John Hawkins (naval commander)

Sir John Hawkins (also spelled Hawkyns) (1532 – 12 November 1595) was a pioneering English naval commander and administrator. He was also a privateer and an early promoter of English involvement in the Atlantic slave trade.

Sir John Hawkins | |

|---|---|

Portrait of John Hawkins at the National Maritime Museum, London | |

| Born | 1532 Plymouth, Devon, England |

| Died | 12 November 1595 (aged 62–63) off Puerto Rico, Spanish Main |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1562–1595 |

| Commands held | Treasurer of the Navy Admiral of the Narrow Seas |

| Battles/wars | Spanish Armada English Armada Battle of San Juan de Ulúa |

| Children | Richard Hawkins (1562–1622) |

His elder brother and trading partner was William (b. c.1519). He was considered the first English trader to profit from the Triangle Trade, based on selling supplies to colonies ill-supplied by their home countries, and their demand for African slaves in the Spanish colonies of Santo Domingo and Venezuela in the late 16th century. He styled himself "captain general" as the general of both his own flotilla of ships and those of the English Royal Navy, and to distinguish himself from those Admirals that served only in the administrative sense and were not military in nature. His death, and that of his second cousin and protégé, Sir Francis Drake, heralded the decline of the Royal Navy for decades before its recovery; its eventual resurgence helped by the tales of derring-do of the Navy's glory days under his leadership.

As Treasurer of the Navy (1577–1595) and Comptroller (1589) , Hawkins rebuilt older ships and directed design of faster ships that withstood the Spanish Armada in 1588. One of the foremost seamen of 16th-century England, Hawkins was the chief architect of the Elizabethan Navy. In the battle which defeated the Spanish Armada in 1588, Hawkins served as a Vice-Admiral. He was knighted for gallantry. He later devised the naval blockade that intercepted Spanish treasure ships leaving Mexico and South America.

Early years

John Hawkins was born to a prominent family in Plymouth in the county of Devon. His exact date of birth is unknown, but was likely between November 1532 and March 1533.[1] He was the second son of William Hawkins (b. before 1490, d. 1554/5) and Joan Trelawny, daughter and sole heiress of Roger Trelawny of Brighton, Cornwall.[2]

Hawkins is thought to have done some service as a young man for the ambassadors from Spain, who negotiated the marriage of Mary I of England and Philip II of Spain. The Spanish claim that Hawkins was personally knighted by the King for this service, which is as yet unconfirmed. Hawkins was known to have referred frequently to King Philip as "my old master". In fact, Hawkins was known as Juan Aquines by the Spaniards, who Castilianised the name, such was his fame among them.[2]

In 1555, John Lok employed five men from present-day Ghana and brought them back to England from a trading voyage to Guinea.[3][4]

First voyage (1562–1563)

Hawkins received commission from Queen Elizabeth I which allowed him to privateer. England was not at war with Spain, but the commission allowed Hawkins to plunder the Spanish fleet for loot.[5] Hawkins formed a syndicate of wealthy merchants to invest in trade. In 1562, he set sail with three ships to Sierra Leone where he captured 300 slaves, and took them to the plantations in the Americas where he traded the slaves for pearls, hides, and sugar.[5][6]

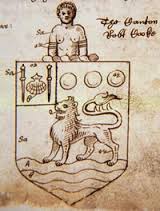

The trade was so prosperous that on his return to England the Crown supported additional voyages and granted Hawkins a coat of arms.[5]

Second voyage (1564–1565)

Source:[7]

The Spanish liked to keep a monopoly on trade, but Diego Ruiz de Vallejo, public accountant, allowed Hawkins to trade slaves on the condition he pay 7.5% of the Almojarifazgo tax. Alonzo Bernaldez, the Borburata governor, submitted a report in which the transaction was recorded as legitimate. After Hawkins traded at all Venezuelan ports and Rio de la Hacha, with advantageous returns, he was awarded a certificate of good behaviour. In summary, Hernando de Heredia, Rio de la Hacha public notary and councilman hereby stated:

During the course of the first 19 days of May, Sir Juan Haquines, commander of the English fleet stationed in Rio de la Hacha, carried out commercial operations with all residents by trading slaves and goods...

A commercial licence was extended to him on 21 May 1565 by honorable sir Rodrigo Caso, city regular mayor, Hernando Castilla, Miguel de Castellanos, treasurer, Lazaro de Vallejo Alderete, quartermaster, Baltasar de Castellanos and Domingo Felix, aldermen. During the same year, Audience of Santo Domingo initiated investigations leading to know about the irregular activities performed by Rio de la Hacha seniors officials who were involved in a deal with John Hawkins. Castellanos, the treasurer, was accused of having a fraudulent deal regarding to slave trade. It was the third time the English filibuster roamed about the area accomplishing large commercial operations among which the slave trade was significant. This fact was not overlooked by Santo Domingo Audience civil servants in connection to his visits to Venezuelan ports: In the year 65 [...] recorded in 1567 [...] there was such a coaster named Juan de Aquines, Englishman [...] with enough goods and 300 to 400 slaves product of his raids in Guinea territory [...] In the Province of Venezuela quite a few slaves and merchandise were rescued from this Englishman and others such as Frenchmen and Portuguese who were accustomed to this kind of activities....[8]

After completing his business, Hawkins prepared to return to England. Needing water, he sailed to the French colony of Fort Caroline in Florida. Finding them in need, he traded his smallest ship and a quantity of provisions to them for cannon, powder, and shot, that they no longer needed, as they were preparing to return to France. The provisions gained from Hawkins enabled the French to survive and prepare to move back home as soon as possible. As Laudonnière writes: "I may saye that wee receaved as manye courtesies of the Generall, as it was possible to receive of any man living. Wherein doubtlesse hee hath wonne the reputation of a good and charitable man, deserving to be esteemed as much of us all as if hee had saved all our lives."[9]

1570–1587

Hawkins's financial reforms of the Navy upset many who had vested interests. In 1582, his rival, Sir William Wynter, accused him of administrative malfeasance, instigating a Royal Commission on fraud against him. The commission, under William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, Francis Walsingham, and Drake, concluded that there was no corruption, and that the Queen's Navy was in first-rate condition.[10]

Spanish Armada

After the defeat of the Armada, Hawkins urged the seizure of Philip II's colonial treasure, in order to stop Spain re-arming. In 1589, Hawkins sailed with Francis Drake in a massive military operation (the Drake & Norris Expedition). One of its goals was to try to intercept the Spanish treasure ships departing from Mexico. One decisive action might have forced Philip II to the negotiating table and avoided fourteen years of continuing warfare. Instead, the voyage failed and the King was able to use the brief respite to rebuild his naval forces and, by the end of 1589, Spain once again had an Atlantic fleet strong enough to escort the American treasure ships home.[11]

Tobacco

Historians have noted that Hawkins and his crew were some of the first travellers from Europe to observe tobacco use in the Americas during their voyages in 1562. Sparke's chronicle of his second voyage recounts the inhabitants, of Fort Caroline in what is now north-east Florida, smoking tobacco leaves on approximately 20 July 1565: “The Floridians ... haue a kinde of herbe dryed1 [1 Tobacco.] which with a cane, and an earthen cup in the end, with fire, and the dried herbs put together do smoke thoro the cane the smoke thereof ... .”[12] He and his men brought back both the leaves and the practice of smoking to England in 1565, though the practice did not gain in popularity until years after.[13][14]

Final years and death

Hawkins son Richard was captured by the Spanish in 1593 in the South Atlantic. With Sir Francis Drake, he raised a fleet of 27 ships to attack the Spanish in the West Indies. They set sail from Plymouth on 29 August 1595. Bad weather and skirmishes with the Spanish fleet hampered their efforts to get his son back. On 12 November 1595, it was reported that Hawkins died at sea close to Puerto Rico.[5][15]

Memorials and reappraisal

The Royal Navy named a heavy cruiser HMS Hawkins after Hawkins; the ship was in commission from 1919 to 1947.[16]

The Hospital of Sir John Hawkins Knight in Chatham, Kent is named after Hawkins.[17] There was also a flyover in Chatham, which was demolished in 2008.[18] In June 2020, Plymouth City Council announced that due to Hawkins's links with the slave trade, it planned to rename Sir John Hawkins Square after footballer Jack Leslie, who was, during his time with Plymouth Argyle, the only black professional player in England.[19][20]

Links to the slave trade

Hawkins gained notice again in June 2006, more than four centuries after his death, when a supposed descendant, Andrew Hawkins, publicly apologised for John Hawkins's actions in the slave trade.[21] Andrew and 20 friends from the Christian charity Lifeline Expedition knelt in chains before 25,000 Africans to ask forgiveness for his ancestor's involvement in the slave trade at Independence Stadium in Bakau, the Gambia. The Vice-President of the Gambia Isatou Njie Saidy symbolically removed the chains in a spirit of reconciliation and forgiveness.[22][6]

Notes

- Kelsey 2003 p. 7

- Morgan 2004.

- The Slave Trade and Abolition: Timeline, English Heritage Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- Africans in British History Archived 2 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 28 November 2013/

- "John Hawkins – Admiral, Privateer, Slave Trader". Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Cacciottolo, Mario (23 June 2006). "My ancestor traded in human misery". BBC News. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- See the eyewitness account of this voyage by John Sparke, "The Voyage Made by the Worshipful M. John Haukins Esquire", pp. 523–43 in Richard Hakluyt, Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation (London: George Bishop and Ralph Newberie, 1589); 1906 repr. ed. by Henry S. Burrage, "The Voyage Made by M. John Hawkins Esquire, 1565" Archived 25 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 10 July 2016).

- Saignes, Miguel (1967). Vida de los esclavos negros en Venezuela. Hesperides. LCCN 68070476. p. 60

- René Goulaine de Laudonnière, A notable historie containing foure voyages made by certayne French captaynes vnto Florida (trans. Richard Hakluyt; London: Thomas Dawson, 1587), 51–52.

- Herman, Arthur (2004). To Rule the Waves: How the British Navy Shaped the Modern World. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-340-73419-1. p. 103

- The Mariner's mirror, Volumes 76–77. Society for Nautical Research., 1990

- John Sparke, "The Voyage Made by the Worshipful M. John Haukins Esquire," in Richard Hakluyt, Principall Navigations, Voiages and Discoveries of the English Nation (London: George Bishop and Ralph Newberie, 1589); repr. Hakluyt Society 58 (London: 1878); repr.Markham, Clements R. (2005). The Hawkins' Voyages During the Reigns of Henry VIII, Queen Elizabeth and James I. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1-4021-9536-2. p. 57. Cf. 1906 ed. by Henry S. Burrage, "The Voyage Made by M. John Hawkins Esquire, 1565" (Charles Scribner's Sons); accessed 10 July 2016. The date of 20 July is figured by the number of apparent days having lapsed following his recording on p. 49 the date of 12 July. Cf. also Gately, Iain (2001). Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization. Grove Press. ISBN 978-0802117052. p. 44.

- Stow, John (1615). Annales of England or a general Chronicle of England. pp. 806–07.

- Ley, Willy (December 1965). "The Healthfull Aromatick Herbe". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 88–98.

- "Sir John Hawkins". Britannica. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "HMS Hawkins – Hawkins-class Cruiser". Naval-History.net. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- "Hospital of Sir John Hawkins". housingcare.org. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "Flyover's demolition under fire". BBC News. 25 June 2008. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Ward, Victoria (19 June 2020). "Plymouth city square named after slave trader to be renamed after black footballer". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "Plymouth square to be renamed after black footballer Jack Leslie". BBC News. 18 June 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "The Times | UK News, World News and Opinion". Timesonline.co.uk. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- Hamilton, Alan (22 June 2006). "Slaver's descendant begs forgiveness". The Times. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

References

- Morgan, Basil (2004). "Hawkins, Sir John (1532–1595)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12672. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Attribution

![]()

Further reading

- Davis, Bertram. Proof of Eminence: The Life of Sir John Hawkins. Indiana University Press. 1973.

- Hazlewood, Nick. The Queen's Slave Trader: John Hawkyns, Elizabeth I, and the Trafficking in Human Souls. HarperCollins Books, New York, 2004. ISBN 0-06-621089-5.

- The African Slave Trade and Its Suppression: A Classified and Annotated Bibliography of Books, Pamphlets and Periodical Articles, annotated by Peter C. Hogg (editor), Frank Cass and Co. Ltd., Abingdon, Oxon, England; and Frank Cass and Co. Ltd., New York (1973), ISBN 0-7146-2775-5 . Transferred to Digital Printing 2006

- Kelsey, Harry. Sir John Hawkins, Queen Elizabeth´s Slave Trader, Yale University Press, 384 pages, (April 2003), ISBN 978-0-300-09663-7

- Southey, Robert. "Sir John Hawkins and Sir Francis Drake", pp. 67–242 of Vol. 3, The Lives of the British Admirals, 5 vols. 1833–1840.

- Unwin, Rayner. The Defeat of John Hawkins: A Biography of His Third Slaving Voyage. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd., 1960; New York: Macmillan, 1960.

- Walling, R.A.J. A Sea-Dog of Devon: a Life of Sir John Hawkins. 1907.

- Williamson, James. Hawkins of Plymouth: a new History of Sir John Hawkins. 1949. Second edition, 1969.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Hawkins (naval commander). |

- Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney, eds. (1891). . Dictionary of National Biography. 25. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 212–19.

- An exhibit in the National Archives of the United Kingdom

- "John Hawkins", Welbank.net

- "John Hawkins", Johntoddjr.com

- "John Hawkins", Tudorplace.com.ar

| Preceded by Benjamin Gonson |

Treasurer of the Navy 1577–1595 (jointly with Benjamin Gonson, 1577) |

Succeeded by Fulk Greville |