Zheng Zhilong

Zheng Zhilong, Marquis of Tong'an and Nan'an (Chinese: 鄭芝龍; pinyin: Zheng Zhilong; Wade–Giles: Ching Chih-lung; 1604–1661), baptised as Nicholas Iquan Gaspard,[2] was a merchant, pirate, political and military leader in the late Ming dynasty who later defected to the Qing dynasty. He was from Nan'an, Fujian.[3] He was the father of Koxinga, Prince of Yanping, the founder of the pro-Ming Kingdom of Tungning in Taiwan, and as such an ancestor of the House of Koxinga. After his defection, he was given noble titles by the Qing government, but was eventually executed because of his son's continued resistance against the Qing regime.

| Zheng Zhilong 鄭芝龍 | |

|---|---|

| Marquis of Tong'an Marquis of Nan'an Count of Nan'an | |

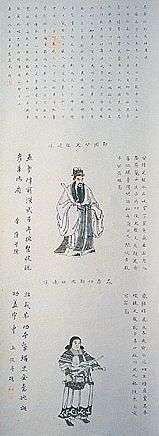

Illustration of Zheng Zhilong and his son Koxinga, Prince of Yanping | |

| Born | 1604 Nan'an, Fujian, Ming dynasty, China |

| Died | 1661 (aged 56–57) Beijing, Qing dynasty, China |

| Wives | Tagawa Matsu Lady Yan[1] |

| Issue | Koxinga, Prince of Yanping Shichizaemon Tagawa Zheng Xi |

| Royal house | The House of Koxinga |

| Father | Zheng Shaozu |

| Mother | Lady Wang |

| Religion | Catholic, Mazu (goddess), Marici (Buddhism) |

| Occupation | Political figure, merchant-mandarin and pirate |

| Zheng Zhilong | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 鄭芝龍 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 郑芝龙 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||

| Kanji | 鄭 芝龍 | ||||||||

| Kana | ジェン・ジーロン | ||||||||

| Hiragana | てい しりゅう | ||||||||

| |||||||||

History

Early life

Zheng was born in Fujian, the son of Zheng Shaozu (鄭紹祖), a mid-level financial official for the Quanzhou government and Zheng Shaozu's wife Lady Huang (黃氏). Just like other typical Zheng clans in Fujian, Zheng Zhilong's ancestors originated in Northern China but due to the Uprising of the Five Barbarians and Disaster of Yongjia by the Five Barbarians, the Zheng family were among the northern refugees who fled to Southeastern China and settled in Fujian. They later moved to Zhangzhou and moved on to Nan'an.[4][5] Between 1144 and 1210 Zheng Zhilong's ancestors moved to Longxi county and moved on to Nan'an. Between 1144 and 1210, Zheng Chenggong's ancestor Zheng Boke moved from Qiangtian to Longbei County's Jubei Village (now Longhai Bangshan Town) and his second son was in the early years of the Yuan Dynasty. He came to Zhangzhou from the north and opened in Gugu County. Ji Liye is the ancestor of the Longshan Zheng. There is a passage in the Zheng genealogy contained in the Selected Works of Genealogical Data of Fujian and Taiwan Relations, indicating that Zheng's entry into the shackles, "or in Sanshan, Yusong. Yu Chao, is not one place." Among them, the one that arrived in Zhangzhou lived in Longxi at the end of the Song Dynasty, which is now the Yangxi Village of Bangshan Town, Longhai. In the Yuan Dynasty, it was moved from Yangxi to Lushan, which is now the Fujian Longhai Yanyan. Zhengu County. Subsequently, it was moved from the ancient county to Nan'an. The epitaph of the 13th ancestor of the Anping Zheng of Jinjiang was written by Hong Chengchou, the governor of the Ming Dynasty. Hong Chengchou stated in the epitaph of Zheng Chenggong: "Zheng Zhijin was also the first to visit the Fengting Pavilion of Xianyou, the hometown of migration and climbing scales. There is Fengting Bridge garbage, and today its name still exists in the beginning of the ancestors of the ancestors and the number is passed down to the nickname Guo Zhaisheng. The epitaph also mentioned that due to frequent violations, it was forced to move south to the Anping area of Jinjiang, which is now the Anhai area.

Contemporary biographies tell a possibly apocryphal story of how when Zheng was a child, he and his brothers wanted to eat longan fruit.[3] They found a fruit tree in an enclosed courtyard but whose branches hung over the top of the wall into the street. They threw stones in the hope of knocking some of the fruit clusters loose.[3] It happened to be the courtyard of the governor of Quanzhou City and he was struck by the stones. The boys ran but were caught and hauled before the governor. Due to the child's age and apparent charisma, the governor forgave Zheng and released him, saying "This is the face of one destined for wealth and nobility."[3] The story may or may not be true, but it encapsulated the character of Zheng: he ran wild, grasped at low hanging fruit, got in trouble and came out the better for it.[3] Accounts vary as to the year of his birth. One gives it as 1595, others as 1604 or in between those years like 1600.[6] Most agree he was born in 1604.

Zheng was said to be "very good looking" and when he first came to Japan he was 18 years old.[7][8][9]

Zheng left home as a teenager, jumping aboard a merchant ship. Sources vary on why he left home, some saying he slipped his hand up the skirt of one of his father's concubines, others recording his father chasing him through the streets with a stick.[3] Zheng went to Macau where his mother's brother lived (his uncle).[3] The story of him trying to touch his father's concubine is deemed to be "implausible", with it more likely he ran away because he wanted to or his father kicked him out for delinquent behavior like his tendency to engage in constant fighting and vandalism in public.[10] He was baptized as a Catholic in Macau, receiving the Christian name Nicholas Gaspard.[11][12][13] His uncle asked him to take some cargo to Nagasaki, Japan, where he met a rich old Min man named Li Dan, the Japanese city's Kapitan Cina or Chinese headman, who became his mentor and possible lover.[3] Li Dan had close ties with the Europeans and he arranged for Zheng to work as an interpreter for the Dutch (Zheng spoke Portuguese which the Dutch could also speak).[3][14][15] Zheng spoke Portuguese, Chinese and Japanese.[16] In 1622, when Dutch forces took over the Pescadores archipelago off the Taiwan Strait, Li Dan sent Zheng to the Pescadores to work with the Dutch as a translator in peace negotiations during the war between the Ming and Dutch over the islands.[17] Before leaving Japan, he met and married a local Japanese woman named Tagawa Matsu.[3] He impregnated her with Zheng Chenggong (Koxinga), leaving Japan before she gave birth in 1624.[3][18] The terms 合巹 and 隔冬 are used to describe his marriage to Tagawa Matsu in the Taiwan Waiji while the term 割同 was used by Foccardi.[19]

The group of traders working with the Kapitan Cina wanted to arrange for a fellow Chinese woman, Lady Yan to marry Zheng Zhilong.[20]

Zheng Zhilong allegedly had an unknown daughter with another Japanese woman who was not Tagawa Matsu but this is only mentioned by one writer, Palafox who is very unreliable.[21] This alleged daughter was supposedly among the Japanese who converted to Christianity.[22] The alleged daughter was mentioned in "history of the Conquest of China" by Palafox while Japanese and Chinese accounts make zero mention of any daughter who could hardly have been ignored while reaching her teenager years.[23] It is more likely that the Kapitan Cina's daughter Elizabeth could be this alleged daughter of Zheng Zhilong by the mystery Japanese woman, if she was even a real person in the first place.[24]

After Li died in 1625, Zheng acquired his fleet.

Pirate

The Dutch East India Company, also called the VOC, wished to gain free trade rights with China and to control and commerce routes to Japan. To accomplish these goals, they collaborated with some Chinese pirates to pressure the Ming Dynasty in China to allow trade.[25] Zheng Zhilong initially worked as a translator, although there is debate if he was engaging pirate activities simultaneously. Regardless, most scholars agree that he joined with other Chinese pirates, probably Li Dan or Yan Siqi. In 1624, Zheng officially became a privateer for the Dutch East India Company after they colonized Taiwan. During this time, he was still aligned with Li Dan. The Dutch did not like how powerful Li Dan was becoming, so they used Zheng Zhilong to weaken Li Dan's position. However, Li Dan died before they could fully complete their plan. With Li Dan dead, Zheng Zhilong became the unopposed leader of the Chinese pirates.[2]

Following his ascension to power, began to build up his fleets. With access to European sailing and military technology he made his armada of junks superior to the Chinese Imperial navy.[26] Zheng prospered and by 1627 he was leading four hundred junks and tens of thousands of men, including Chinese, Japanese, and even some Europeans.[3][27] He had a bodyguard of former black slaves who ran away from the Portuguese.[28][29] By 1630, he controlled all shipping in the South China Sea.

In addition to attacking shipping in the South China Sea, Zhen Zhilong also increased his power by selling protection passes to fisherman and merchants. At the height of his power, no one dared sail without one of his passes for fear of retribution.[30] However, he was not universally hated. He was actually loved by many peasants in the southern provinces of China. He earned their respect by refraining from unnecessary attacks on their towns and giving some stolen grain to them during famines.[26] He also gave unemployed fisherman and sailors jobs in his vast fleet.[27]

Shibazhi challenges the Ming fleet

Shibazhi (十八芝) were a pirate organization of 18 well-known Chinese pirates, founded in 1625 by Zheng Zhilong. Members included Shi Lang's father Shi Daxuan (施大瑄). They began to challenge the Ming fleet and won a series of victories. In 1628, Zheng Zhilong defeated the Ming Dynasty's fleet. The Ming Dynasty's southern fleet surrendered to Shibazhi, and Zheng decided to switch from being a pirate captain to working for the Ming Dynasty in an official capacity.[3] Zheng Zhilong was appointed major general in 1628. Stories tell of how Cai, the governor who had forgiven Zheng for stoning him so many years ago, came to Zheng and asked for a position in the Ming navy. Zheng granted this request. Whether or not this story is true is unknown, but it reflects the popular appraisal of Zheng who was seen as a benevolent leader.

Service under the Ming

After joining the Ming navy, Zheng and his wife resettled on an island off the coast of Fujian, where he operated a large armed pirate fleet of over 800 ships along the coast from Japan to Vietnam. He was appointed by the Chinese Imperial family as "Admiral of the Coastal Seas". In this capacity he defeated an alliance of Dutch East India Company vessels and junks under renegade Shibazhi pirate Liu Xiang (劉香) on October 22, 1633 in the Battle of Liaoluo Bay. The spoils that followed from this victory made him fabulously wealthy. He bought a large amount of land (as much as 60% of Fujian), and became a powerful landlord.

Zheng would continue to serve the Ming dynasty after the fall of the Ming capital Beijing in June 1644. His brother Zheng Zhifeng was made a marquis under the Southern Ming, although he was forced to abandon his post at Zhenjiang by a superior Qing force. After the capture of Nanjing in 1645, Zheng accepted an offer to serve as commander-in-chief of the imperial forces and was ordered to defend the newly established capital in Fuzhou under the Prince of Tang.

Surrender to Qing

In 1646, Zheng decided to defect to the Manchus leaving the passes of Zhejiang unguarded, allowing Manchu forces to capture Fuzhou. His defection was facilitated by Tong Guozhen and Tong Guoqi.[31] His brothers who still controlled most of the Zheng army, and his son Koxinga refused to defect to the Qing and asked him to not surrender. Zheng Zhilong did not listen and the Qing noticed his followers and army had not followed him in his defection, so he was placed under house arrest and taken to Beijing. His bodyguard of former African slaves all died trying to stop the arrest and protect their master.

The Qing then marched to one of his castles in Anhai to humiliate his Japanese wife Tagawa Matsu. Different accounts say that Tagawa was raped by Qing forces and then committed suicide or that she committed suicide while directing the fight against the Qing. The Qing did not trust Zheng afterwards due to their role in Tagawa's death.[32]

Zheng Zhilong, along with his servants and sons who went with him were kept under house arrest for many years, until 1661. The Qing initially sentenced Zheng and his remaining servants and sons with him to death by lingchi but commuted their sentence to death by decapitation instead. He would later be executed by the Qing government in 1661 at Caishikou,[33] as a result of his son Koxinga's continued resistance against the Qing regime.

References

Citations

- Jonathan Clements (24 October 2011). Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7382-6.

- Cheng, Weichung (2014). War, Trade and Piracy in the China Seas, (1622-1683). Brill. pp. 37–39, 41.

- Andrade, Tonio (2011). Lost colony : the untold story of China's first great victory over the West. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691144559.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- 福建人民出版社《闽台关系族谱资料选编》

- 台湾《漳龙衍派鄱山氏之来龙去脉》( 在2002年举行的纪念郑成功收复台湾340周年研讨会上 郑姓)

- Sazvar, Nastaran. “ZHENG CHENGGONG (1624-1662): EIN HELD IM WANDEL DER ZEIT: DIE VERZERRUNG EINER HISTORISCHEN FIGUR DURCH MYTHISCHE VERKLÄRUNG UND POLITISCHE INSTRUMENTALISIERUNG.” Monumenta Serica, vol. 58, 2010, pp. 160. JSTOR, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41417880?seq=8#page_scan_tab_contents.

- Matsuda Wataru (13 September 2013). Japan and China: Mutual Representations in the Modern Era. Routledge. pp. 191–. ISBN 978-1-136-82109-7.

- NA NA (30 April 2016). Japan and China: Mutual Representations in the Modern Era. Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 191–. ISBN 978-1-137-08365-4.

- Sino-Japanese Studies. Sino-Japanese Studies Group. 1993. p. 21.

- Xing Hang (5 January 2016). Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720. Cambridge University Press. pp. 42–. ISBN 978-1-316-45384-1.

- "Zheng Zhilong". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2011.

- Ferdinand Edralin Marcos (1977). Tadhana: The formation of the national community (1565-1896). 2 v. Marcos. p. 23.

- Jonathan Clements (24 October 2011). Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7382-6.

- Jonathan Clements (24 October 2011). Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7382-6.

- Xing Hang (5 January 2016). Conflict and Commerce in Maritime East Asia: The Zheng Family and the Shaping of the Modern World, c.1620–1720. Cambridge University Press. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-1-316-45384-1.

- James Albert Michener; Arthur Grove Day (2016). Rascals in Paradise. Dial Press. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-0-8129-8686-0.

- Jonathan Clements (24 October 2011). Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7382-6.

- Marius B. Jansen; Professor Marius B Jansen (1992). China in the Tokugawa World. Harvard University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-674-11753-2.

- Sazvar, Nastaran. “ZHENG CHENGGONG (1624-1662): EIN HELD IM WANDEL DER ZEIT: DIE VERZERRUNG EINER HISTORISCHEN FIGUR DURCH MYTHISCHE VERKLÄRUNG UND POLITISCHE INSTRUMENTALISIERUNG.” Monumenta Serica, vol. 58, 2010, pp. 161. JSTOR, JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41417880?seq=9#page_scan_tab_contents.

- Jonathan Clements (24 October 2011). Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7382-6.

- Jonathan Clements (24 October 2011). Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7382-6.

- Jonathan Clements (24 October 2011). Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7382-6.

- Jonathan Clements (24 October 2011). Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7382-6.

- Jonathan Clements (24 October 2011). Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7382-6.

- "The Company's Chinese Pirates: How the Dutch East India Company Tried to Le...: EBSCOhost". eds.a.ebscohost.com. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- MacKay, Joseph (2013). "Pirate Nations: Maritime Pirates as Escape Societies in Late Imperial China". Social Science History. 37 (4): 551–573. doi:10.1215/01455532-2346888. JSTOR 24573942.

- Antony, Robert. "Elusive Pirates, Pervasive Smugglers: Violence and Clandestine Trade in the Greater China Seas". ebookcentral.proquest.com. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- Mateo, José Eugenio Borao (2009). The Spanish Experience in Taiwan 1626-1642: The Baroque Ending of a Renaissance Endeavour (illustrated ed.). Hong Kong University Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-9622090835.

- Ho, Dahpon David. Sealords live in vain : Fujian and the making of a maritime frontier in seventeenth-century China (A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Hi story). UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO.

- Antony, Robert (2007). Pirates in the Age of Sail. Norton & Company Inc. pp. 111–114.

- Frederic E. Wakeman (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China. University of California Press. pp. 1017–. ISBN 978-0-520-04804-1.

- Jonathan Clements (24 October 2011). Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty. History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-7382-6.

- 呂正理 (2010). 另眼看歷史(上):一部有關中、日、韓、台灣及周邊世界的多角互動歷史. p. 448. ISBN 978-9573266631.

Bibliography

- Clements, Jonathan (2004). Coxinga and the Fall of the Ming Dynasty. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 9780750932691. OCLC 232532621.

- Manthorpe, Jonathan (2005). Forbidden Nation: A History of Taiwan. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403969811. OCLC 58720732.

- Michael, Franz (1942). The Origin of Manchu Rule in China. Baltimore. OCLC 582266326.

- Andrade, Tonio (Dec 2004). "The Company's Chinese Pirates: How the Dutch East India Company Tried to Lead a Coalition of Pirates to War Against China, 1621-1662". Journal of World History. 15 (4): 415–444. doi:10.1353/jwh.2005.0124.