History of Connecticut

The U.S. state of Connecticut began as three distinct settlements of Puritans from Massachusetts and England; they combined under a single royal charter in 1663. Known as the "land of steady habits" for its political, social and religious conservatism, the colony prospered from the trade and farming of its ethnic English Protestant population. The Congregational and Unitarian churches became prominent here. Connecticut played an active role in the American Revolution, and became a bastion of the conservative, business-oriented, Constitutionalism Federalist Party.

The word "Connecticut" is a French corruption of the Algonkian word quinetucket, which means "beside the long, tidal river".[1][2]

Reverend Thomas Hooker and the Rev. Samuel Stone led a group of about 100 who, in 1636, founded the settlement of Hartford, named for Stone's place of birth: Hertford, in England. Called today "the Father of Connecticut," Thomas Hooker was a towering figure in the early development of colonial New England. He was one of the great preachers of his time, an erudite writer on Christian subjects, the first minister of Cambridge, Massachusetts, one of the first settlers and founders of both the city of Hartford and the state of Connecticut, and cited by many as the inspiration for the "Fundamental Orders of Connecticut," cited by some as the world's first written democratic constitution that established a representative government.

The state took a leading role in the industrial revolution of the United States, with its many factories establishing a worldwide reputation for advanced machinery. The educational and intellectual establishment was strongly led by Yale College, by scholars such as Noah Webster and by writers such as Mark Twain, who lived in Connecticut after establishing his association with the Mississippi River. Many Yankees left the farms to migrate west to New York and the Midwest in the early nineteenth century. Meanwhile, the heavy demand for labor in the nineteenth century attracted Irish, English and Italian immigrants, among many others, to the medium and small industrial cities. In the early 20th century, immigrants came from eastern and southern Europe. While the state produced few nationally prominent political leaders, Connecticut has usually been a swing state closely balanced between the parties. In the 21st century, the state is known for production of jet engines, nuclear submarines, and advanced pharmaceuticals.

Colonies in Connecticut

Various Algonquian tribes long inhabited the area prior to European settlement. The Dutch were the first Europeans in Connecticut. In 1614 Adriaen Block explored the coast of Long Island Sound, and sailed up the Connecticut River at least as far as the confluence of the Park River, site of modern Hartford. By 1623, the new Dutch West India Company regularly traded for furs there and ten years later they fortified it for protection from the Pequot Indians, as well as from the expanding English colonies. The site was named "House of Hope" (also identified as "Fort Hoop", "Good Hope" and "Hope"), but encroaching English colonists made them agree to withdraw in the 1650 Treaty of Hartford. By 1654 they were gone, before the English took over New Netherland in 1664.

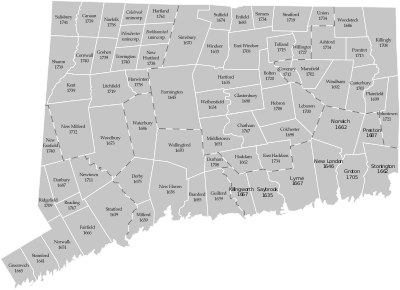

The first English colonists came from the Bay Colony and Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts. Original Connecticut Colony settlements were at Windsor in 1633; at Wethersfield in 1634; and in 1636, at Hartford and Springfield, (the latter was administered by Connecticut until defecting in 1640.) [3] The Hartford settlement was led by Reverend Thomas Hooker.

In 1631, the Earl of Warwick granted a patent to a company of investors headed by William Fiennes, 1st Viscount Saye and Sele, and Robert Greville, 2nd Baron Brooke. They funded the establishment of the Saybrook Colony (named for the two lords) at the mouth of the Connecticut River, where Fort Saybrook, was erected in 1636. Another Puritan group left Massachusetts and started the New Haven Colony farther west on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in 1637. The Massachusetts colonies did not seek to govern their progeny in Connecticut and Rhode Island. Communication and travel were too difficult, and it was also convenient to have a place for nonconformists to go.

The English settlement and trading post at Windsor especially threatened the Dutch trade, since it was upriver and more accessible to Native people from the interior. That fall and winter the Dutch sent a party upriver as far as modern Springfield, Massachusetts spreading gifts to convince the indigenous inhabitants in the area to bring their trade to the Dutch post at Hartford. Unfortunately, they also spread smallpox and, by the end of the 1633–34 winter, the Native population of the entire valley was reduced from over 8,000 to less than 2,000. Europeans took advantage of this decimation by further settling the fertile valley.

The Pequot War

The Pequot War was the first serious armed conflict between the indigenous peoples and the European settlers in New England. The ravages of disease, coupled with trade pressures, invited the Pequots to tighten their hold on the river tribes. Additional incidents began to involve the colonists in the area in 1635, and next spring their raid on Wethersfield prompted the three towns to meet. Following the raid on Wethersfield, the war climaxed when 300 Pequot men, women, and children were burned out of their village, in Mystic.[4]

On May 1, 1637, leaders of Connecticut Colony's river towns each sent delegates to the first General Court held at the meeting house in Hartford. This was the start of self-government in Connecticut. They pooled their militia under the command of John Mason of Windsor, and declared war on the Pequots. When the war was over, the Pequots had been destroyed as a tribe. In the Treaty of Hartford in 1638, the various New England colonies and their Native allies divided the lands of the Pequots, along with surviving Pequots, taken captive by the various tribes, amongst themselves.

New Haven Colony, 1638-1664

In 1637 a group of London merchants and their families, disgusted with the high Church Anglicanism around them, moved to Boston with the intention of creating a new settlement.[5] The leaders were John Davenport, a Puritan minister, and Theophilus Eaton, a wealthy merchant who brought £3000 to the venture. They understood theology, business and trade, but had no farming experience. The good port locations in Massachusetts had been taken, but with the removal of the Pequot Indians, there were good harbors available on Long Island Sound. Eaton found a good location in spring 1638 which he named New Haven. The site seemed ideal for trade, with a good port lying between Boston and the Dutch city of New Amsterdam (New York City), and good access to the furs of the Connecticut River valley settlements of Hartford and Springfield. The settlers had no official charter or permissions, and did not purchase any land rights from the local Indians. Legally, they were squatters.[6] Minister Davenport was an Oxford-educated intellectual, and he set up a grammar school and wanted to establish a college, but failed to do so. The leaders attempted numerous merchandising enterprises, but they all failed. Much of their money went into a great ship sent to London in 1646, with £5000 in cargo of grain and beaver pelts. It never arrived.[7]

The history of the New Haven colony was a series of disappointments and failures. The most serious problem was that it never had a legal title to exist, that is a charter, though the same can be said for Connecticut for most of this period. The larger, stronger colony of Connecticut to the north did obtain Royal charter in 1662, and it was aggressive in using its military superiority to force a takeover. New Haven had other weaknesses as well. The leaders were businessmen and traders, but they were never able to build up a large or profitable trade, because their agricultural base was poor, and the location was isolated. Farming on the poor soil of the colony was a formula for poverty and discouragement. New Haven's political system was confined to church members only, and the refusal to widen it alienated many people. More and more it was realized that the New Haven colony was a hopeless endeavor. Oliver Cromwell recommended that they all migrate to Ireland, or to Spanish territories that he planned to conquer. After Cromwell died three regicides who (with Cromwell) had voted to execute King Charles I escaped from England and hid in New Haven. The colony had a very negative standing in London, and plans were afoot to merge it with New York. But the Puritans of New Haven were too conservative, and too wedded to their new land to leave or join the Anglicans in New York. One by one in 1662-64 the towns joined Connecticut until only three were left and they too submitted to the Connecticut Colony in 1664. They gave up their theocracy but became well integrated, with numerous important leaders and (after Yale opened in 1701), influential academics.[8]

Under the Fundamental Orders

The three River Towns, Wethersfield, Windsor and Hartford, had created a general government when faced with the demands of a war. On January 14, 1639, freemen from these three settlements ratified the "Fundamental Orders of Connecticut" in what John Fiske called "the first written constitution known to history that created a government. It marked the beginnings of American democracy, of which Thomas Hooker deserves more than any other man to be called the father. The government of the United States today is in lineal descent more nearly related to that of Connecticut than to that of any of the other thirteen colonies."[9] Rapid growth and expansion grew under this new regime.[10]

On April 22, 1662, the Connecticut Colony succeeded in gaining a Royal Charter that embodied and confirmed the self-government that they had created with the Fundamental Orders. The only significant change was that it called for a single Connecticut government with a southern limit at the Long Island Sound, including today Suffolk County on Long Island, and a western limit of the Pacific Ocean, which meant that this charter was still in conflict with the New Netherland colony.

Indian pressures were relieved for some time by success in the ferocious Pequot War. While the Pequots themselves gathered again along the Thames River, other tribes, especially the Mohegans, grew more powerful, though they had a rivalry with the Narragansetts located in Western Rhode Island and Eastern Connecticut, and this rivalry shaped in a large part diplomatic matters between both Indian tribes and colonial affairs. King Philip's War (1675–1676) spilled over from Plymouth Colony; Connecticut provided men and supplies. Connecticut's contribution to the war also included the large number of Indian allies they brought into the war, including the Mohegans, led by Uncas and the Pequots, of which a small population had reformed from runaway slaves taken at the end of the Pequot War. The participation of Native Allies is in a large part responsible for the Colonial Victory, and this participation was largely due to Connecticut's involvement, as they generally had the best relationships with their local Native tribes, in particular the Mohegans. [11] The colonists had seen some Indians as a potential deadly threat, and mobilized during both the Pequot war and King Philip's War to eliminate them. More than three-fourths of all adult men provided some form of military service.[12] Given the numbers of Native troops fighting with the colonists, along with estimates of Native populations, it is likely that an even larger proportion of Native troops served with Connecticut.

The Dominion of New England

In 1686, Sir Edmund Andros was commissioned as the Royal Governor of the Dominion of New England. Andros maintained that his commission superseded Connecticut's 1662 charter. At first, Connecticut ignored this situation. But in late October 1687, Andros arrived with troops and naval support. Governor Robert Treat had no choice but to convene the assembly. Andros met with the governor and General Court on the evening of October 31, 1687.

Governor Andros praised their industry and government, but after he read them his commission, he demanded their charter. As they placed it on the table, people blew out all the candles. When the light was restored, the charter was missing. According to legend, it was hidden in the Charter Oak. Sir Edmund named four members to his Council for the Government of New England and proceeded to his capital at Boston.

Since Andros viewed New York and Massachusetts as the important parts of his Dominion, he mostly ignored Connecticut. Aside from some taxes demanded and sent to Boston, Connecticut also mostly ignored the new government. When word arrived that the Glorious Revolution had placed William and Mary on the throne, the citizens of Boston arrested Andros and sent him back to England in chains. The Connecticut court met and voted on May 9, 1689 to restore the old charter. They also reelected Robert Treat as governor each year until 1698.

Territorial disputes

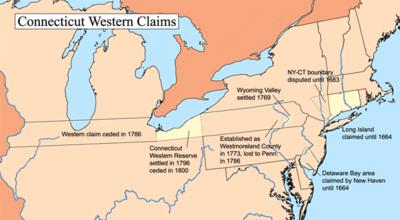

According to the 1650 Treaty of Hartford with the Dutch, the western boundary of Connecticut ran north from the west side of Greenwich Bay "provided the said line come not within 10 miles (16 km) of Hudson River." On the other hand, Connecticut's original charter in 1662 granted it all the land to the "South Sea" (i.e. the Pacific Ocean).

- ALL that parte of our dominions in Newe England in America bounded on the East by Norrogancett River, commonly called Norrogancett Bay, where the said River falleth into the Sea, and on the North by the lyne of the Massachusetts Plantacon, and on the south by the Sea, and in longitude as the lyne of the Massachusetts Colony, runinge from East to West, (that is to say) from the Said Norrogancett Bay on the East to the South Sea on the West parte, with the Islands thervnto adioyneinge, Together with all firme lands ... TO HAVE AND TO HOLD ... for ever....

Dispute with New York

Needless to say, this brought it into territorial conflict with those states which then lay between Connecticut and the Pacific. A patent issued on March 12, 1664, granted the Duke of York (later James II & VII) "all the land from the west side of Connecticut River to the east side of Delaware Bay." In October 1664, Connecticut and New York agreed to grant Long Island to New York, and establish the boundary between Connecticut and New York as a line from the Mamaroneck River "north-northwest to the line of the Massachusetts", crossing the Hudson River near Peekskill and the boundary of Massachusetts near the northwest corner of the current Ulster County, New York. This agreement was never really accepted, however, and boundary disputes continued. The Governor of New York issued arrest warrants for residents of Greenwich, Rye, and Stamford, and founded a settlement north of Tarrytown in what Connecticut considered part of its territory in May 1682. In 1675, with King Philip's War posing significant pressure on Connecticut, New York attempted to land a force at Saybrook, in an attempt to take hold of the Connecticut River, and to assert their claim over all lands west of the Connecticut River itself, though these forces were repelled by Connecticut Colonial forces without a fight. Finally, on November 28, 1683, the states negotiated a new agreement establishing the border as 20 miles (32 km) east of the Hudson River, north to Massachusetts. In recognition of the wishes of the residents, the 61,660 acres (249.5 km2) east of the Byram River making up the Connecticut Panhandle were granted to Connecticut. In exchange, Rye was granted to New York, along with a 1.81-mile-wide (2.91 km) strip of land running north from Ridgefield to Massachusetts alongside Dutchess, Putnam, and Westchester Counties, New York, known as the "Oblong".

Dispute with Pennsylvania

In the 1750s, the western frontier remained on the other side of New York. In 1754 the Susquehannah Company of Windham, Connecticut obtained from a group of Native Americans a deed to a tract of land along the Susquehanna River which covered about one-third of present-day Pennsylvania. This venture met with the disapproval of not only Pennsylvania, but also of many in Connecticut including the Deputy Governor, who opposed Governor Jonathan Trumbull's support for the company, fearing that pressing these claims would endanger the charter of the colony. In 1769, Wilkes-Barre was founded by John Durkee and a group of 240 Connecticut settlers. The British government finally ruled "that no Connecticut settlements could be made until the royal pleasure was known". In 1773 the issue was settled in favor of Connecticut and Westmoreland, Connecticut was established as a town and later a county.

Pennsylvania did not accede to the ruling, however, and open warfare broke out between them and Connecticut, ending with an attack in July 1778, which killed approximately 150 of the settlers and forced thousands to flee. While they periodically attempted to regain their land, they were continuously repulsed, until, in December 1783, a commission ruled in favor of Pennsylvania. After complex litigation, in 1786, Connecticut dropped its claims by a deed of cession to Congress, in exchange for freedom for war debt and confirmation of the rights to land further west in present-day Ohio, which became known as the Western Reserve. Pennsylvania granted the individual settlers from Connecticut the titles to their land claims. Although the region had been called Westmoreland County, Connecticut, it has no relationship with the current Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania.

The Western Reserve, which Connecticut received in recompense for giving up all claims to any Pennsylvania land in 1786, constituted a strip of land in what is currently northeast Ohio, 120 miles (190 km) wide from east to west bordering Lake Erie and Pennsylvania. Connecticut owned this territory until selling it to the Connecticut Land Company in 1795 for $1,200,000, which resold parcels of land to settlers. In 1796, the first settlers, led by Moses Cleaveland, began a community which was to become Cleveland, Ohio; in a short time, the area became known as "New Connecticut".

An area 25 miles (40 km) wide at the western end of the Western Reserve, set aside by Connecticut in 1792 to compensate those from Danbury, New Haven, Fairfield, Norwalk, and New London who had suffered heavy losses when they were burnt out by fires set by British raids during the War of Independence, became known as the Firelands. By this time, however, most of those granted the relief by the state were either dead or too old to actually move there. The Firelands now constitutes Erie and Huron Counties, as well as part of Ashland County, Ohio.

Conservatism

Connecticut was the land of steady habits, with a conservative elite that dominated colonial affairs.[13] The forces of liberalism and democracy emerged slowly, encouraged by the entrepreneurship of the business community, and the new religious freedom stimulated by the First Great Awakening.[14]

Yale College was founded in 1701 to educate ministers and civil leaders. After moving about it settled in New Haven. Just as Yale College dominated Connecticut's intellectual life, the Congregational church dominated religion in the colony. It was officially established until 1818, and the residents of each town were all required to attend Sunday services and to pay taxes to support it (or else prove they supported a Baptist or some other Protestant church).[15]

Centralizing forces made the Congregational church even more powerful and more conservative. The Saybrook Platform was a new constitution for the Congregational church in 1708. Religious and civic leaders in Connecticut around 1700 were distressed by the colony-wide decline in personal religious piety and in church discipline. The colonial legislature sponsored a meeting in Saybrook comprising eight Yale trustees and other colonial worthies. It drafted articles which rejected extreme localism or Congregationalism that had been inherited from England, and replaced it with a system similar to what the Presbyterians had. The Congregational church was now to be led by local ministerial associations and consociations comprising ministers and lay leaders from a specific geographical area. Instead of the congregation from each local church selecting its minister, the associations now had the responsibility to examine candidates for the ministry, and to oversee a behavior of the ministers. The consociations (where laymen were powerless) could impose discipline on specific churches and judge disputes that arose. The result was a centralization of power that bothered many local church activists. However, the official associations responded by disfellowshipping churches that refuse to comply. The system survived to the mid-nineteenth century, well after Congregationalism was officially this disestablished in the state of Connecticut.[16][17]

The Platform marked a conservative counter-revolution against a non-conformist tide which had begun with the Halfway Covenant and would later culminate in the Great Awakening in the 1740s. The Great Awakening bitterly divided Congregationalists between the "New Lights" who welcomed the revivals, and the "Old Lights" who used governmental authority to suppress revivals.

The legislature, controlled by the Old Lights, in 1742 passed an "Act for regulating abuses and correcting disorder in ecclesiastical affairs" that sharply restricted ministers from leading revivals. Another law was passed to prevent the opening of a New Light seminary. Numerous New Light evangelicals were imprisoned or fined. The New Lights responded by their own political organization, fighting it out town by town. Although the religious issues decline somewhat after 1748, the New Light versus Old Light factionalism spilled into other issues, such as disputes over currency, and Imperial issues. However, the divisions involved did not play a role in the coming of the American Revolution, which both sides supported.[18]

The career of a soldier was not held in high prestige in Connecticut. However, London demanded some assistance in its numerous wars against France, so the colony sent soldiers into Canada, 1709–1711, during Queen Anne's War. Silesky argues that Connecticut followed the same procedure for the rest of the century. Elites in control of the government used cash bounties to encourage poor men to volunteer to serve temporarily.[19]

Governor Jonathan Trumbull was elected every year from 1769 to 1784. Connecticut's political system was practically unaffected by the Revolution.

The American Revolution (1775–1789)

The conservative elite strongly supported the American revolution, and the forces of Loyalism were weak. Connecticut designated four delegates to the Second Continental Congress who would sign the Declaration of Independence: Samuel Huntington, Roger Sherman, William Williams, and Oliver Wolcott.[20]

In 1775, in the wake of the clashes between British regulars and Massachusetts militia at Lexington and Concord, Connecticut's legislature authorized the outfitting of six new regiments, with some 1,200 Connecticut troops on hand at the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775.[21]

Getting word in 1777 of Continental Army supplies in Danbury, the British landed an expeditionary force of some 2,000 troops in Westport, who marched to Danbury and destroyed much of the depot along with homes in Danbury. On the return march, Continental Army troops and militia led by General David Wooster and General Benedict Arnold engaged the British at Ridgefield in 1777, which would deter future strategic landing attempts by the British for the remainder of the war.

For the winter of 1778–79, General George Washington decided to split the Continental Army into three divisions encircling New York City, where British General Sir Henry Clinton had taken up winter quarters.[22] Major General Israel Putnam chose Redding as the winter encampment quarters for some 3,000 regulars and militia under his command. The Redding encampment allowed Putnam's soldiers to guard the replenished supply depot in Danbury and support any operations along Long Island Sound and the Hudson River Valley.[23] Some of the men were veterans of the winter encampment at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania the previous winter. Soldiers at the Redding camp endured supply shortages, cold temperatures and significant snow, with some historians dubbing the encampment "Connecticut's Valley Forge."[24]

The state was also the launching site for a number of raids against Long Island orchestrated by Samuel Holden Parsons and Benjamin Tallmadge, and provided men and material for the war effort, especially to Washington's army outside New York City. General William Tryon raided the Connecticut coast in July 1779, focusing on New Haven, Norwalk, and Fairfield. The French General the Comte de Rochambeau celebrated the first Catholic Mass in Connecticut at Lebanon in summer 1781 while marching through the state from Rhode Island to rendezvous with General George Washington in Dobbs Ferry, New York. Rochambeau and Washington also planned in Wethersfield the Battle of Yorktown and the British surrender. New London and Groton Heights were raided in September 1781 by Connecticut native and turncoat Benedict Arnold.

Early National Period (1789–1818)

New England was the stronghold of the Federalist party. One historian explains how well organized it was in Connecticut:

- It was only necessary to perfect the working methods of the organized body of office-holders who made up the nucleus of the party. There were the state officers, the assistants, and a large majority of the Assembly. In every county there was a sheriff with his deputies. All of the state, county, and town judges were potential and generally active workers. Every town had several justices of the peace, school directors and, in Federalist towns, all the town officers who were ready to carry on the party's work. Every parish had a "standing agent," whose anathemas were said to convince at least ten voting deacons. Militia officers, state's attorneys, lawyers, professors and schoolteachers were in the van of this "conscript army." In all, about a thousand or eleven hundred dependent officer-holders were described as the inner ring which could always be depended upon for their own and enough more votes within their control to decide an election. This was the Federalist machine.[25]

Given the power of the Federalists, the Republicans had to work harder to win. In 1806, the state leadership sent town leaders instructions for the forthcoming elections. Every town manager was told by state leaders "to appoint a district manager in each district or section of his town, obtaining from each an assurance that he will faithfully do his duty." Then, the town manager was instructed to compile lists and total up the number of taxpayers, the number of eligible voters, how many were "decided republicans," "decided federalists," or "doubtful," and finally to count the number of supporters who were not currently eligible to vote but who might qualify (by age or taxes) at the next election. These highly detailed returns were to be sent to the county manager. They, in turn, were to compile county-wide statistics and send it on to the state manager. Using the newly compiled lists of potential voters, the managers were told to get all the eligibles to the town meetings, and help the young men qualify to vote. At the annual official town meeting, the managers were told to, "notice what republicans are present, and see that each stays and votes till the whole business is ended. And each District-Manager shall report to the Town-Manager the names of all republicans absent, and the cause of absence, if known to him." Of utmost importance, the managers had to nominate candidates for local elections, and to print and distribute the party ticket. The state manager was responsible for supplying party newspapers to each town for distribution by town and district managers.[26] This highly coordinated "get-out-the-vote" drive would be familiar to modern political campaigners, but was the first of its kind in world history.

Connecticut prospered during the era, as the seaports were busy and the first textile factories were built. The American Embargo and the British blockade during the War of 1812 severely hurt the export business, and bolstered the Federalists who strongly opposed the Embargo and the War of 1812.[27] The cutoff of imports from Britain did stimulate the rapid growth of factories to replace the textiles and machinery. Eli Whitney of New Haven was a leader of the engineers and inventors who made the state a world leader in machine tools and industrial technology generally. The state was known for its political conservatism, typified by its Federalist party and the Yale College of Timothy Dwight. The foremost intellectuals were Dwight and Noah Webster, who compiled his great dictionary in New Haven. Religious tensions polarized the state, as the established Congregational Church, in alliance with the Federalists, tried to maintain its grip on power. The failure of the Hartford Convention in 1814 wounded the Federalists, who were finally upended by the Republicans in 1817.

Modernization and industry

Up until this time, Connecticut had adhered to the 1662 Charter, and with the independence of the American colonies over forty years prior, much of what the Charter stood for was no longer relevant. In 1818, a new constitution was adopted that was the first piece of written legislation to separate church and state in Connecticut, and give equality all religions. Gubernatorial powers were also expanded as well as increased independence for courts by allowing their judges to serve life terms.

Connecticut started off with the raw materials of abundant running water and navigable waterways, and using the Yankee work ethic quickly became an industrial leader. Between the birth of the U.S. patent system in 1790 and 1930, Connecticut had more patents issued per capita than any other state; in the 1800s, when the U.S. as a whole was issued one patent per three thousand population, Connecticut inventors were issued one patent for every 700–1000 residents. Connecticut's first recorded invention was a lapidary machine, by Abel Buell of Killingworth, in 1765.

Abolition and integration

Starting in the 1830s, and accelerating when Connecticut abolished slavery entirely in 1848, African Americans from in- and out-of-state began relocating to urban centers for employment and opportunity, forming new neighborhoods such as Bridgeport's Little Liberia.[28]

In 1832, Quaker schoolteacher Prudence Crandall created the first integrated schoolhouse in the United States by admitting Sarah Harris, the daughter of a free African-American farmer in the local community, to her Canterbury Female Boarding School in Canterbury. Many prominent townspeople objected and pressured to have Harris dismissed from the school, but Crandall refused. Families of the current students removed their daughters. Consequently, Crandall ceased teaching white girls altogether and opened up her school strictly to African American girls.[29] In 1995, the Connecticut General Assembly designated Prudence Crandall as the state's official heroine.[30]

Civil War era

Connecticut manufacturers played a leading role in supplying the Union forces with rifles, cannon, ammunition, and military materiel during the Civil War. The state furnished 55,000 men. They were formed into thirty full regiments of infantry, including two in the U.S. Colored Troops made up of black men and white officers. Two regiments of heavy artillery served as infantry toward the end of the war. Connecticut also supplied three batteries of light artillery and one regiment of cavalry. The Navy attracted 250 officers and 2100 men. A number of Connecticut men became Union generals; Gideon Welles was a moderate whom Lincoln made Secretary of the Navy. Casualties were high: 2088 were killed in combat, 2801 died from disease, and 689 died in Confederate prison camps.[31][32][33]

Politics became red hot during the war. A surge of national unity in 1861 brought thousands flocking to the colors from every town and city. However, as the war became a crusade to end slavery, many Democrats (especially Irish Catholics) pulled back. The Democrats took a peace position and included many Copperheads willing to let the South secede. The intensely fought 1863 election for governor was narrowly won by the Republicans.[34][35]

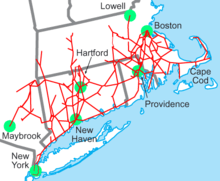

Connecticut's extensive industry, its dense population, its flat terrain, its proximity to metropolitan centers, and the wealth of its residents made it favorable grounds for railroad building, starting in 1839. By 1840, 102 miles of line were in operation, growing to 402 in 1850 and 601 in 1860. The main development after the Civil War was the consolidation of many small local lines into the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad – popularly called "the Consolidated." It sought a monopoly of all transportation, including urban streetcar lines, inter-urban trolleys, and freighters and passenger steamers on Long Island Sound. It was a highly profitable enterprise, until it was bought out in 1903 and suffered serious mismanagement.[36][37]

Twentieth century

Railroads

The New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad, commonly called the New Haven, dominated Connecticut travel after 1872. New York's leading banker, J. P. Morgan, had grown up in Hartford and had a strong interest in the New England economy. Starting in the 1890s Morgan began financing the major New England railroads, and dividing territory so they would not compete. In 1903 he brought in Charles Mellen as president (1903-1913). The goal, richly supported by Morgan's financing, was to purchase and consolidate the main railway lines of New England, merge their operations, lower their costs, electrify the heavily used routes, and modernize the system. With less competition and lower costs, there supposedly would be higher profits. The New Haven purchased 50 smaller companies, including steamship lines, and built a network of light rails (electrified trolleys) that provided inter-urban transportation for all of southern New England. By 1912, the New Haven operated over 2000 miles of track, and 120,000 employees. It practically monopolized traffic in a wide swath from Boston to New York City.

Morgan's quest for monopoly angered reformers during the Progressive Era, most notably Boston lawyer Louis Brandeis, who fought the New Haven for years. Mellen's abrasive tactics alienated public opinion, led to high prices for acquisitions and to costly construction. The accident rate rose when efforts were made to save on maintenance costs. Debt soared from $14 million in 1903 to $242 million in 1913. Also in 1913 it was hit by an anti-trust lawsuit by the federal government and was forced to give up its trolley systems.[38] The advent of automobiles, trucks and buses after 1910 slashed the profits of the New Haven. The line went bankrupt in 1935, was reorganized and reduced in scope, went bankrupt again in 1961, and in 1969 was merged into the Penn Central system, which itself went bankrupt. The remnants of the system are now part of Conrail.[39]

The automotive revolution came much faster than anyone expected, especially the railroads. In 1915 Connecticut had 40,000 automobiles; five years later it had 120,000. There was even faster growth in trucks from 7,000 to 24,000. Local government started upgrading the roads, while entrepreneurs opened dealerships, gasoline stations, repair shops and motels.[40]

Politics

The Republicans dominated state politics after 1896, and had a lock on the legislature where the one-town, one representative rule guaranteed that small rural towns could easily outvote the growing cities. While the Republicans developed factions over personalities, they drew together for elections. The Democrats had more internal dissension over issues, particularly the liberalism of William Jennings Bryan, and they were weakened in general elections. The rural Yankee Democrats battled the urban Irish for control of the state party.[41] Most of the factory workers voted Republican, except the Irish Catholics who were Democrats, so most of the industrial cities voted Republican.

In 1910, the Democrats elected their gubernatorial candidate Simeon Baldwin, a prominent professor at the Yale Law School. As the Republicans split between President William Taft and ex-president Theodore Roosevelt, the Democrats flourished in 1912, carrying the state for president, reelecting Baldwin, sweeping all five congressional districts with ethnic Irish candidates, and taking the state Senate. Only the malapportioned House remained in Republican hands and dominated by rural areas. The state did not participate much in the "progressive era," and the Democrats passed only one piece of liberal legislation; it set up a system of workman's compensation. In 1914, the Republicans pulled themselves together and resumed their control of state politics.[42] J. Henry Roraback was the Republican state leader from 1912 to his death in 1937. His machine, says Lockard, was "efficient, conservative, penurious, and in absolute control."[43] Until the New Deal coalition of the 1930s pulled ethnic voters solidly into the Democratic Party, Roraback was unbeatable with his strong rural organization, funding from the business community, conservative policies, and a hierarchical party organization.[43] Connecticut was the last state (in 1955) to adopt the party primary system, and it was used only if a loser wanted to challenge the choice of the state convention.

World War I

When World War I broke out in 1914, Connecticut's large machine industry received major contracts from British, Canadian, and French interests, as well as the U.S. forces. The largest munitions firms were Remington in Bridgeport, Winchester in New Haven, and Colt in Hartford, as well as the large federal arsenal in Bridgeport.[44]

The state enthusiastically supported the American war effort in 1917–1918, with large purchases of war bonds and a further expansion of war industry, and emphasis on increasing food production in the farms. Thousands of state, local and volunteer groups mobilized for the war effort, and were coordinated by the Connecticut State Council of Defense.[45] Young men were eager to serve whether as volunteers or draftees.[46]

As the war ended the worldwide epidemic of "Spanish Flu" hit the state. Fatalities were high because the state was a travel hub, was heavily urbanized so germs spread faster, and had many recent immigrants in densely settled areas. An estimated 8500-9000 people died, about one percent of the population, and about one-quarter contracted the disease.[47]

Early 20th-century immigrants and ethnicity

Connecticut factories in Bridgeport, New Haven, Waterbury and Hartford were magnets for European immigrants. The largest groups were Italian, and Polish and other Eastern Europeans. They brought Catholic unskilled labor to a historically Protestant state. A significant number of Jewish immigrants also arrived in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[48] Connecticut's population was almost 30% foreign-born by 1910.

These ethnic groups supported the World War (the small numbers of German Americans tried to keep a low profile, encountering hostility and suspicion after the US entered the war.) Ethnic organizations supported an Americanization program for the many recent immigrants.[49] Since transatlantic civilian travel was almost impossible in 1914–20, the flow of new immigrants ended. Recently arrived Italians, Poles and others had to cancel plans to return to their home villages. They moved up as higher-paying jobs opened in the munitions industry. They deepened their roots in American society, and became permanent residents. Instead of identifying with their former ancestral villages, the Italians developed a new pride in being both Americans and Italians. Their children, born in the U.S. and bilingual, flourished economically in the prosperous 1920s.[50][51] The Poles enlisted in large numbers, and generously supported war bond efforts. They were motivated in part by the government's commitment to a process to support an independent Poland, which was achieved after the end of the war.[52]

Nativists in the 1920s opposed the new immigrants as a threat to the state's traditional social and political values. The Ku Klux Klan had a small anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant following in Connecticut in the 1920s, reaching about 15,000 members before its collapse nationwide in 1926 following scandals involving top leaders.[53][54]

Depression and War years

With rising unemployment in urban and rural areas producing disaffection with Republican leaders, Connecticut Democrats saw a chance to return to power. The hero of the movement was Yale English professor Governor Wilbur Lucius Cross (1931–1939), who emulated much of Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal policies by creating new public services, contributing to infrastructure projects, and instituting a minimum wage. The Merritt Parkway was constructed in this period as part of the investment in infrastructure.

In 1938, the state Democratic Party was wracked by controversy, and the Republicans elected Governor Raymond E. Baldwin. Connecticut became a highly competitive, two-party state.

On September 21, 1938, the most destructive storm in New England history struck eastern Connecticut, killing hundreds of people.[55] The eye of the "Long Island Express" hurricane passed just west of New Haven and devastated the Connecticut shoreline between Old Saybrook and Stonington, which lacked the partial protection from the full force of wind and waves provided to the western coast by the barrier of Long Island, New York. The hurricane caused extensive damage to infrastructure, homes and businesses. In New London, a 500-foot sailing ship was driven into a warehouse complex, causing a major fire. Heavy rainfall caused the Connecticut River to flood downtown Hartford and East Hartford. An estimated 50,000 trees fell onto roadways.[56]

The lingering Depression soon gave way to an economic buildup as the United States invested in its defense industry before and during World War II (1941–1945). Roosevelt's call for America to be the Arsenal of Democracy led to remarkable growth in munition-related industries, such as airplane engines, radio, radar, proximity fuzes, rifles, and a thousand other products. Pratt and Whitney made airplane engines, Cheney sewed silk parachutes, and Electric Boat built submarines. This was coupled with traditional manufacturing including guns, ships, uniforms, munitions, and artillery. Connecticut manufactured 4.1 percent of total United States military armaments produced during World War II, ranking ninth among the 48 states.[57] Ken Burns focused on Waterbury's munitions production in his 2007 miniseries The War. Although most munitions production ended in 1945, new industries had resulted from the war, and manufacturing of high tech electronics and airplane parts continued.

Postwar prosperity

Connecticut's suburbs thrived as people moved to newer housing via subsidized highways, while its cities peaked in the 1950s and then began a slow downhill slide as population spread into widely dispersed regions. Connecticut built the first nuclear-powered submarine, the USS Nautilus (SSN-571) and other essential weapons for The Pentagon. At the beginning of the 1960s, the increased job market gave the state the highest per capita income in the nation. The increased standard of living could be seen in the various suburban neighborhoods that began to develop outside major cities. Construction of major highways such as the Connecticut Turnpike, subsidized by federal investment, resulted in former small towns becoming sites for large-scale residential and retail development, a trend that continues to this day, with offices also moving to new locations.

Fairfield County, Connecticut's Gold Coast, was a favorite residence of many executives who worked in New York City. It attracted scores of corporate headquarters from New York, especially in the 1970s, when Connecticut had no state income tax. Connecticut offered ample inexpensive office space, high quality of life to people who did not want to live in New York City, and excellent public schools. The state did not offer any tax incentives for corporations to move their headquarters.[58]

Connecticut industrial workers were very well-paid, many of them in defense industries building nuclear submarines at Electric Boat shipyards, helicopters at Sikorsky, and jet engines at Pratt & Whitney. Labor unions were very powerful after the war, peaking in clout in the early 1970s. Since then the private sector labor unions have dramatically declined in size and influence with the decline in industry as factories closed and jobs were moved out of state and offshore. The public-sector unions, covering teachers, police, and city and state employees, have become more powerful, with influence in the Democratic Party.[59]

Deindustrialization left many industrial centers with empty factories and mills and high unemployment. As wealthier whites moved to suburbs, African American and Latino made up a higher proportion of urban populations, reflecting their later arrival in the Great Migration and immigration, and relative inability to find and move to other jobs. They had gained middle-class status through good-paying industrial jobs and became stranded. African Americans and Latinos inherited againg urban spaces that were no longer a high priority for the state or private industry. By the 1980s crime and urban blight were major issues. The poor conditions were catalysts for militant movements pushing to gentrify ghettos and desegregate the urban school systems, which were surrounded by majority-white suburbs. In 1987, Hartford became the first United States city to elect an African-American woman as mayor, Carrie Saxon Perry.

Politics

Connecticut had very strong state parties, with the GOP led by leaders, such as A. Searle Pinney. John Bailey was the state chairman of the Democrats from 1946 to his death in 1975; he was also the party's national chairman, 1961 until 1968.[60] These party leaders controlled their legislative delegations and ran the state conventions that selected nominees for the top offices. The old WASP element was still a factor in rural Connecticut, but Catholics comprised 44% of the state's population and dominated all of the industrial cities. With the ethnics loyal to the Democratic Party, and labor unions at their peak, the Democratic Party strongly endorsed the New Deal coalition and its liberalism. The Republican Party was mildly liberal, typified by Senator Prescott Bush, a wealthy Yankee whose son and grandson were later each elected as president from their new conservative base in Texas. Connecticut had some difficulty in projecting its identity, with no big-league sports teams and its media markets dominated by outside television stations in New York, Providence, Rhode Island and Springfield, Massachusetts. Bailey's contact with the liberal element that dominated the Democratic Party was Ella Grasso. He promoted her from the legislature, to Secretary of State, to Congress, and finally to the governorship.

Bailey's usual success in dictating the state ticket was upset in 1970, when the Republican gubernatorial candidate, Congressman Thomas Meskill, defeated a lackluster Democrat. More complex was the situation of Senator Thomas Dodd, a Democrat who had been censured by the Senate for his misuse of campaign funds. Dodd lost the Democratic primary, but ran as an independent and split the vote. The result was that liberal Republican Lowell Weicker won the Senate seat with 42% of the vote. Bailey had an easier time in 1974 gaining re-election of Senator Abe Ribicoff. In 1950 Ribicoff was elected as the first Jewish and non-WASP governor in the state's history. Weicker was repeatedly reelected until being narrowly defeated in 1988. He was elected governor in 1990 as an independent.[61][62]

In 1974 Democrats elected as governor Ella T. Grasso, the daughter of Italian immigrants. She was the first woman of any state to be elected governor in her own right. She was reelected in 1978.[63] She faced a major crisis in 1978 when "The Blizzard of 78" dropped 30 inches of snow across the state, crippling highways and making virtually all roads impassible. She "Closed the State" by proclamation, and forbade all use of public roads by businesses and citizens, closing all businesses. Effectively residents were restricted to their homes. This relieved the rescue and cleanup authorities from the need to help the mounting number of stuck cars, and allowed clean-up and emergency services for shut-ins to proceed. The crisis ended on the third day, and Grasso won accolades from all state sectors for her leadership and strength.[64]

The late 20th century

Connecticut's dependence on the defense industry posed an economic challenge at the end of the Cold War. The resulting budget crisis helped elect Lowell Weicker as Governor on a third party ticket in 1990. Despite campaigning against a state income tax, Weicker's remedy to the budget crisis, a state income tax, proved effective in balancing the budget but was politically unpopular. Weicker retired after a single term.

Until the late nineteenth century Connecticut agriculture included tobacco farms. This brought in immigrants from the West Indies, Puerto Rico, and the black South. In the off-season they turned to the cities for temporary apartments, schooling and services, but with the decline of tobacco they moved there permanently.[65]

With newly "reconquered" land, the Pequots initiated plans for the construction of a multimillion-dollar casino complex to be built on reservation land. The Foxwoods Casino was completed in 1992 and the enormous revenue it received made the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation one of the wealthiest in the country. With the newfound money, great educational and cultural initiatives were carried out, including the construction of the Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center. The Mohegan Reservation gained political recognition shortly thereafter and, in 1994, opened another successful casino (Mohegan Sun) near the town of Uncasville. The economic recession that began in 2007 took a heavy toll of receipts, and by 2012 both the Mohegan Sun and Foxwoods were deeply in debt.[66]

Casinos provide an example of the shift in the economy away from manufacturing to entertainment, such as ESPN, financial services, including hedge funds and pharmaceutical firms such as Pfizer.

21st century

In the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, 65 state residents were killed. The vast majority were Fairfield County residents who were working in the World Trade Center. Greenwich lost 12 residents, Stamford and Norwalk each lost nine and Darien lost six.[67] A state memorial was later set up at Sherwood Island State Park in Westport. The New York City skyline can be seen from the park.

A number of political scandals rocked Connecticut in the early 21st century. These included the 2003 removal from office of the mayors of Bridgeport, Joseph P. Ganim on 16 corruption charges,[68] as well as Waterbury mayor Philip A. Giordano, who was charged with 18 counts of sexual abuse of two girls.[69]

In 2004, Governor John G. Rowland resigned during a corruption investigation. Rowland later plead guilty to federal charges, and his successor M. Jodi Rell, focused her administration on reforms in the wake of the Rowland scandal.

In April 2005, Connecticut passed a law which grants all rights of marriage to same-sex couples. However, the law required that such unions be called "civil unions", and that the title of marriage be limited to those unions whose parties are of the opposite sex. The state was the first to pass a law permitting civil unions without a prior court proceeding. In October 2008, the Supreme Court of Connecticut ordered same-sex marriage legalized.

In July 2009, the Connecticut legislature overrode a veto by Governor M. Jodi Rell to pass SustiNet, the first significant public-option health care reform legislation in the nation.[70]

The state's criminal justice system also dealt with the first execution in the state since 1960, the 2005 execution of serial killer Michael Ross and was rocked by the July 2007 home invasion murders in Cheshire. As the accused perpetrators of the Petit murders were out on parole, Governor M. Jodi Rell promised a full investigation into the state's criminal justice policies.[71]

On April 11, 2012 the State House of Representatives voted to end the state's rarely enforced death penalty; the State Senate having previously passed the measure on April 5. Governor Dannel Malloy announced that "when it gets to my desk I will sign it". Eleven inmates were on death row at that time, including the two men convicted of the July 2007 Cheshire, Connecticut, home invasion murders. Controversy exists both in that the legislation is not retroactive and does not commute their sentences[72] and that the repeal is against the majority view of the state's citizens, as 62% are for retaining it.[73]

In 2011 and 2012, Connecticut was hit by three major storms in the space of just over 14 months, with all three causing extensive property damage and electric outages. Hurricane Irene struck Connecticut August 28 with the storm blamed for the deaths of three residents. Damage totaled $235 million, including 20 houses that were destroyed in East Haven.[74] Two months later in late October, the so-called "Halloween nor'easter" dropped extensive snow onto trees in northern Connecticut that still had foliage, resulting in a significant numbers of snapped branches and trunks that damaged property and power lines, with some areas not seeing electricity restored for 11 days.[75] Hurricane Sandy had tropical storm-force winds when it reached Connecticut October 29, 2012, with four deaths blamed on the storm.[76] Sandy's winds drove storm surges into coastal streets, toppled trees and power lines, and cut power to 98 percent of homes and businesses en route to more than $360 million in damage. Some sections along the southeast coast of Connecticut had no power for more than 16 days. [77]

On December 14, 2012, Adam Lanza shot and killed 26 people, including 20 children and 6 staff, at Sandy Hook Elementary School in the Sandy Hook village of Newtown, Connecticut, and then killed himself.[78]

See also

- History of the Connecticut Constitution

- List of newspapers in Connecticut in the 18th-century

- Timeline of Hartford, Connecticut

Notes

- "Connecticut State Name Origin". Statesymbolsusa.org. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

- https://www.iaismuseum.org/research-and-collections/research-faq/

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 21, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Steven T. Katz, "The Pequot War Reconsidered." New England Quarterly (1991) 64#2 pp: 206-224. in JSTOR

- Charles M. Andrews, The Colonial Period of American History: The Settlements II (1936) pp 144-94

- Edward Channing, History of the United States (1905) 1:408-11

- Isabel M. Calder, The New Haven Colony (1934) ch 1-3

- Andrews, The Colonial Period of American History: The Settlements II (1936) pp 187-94

- Fiske, John (1889). Beginnings of New England, or the Puritan Theocracy in its Relation to Civil and Religious Liberty. Cambridge: Houghton Mifflin Company, the Riverside Press. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-1410205490.

- Andrews, The Colonial Period of American History: The Settlements II (1936) pp 100-43

- Warren, Connecticut Unscathed : Victory in the Great Narragansett War, 1675 - 1676.

- Harold E. Selesky, War and Society in Colonial Connecticut (1990)

- Joseph A. Conforti (2003). Imagining New England: Explorations of Regional Identity from the Pilgrims to the Mid-Twentieth Century: Explorations of Regional Identity from the Pilgrims to the Mid-twentieth Century. U of North Carolina Press. p. 111.

- Richard L. Bushman (1970). From Puritan to Yankee: Character and the Social Order in Connecticut, 1690-1765. Harvard University Press.

- Wesley W. Horton (2012). The Connecticut State Constitution. Oxford University Press. p. 10.

- Williston Walker, The Creeds and Platforms of Congregationalism (1960)

- Bushman (1970). From Puritan to Yankee: Character and the Social Order in Connecticut, 1690-1765. p. 151.

- Patricia U. Bonomi (1986). Under the Cope of Heaven: Religion, Society, and Politics in Colonial America. Oxford University Press. pp. 162–68.

- Selesky, War and Society in Colonial Connecticut (1990) pp 58-66

- "America's Founding Documents | National Archives" (PDF). Archives.gov. October 12, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "Military Science | Academics | WPI". Wpi.edu. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- Poirier, David A., "Camp Reading: Logistics of a Revolutionary War Winter Encampment," Archived October 20, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Northeast Historical Archaeology Volume 5 Issue 1, 1976. Retrieved April 27, 2014

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved May 17, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Key to the Northern Country: The Hudson River Valley in the American Revolution. Books.google.com. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- Richard J. Purcell, Connecticut in Transition: 1775–1818 1963. p. 190.

- Noble E. Cunningham, Jr. The Jeffersonian Republicans in Power: Party Operations 1801–1809 (1963) p 129

- Glenn S. Gordinier, The Rockets' Red Glare: The War of 1812 and Connecticut (2012)

- Stephanie Reitz (November 23, 2009). "Group tries to preserve 2 historic Conn. homes". Associate Press. Boston Globe. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- Wormley, G. Smith. "The Journal of Negro History", "Prudence Crandall", Vol. 8, No. 1, Jan. 1923.

- STATE OF CONNECTICUT, Sites º Seals º Symbols Archived December 10, 2010, at the Wayback Machine; Connecticut State Register & Manual; retrieved on May 31, 2013

- Van Dusen, Connecticut pp 224-38

- Matthew Warshauer, Connecticut in the American Civil War: Slavery, Sacrifice, and Survival (Wesleyan University Press, 2011)

- William Augustus Croffut; John Moses Morris (1869). The Military and Civil History of Connecticut During the War of 1861-65: Comprising a Detailed Account of the Various Regiments and Batteries, Through March, Encampment, Bivouac, and Battle; Also Instances of Distinguished Personal Gallantry, and Biographical Sketches of Many Heroic Soldiers: Together with a Record of the Patriotic Action of Citizens at Home, and of the Liberal Support Furnished by the State in Its Executive and Legislative Departments. Ledyard Bill – via Internet Archive.

- Joanna D. Cowden, "The Politics of Dissent: Civil War Democrats in Connecticut," New England Quarterly (1983) 56#4 pp. 538-554 DOI: 10.2307/365104 in JSTOR

- Jarlath Robert Lane, A Political History of Connecticut During the Civil War (1941)

- Van Dusen, Connecticut pp 324-25

- Edward Chase Kirkland, Men, Cities and Transportation, A Study of New England History 1820-1900 (1948), vol 2 pp 72-110, 288-306

- Vincent P. Carosso (1987). The Morgans: Private International Bankers, 1854-1913. Harvard UP. pp. 607–10.

- John L. Weller, The New Haven Railroad: its rise and fall (1969)

- Peter Temin, ed., Engines of Enterprise: An Economic History of New England (2000) p 185

- Albert E. Van Dusen, Connecticut (1961) p 261

- Van Dusen, Connecticut (1961) pp 262-63

- Duane Lockard, New England State Politics (1959) p 245

- Van Dusen, Connecticut (1961) p 266-68

- William J. Breen, "Mobilization and Cooperative Federalism: The Connecticut State Council of Defense, 1917‐1919." Historian (1979) 42#1 pp 58-84

- Thomas Banit, "A City Goes to War: A Case Study of Bridgeport, Connecticut, 1914-1917," New England Journal of History (1989) 46#1 pp 29-53

- Ralph D. Arcafri and Hudson Birden, "The 1918 Influenza Epidemic in Connecticut," Connecticut History (1997) 38#1 pp 28-43.

- Eleanor Charles (April 7, 1996). "In the Region/Connecticut;15 Synagogues Gain National Landmark Status". New York Times.

Jews who may desire to unite and form religious societies shall have the same rights, powers and privileges which are given to Christians of every denomination.

- David Bosso, "The Evolution of Loyalty: The Americanization of Italians in Waterbury, Connecticut from the Turn of the Century to the Fall of Mussolini," Connecticut History (2008) 47#1 pp 69-95.

- Christopher M. Sterba, "'More than Ever, We Feel Proud to Be Italians': World War I and the New Haven Colonia, 1917-1918," Journal of American Ethnic History (2001): 70-106 in JSTOR.

- Christopher M. Sterba, Good Americans: Italian and Jewish Immigrants During the First World War (2003) pp 132, 141, 144, 146, 152, 204-5

- Michael T. Urbanski, "Money, War, and Recruiting an Army: The Activities of Connecticut Polonia During World War I," Connecticut History (2007) 46#1 pp 45-69.

- Stephen M. DiGiovanni, The Catholic Church in Fairfield County: 1666–1961, (1987, William Mulvey Inc., New Canaan), Chapter II: The New Catholic Immigrants, 1880–1930; subchapter: "The True American: White, Protestant, Non-Alcoholic," pp. 81–82; DiGiovanni, in turn, cites (Footnote 209, page 258) Jackson, Kenneth T., The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915–1930 (New York, 1981), p. 239

- David A. Chalmers, Hooded Americanism, The History of the Ku Klux Klan (1981), p. 268

- "The Great New England Hurricane of 1938", National Weather Service. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ""Remembering the Great Hurricane of '38,"". The New York Times. September 21, 2003. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- Peck, Merton J. & Scherer, Frederic M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis (1962) Harvard Business School p.111

- Neal R. Peirce, The New England States: People, Politics, and Power in the Six New England States (1976) 221-27

- Neal R. Peirce, The New England States: People, Politics, and Power in the Six New England States (1976) p 226

- Joseph I. Lieberman, The Power Broker: A Biography of John M. Bailey, Modern Political Boss (1966).

- Michael Barone, et al. The Almanac of American Politics: 1976 (1975), pp 140-41

- Joseph I. Lieberman, The Legacy: Connecticut Politics, 1930-1980 (1981).

- Jon E. Purmont. Ella Grasso: Connecticut's Pioneering Governor (2012)

- "Grasso Closes the State" by proclamation". Connecticut State Library. Archived from the original on February 6, 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- Neal R. Peirce and Jerry Hagstrom, The Book of America: Inside the Fifty States Today (1983) p 182

- Associated Press, "Indian casinos struggle to get out from under debt," January 21, 2012 online

- Associated Press listing as it appeared in The Advocate of Stamford, September 12, 2006, page A4

- Von Zielbauer, Paul (March 20, 2003). "Bridgeport Mayor Convicted On 16 Charges of Corruption". The New York Times.

- Von Zielbauer, Paul (March 22, 2003). "Ex-Mayor in Sex Trial Opens Door to Bribery Questions". The New York Times.

- "Connecticut Archives". Aarp.org. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- Archived October 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Death Penalty: House Votes To Repeal Death Penalty". Courant.com. April 12, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "Connecticut Death Penalty Faces Second Vote In General Assembly « CBS New York". Newyork.cbslocal.com. April 11, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "Hurricane Irene one year later: Storm cost $15.8 in damage from Florida to New York to the Caribbean", New York Daily News, August 27, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- "Report on Transmission Facility Outages During the Northeast Snowstorm of October 29–30, 2011" (PDF). Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and North American Electric Reliability Corporation. May 12, 2012. pp. 8–16. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- "Hurricane Sandy Fast Facts". CNN.com. November 2, 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- "Conn. Gov.: State's Damage From Superstorm Sandy $360M and Climbing," Insurance Journal, November 16, 2012. Retrieved May 17, 2014

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Further reading

Surveys

- Andersen, Ruth O. M. From Yankee to American: Connecticut, 1865-1914 (Series in Connecticut history) (1975) 96pp

- Andrews, Charles M. The Colonial Period of American History: The Settlements, volume 2 (1936) pp 67–194, by leading scholar

- Atwater, Edward Elias (1881). History of the Colony of New Haven to Its Absorption Into Connecticut. author. to 1664

- Burpee, Charles W. The story of Connecticut (4 vol 1939); detailed narrative in vol 1-2

- Clark, George Larkin. A History of Connecticut: Its People and Institutions (1914) 608 pp; based on solid scholarship online

- Federal Writers' Project. Connecticut: A Guide to its Roads, Lore, and People (1940) famous WPA guide to history and to all the towns online

- Fraser, Bruce. Land of Steady Habits: A Brief History of Connecticut (1988), 80 pp, from state historical society

- Hollister, Gideon Hiram (1855). The History of Connecticut: From the First Settlement of the Colony to the Adoption of the Present Constitution. Durrie and Peck., vol. 1 to 1740s

- Janick, Herbert F. A diverse people: Connecticut, 1914 to the present (Series in Connecticut history) (1975) 124pp

- Jones, Mary Jeanne Anderson. Congregational Commonwealth: Connecticut, 1636-1662 1968

- Morse, Jarvis. Under the Constitution of 1818: The First Decade (1939) online 24pp

- Peirce, Neal R. The New England States: People, Politics, and Power in the Six New England States (1976) pp 182–231; updated in Neal R. Peirce and Jerry Hagstrom, The Book of America: Inside the Fifty States Today (1983) pp 153–75

- Peters, Samuel. General History of Connecticut (1989)

- Purcell, Richard J. Connecticut in Transition: 1775–1818 (1963); standard scholarly history online

- Roth, David M. and Freeman Meyer. From Revolution to Constitution: Connecticut, 1763-1818 (Series in Connecticut history) (1975) 111pp

- Sanford, Elias Benjamin (1887). A history of Connecticut. S.S. Scranton.; very old textbook; strongest on military history, and schools

- Taylor, Robert Joseph. Colonial Connecticut: A History (1979); standard scholarly history

- Trumbull, Benjamin (1818). Complete History of Connecticut, Civil and Ecclesiastical. very old history; to 1764

- Trecker, Janice Law. Preachers, rebels, and traders: Connecticut, 1818-1865 (Series in Connecticut history) (1975) 95pp

- Van Dusen, Albert E. Connecticut A Fully Illustrated History of the State from the Seventeenth Century to the Present (1961) 470pp the standard survey to 1960, by a leading scholar

- Van Dusen, Albert E. Puritans against the wilderness: Connecticut history to 1763 (Series in Connecticut history) 150pp (1975)

- Warshauer, Matthew. Connecticut in the American Civil War: Slavery, Sacrifice, and Survival (Wesleyan University Press, 2011) 309 pages;

- Zeichner, Oscar. Connecticut's Years of Controversy, 1750-1776 (1949)

Specialized studies

- Buell, Richard, Jr. Dear Liberty: Connecticut's Mobilization for the Revolutionary War (1980), major scholarly study

- Bushman, Richard L. (1970). From Puritan to Yankee: Character and the Social Order in Connecticut, 1690-1765. Harvard University Press.

- Collier, Christopher. Roger Sherman's Connecticut: Yankee Politics and the American Revolution (1971)

- Daniels, Bruce C. "Economic Development in Colonial and Revolutionary Connecticut: An Overview," William and Mary Quarterly (1980) 37#3 pp. 429–450 in JSTOR

- Daniels, Bruce Colin. The Connecticut town: Growth and development, 1635-1790 (Wesleyan University Press, 1979)

- Daniels, Bruce C. "Democracy and Oligarchy in Connecticut Towns-General Assembly Officeholding, 1701-1790" Social Science Quarterly (1975) 56#3 pp: 460–475.

- Fennelly, Catherine. Connecticut women in the Revolutionary era (Connecticut bicentennial series) (1975) 60pp

- Grant, Charles S. Democracy in the Connecticut Frontier Town of Kent (1970)

- Hooker, Roland Mather. The Colonial Trade of Connecticut (1936) online; 44pp

- Lambert, Edward Rodolphus (1838). History of the Colony of New Haven: Before and After the Union with Connecticut. Containing a Particular Description of the Towns which Composed that Government, Viz., New Haven, Milford, Guilford, Branford, Stamford, & Southold, L. I., with a Notice of the Towns which Have Been Set Off from "the Original Six.". Hitchcock & Stafford.

- Jeffries, John W. Testing the Roosevelt Coalition: Connecticut Society and Politics in the Era of World War II (1979), voters & politics

- Lockard, Duane. New England State Politics (1959) pp 228–304; covers 1932-1958

- Main, Jackson Turner. Connecticut Society in the Era of the American Revolution (pamphlet in the Connecticut bicentennial series) (1977)

- Morse, Jarvis M. The Rise of Liberalism in Connecticut, 1828–1850 (1933) online

- Pierson, George Wilson. History of Yale College (2 vol 1952) scholarly history to 1937

- Selesky Harold E. War and Society in Colonial Connecticut (1990) 278 pp.

- Steiner, Bernard C. History of Slavery in Connecticut (1893)

- Taylor, John M. The Witchcraft Delusion in Colonial Connecticut, 1647-1697 (1969) online

- Trumbull, James Hammond (1886). The memorial history of Hartford County, Connecticut, 1633-1884. E. L. Osgood., vol. 1 is online; 700pp; comprehensive coverage; vol 2 not online is biographies of civil leaders in 1880s

- Warren, Jason W. Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in the Great Narragansett War, 1675–1676 (U of Oklahoma Press, 2014). xiv, 249 pp.

- Williams, Stanley Thomas. The Literature of Connecticut (1936), short pamphlet online

Regional studies with coverage of Connecticut

- Adams, James Truslow. The Founding of New England (1921); Revolutionary New England, 1691–1776 (1923) online; New England in the Republic, 1776–1850 (1926) online

- Andrews, Charles M. The Fathers of New England: A Chronicle of the Puritan Commonwealths (1919) online

- Axtell, James, ed. The American People in Colonial New England (1973)

- Black, John D. The rural economy of New England: a regional study (1950) online

- Brewer, Daniel Chauncey. Conquest of New England by the Immigrant (1926)

- Conforti, Joseph A. Imagining New England: Explorations of Regional Identity from the Pilgrims to the Mid-Twentieth Century (2001)

- Cumbler, John T. Reasonable Use: The People, the Environment, and the State, New England, 1790-1930 (2001) online

- Hall, Donald, ed. Encyclopedia of New England (2005)

- Karlsen, Carol F. The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England (1998)

- Kirkland, Edward Chase. Men, Cities and Transportation, A Study of New England History 1820-1900 (2 vol. 1948)

- McSeveney, Samuel T. Politics of Depression: Political Behavior in the Northeast, 1893-1896 (1972) voting behavior in Connecticut, New York and New Jersey

- Palfrey, John Gorham. History of New England (5 vol 1859–90) online

- Weeden, William Babcock (1890). Economic and social history of New England, 1620-1789. Houghton, Mifflin. vol 1 online

- Zimmerman, Joseph F. New England Town Meeting: Democracy in Action (1999)

Historiography

- Daniels, Bruce C. "Antiquarians and Professionals: The Historians of Colonial Connecticut," .Connecticut History (1982), 23#1, pp 81-97.

- Meyer, Freeman W. "The Evolution of the Interpretation of Economic Life in Colonial Connecticut," Connecticut History (1985) 26#1 pp 33-43.

Primary sources

- Dwight, Timothy. Travels Through New England and New York (circa 1800) 4 vol. (1969) Online at: vol 1; vol 2; vol 3; vol 4

- McPhetres, S. A. A political manual for the campaign of 1868, for use in the New England states, containing the population and latest election returns of every town (1868)

External links

- Connecticut Historical Society

- ConnecticutHistory.org

- Changing Connecticut, 1634 – 1980 - Yale-New Haven Teachers Institute