Parchment

Parchment is a writing material made from specially prepared untanned skins of animals—primarily sheep, calves, and goats. It has been used as a writing medium for over two millennia. Vellum is a finer quality parchment made from the skins of young animals such as lambs and young calves.

It may be called animal membrane by libraries and museums that wish to avoid distinguishing between "parchment" and the more-restricted term "vellum" (see below).

Parchment and vellum

Today the term "parchment" is often used in non-technical contexts to refer to any animal skin, particularly goat, sheep or cow, that has been scraped or dried under tension. The term originally referred only to the skin of sheep and, occasionally, goats. The equivalent material made from calfskin, which was of finer quality, was known as "vellum" (from the Old French velin or vellin, and ultimately from the Latin vitulus, meaning a calf);[1] while the finest of all was "uterine vellum", taken from a calf foetus or stillborn calf.

Some authorities have sought to observe these distinctions strictly: for example, lexicographer Samuel Johnson in 1755, and master calligrapher Edward Johnston in 1906.[2] However, when old books and documents are encountered it may be difficult, without scientific analysis, to determine the precise animal origin of a skin either in terms of its species, or in terms of the animal's age.[3] In practice, therefore, there has long been considerable blurring of the boundaries between the different terms. In 1519, William Horman wrote in his Vulgaria: "That stouffe that we wrytte upon, and is made of beestis skynnes, is somtyme called parchement, somtyme velem, somtyme abortyve, somtyme membraan."[4] In Shakespeare's Hamlet (written c. 1599–1602) the following exchange occurs:

Hamlet. Is not parchment made of sheepskins?

Horatio. Ay, my lord, and of calves' skins too.[5]

Lee Ustick, writing in 1936, commented that:

To-day the distinction, among collectors of manuscripts, is that vellum is a highly refined form of skin, parchment a cruder form, usually thick, harsh, less highly polished than vellum, but with no distinction between skin of calf, or sheep, or of goat.[6]

It is for these reasons that many modern conservators, librarians and archivists prefer to use either the broader term "parchment", or the neutral term "animal membrane".[7][8]

History

The word parchment evolved (via the Latin pergamenum and the French parchemin) from the name of the city of Pergamon, which was a thriving center of parchment production during the Hellenistic period.[9] The city so dominated the trade that a legend later arose which said that parchment had been invented in Pergamon to replace the use of papyrus which had become monopolized by the rival city of Alexandria. This account, originating in the writings of Pliny the Elder (Natural History, Book XII, 69–70), is dubious because parchment had been in use in Anatolia and elsewhere long before the rise of Pergamon.[10]

Herodotus mentions writing on skins as common in his time, the 5th century BC; and in his Histories (v.58) he states that the Ionians of Asia Minor had been accustomed to give the name of skins (diphtherai) to books; this word was adapted by Hellenized Jews to describe scrolls.[11] In the 2nd century BC, a great library was set up in Pergamon that rivaled the famous Library of Alexandria. As prices rose for papyrus and the reed used for making it was over-harvested towards local extinction in the two nomes of the Nile delta that produced it, Pergamon adapted by increasing use of parchment.[12]

Writing on prepared animal skins had a long history, however. David Diringer noted that "the first mention of Egyptian documents written on leather goes back to the Fourth Dynasty (c. 2550–2450 BC), but the earliest of such documents extant are: a fragmentary roll of leather of the Sixth Dynasty (c. 24th century BC), unrolled by Dr. H. Ibscher, and preserved in the Cairo Museum; a roll of the Twelfth Dynasty (c. 1990–1777 BC) now in Berlin; the mathematical text now in the British Museum (MS. 10250); and a document of the reign of Ramses II (early thirteenth century BC)."[13] Though the Assyrians and the Babylonians impressed their cuneiform on clay tablets, they also wrote on parchment from the 6th century BC onward. Rabbinic literature traditionally maintains that the institution of employing parchment made of animal hides for the writing of ritual objects such as the Torah, mezuzah, and tefillin is Sinaitic in origin, with special designations for different types of parchment such as gevil and klaf.[14]

Early Islamic texts are also found on parchment.

In the later Middle Ages, especially the 15th century, parchment was largely replaced by paper for most uses except luxury manuscripts, some of which were also on paper. New techniques in paper milling allowed it to be much cheaper than parchment; it was made of textile rags and of very high quality. With the advent of printing in the later fifteenth century, the demands of printers far exceeded the supply of animal skins for parchment.

There was a short period during the introduction of printing where parchment and paper were used at the same time, with parchment (in fact vellum) the more expensive luxury option, preferred by rich and conservative customers. Although most copies of the Gutenberg Bible are on paper, some were printed on parchment; 12 of the 48 surviving copies, with most incomplete. In 1490, Johannes Trithemius preferred the older methods, because "handwriting placed on parchment will be able to endure a thousand years. But how long will printing last, which is dependent on paper? For if ... it lasts for two hundred years that is a long time."[15] In fact high quality paper from this period has survived 500 years or more very well, if kept in reasonable library conditions.

The heyday of parchment use was during the medieval period, but there has been a growing revival of its use among artists since the late 20th century. Although parchment never stopped being used (primarily for governmental documents and diplomas) it had ceased to be a primary choice for artist's supports by the end of 15th century Renaissance. This was partly due to its expense and partly due to its unusual working properties. Parchment consists mostly of collagen. When the water in paint media touches parchment's surface, the collagen melts slightly, forming a raised bed for the paint, a quality highly prized by some artists.

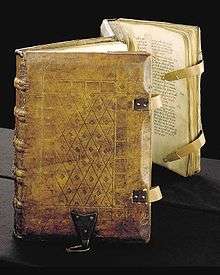

Parchment is also extremely affected by its environment and changes in humidity, which can cause buckling. Books with parchment pages were bound with strong wooden boards and clamped tightly shut by metal (often brass) clasps or leather straps;[16] this acted to keep the pages pressed flat despite humidity changes. Such metal fittings continued to be found on books as decorative features even after the use of paper made them unnecessary.[16]

Some contemporary artists prize the changeability of parchment, noting that the material seems alive and like an active participant in making artwork. To support the needs of the revival of use by artists, a revival in the art of preparing individual skins is also underway. Hand-prepared skins are usually preferred by artists because they are more uniform in surface and have fewer oily spots which can cause long-term cracking of paint than mass-produced parchment, which is usually made for lamp shades, furniture, or other interior design purposes.[17]

The radiocarbon dating techniques that are used on papyrus can be applied to parchment as well. They do not date the age of the writing but the preparation of the parchment itself.[18] While it is feasibly possible also to radio carbon date certain kinds of ink, it is extremely difficult to do due to the fact that they are generally present on the text only in trace amounts, and it is hard to get a carbon sample of them without the carbon in the parchment contaminating it.[19]

Manufacture

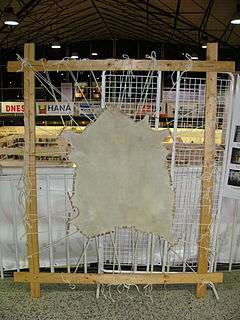

Parchment is prepared from pelt – i.e. wet, unhaired, and limed skin – by drying at ordinary temperatures under tension, most commonly on a wooden frame known as a stretching frame.[20]

Skinning, soaking, and dehairing

After being flayed, the skin is soaked in water for about a day. This removes blood and grime from the skin and prepares it for a dehairing liquor.[21] The dehairing liquor was originally made of rotted, or fermented, vegetable matter, like beer or other liquors, but by the Middle Ages an unhairing bath included lime. Today, the lime solution is occasionally sharpened by the use of sodium sulfide. The liquor bath would have been in wooden or stone vats and the hides stirred with a long wooden pole to avoid human contact with the alkaline solution. Sometimes the skins would stay in the unhairing bath for eight or more days depending how concentrated and how warm the solution was kept – unhairing could take up to twice as long in winter. The vat was stirred two or three times a day to ensure the solution's deep and uniform penetration. Replacing the lime water bath also sped the process up. However, if the skins were soaked in the liquor too long, they would be weakened and not able to stand the stretching required for parchment.[21]

Stretching

After soaking in water to make the skins workable, the skins were placed on a stretching frame. A simple frame with nails would work well in stretching the pelts. The skins could be attached by wrapping small, smooth rocks in the skins with rope or leather strips. Both sides would be left open to the air so they could be scraped with a sharp, semi-lunar knife to remove the last of the hair and get the skin to the right thickness. The skins, which were made almost entirely of collagen, would form a natural glue while drying and once taken off the frame they would keep their form. The stretching aligned the fibres to be more nearly parallel to the surface.

Treatments

To make the parchment more aesthetically pleasing or more suitable for the scribes, special treatments were used. According to Reed there were a variety of these treatments. Rubbing pumice powder into the flesh side of parchment while it was still wet on the frame was used to make it smooth and to modify the surface to enable inks to penetrate more deeply. Powders and pastes of calcium compounds were also used to help remove grease so the ink would not run. To make the parchment smooth and white, thin pastes (starchgrain or staunchgrain) of lime, flour, egg whites and milk were rubbed into the skins.[22]

Meliora di Curci in her paper "The History and Technology of Parchment Making" notes that parchment was not always white. "Cennini, a 15th-century craftsman provides recipes to tint parchment a variety of colours including purple, indigo, green, red and peach."[23] The Early medieval Codex Argenteus and Codex Vercellensis, the Stockholm Codex Aureus and the Codex Brixianus give a range of luxuriously produced manuscripts all on purple vellum, in imitation of Byzantine examples, like the Rossano Gospels, Sinope Gospels and the Vienna Genesis, which at least at one time are believed to have been reserved for Imperial commissions.

Many techniques for parchment repair exist, to restore creased, torn, or incomplete parchments.

Reuse

Between the seventh and the ninth centuries, many earlier parchment manuscripts were scrubbed and scoured to be ready for rewriting, and often the earlier writing can still be read. These recycled parchments are known as palimpsests. Later, more thorough techniques of scouring the surface irretrievably lost the earlier text.

Jewish parchment

The way in which parchment was processed (from hide to parchment) has undergone a tremendous evolution based on time and location. Parchment and vellum are not the sole methods of preparing animal skins for writing. In the Babylonian Talmud (Bava Batra 14B) Moses writes the first Torah Scroll on the unsplit cow-hide called gevil.

Parchment is still the only medium used by traditional religious Jews for Torah scrolls or tefilin and mezuzahs, and is produced by large companies in Israel. For those uses, only hides of kosher animals are permitted. Since there are many requirements for it being fit for the religious use, the liming is usually processed under supervision of a qualified Rabbi.[24]

Additional uses of the term

In some universities, the word parchment is still used to refer to the certificate (scroll) presented at graduation ceremonies, even though the modern document is printed on paper or thin card; although doctoral graduates may be given the option of having their scroll written by a calligrapher on vellum. The University of Notre Dame still uses animal parchment for its diplomas. Similarly, Heriot-Watt University uses goatskin parchment for their degrees.

Plant-based parchment

Vegetable (paper) parchment is made by passing a waterleaf (an unsized paper like blotters) made of pulp fibers into sulfuric acid. The sulfuric acid hydrolyses and solubilises the main natural organic polymer, cellulose, present in the pulp wood fibers. The paper web is then washed in water, which stops the hydrolysis of the cellulose and causes a kind of cellulose coating to form on the waterleaf. The final paper is dried. This coating is a natural non-porous cement, that gives to the vegetable parchment paper its resistance to grease and its semi-translucency.

Other processes can be used to obtain grease-resistant paper, such as waxing the paper or using fluorine-based chemicals. Highly beating the fibers gives an even more translucent paper with the same grease resistance. Silicone and other coatings may also be applied to the parchment. A silicone-coating treatment produces a cross-linked material with high density, stability and heat resistance and low surface tension which imparts good anti-stick or release properties. Chromium salts can also be used to impart moderate anti-stick properties.

Parchment craft

Historians believe that parchment craft originated as an art form in Europe during the fifteenth or sixteenth centuries. Parchment craft at that time occurred principally in Catholic communities, where crafts persons created lace-like items such as devotional pictures and communion cards. The craft developed over time, with new techniques and refinements being added. Until the sixteenth century, parchment craft was a European art form. However, missionaries and other settlers relocated to South America, taking parchment craft with them. As before, the craft appeared largely among the Catholic communities. Often, young girls receiving their first communion received gifts of handmade parchment crafts.

Although the invention of the printing press led to a reduced interest in hand made cards and items, by the eighteenth century, people were regaining interest in detailed handwork. Parchment cards became larger in size and crafters began adding wavy borders and perforations. In the nineteenth century, influenced by French romanticism, parchment crafters began adding floral themes and cherubs and hand embossing.

Parchment craft today involves various techniques, including tracing a pattern with white or colored ink, embossing to create a raised effect, stippling, perforating, coloring and cutting. Parchment craft appears in hand made cards, as scrapbook embellishments, as bookmarks, lampshades, decorative small boxes, wall hangings and more.

DNA testing

An article published in 2009 by Timothy L. Stinson considered the possibilities of tracing the origin of medieval parchment manuscripts and codices through DNA analysis. The methodology would employ polymerase chain reaction to replicate a small DNA sample to a size sufficiently large for testing. A 2006 study had revealed the genetic signature of several Greek manuscripts to have "goat-related sequences". It might be possible to use these techniques to determine whether related library materials were made from genetically related animals (perhaps from the same herd).[25]

In 2020, it was reported that the species of several of the animals used to provide parchment for the Dead Sea Scrolls could be identified, and the relationship between skins obtained from the same animal inferred.[26] The breakthrough was made possible by the use of whole genome sequencing.

References

Notes

- Thomson, Roy (2007). Conservation of Leather and Related Materials (Repr ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-4881-3.

- Johnston, Edward (1906). Writing & Illuminating, & Lettering. London: John Hogg.

- Cains, Anthony (1994). "The surface examination of skin: a binder's note on the identification of animal species used in the making of parchment". In O'Mahony, Felicity (ed.). The Book of Kells: proceedings of a conference at Trinity College Dublin, 6–9 September 1992. Aldershot: Scolar Press. pp. 172–4. ISBN 0-85967-967-5.

- William Horman, Vulgaria (1519), fol. 80v; cited in Ustick 1936, p. 440.

- Ham 5.1 M

- Ustick 1936, p. 440.

- Stokes and Almagno 2001, p. 114.

- Clemens and Graham 2007, pp. 9–10.

- "parchment (writing material)". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-07-05. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- Green, Peter (1990). Alexander to Actium: the historical evolution of the Hellenistic age. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 168. ISBN 0520056116.

- Meir Bar-Ilan. "Parchment". Bar-Ilan University – Faculty Members Homepages. Archived from the original on 2005-04-22. Retrieved 2005-04-24.

- "The History Of Vellum And Parchment | The New Antiquarian | The Blog of The Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America". www.abaa.org. Archived from the original on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 2018-03-06.

- David Diringer, The Book before Printing: Ancient, Medieval and Oriental, Dover Publications, New York 1982, p. 172.

- Maimonides, Hilkhoth Tefillin 1:3.

- Quoted in David McKitterick, Print, Manuscript, and the Search for Order Cambridge University Press, 2003

- "Clasps, Furniture, and Other Closures". Hand Bookindings. Princeton University Library. 2004. Archived from the original on 2011-12-08. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- For examples of current artists using parchment see:

- Contemporary Illumination Archived 2005-08-29 at the Wayback Machine

- The St. John's Bible Archived 2017-12-23 at the Wayback Machine,

- More Contemporary Illumination Archived 2005-06-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- Parchmenter Archived 2009-02-20 at the Wayback Machine.

- Kare Parchment.

- Santos, F.J.; Gomez-Martinez, I.; Garcia-Leon, M. "Radiocarbon dating of medieval manuscripts from the University of Seville" (PDF). Digital.csic.es. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-03-23.

- Stolte, D. (2011). "UA experts determine age of book 'nobody can read'". www.uanews.org. Archived from the original on 2015-04-04. Retrieved 2015-03-23.

- Reed, Ronald (1972). Ancient Skins Parchments and Leathers. London: Seminar Press.

- Reed, 1975.

- See for example recipes in the Secretum Philosophorum

- Di Curci 2003.

- "Information Leaflet by Vaad Mishmereth Staam" (PDF). CC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2008.

- Stinson 2009.

- Anava, Neuhof & Gingold 2020.

Bibliography

- Anava, Sarit; Neuhof, Moran; Gingold, Moran (2020). "Illuminating Genetic Mysteries of the Dead Sea Scrolls". Cell. 181: 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.046.

- Clemens, Raymond; Graham, Timothy (2007). Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-3863-9.

- Murray, Fiona (2003). "Parchment craft". Australian Paper Crafts. 23: 10–13.

- Reed, Ronald (1975). The Nature and Making of Parchment. Leeds: Elmete Press. ISBN 0950336726.

- Roberts, Colin H.; Skeat, T. C. (1983), The Birth of the Codex, London: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-726024-1

- Stinson, Timothy L. (2009). "Knowledge of the flesh: using DNA analysis to unlock bibliographical secrets of medieval parchment". Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America. 103 (4): 435–453. doi:10.1086/pbsa.103.4.24293890. JSTOR 24293890. PMID 20607890.

- Stokes, Roy Bishop; Almagno, R. Stephen (2001). Esdaile's Manual of Bibliography (6th ed.). London: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810839229.

- Ustick, W. Lee (1936). "'Parchment' and 'vellum'". The Library. 4th ser. 16 (4): 439–43. doi:10.1093/library/s4-XVI.4.439.

Further reading

- Bar-Ilan, Meir (1997). "Parchment". In Meyers, Eric M. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East. 4. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 247–248. ISBN 0195112180.

- Dougherty, Raymond P. (1928). "Writing upon parchment and papyrus among the Babylonians and the Assyrians". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 48: 109–135. doi:10.2307/593130. JSTOR 593130.

- Eisenlohr, Erika (1996), "Die Kunst, Pergament zu machen", in Lindgren, Uta (ed.), Europäische Technik im Mittelalter: 800 bis 1400: Tradition und Innovation (4th ed.), Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, pp. 429–432, ISBN 3-7861-1748-9

- Hunter, Dard (1978) [1947]. Papermaking: the history and technique of an ancient craft. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486236193.

- Reed, Ronald (1972). Ancient Skins, Parchments, and Leathers. London: Seminar Press. ISBN 0-12-903550-5.

- Ryder, Michael L. (1964). "Parchment: its history, manufacture and composition". Journal of the Society of Archivists. 2 (9): 391–399. doi:10.1080/00379816009513778.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parchments. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Parchment. |

- di Curci, Meliora (2003). "The History and Technology of Parchment Making". Lochac College of Scribes.

- Preservation of 18th Century Parchment | "From the Stacks" at New-York Historical Society

- On-line demonstration of the preparation of vellum (in French), Bibliothèque nationale de France – Text in French, but mostly visual

.jpg)