No Religious Test Clause

The No Religious Test Clause of the United States Constitution is a clause within Article VI, Clause 3. By its plain terms, no federal officeholder or employee can be required to adhere to or accept any particular religion or doctrine as a prerequisite to holding a federal office or a federal government job. It immediately follows a clause requiring all federal office holders to take an oath or affirmation to support the Constitution. This clause contains the only explicit reference to religion in the original seven articles of the U.S. Constitution.

| Constitutional law of the United States |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

| Principles |

| Government structure |

| Individual rights |

|

| Theory |

The ban on religious tests contained in this clause protects only federal officeholders and employees. It does not apply to the states, many of which imposed religious tests at the time of the nation's founding. State tests limited public offices to Christians or, in some states, only to Protestants. The national government, on the other hand, could not impose any religious test whatsoever. National offices would be open to everyone. No federal official has ever been subjected to a formal religious test for holding office.[1]

This clause is cited by advocates of separation of church and state as an example of the "original intent" of the Framers of the Constitution to avoid any entanglement between church and state, or involving the government in any way as a determiner of religious beliefs or practices. This is significant because this clause represents the words of the original Framers, even prior to the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

Text

... ; but no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.

Background

A variety of Test Acts were instituted in England in the 17th and 18th centuries. Their main purpose was to exclude anyone not a member of the Church of England—the official state religion—from holding government office, notably Catholics and "nonconforming" Protestants. Government officials were required to swear oaths, such as the Oath of Supremacy, that the monarch of England was the head of the Church and that they possessed no other foreign loyalties, such as to the pope. Later acts required officials to disavow transubstantiation and the veneration of saints. Such laws were common throughout Europe, where numerous countries had a state religion.

Many colonists of the Thirteen Colonies had left England in part in search of a place where they could practice their own religion. In many cases the colonial governments they set up established an official religion, requiring residents to adhere to the beliefs of the founding sect.[2] With the royal government's religious favoritism fresh in their memory, the Founders sought to prevent the return of the Test Acts by adding this clause to the Constitution. Specifically, Charles Pinckney, delegate from South Carolina – where a Protestant denomination was the established state religion – introduced the clause to Article VI, and it passed with little opposition.[3][4]

Forced oaths

The Supreme Court has interpreted this provision broadly, saying that any required oath to serve anything other than the Constitution is invalid. In the case of Ex parte Garland, the Court overturned a loyalty oath that the government had tried to apply to pardoned Confederate officials. As the officials had already received full presidential pardons (negating an argument based on their potential status as criminals), the Court ruled that forcing officials and judges to swear loyalty oaths was unconstitutional.

State law

Earlier in U.S. history, the doctrine of states' rights allowed individual states complete discretion regarding the inclusion of a religious test in their state constitutions. In 1961 such religious tests by the states were deemed to be unconstitutional by the extension of the First Amendment provisions to the states (via the incorporation of the 14th Amendment). In the 1961 case Torcaso v. Watkins, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled that such language in state constitutions was in violation of the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution.[5] Citing the Supreme Court's interpretation of the Establishment Clause in Everson v. Board of Education and linking it to Torcaso v. Watkins, Justice Hugo Black stated for the Court:

We repeat and again reaffirm that neither a State nor the Federal Government can constitutionally force a person "to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion." Neither can constitutionally pass laws or impose requirements which aid all religions as against non-believers, and neither can aid those religions based on a belief in the existence of God as against those religions founded on different beliefs.

The Supreme Court did not rule on the applicability of Article VI, stating that "Because we are reversing the judgment on other grounds, we find it unnecessary to consider appellant's contention that this provision applies to state as well as federal offices."

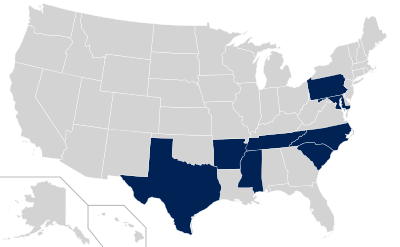

Eight states still do include language in their constitutions either requiring state officeholders to have particular religious beliefs or specifically protecting those who do. However, the requirements are unenforceable because of the 1961 Supreme Court decision. The states are:

- Arkansas (Article 19 Section 1)

- Maryland (Declaration of Rights, Article 37)

- Mississippi (Article 14, Section 265)

- North Carolina (Article 6 Section 8)

- Pennsylvania (Article 1 Section 4)

Specifically protects officeholders with religious belief but is silent on whether those without such beliefs are also protected.[6] The required beliefs include belief in a Supreme Being, and belief in a future state of rewards and punishments. - South Carolina (Article 17 Section 4)

- Tennessee (Article 9 Section 2)

- Texas (Article 1 Section 4)

Some of these same states also specify that the oath of office include the words "so help me God". In some cases, these beliefs (or oaths) were historically required also of jurors, witnesses in court, notaries public, and state employees. In the 1997 case of Silverman v. Campbell,[7] the South Carolina Supreme Court ruled that the state constitution requiring an oath to God for employment in the public sector violated Article VI of the federal constitution, as well as the First and Fourteenth Amendments, and therefore could not be enforced.[8]

References

- Bradley, Gerard V. "Essays on Article VI: Religious Test". The Heritage Guide to The Constitution. The Heritage Foundation.

- Davis, Kenneth C. (October 2010). "America's True History of Religious Tolerance". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- Drawn from original source: Charles C. Haynes (1991). "overview: history of religious liberty in America". A Framework for Civic Education. Council for the Advancement of Citizenship and the Center for Civic Education. Archived from the original on 2013-01-15. Retrieved 2012-10-13.

- Drawn from original source: "The Individual Liberties within the Body of the Constitution: A Symposium: The No Religious Test Clause and the Constitution of Religious Liberty: A Machine That Has Gone of Itself." Case Western Reserve Law Review 37: 674–747. Dreisbach, Daniel L. 1999. "The Bill of Rights: Almost an Afterthought?". ABC-CLIO. 2011.

- "Torcaso v. Watkins". Berkeley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Georgetown University. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- "Religious discrimination in state constitutions". Religioustolerance.org. Retrieved 2008-09-06.

- 486 SE.2d 1, 326 S.C. 208 (1997)

- 486 SE.2d 1, 326 S.C. 208 (1997)