Treasure

Treasure (from Latin: thesaurus from Greek language θησαυρός thēsauros, "treasure store")[2][3] is a concentration of wealth — often originating from ancient history — that is considered lost and/or forgotten until rediscovered. Some jurisdictions legally define what constitutes treasure, such as in the British Treasure Act 1996.

The phrase "blood and treasure" has been used to refer to the human and monetary costs associated with massive endeavours such as war that expend both.[4]

Searching for hidden treasure is a common theme in legend; treasure hunters do exist, and can seek lost wealth for a living.

Buried treasure

Buried treasure is an important part of the popular mythos surrounding pirates. According to popular conception, pirates often buried their stolen fortunes in remote places, intending to return for them later (often with the use of treasure maps).[5]

There are three well known stories that helped popularize the myth of buried pirate treasure:[6] "The Gold-Bug" by Edgar Allan Poe, "Wolfert Webber" by Washington Irving and Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson. They differ widely in plot and literary treatment but all are derived from the William Kidd legend.[7] Stevenson's Treasure Island was directly influenced by Irving's "Wolfert Webber", Stevenson saying in his preface "It is my debt to Washington Irving that exercises my conscience, and justly so, for I believe plagiarism was rarely carried farther.. the whole inner spirit and a good deal of the material detail of my first chapters.. were the property of Washington Irving."[7]

Although buried pirate treasure is a favorite literary theme, there are very few documented cases of pirates actually burying treasure, and no documented cases of a historical pirate treasure map.[8] One documented case of buried treasure involved Francis Drake who buried Spanish gold and silver after raiding the train at Nombre de Dios—after Drake went to find his ships, he returned six hours later and retrieved the loot and sailed for England. Drake did not create a map.[8]

The pirate most responsible for the legends of buried pirate treasure was Captain Kidd. The story was that Kidd buried treasure from the plundered ship the Quedah Merchant on Gardiners Island, near Long Island, New York, before being arrested and returned to England, where he was put through a very public trial and executed. Although much of Kidd's treasure was recovered from various people who had taken possession of it before Kidd's arrest (such as his wife and various others who were given it for safe keeping), there was so much public interest and fascination with the case at the time, speculation grew that a vast fortune remained and that Kidd had secretly buried it. Captain Kidd did bury a small cache of treasure on Gardiner's Island in a spot known as Cherry Tree Field; however, it was removed by Governor Bellomont and sent to England to be used as evidence against him.[9] Over the years many people have tried to find the supposed remnants of Kidd's treasure on Gardiner's Island and elsewhere, but none of the above has ever been found.[8]

Treasure maps

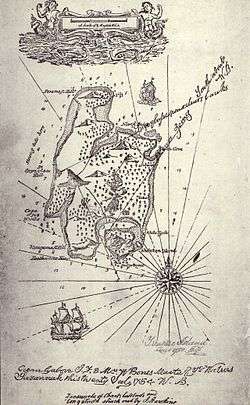

A treasure map is a variation of a map to mark the location of buried treasure, a lost mine, a valuable secret or a hidden location. One of the earliest known instances of a document listing buried treasure is the copper scroll, which was recovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls near Qumran in 1952. More common in fiction than in reality, "pirate treasure maps" are often depicted in works of fiction as hand drawn and containing arcane clues for the characters to follow.

Treasure maps have taken on numerous permutations in literature and film, such as the stereotypical tattered chart with an oversized "X" (as in "X marks the spot") to denote the treasure's location, first made popular by Robert Louis Stevenson in Treasure Island (1883) or a cryptic puzzle (in Edgar Allan Poe's "The Gold-Bug" (1843)).

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Treasures. |

See also

References

- [Spanish] Culture and Education Ministry (26 February 2003). "RESOLUCIÓN de 7 de enero de 2003, de la Dirección General de Patrimonio Artístico de la Consejería de Cultura y Educación, por la que se incoa expediente de declaración de bien de interés cultural a favor de la colección arqueológica del Tesoro de Villena" [January 7, 2003, RESOLUTION of the General Direction on Artistic Heritage of the Culture and Education Council, which opens a file on the declaration as Good of Cultural Interest (BIC) the archaeologic collection known as Treasure of Villena] (PDF). [Spanish] State Official Bulletin (BOE) (in Spanish). Madrid: Spanish Government (49): 7798–7802. Retrieved December 6, 2009.

Desde el punto de vista histórico, artístico y arqueológico, el Tesoro de Villena constituye un «unicum», un depósito no normalizado, por su peso y contenido (A. Perea). De hecho, se trata del segundo tesoro de vajilla áurea más importante de Europa, tras el de las Tumbas Reales de Micenas en Grecia (A. Mederos). (From a historic, artistic and archaeological point of view, the Treasure of Villena constitutes a "unicum", a non-normalised deposit, according to its weight and content (A. Perea). In fact, it is the second most important golden tableware finding in Europe, after that of the Royal Graves in Mycenae in Greece (A. Mederos))

- "treasure" – Online Etymology Dictionary

- θησαυρός, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus. The word has a Pre-Greek origin (R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 548).

- Lichfield, Gideon. "A history of the "blood and treasure" phrase Trump keeps using about the war in Afghanistan". Quartz. Retrieved 2020-06-20.

- Stewart, Charles (December 2003). "Dreams of Treasure". Anthropological Theory. 3 (4): 481–500. doi:10.1177/146349960334005. ISSN 1463-4996.

- Paine, pp. 27–28

- Paine, pg. 28

- Cordingly, David. (1995). Under the Black Flag: The Romance and the Reality of Life Among the Pirates. ISBN 0-679-42560-8.

- The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd, pg. 241, The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd, pg. 260