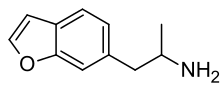

6-APB

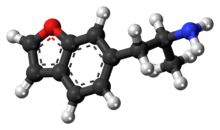

6-APB (6-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran) is an empathogenic psychoactive compound of the substituted benzofuran and substituted phenethylamine classes. 6-APB and other compounds are sometimes informally called "Benzofury" in newspaper reports. It is similar in structure to MDA, but differs in that the 3,4-methylenedioxyphenyl ring system has been replaced with a benzofuran ring. 6-APB is also the unsaturated benzofuran derivative of 6-APDB. It may appear as a tan grainy powder. While the drug never became particularly popular, it briefly entered the rave and underground clubbing scene in the UK before its sale and import were banned. It falls under the category of research chemicals, sometimes called "legal highs." Because 6-APB and other substituted benzofurans have not been explicitly outlawed in some countries, they are often technically legal, contributing to their popularity.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

|

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C11H13NO |

| Molar mass | 175.231 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

6-APB is a serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI) with Ki values of 117, 150, and 2698 nM for the norepinephrine transporter (NET), dopamine transporter (DAT), and serotonin transporter (SERT), respectively.[1] In addition, 6-APB not only blocks the reuptake of these monoamine neurotransmitters but is also a releasing agent of them; that is, it is a serotonin-norepinephrine-dopamine releasing agent (SNDRA).[2] In addition to actions at the monoamine transporters, 6-APB is a potent full agonist of the serotonin 5-HT2B receptor (Ki = 3.7 nM),[1][1] with higher affinity for this target than any other site.[3] Moreover, unlike MDMA, 6-APB shows 100-fold selectivity for the 5-HT2B receptor over the 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C receptors.[3][4] It is notably both more potent and more selective as an agonist of the 5-HT2B receptor than the reference 5-HT2B receptor agonist, BW-723C86, which is commonly used for research into the 5-HT2B receptor. Aside from the 5-HT2B receptor, 6-APB has also been found to bind with high affinity to the α2C-adrenergic receptor subtype (Ki = 45 nM), although the clinical significance of this action is unknown.[1] 6-APB showed little other affinity at a wide selection of other sites.[1]

The potent agonism of the 5-HT2B receptor makes it likely that 6-APB would be cardiotoxic with chronic or long-term use, as seen with other 5-HT2B receptor agonists such as the withdrawn serotonergic anorectic fenfluramine.[1][5]

Pharmacokinetics

The pharmacokinetics of 6-APB have not been studied, however, some information can be extracted from user reports. These suggest a slow onset of 40–120 minutes. The drugs peak effects last 7 hours, followed by a comedown phase of approximately 2 hours, and after effects for up to 24 hours.[6]

Metabolism

Although limited literature is available, there is some data on metabolism of 6-APB in rats. Its Phase I metabolism involves hydroxylation of the furan ring, then cleavage of the ring, followed by a reduction of the unsaturated aldehyde from the previous step. The resulting aldehyde may then take two paths. It is either oxidized to a carboxylic acid or reduced to an alcohol, and then hydroxylated. Phase II metabolism consists of glucuronidation. The most prevalent metabolites in rats were 3-carboxymethyl-4-hydroxyamphetamine and 4-carboxymethyl-3-hydroxyamphetamine.[7]

Chemistry

6-APB and its structural isomer 5-APB have been tested with a series of agents including: Marquis, Liebermann, Mecke, and Froehde reagents. Exposing compounds to the reagents gives a colour change which is indicative of the compound under test.

| Compound | Marquis | Liebermann | Mecke | Froehde |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-APB | Black | Black | Black | Dark Purple |

| 6-APB | Purple | Dark Purple | Purple | Purple |

6-APB succinate is reported to be practically insoluble in CHCl3 as well as very minimally soluble in cold water. A batch seized by the DEA contained a 2:1 ratio of succinate to 6-APB.[9]

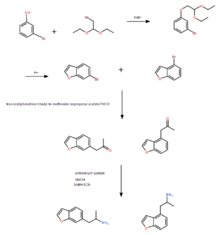

Synthesis

The synthesis by Briner et al.[4] entailed refluxing 3-bromophenol with bromoacetaldehyde and sodium hydride to give the diethyl acetal, which then was heated with polyphosphoric acid to give a mixture of bromobenzofuran structural isomers: 4-bromo-1-benzofuran and 6-bromo-1-benzofuran. The isomers were separated by silica gel column chromatography, then converted to their respective propanone derivatives, and then reductively aminated to give 6-APB and 4-APB, both of which were converted to their HCl ion pairs for further examination.

Law

Canada

In 1999, amphetamines were changed from Schedule III to Schedule I as a result of the Safe Streets Act. Some have speculated that 6-APB's structure qualifies it as a Schedule I drug as an analog of MDA.[11]

In 2014, a study funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research noted that 6-APB "may or may not be legal in Canada depending on how one interprets the current Act"[12] and that it could be purchased for academic purposes without an exemption from Health Canada. The study also noted how, unlike the MDMA it often serves as a replacement for in countries like the US, 6-APB's benzofuran structure does not make it a direct analogue of amphetamine despite similarities in effects.

France

6-APB is unscheduled in France.

Italy

6-APB is illegal in Italy.[13]

Germany

6-APB is illegal in Germany since the 17th of July, 2013, when it was added to Anlage II of the Betäubungsmittelgesetz.

Netherlands

6-APB is not listed under the Opium Law or the Medicine Act in the Netherlands, and thus currently legal.

New Zealand and Australia

Certain countries contain a "substantially similar" catch-all clause in their drug law, such as New Zealand and Australia. This includes 6-APB as it is similar in chemical structure to the class A drug MDA, meaning 6-APB may be viewed as a controlled substance analogue in these jurisdictions.[14]

Sweden

In Sweden, as of 27 December 2009 6-APB is classified as "health hazard" under the act Lagen om förbud mot vissa hälsofarliga varor (translated Act on the Prohibition of Certain Goods Dangerous to Health).[15]

UK

On June 10, 2013 6-APB and a number of analogues were classified as Temporary Class Drugs in the UK following an ACMD recommendation.[5] This means that sale and import of the named substances are criminal offences and are treated as for class B drugs.[16] On November 28, 2013 the ACMD recommended that 6-APB and related benzofurans should become Class B, Schedule 1 substances.[5] On March 5, 2014 the UK Home Office announced that 6-APB would be made a class B drug on 10 June 2014 alongside every other benzofuran entactogen and many structurally related drugs.[17]

United States

6-APB is not scheduled at the federal level in the United States,[18] but it may be considered an analog of amphetamine, in which case purchase, sale, or possession could be prosecuted under the Federal Analog Act.[19]

References

- Iversen L, Gibbons S, Treble R, Setola V, Huang XP, Roth BL (January 2013). "Neurochemical profiles of some novel psychoactive substances". European Journal of Pharmacology. 700 (1–3): 147–51. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.12.006. PMC 3582025. PMID 23261499.

- Rickli A, Kopf S, Hoener MC, Liechti ME (July 2015). "Pharmacological profile of novel psychoactive benzofurans". British Journal of Pharmacology. 172 (13): 3412–25. doi:10.1111/bph.13128. PMC 4500375. PMID 25765500.

- Canal CE, Murnane KS (January 2017). "2C receptor and the non-addictive nature of classic hallucinogens". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 31 (1): 127–143. doi:10.1177/0269881116677104. PMC 5445387. PMID 27903793.

- US patent 7045545, Karin Briner, Joseph Paul Burkhart, Timothy Paul Burkholder, Matthew Joseph Fisher, William Harlan Gritton, Daniel Timothy Kohlman, Sidney Xi Liang, Shawn Christopher Miller, Jeffrey Thomas Mullaney, Yao-Chang Xu, Yanping Xu, "Aminoalkylbenzofurans as serotonin (5-HT(2c)) agonists", published 19 January 2000, issued 16 May 2006

- Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, Jeremy Browne (4 June 2013). "Temporary class drug order on benzofury and NBOMe compounds - letter from ACMD". GOV.UK.

- Shaun L. Greene (2013). Novel Psychoactive Substances: Classification, Pharmacology and Toxicology Chapter 16 – Benzofurans and Benzodifurans. Boston: Academic Press. pp. 383–392. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-415816-0.00016-X. ISBN 9780124158160.

- Nugteren-van Lonkhuyzen JJ, van Riel AJ, Brunt TM, Hondebrink L (December 2015). "Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and toxicology of new psychoactive substances (NPS): 2C-B, 4-fluoroamphetamine and benzofurans". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 157: 18–27. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.011. PMID 26530501.

- Chan WL, Wood DM, Hudson S, Dargan PI (September 2013). "Acute psychosis associated with recreational use of benzofuran 6-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran (6-APB) and cannabis". Journal of Medical Toxicology. 9 (3): 278–81. doi:10.1007/s13181-013-0306-y. PMC 3770991. PMID 23733714.

- John F. Casale, Patrick A. Hays (January 2012). "The Characterization of 6-(2-Aminopropyl)benzofuran and Differentiation from its 4-, 5-, and 7-Positional Analogues" (PDF). Microgram Journal. 9 (2): 61–74.

- from:http://forendex.southernforensic.org/uploads/references/MicrogramJournal/9.2.61.74.pdf Archived 2016-03-18 at the Wayback Machine

- "Controlled Drugs and Substances Act : Definitions and Interpretations". isomerdesign.com. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- Hudson, Alan L; Lalies, Maggie D; Baker, Glen B; Wells, Kristopher; Aitchison, Katherine J (2014-04-16). "Ecstasy, legal highs and designer drug use: A Canadian perspective". Drug Science, Policy and Law. 1: 2050324513509190. doi:10.1177/2050324513509190. ISSN 2050-3245.

- "Nuove tabelle delle sostanze stupefacenti e psicotrope (DPR 309/90)" (PDF) (in Italian). Ministero della Salute.

- "Misuse of Drugs Act 1975". New Zealand Legislation. 7 November 2015.

- "Förordning (1999:58) om förbud mot vissa hälsofarliga varor" (in Swedish). Lagbevakning med Notisum och Rättsnätet. 24 November 2009.

- Home Office, Jeremy Browne (4 June 2013). "'NBOMe' and 'Benzofury' banned". GOV.UK.

- UK Home Office (28 April 2014). "The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Ketamine etc.) (Amendment) Order 2014". The National Archives.

- 21 CFR — SCHEDULES OF CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES §1308.11 Schedule I.

- Casale, John; Hays, P.A. (2011-01-01). "The Characterization of 5- and 6-(2-Aminopropyl)-2,3-dihydrobenzofuran". Microgram Journal. 8: 62–74.