used in this article has been removed from the website.

Further reading

- Smith, Joseph Jencks (1900). Civil and Military List of Rhode Island, 1647–1800. Providence, RI: Preston and Rounds, Co.

External links

- Biographic sketch at U.S. Congress website

- The Library of Congress American Memory Collection, Letters of the Delegates to Congress - Volumes 1–3 contain his letters to his children and the diaries he kept of events at the Congress; these tell Ward's story poignantly.

- Brown University Charter

- Chronological list of Rhode Island leaders

- Samuel Ward at Find a Grave