Linen

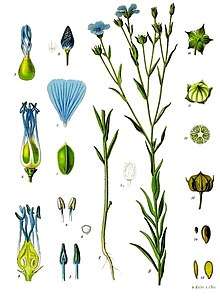

Linen (/ˈlɪnən/) is a textile made from the fibers of the flax plant.

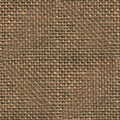

Linen is very strong and absorbent, and dries faster than cotton. Because of these characteristics, linen is comfortable to wear in hot weather and is valued for use in garments. It also has other distinctive characteristics, notably its tendency to wrinkle.[1] Many other products, including home furnishing items, are also often made from linen.

Linen textiles appear to be some of the oldest in the world; their history goes back many thousands of years. Dyed flax fibers found in a cave in Southeastern Europe (present-day Georgia) suggest the use of woven linen fabrics from wild flax may date back over 30,000 years.[2][3] Linen was used in ancient civilizations including Mesopotamia[4] and ancient Egypt.[5][6] There are many references to linen throughout the Bible, reflecting the textile's entrenched presence in human cultures.[7] In the 18th century and beyond, the linen industry was important in the economies of several countries in Europe[8][9][10] as well as the American colonies.[11]

Textiles in a linen weave texture, even when made of cotton, hemp, or other non-flax fibers, are also loosely referred to as "linen."

Etymology

The word linen is of West Germanic origin[12] and cognate to the Latin name for the flax plant, linum, and the earlier Greek λινόν (linón).

This word history has given rise to a number of other terms in English, most notably line, from the use of a linen (flax) thread to determine a straight line. It is also etymologically related to a number of other terms, including lining, because linen was often used to create an inner layer for clothing,[13] and lingerie, from French, which originally denoted underwear made of linen.[14]

History

People in various parts of the world began weaving linen at least several thousand years ago.[15]

Early history

The discovery of dyed flax fibers in a cave in Georgia dated to 36,000 years ago suggests that ancient people used wild flax fibers to create linen-like fabrics from an early date.[2][3]

Fragments of straw, seeds, fibers, yarns, and various types of fabrics, including linen samples, dating to about 8,000 BC have been found in Swiss lake dwellings.[10]

In ancient Mesopotamia, flax was domesticated and linen was produced.[16] It was used mainly by the wealthier class of the society, including priests. The Sumerian poem of the courtship of Inanna and Dumuzi (Tammuz), translated by Samuel Noah Kramer and Diane Wolkstein and published in 1983, mentions flax and linen. It opens with briefly listing the steps of preparing linen from flax, in a form of questions and answers between Inanna and her brother Utu.

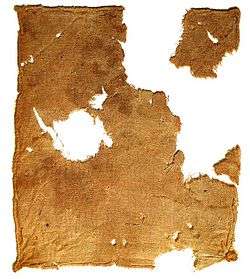

In ancient Egypt, linen was used for mummification and for burial shrouds. It was also worn as clothing on a daily basis; white linen was worn because of the extreme heat. For example, the Tarkhan dress, considered to be among the oldest woven garments in the world and dated to between 3482 and 3102 BC, is made of linen.[5] Plutarch wrote that the priests of Isis also wore linen because of its purity.[17][6] Linen was sometimes used as a form of currency in ancient Egypt. Egyptian mummies were wrapped in linen as a symbol of light and purity, and as a display of wealth. Some of these fabrics, woven from hand-spun yarns, were very fine for their day, but are coarse compared to modern linen.[18] When the tomb of the Pharaoh Ramses II, who died in 1213 BC, was discovered in 1881, the linen wrappings were in a state of perfect preservation after more than 3000 years. When the tomb of Tutankhamen was opened, the linen curtains were found to be intact. In the Ulster Museum, Belfast there is the mummy of 'Takabuti' the daughter of a priest of Amun, who died 2,500 years ago.[19] The linen on this mummy is also in a perfect state of preservation.

The earliest written documentation of a linen industry comes from the Linear B tablets of Pylos, Greece, where linen is depicted as an ideogram and also written as "li-no" (Greek: λίνον, linon), and the female linen workers are cataloged as "li-ne-ya" (λίνεια, lineia).[20][21]

Middle Ages

By the Middle Ages, there was a thriving trade in German flax and linen. The trade spread throughout Germany by the 9th century and spread to Flanders and Brabant by the 11th century. The Lower Rhine was a center of linen making in the Middle Ages.[22] Flax was cultivated and linen used for clothing in Ireland by the 11th century.[23] Evidence suggests that flax may have been grown and sold in Southern England in the 12th and 13th centuries.[24]

Textiles, primarily linen and wool, were produced in decentralized home weaving mills.[25]

Modern history

Linen continued to be valued for garments in the 16th century[26] and beyond. Specimens of linen garments worn by historical figures have survived. For example, a linen cap worn by Emperor Charles V was carefully preserved after his death in 1558.[26]

There is a long history of the production of linen in Ireland. When the Edict of Nantes was revoked in 1685, many of the Huguenots who fled France settled in the British Isles and elsewhere. They brought improved methods for linen production with them, contributing to the growth of the linen industry in Ireland in particular.[27] Among them was Louis Crommelin, a leader who was appointed overseer of the royal linen manufacture of Ireland. He settled in the town of Lisburn near Belfast, which is itself perhaps the most famous linen producing center throughout history; during the Victorian era the majority of the world's linen was produced in the city which gained it the name Linenopolis.[28] Although the linen industry was already established in Ulster, Louis Crommelin found scope for improvement in weaving, and his efforts were so successful that he was appointed by the Government to develop the industry over a much wider range than the small confines of Lisburn and its surroundings. The direct result of his good work was the establishment, under statute, of the Board of Trustees of the Linen Manufacturers of Ireland in the year 1711. Several grades were produced including coarse lockram. The Living Linen Project was set up in 1995 as an oral archive of the knowledge of the Irish linen industry, which was at that time still available within a nucleus of people who formerly worked in the industry in Ulster.

The linen industry was increasingly critical in the economies of Europe[8][9] in the 18th and 19th centuries. In England and then in Germany, industrialization and machine production replaced manual work and production moved from the home to new factories.[25]

Linen was also an important product in the American colonies, where it was brought over with the first settlers and became the most commonly used fabric and a valuable asset for colonial households.[11] Through the 1830s, most farmers in the northern United States continued to grow flax for linen to be used for the family's clothing.[29]

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, linen was very significant to Russia and its economy. At one time it was the country's greatest export item and Russia produced about 80% of the world's fiber flax crop.[10]

In December 2006, the General Assembly of the United Nations proclaimed 2009 to be the International Year of Natural Fibres in order to raise people's awareness of linen and other natural fibers.[1]

Religion

In Judaism, the only law concerning which fabrics may be interwoven together in clothing concerns the mixture of linen and wool, called shaatnez; it is restricted in Deuteronomy 22:11 "Thou shalt not wear a mingled stuff, wool and linen together" and Leviticus 19:19, "...neither shall there come upon thee a garment of two kinds of stuff mingled together." There is no explanation for this in the Torah itself and it is categorized as a type of law known as chukim, a statute beyond man's ability to comprehend.[30] First-century Romano-Jewish historian Josephus suggested that the reason for the prohibition was to keep the laity from wearing the official garb of the priests,[31][32] while medieval Sephardic Jewish philosopher Maimonides thought that the reason was because heathen priests wore such mixed garments.[33] Others explain that it is because God often forbids mixtures of disparate kinds, not designed by God to be compatible in a certain way, with mixing animal and vegetable fibers being similar to having two different types of plowing animals yoked together; also, such commands serve both a practical as well as allegorical purpose, perhaps here preventing a priestly garment that would cause discomfort (or excessive sweat) in a hot climate.[34]

Linen is also mentioned in the Bible in Proverbs 31, a passage describing a noble wife. Proverbs 31:22 says, "She makes coverings for her bed; she is clothed in fine linen and purple." Fine white linen is also worn by angels in the New Testament (Revelation 15:6).

Uses

Many products can be made with linen: aprons, bags, towels (swimming, bath, beach, body and wash towels), napkins, bed linens, tablecloths, runners, chair covers, and men's and women's wear.

Today, linen is usually an expensive textile produced in relatively small quantities. It has a long staple (individual fiber length) relative to cotton and other natural fibers.[35]

Linen fabric has been used for table coverings, bed coverings and clothing for centuries. The significant cost of linen derives not only from the difficulty of working with the thread, but also because the flax plant itself requires a great deal of attention. In addition flax thread is not elastic, and therefore it is difficult to weave without breaking threads. Thus linen is considerably more expensive to manufacture than cotton.

The collective term "linens" is still often used generically to describe a class of woven or knitted bed, bath, table and kitchen textiles traditionally made of flax-based linen but today made from a variety of fibers. The term "linens" refers to lightweight undergarments such as shirts, chemises, waist-shirts, lingerie (a cognate with linen), and detachable shirt collars and cuffs, all of which were historically made almost exclusively out of linen. The inner layer of fine composite cloth garments (as for example dress jackets) was traditionally made of linen, hence the word lining.[36]

Over the past 30 years the end use for linen has changed dramatically. Approximately 70% of linen production in the 1990s was for apparel textiles, whereas in the 1970s only about 5% was used for fashion fabrics.

Linen uses range across bed and bath fabrics (tablecloths, bath towels, dish towels, bed sheets); home and commercial furnishing items (wallpaper/wall coverings, upholstery, window treatments); apparel items (suits, dresses, skirts, shirts); and industrial products (luggage, canvases, sewing thread).[35] It was once the preferred yarn for handsewing the uppers of moccasin-style shoes (loafers), but has been replaced by synthetics.

A linen handkerchief, pressed and folded to display the corners, was a standard decoration of a well-dressed man's suit during most of the first part of the 20th century.

Currently researchers are working on a cotton/flax blend to create new yarns which will improve the feel of denim during hot and humid weather.[37] Conversely, some brands such as 100% Capri specially treat the linen to look like denim.[38]

Linen fabric is one of the preferred traditional supports for oil painting. In the United States cotton is popularly used instead, as linen is many times more expensive there, restricting its use to professional painters. In Europe, however, linen is usually the only fabric support available in art shops; in the UK both are freely available with cotton being cheaper. Linen is preferred to cotton for its strength, durability and archival integrity.

Linen is also used extensively by artisan bakers. Known as a couche, the flax cloth is used to hold the dough into shape while in the final rise, just before baking. The couche is heavily dusted with flour which is rubbed into the pores of the fabric. Then the shaped dough is placed on the couche. The floured couche makes a "non stick" surface to hold the dough. Then ridges are formed in the couche to keep the dough from spreading.

In the past, linen was also used for books (the only surviving example of which is the Liber Linteus). Due to its strength, in the Middle Ages linen was used for shields, gambesons, and bowstrings; in classical antiquity it was used to make a type of body armour, referred to as a linothorax.

Because of its strength when wet, Irish linen is a very popular wrap of pool/billiard cues, due to its absorption of sweat from hands.

In 1923, the German city Bielefeld issued banknotes printed on linen.[39] United States currency paper is made from 25% linen and 75% cotton.[40]

Flax fiber

Description

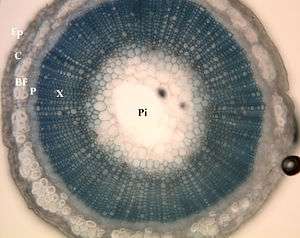

Linen is a bast fiber. Flax fibers vary in length from about 25 to 150 mm (1 to 6 in) and average 12–16 micrometers in diameter. There are two varieties: shorter tow fibers used for coarser fabrics and longer line fibers used for finer fabrics. Flax fibers can usually be identified by their “nodes” which add to the flexibility and texture of the fabric.

The cross-section of the linen fiber is made up of irregular polygonal shapes which contribute to the coarse texture of the fabric.[41]

Properties

Linen fabric feels cool to touch, a phenomenon which indicates its higher conductivity (the same principle that makes metals feel "cold"). It is smooth, making the finished fabric lint-free, and gets softer the more it is washed. However, constant creasing in the same place in sharp folds will tend to break the linen threads. This wear can show up in collars, hems, and any area that is iron creased during laundering. Linen's poor elasticity means that it easily wrinkles.

Mildew, perspiration, and bleach can damage the fabric, but because it is not made from animal fibers (keratin) it is impervious to clothes moths and carpet beetles. Linen is relatively easy to take care of, since it resists dirt and stains, has no lint or pilling tendency, and can be dry-cleaned, machine-washed, or steamed. It can withstand high temperatures, and has only moderate initial shrinkage.[41]

Linen should not be dried too much by tumble drying, and it is much easier to iron when damp. Linen wrinkles very easily, and thus some more formal garments require ironing often, in order to maintain perfect smoothness. Nevertheless, the tendency to wrinkle is often considered part of linen's particular "charm", and many modern linen garments are designed to be air-dried on a good clothes hanger and worn without the necessity of ironing.

A characteristic often associated with linen yarn is the presence of slubs, or small, soft, irregular lumps, which occur randomly along its length. In the past, slubs were traditionally considered to be defects, and were associated with low quality linen. However, in the case of many present-day linen fabrics, particularly in the decorative furnishing industry, slubs are considered as part of the aesthetic appeal of an expensive natural product. In addition, slubs do not compromise the integrity of the fabric, and therefore they are not viewed as a defect. However, the very finest linen has very consistent diameter threads, with no slubs at all.

Linen can degrade in a few weeks when buried in soil. Linen is more biodegradable than cotton.[42]

Measure

The standard measure of bulk linen yarn is the "lea", which is the number of yards in a pound of linen divided by 300. For example, a yarn having a size of 1 lea will give 300 yards per pound. The fine yarns used in handkerchiefs, etc. might be 40 lea, and give 40x300 = 12,000 yards per pound. This is a specific length therefore an indirect measurement of the fineness of the linen, i.e., the number of length units per unit mass. The symbol is NeL.(3) The metric unit, Nm, is more commonly used in continental Europe. This is the number of 1,000 m lengths per kilogram. In China, the English Cotton system unit, NeC, is common. This is the number of 840 yard lengths in a pound.

Production method

Linen is laborious to manufacture.[43]

The quality of the finished linen product is often dependent upon growing conditions and harvesting techniques. To generate the longest possible fibers, flax is either hand-harvested by pulling up the entire plant or stalks are cut very close to the root. After harvesting, the plants are dried, and the seeds are removed through a mechanized process called “rippling” (threshing) and winnowing.

The fibers must then be loosened from the stalk. This is achieved through retting. This is a process which uses bacteria to decompose the pectin that binds the fibers together. Natural retting methods take place in tanks and pools, or directly in the fields. There are also chemical retting methods; these are faster, but are typically more harmful to the environment and to the fibers themselves.

After retting, the stalks are ready for scutching, which takes place between August and December. Scutching removes the woody portion of the stalks by crushing them between two metal rollers, so that the parts of the stalk can be separated. The fibers are removed and the other parts such as linseed, shive, and tow are set aside for other uses. Next the fibers are heckled: the short fibers are separated with heckling combs by 'combing' them away, to leave behind only the long, soft flax fibers.

After the fibers have been separated and processed, they are typically spun into yarns and woven or knit into linen textiles. These textiles can then be bleached, dyed, printed on, or finished with a number of treatments or coatings.[41]

An alternate production method is known as “cottonizing” which is quicker and requires less equipment. The flax stalks are processed using traditional cotton machinery; however, the finished fibers often lose the characteristic linen look.

Producers

Flax is grown in many parts of the world, but top quality flax is primarily grown in Western European countries and Ukraine. In recent years bulk linen production has moved to Eastern Europe and China, but high quality fabrics are still confined to niche producers in Ireland, Italy and Belgium, and also in countries including Poland, Austria, France, Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Belarus, Lithuania, Latvia, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, Britain and Kochi in India. High quality linen fabrics are now produced in the United States for the upholstery market and in Belgium.

In 2018, according to the United Nations' repository of official international trade statistics, China was the top exporter of woven linen fabrics by trade value, with a reported $732.3 million in exports; Italy ($173.0 million), Belgium ($68.9 million) and the United Kingdom ($51.7 million) were also major exporters.[44]

See also

- Dowlas, a strong linen mentioned by Shakespeare

- Linenize

- Ramie, another type of bast fiber with similar properties

- Madapollam, a fabric manufactured from cotton yarn in a linen-style weave

- Belgian Linen, a type of linen known for its very high quality

References

- "Profiles of 15 of the world's major plant and animal fibres". International Year of Natural Fibres 2009. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Balter, M (2009). "Clothes Make the (Hu) Man". Science. 325 (5946): 1329. doi:10.1126/science.325_1329a. PMID 19745126.

- Kvavadze, E; Bar-Yosef, O; Belfer-Cohen, A; Boaretto, E; Jakeli, N; Matskevich, Z; Meshveliani, T (2009). "30,000-Year-Old Wild Flax Fibers". Science. 325 (5946): 1359. Bibcode:2009Sci...325.1359K. doi:10.1126/science.1175404. PMID 19745144.

- McCorriston, Joy (1997). "Textile Extensification, Alienation, and Social Stratification in Ancient Mesopotamia". Current Anthropology. 38 (4): 517–535. doi:10.1086/204643. JSTOR 10.1086/204643.

- Lobell, Jarretta (2016). "Dressing for the Ages". Archeology. 69 (3): 9. ISSN 0003-8113.

- Warden, Alex. J. (1867). The linen trade, ancient and modern (2nd ed.). Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green. p. 214. hdl:2027/hvd.32044019641166.

- "What Is Linen? Everything You Need to Know About Using and Caring for Linen". MasterClass. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Takei, Akihiro (1994). "The First Irish Linen Mills, 1800–1824". Irish Economic and Social History. 21: 28–38. doi:10.1177/033248939402100102. JSTOR 24341383.

- Belfanti, Marco (2006). "Reviewed Work: The European Linen Industry in Historical Perspective by Brenda Collins, Philip Ollerenshaw". Technology and Culture. 47 (1): 193–195. doi:10.1353/tech.2006.0056. JSTOR 40061028. S2CID 108825085.

- Akin, Danny E. (30 December 2012). "Linen Most Useful: Perspectives on Structure, Chemistry, and Enzymes for Retting Flax". ISRN Biotechnology. 2013: 186534. doi:10.5402/2013/186534. PMC 4403609. PMID 25969769.

- Keegan, Tracy A. (1996). "Flaxen fantasy: the history of linen". Colonial Homes. 22 (4): 62+. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- "linen". Lexico.com. Oxford. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Harper, Douglas. "line". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 2018-01-26. Retrieved 2018-01-25.

- Harper, Douglas. "lingerie (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- Beckert, Sven (2014). Empire of Cotton. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 5. ISBN 978-0375414145.

- Potts, Daniel T. (1997). Mesopotamian Civilization: The Material Foundations. The Athlone Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-485-93001-3.

- Plutarch (1940). Babbitt, Frank Cole (ed.). "Isis and Osiris". Nature. 146 (3695): 262. Bibcode:1940Natur.146U.262.. doi:10.1038/146262e0. S2CID 4092286. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Harris, Thaddeus Mason (1824). The natural history of the Bible; or, A description of all the quadrupeds, birds, fishes [&c.] mentioned in the Sacred scriptures. p. 135. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- "Takabuti the ancient Egyptian mummy" - Ulster Museum, Egyptian Gallery

- Flax and Linen Textiles in the Mycenaean palatial economy Archived 2008-04-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Robkin, A. L. H. (1 January 1979). "The Agricultural Year, the Commodity SA and the Linen Industry of Mycenaean Pylos". American Journal of Archaeology. 83 (4): 469–474. doi:10.2307/504148. JSTOR 504148.

- Keller, Kenneth W. (1990). "From the Rhineland to the Virginia Frontier: Flax Production as a Commercial Enterprise". The Virginia Backcountry. 98 (3): 488. JSTOR 4249165.

- "Flax to Fabric: The Story of Irish Linen". Irish Linen Centre & Lisburn Museum. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Collins, Brenda (1998). "Linen in Europe Conference 16–19 April 1998 Irish Linen Centre & Lisburn Museum". Irish Economic and Social History. 25: 96–99. doi:10.1177/033248939802500109. JSTOR 24341023.

- "The Development of Textile Technology: Inside the TextilTechnikum (Textile Technology Center) in Monforts Quartier, Mönchengladbach". Google Arts & Culture. Textiltechnikum. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Pollen, John Hungerford (1914). "Ancient Linen Garments". The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs. 25 (136): 231–237. JSTOR 859719.

- Lutton, S.C. "Background history of Linen from the flax in the field to finished linen cloth". Journal of Craigavon Historical Society. 8 (1). Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Prance, Sir Ghillean (2012). The Cultural History of Plants. Routledge. p. 295. ISBN 9781135958114.

- Wyatt, Steve M. (1994). "Flax and Linen: An Uncertain Oregon Industry". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 95 (2): 150–175. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- The Jewish Primer, by Shmuel Himelstein. New York, NY: Facts On File, 1990.

- Etz Hayim p. 1118

- Josephus. "8.11". Antiquities of the Jews. Translated by Whiston.

- Guide for the Perplexed 3:37

- Jamieson, Fausset, Brown commentary, Lv. 19:19

- Textiles, Ninth Edition by Sara J. Kadolph and Anna L. Langford. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall

- lining. Dictionary.com. Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper, Historian. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2014-10-04.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) (accessed: October 3, 2014).

- "Flax Fiber Offers Cotton Cool Comfort". Agricultural Research. November 2005.

- "Just add water". Miami Herald. 5 June 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- Walter Grasser / Albert Pick (1972). Das Bielefelder Stoffgeld 1917-1923. Berlin, Germany: Erich Pröh.

- "U.S. Currency". Bureau of Engraving and Printing. U.S. Department of the Treasury. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Classifications & Analysis of Textiles: A Handbook by Karen L. LaBat, Ph.D. and Carol J. Salusso, Ph.A. University of Minnesota, 2003

- Arnett, George. "How quickly do fashion materials biodegrade?". Vogue Business. Conde Nast. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- Hakoo, Ashok. "Linen Fiber and Linen Fabrics from the Flax Plants". TextileSchool. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- "5309 - Woven fabrics of flax". UN Comtrade Database. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Linen (flax). |

| Look up linen in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1921 Collier's Encyclopedia article Linen. |

.svg.png)