Liberty Tree

The Liberty Tree (1646–1775) was a famous elm tree that stood in Boston near Boston Common, in the years before the American Revolution. In 1765, colonists in Boston staged the first act of defiance against the British government at the tree. The tree became a rallying point for the growing resistance to the rule of Britain over the American colonies, and the ground surrounding it became known as Liberty Hall. The Liberty Tree was felled by Loyalist Nathaniel Coffin Jr. in August 1775.[1]

History

Stamp Act protests

In 1765 the British government imposed a Stamp Act on the American colonies. It required all legal documents, permits, commercial contracts, newspapers, pamphlets, and playing cards in the American colonies to carry a tax stamp. Colonists were outraged. In Boston, a group of local businessmen calling themselves the Loyal Nine began meeting in secret to plan a series of protests against the Stamp Act.[2]

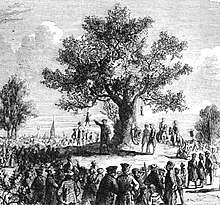

On August 14, 1765, a crowd gathered in Boston under a large elm tree at the corner of Essex Street and Orange Street (the latter of which was renamed Washington Street) to protest the hated Stamp Act. Hanging from the tree was a straw-stuffed effigy labeled "A. O." for Andrew Oliver, the colonist chosen by King George III to impose the Stamp Act. Beside it hung a British cavalry jackboot, its sole painted green. This second effigy represented the two British ministers who were considered responsible for the Stamp Act: the Earl of Bute (the boot being a pun on "Bute") and Lord George Grenville (the green being a pun on "Grenville").[3] Peering up from inside the boot was a small devil figure, holding a copy of the Stamp Act and bearing a sign that read, "What Greater Joy did ever New England see / Than a Stampman hanging on a Tree!"[4] This was the first public show of defiance against the Crown and spawned the resistance that led to the American Revolutionary War 10 years later.

The tree became a central gathering place for protesters, and the ground surrounding it became popularly known as Liberty Hall.[5] A liberty pole was installed nearby with a flag that could be raised above the tree to summon the townspeople to a meeting. Ebenezer Mackintosh, a shoemaker who handled much of the hands-on work of hanging effigies and leading angry mobs, became known as "Captain General of the Liberty Tree."[3] Paul Revere included the Liberty Tree in an engraving, "A View of the Year 1765."[4]

When the Stamp Act was repealed in 1766, townspeople gathered at the Liberty Tree to celebrate. They decorated the tree with flags and streamers, and when evening fell, hung dozens of lanterns from its branches.[4] A copper sign was fastened to the trunk which read, "This tree was planted in the year 1646, and pruned by order of the Sons of Liberty, Feb. 14th, 1766."[5] Soon colonists in other towns, from Newport, Rhode Island to Charleston, South Carolina, began naming their own liberty trees, and the Tree of Liberty became a familiar symbol of the American Revolution.[3]

Other protests

%2C_The_Bostonians_Paying_the_Excise-man%2C_or_Tarring_and_Feathering_(1774)_-_02.jpg)

The Loyal Nine eventually became part of a larger group, the Sons of Liberty.[2] They continued to use the Liberty Tree as a gathering place for protests, leading loyalist Peter Oliver to write bitterly in 1781,

This Tree stood in the Town, & was consecrated for an Idol for the Mob to Worship; it was properly the Tree ordeal, where those, whom the Rioters pitched upon as State delinquents, were carried to for Trial, or brought to as the Test of political Orthodoxy.[6]

During the Liberty Riot of 1768, to protest the seizure of John Hancock's ship by the Royal Navy, townspeople dragged a customs commissioner's boat out of the harbor all the way to the Liberty Tree, where it was condemned at a mock trial and burned on Boston Common. Two years later, a funeral procession for the victims of the Boston Massacre passed by the tree.[4] It was also the site of protests against the Tea Act. In 1774, a customs official and staunch loyalist named John Malcolm was stripped to the waist, tarred and feathered, and forced to announce his resignation under the tree.[7] The following year, Thomas Paine published an ode to the Liberty Tree in the Pennsylvania Gazette.[4]

In the years leading up to the war, the British made the Liberty Tree an object of ridicule. British soldiers tarred and feathered a man named Thomas Ditson, and forced him to march in front of the tree.[8] During the Siege of Boston, a party of British soldiers and Loyalists led by Job Williams cut the tree down, knowing what it represented to the patriots, and used it for firewood.[5] Later, in the Raid on Charlottetown (1775), American privateers sought revenge against the man who cut the tree down, Loyalist Nathaniel Coffin Jr.

Following the British evacuation in 1776, patriots returning to Boston erected a liberty pole at the site. For many years the tree stump was used as a reference point by local citizens, similar to the Boston Stone.[7] During an 1825 tour of Boston, the Marquis de Lafayette declared, "The world should never forget the spot where once stood Liberty Tree, so famous in your annals."[4]

Memorials

At the 1964 New York World's Fair a sculpture of the tree designed by Albert Surman was a featured exhibit in the New England Pavilion. When the Liberty Tree Mall was opened in 1972, the sculpture was installed at center court.

In October 1966, the Boston Herald began running stories pointing out that the only commemoration of the Liberty Tree site was a grimy plaque, installed in the 1850s,[4] on a building at 630 Washington Street three stories above what is now the intersection of Essex and Washington Streets, a block east of the Boston Common. Reporter Ronald Kessler found that the plaque was covered with bird droppings and obscured by a Kemp's hamburger sign. Local guidebooks did not mention it.[9]

To call attention to how obscure the site had become, Kessler interviewed waitresses at the Essex Delicatessen below the plaque on Washington Street. None knew what the Liberty Tree was. "The Liberty Tree? That's a roast beef sandwich with a slice of Bermuda onion, Russian dressing, and a side of potato salad," said one waitress who had worked beneath the plaque for 20 years.[9]

Kessler persuaded then Massachusetts Governor John A. Volpe to visit the site. A photo of Volpe examining the plaque from a fire engine ladder appeared on page one of the 6 October 1966 edition of the Boston Herald.[10] According to Kessler, Volpe promised to preserve the site in the form of a park with monuments, and "Edward J. Logue, the administrator of the Boston Redevelopment Authority, said the park would be a 'handsome, open space' with grass, benches, plaques explaining the history of the tree, and 'the largest elm tree that can be transported and is resistant to Dutch elm disease.' ... That promise was never fulfilled." Kessler explored the subject further and presented the entire history of the Liberty Tree in "America Must Remember Boston's Liberty Tree".[11]

In 1974, funding was approved for a small park at Washington and Essex, which at that time was part of an area known as the Combat Zone.[12] Plans to plant trees there had to be scrapped because there were too many underground utilities.[13] The Boston Redevelopment Authority ultimately placed a small bronze plaque in the sidewalk across the street from the bas relief plaque. The plaque bears the inscription "SONS OF LIBERTY, 1766; INDEPENDENCE of their COUNTRY, 1776."[11]

In December 2018, the city finally opened a suitable plaza commemorating the Liberty Tree. Called Liberty Tree Plaza, it is at 2 Boylston Street across the street from the original bas relief with tables and chairs, landscaping, lighting, an elm tree to commemorate the original tree that British soldiers cut down in 1775 before the outbreak of the American Revolution, and a stone monument inscribed with the history of the Liberty Tree. The Liberty Tree "became a rallying point for colonists protesting the British-imposed Stamp Act in 1765 and became an important symbol of their cause," the inscription says. "These 'Sons of Liberty' began the struggle that led to the Revolutionary War and American independence." [14]

Boston's Old State House museum houses a remnant of the flag that flew above the Liberty Tree, and one of the original lanterns that were hung from the tree during the Stamp Act repeal celebration in 1766.[4]

Other trees

Many other towns designated their own Liberty Trees. Most have been lost over time, although Randolph, New Jersey claims a white oak Liberty Tree dating to 1720.[15] A 400-year-old tulip poplar stood on the grounds of St. John's College in Annapolis, Maryland until 1999, when it was felled after Hurricane Floyd caused irreparable damage to it.[16] The Liberty Tree in Acton, Massachusetts, was an elm tree that lasted until about 1925. In 1915, knowing that the Liberty Tree was getting older, Acton students planted the Peace Tree, a maple that still stands today.[17]

The Arbres de la liberté ("Liberty Trees"), inspired by the American example, were a symbol of the French Revolution, the first being planted in 1790 by a pastor of a Vienne village, inspired by the Liberty Tree of Boston. The last surviving liberty elm in France from c.1790 still stands in the parish of La Madeleine at Faycelles, in the Département de Lot.[18] Liberty trees were also planted on the Place Royale in Brussels on July 9, 1794, after the occupation of the Austrian Netherlands by French revolutionary forces,[19] and on Dam Square in Amsterdam on January 19, 1795, in celebration of the alliance between the French Republic and the Batavian Republic.[20]

Tipu Sultan gave his support to French soldiers at Srirangapatna in setting Jacobin club in 1797. Tipu himself called Citizen Tipu and he planted the Tree of Liberty at srirangapatana.

In 1798, with the establishing of the short-lived Roman Republic, such a tree was also planted in Rome's Piazza delle Scole, to mark the legal abolition of the Roman Ghetto (which was, however, re-instated with the resumption of Papal rule). The last surviving liberty elm in Italy, planted in 1799 to celebrate the new Parthenopean Republic, stood until recently in Montepaone, Calabria. The tree was badly damaged in a storm in 2008 and has been replaced by a clone.[21]

As students at the Tübinger Stift, the German philosopher Georg Hegel and his friend Friedrich Schelling planted a liberty tree on the outskirts of Tübingen, Germany.[22]

Besides actual trees, the term "Tree of Liberty" is associated with a quotation from a 1787 letter written by Thomas Jefferson to William Stephens Smith: "The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants."[23]

See also

- "Liberty Tree", a poem by Thomas Paine (Wikisource)

- Pine Tree Flag, sometimes called the Liberty Tree Flag

- Liberty Generation

- Sir Francis Bernard, 1st Baronet

- Liberty Tree Foundation for the Democratic Revolution

References

- The Loyalists of Massachusetts And the Other Side of the American Revolution By James Henry Stark

- "The Loyal Nine of Boston: The Predecessors of the Sons of Liberty". Boston Tea Party Ships & Museum.

- Young, Alfred F. (2012). "Ebenezer Mackintosh: Boston's Captain General of the Liberty Tree". Revolutionary Founders: Rebels, Radicals, and Reformers in the Making of the Nation. Knopf Doubleday. pp. 15–34. ISBN 9780307455994.

- Trickey, Erick (19 May 2016). "The Story Behind a Forgotten Symbol of the American Revolution: The Liberty Tree". Smithsonian Magazine.

- Drake, Samuel Adams (1873). "Liberty Tree and the Neighborhood". Old Landmarks and Historic Personages of Boston. Profusely Illustrated. J. R. Osgood. pp. 396–415.

- Oliver, Peter (1967) [1781]. Peter Oliver's Origin & Progress of the American Rebellion: A Tory View. Stanford University Press. p. 54. ISBN 9780804706018.

- Young, Alfred F. (2001). The Shoemaker and the Tea Party: Memory and the American Revolution. Beacon Press. pp. 49, 118. ISBN 9780807071427.

- "Deposition of Thomas Ditson". American Archives, Northern Illinois University.

- Boston Herald, October 2, 1966, Section One.

- Boston Herald, October 6, 1966, p. 1.

- Kessler, Ronald (3 October 2011). "America Must Remember Boston's Liberty Tree". Newsmax. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- Yudis, Anthony (21 April 1974). "Lots and Blocks/Something new for the Combat Zone—Liberty Tree Park". The Boston Globe.

- Jones, Arthur (6 June 1974). "Downtown Boston planting runs into $1 million problem". The Boston Globe.

- "Revolutionary War Heroes Remembered at Reopening of Liberty Plaza in Chinatown". Boston Globe. 4 December 2018. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- "Randolph's Liberty Tree to Live On". Township of Randolph. 13 March 2014. Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Morley, Jefferson (25 October 1999). "Liberty Tree Is Felled". The Washington Post.

- "Liberty Tree Site and Simon Hunt Farm". Acton Historical Society.

- "'L'olmo, l'albero della libertà". GiuseppeMusolino.it (in Italian).

- Alain de Gueldre et al., Kroniek van België (Antwerp and Zaventem, 1987), p. 515.

- "1795-1806 Liberty Tree". Rijksmuseum.nl.

- "L'Olmo Storico di Montepaone, Ultimo Albero della Libertà". Calabria Online (in Italian).

- Plant, Raymond (2013). Hegel. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 9781136526329.

- "To William S. Smith Paris, Nov. 13, 1787". American History from Revolution to Reconstruction and Beyond.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Liberty Tree. |

- "A View of the Year 1765" by Paul Revere (engraving)

- "America Must Remember Boston's Liberty Tree" by Ronald Kessler

- "Liberty Tree" by Thomas Paine (poem)

- Otis, James (1896). Under the Liberty Tree: A Story of The 'Boston Massacre'. Boston: Estes & Lauriat.

- Young, Alfred F. (2006). Liberty Tree: Ordinary People and the American Revolution. NYU Press.