Skald

Skald, or skáld (Old Norse: [ˈskald], later [ˈskɒːld]; Icelandic: [ˈskault], meaning "poet"), is generally a term used for poets who composed at the courts of Scandinavian leaders during the Viking Age, 793–1066 AD, and continuing into the Middle Ages (5th century – 15th century). Skaldic poetry forms one of two main groupings of Old Norse poetry, the other being the anonymous Eddic poetry.[1] [2]

The most prevalent metre of skaldic poetry is dróttkvætt. The subject is usually historical and encomiastic, detailing the deeds of the skald's patron. There is no evidence that the skalds employed musical instruments, but some speculate that they may have accompanied their verses with the harp or lyre.[3][4]

The corpus of skaldic poetry comprise 5797 verses by 447 skalds preserved in 718 manuscripts.[5] It is currently being edited by the Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages project.[6]

Etymology

The word skald is perhaps ultimately related to Proto-Germanic: *skalliz, lit. 'sound, voice, shout' (Old High German: skal, lit. 'sound'). Old High German has skalsang, 'song of praise, psalm', and skellan, 'ring, clang, resound'. The Old High German variant stem skeltan etymologically identical to the skald- stem (Proto-Germanic: *skeldan) means "to scold, blame, accuse, insult". The person doing the insulting is a skelto or skeltāri. The West Germanic counterpart of the skald is the scop. Like the scop, which is related to Modern English scoff, the name skald is continued in English scold, reflecting the central position of mocking taunts in Germanic poetry. [7]

History

Skaldic poetry can be traced to the earlier-9th century with Bragi Boddason and his Ragnarsdrápa, considered among the oldest surviving Norse poems. Brage is the earliest skald whose verse has survived. [8][9]

However, many skalds came after him, like Egill Skallagrímsson and Torbjørn Hornklove (Þorbjörn Hornklofi), who gained much fame in the 10th century for the poems composed for the kings they served of their own exploits. At the time, the Icelanders and Nordic people were still pagan, and their work reflected that by many references to gods like Thor and Odin and to seers and runes.[10] The poetry from then also can be noted for its portrayal of a "heroic age" for the Vikings and "praise poetry, designed to commemorate kings and other prominent people, often in the form of quite long poems."[10][11][12]

As time went on, skalds became the main source of Icelandic and Norse history and culture, as it was the skalds who learned and shared the largely oral history.[13] That led to a shift in the role of the skald, allowing them to gain more prominent positions. Every king and chieftain needed a skald to record their feats and ensure their legacy lived on, as well as becoming the main historians of their society. The written artefacts of that time come from skalds, as they were the first from the time and place to record on paper. Some skalds became clerical workers, recording laws and happenings of the government, some even being elected to the Thing and Althing, while others worked with churches to record the lives and miracles of Saints, along with passing on the ideals of Christianity. The last point is very important, as skalds were the main agents of culture when they began glorifying and passing on Christianity over the old pagan beliefs, the Viking culture shifted towards Christianity, as well.

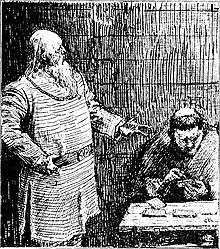

As time passed, the skald profession was threatened with extinction until Snorri Sturluson compiled the Prose Edda, as a manual to preserve an appreciative understanding of their art. Snorri, born in Iceland during the 12th century, played a very important part in the history of Skaldic poetry. In addition to being a great poet, he was leader of the Althing for part of his life, leading the government of Iceland. His Prose Edda preserved and passed on the traditions and methods of the Skalds, adding a much needed stimulus to the profession, and providing much of the information now known about skalds and how they worked. For example, the Prose Edda broke down and explained kennings used in skaldic poetry, allowing many of them to be understood today. Beyond writing the Prose Edda, Snorri wrote other important works, from retelling old Norse legends to tales of the exploits of kings, which gave him much fame and made his reputation live on beyond his death.[14] [15]

Skaldic poetry

Eddic verse was usually simple, in terms of content, style and metre, dealing largely with mythological or heroic content. Skaldic verse, conversely, was complex, and usually composed as a tribute or homage to a particular jarl or king. There is debate over the performance of skaldic poetry, but there is a general scholarly consensus that it was spoken rather than sung.[16]

Unlike many other literary forms of the time, much skaldic poetry is attributable to an author (called a skald), and those attributions may be relied on with a reasonable degree of confidence. Many skalds were men of influence and power and so were biographically noted. The metre is ornate, usually dróttkvætt or a variation thereof. The syntax is complex, with sentences commonly interwoven, with kennings and heiti being used frequently and gratuitously.

Skaldic poetry was written in variants and dialects of Old Norse. Technically, the verse was usually a form of alliterative verse and almost always used the dróttkvætt stanza (also known as the Court or Lordly Metre). Dróttkvætt is effectively an eight-line form, and each pair of lines is an original single long line which is conventionally written as two lines.

Forms

These are forms of skaldic poetry:

- Drápa, a long series of stanzas (usually dróttkvætt), with a refrain (stef) at intervals.

- Flokkr, vísur or dræplingr, a shorter series of such stanzas without refrain.

- Lausavísa, a single stanza of dróttkvætt, said to have been improvised impromptu for the occasion that it marks.

Skalds also composed insult (níðvísur) and very occasionally, erotic verse (mansöngr).

Kennings

The verses of the skalds contain a great profusion of kennings, the fixed metaphors found in most Northern European poetry of the time. Kennings are devices ready to supply a standard image to form an alliterating half-line to fit the requirements of dróttkvætt, but the substantially greater technical demands of skaldic verse required the devices to be multiplied and compounded to meet its demands for skill and wordplay. The images can therefore become somewhat hermetic, at least to those who fail to grasp the allusions that are at the root of many of them.[17]

Skaldic poems

Most skaldic poetry are poems composed to individual kings by their court poets. They typically have historical content, relating battles and other deeds from the king's career.

- Glymdrápa ‒ the deeds of Harald Fairhair.

- Vellekla ‒ the deeds of Haakon Sigurdsson.

- Bandadrápa ‒ the deeds of Eiríkr Hákonarson by Eyjólfr dáðaskáld

- Knútsdrápa ‒ the deeds of Cnut the Great.

A few surviving skaldic poems have mythological content.

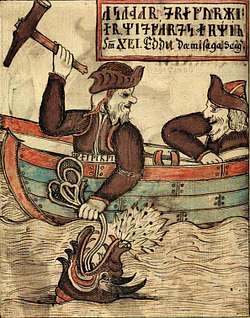

- Þórsdrápa ‒ a drápa to the god Thor telling the tale of one of his giant-bashing expeditions.

- Haustlöng ‒ relates two tales from the mythology as painted on a shield given to the poet.

- Ragnarsdrápa ‒ relates four tales from the mythology as painted on a shield given to the poet.

- Húsdrápa ‒ describes mythological scenes as carved on kitchen panels.

- Ynglingatal ‒ describes the origin of the Norwegian kings and the history of the Ynglings. It is preserved in the Heimskringla.

To that could be added two poems relating the death of a king and his reception in Valhalla.

- Hákonarmál ‒ the death of king Haakon the Good and his reception in Valhalla.

- Eiríksmál ‒ the death of king Eiríkr and his reception in Valhalla.

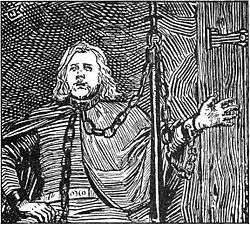

Some other were composed as circumstance pieces, such as those by Egill Skallagrímsson

- Sonatorrek ‒ a lament on the death of Egill's sons.

- Höfuðlausn ‒ a praise for Eric Bloodaxe, that saved its author's head.

- Arinbjarnarkviða ‒ in praise of the poet's friend Arinbjörn.

Notable skalds

More than 300 skalds are known from the period between 800 and 1200 AD. Many are listed in the Skáldatal, not all of whom are known from extant material. Notable names include:

- Bragi Boddason "the Old" (early-9th century), author of Ragnarsdrápa

- Þorbjörn Hornklofi (9th century) court poet of King Harald Fairhair

- Þjóðólfr of Hvinir (fl. c. 900), author of Haustlöng and Ynglingatal

- Eyvindr skáldaspillir (10th century), or Eyvindr the Plagiarist, the author of Hákonarmál and Háleygjatal

- Egill Skallagrímsson (10th century), author of Sonatorrek, Höfuðlausn and Arinbjarnarkviða

- Kormákr Ögmundarson (mid-10th century), the main character of Kormáks saga

- Eilífr Goðrúnarson (late-10th century), author of Þórsdrápa

- Þórvaldr Hjaltason (later-10th century), a skald of king Eric the Victorious

- Hallfreðr vandræðaskáld (late-10th century) court poet of Olaf Tryggvason

- Einarr Helgason "Skálaglamm" (late-10th century), "of the gleaming coins" ‒ author of Vellekla

- Úlfr Uggason (late-10th century), author of the Húsdrápa

- Tindr Hallkelsson (fl. c. 1000), one of Haakon Sigurdsson's court poets

- Gunnlaugr Ormstunga (10/11th century), nicknamed Ormstunga "Wormtongue" on account of his propensity for satire and invective

- Sigvatr Þórðarson (earlier-11th century), court poet to King Olaf II of Norway

- Þórarinn loftunga (earlier-11th century) court poet to Sveinn Knútsson

- Óttarr svarti (earlier-11th century), a skald at the court of king Olof Skötkonung and Olaf the Stout

- Arnórr jarlaskáld (mid-11th century), Jarlaskald "the Earls' Skald"

- Einarr Skúlason (12th century), author of Geisli

- Þórir Jökull Steinfinnsson (13th century) Icelandic poet

See also

- Old Norse poetry

- Alliterative verse

- Scop

- Bard

- Nīþ Puts the role of the skald into context as one who "shouted in their faces what they were in most derogatory terms".

References

- "skald". Store norske leksikon. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- Børge Nordbø. "skaldediktning". Store norske leksikon. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- Knut Helle (4 September 2003). The Cambridge History of Scandinavia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 551–. ISBN 978-0-521-47299-9. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- "Dróttkvætt". Skaldic Project Academic Body. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- Wills, Tarrin (2018-08-17). "Skaldic Project: Statistics". Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages. Archived from the original on 5 December 2019.

- Wills, Tarrin (2017-07-27). "Skaldic Project - Cross-Platform Interface". Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019.

- "scold". etymonline.com. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- "Brage Boddason Den Gamle". Norsk biografisk leksikon. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- "Ragnarsdrápa". heimskringla.no. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- "Egil Skallagrimsson and the Viking Ideal". fathom.lib.uchicago.edu.

- Christina von Nolcken. "Egil Skallagrimsson and the Viking Ideal". University of Chicago. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- "Torbjørn Hornklove". Norsk biografisk leksikon. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- The Skalds: A Selection of Their Poems, with Introduction and Notes by Lee M. Hollander Review by H. M. Smyser, “Speculum," Vol. 21, No. 2 (Apr. 1946), Medieval Academy of America

- "Snorri Sturluson - Icelandic writer". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Børge Nordbø. "Snorre Sturlason". Norsk biografisk leksikon. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- Gade, Kari Ellen (1995). The Structure of Old Norse Dróttkvætt Poetry. Cornell University Press. p. 25. ISBN 0801430232.

- "kenning". Store norske leksikon. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

Sources

- K. E. Gade (ed.) Poetry from the Kings' Sagas 2 from c. 1035 to c. 1300 (Brepols, 2009) ISBN 978-2-503-51897-8

- Margaret Clunies Ross (2007) Eddic, Skaldic, and Beyond: Poetic Variety in Medieval Iceland and Norway (Fordham University Press, 2014) ISBN 9780823257836

External links

- Dróttkvæði, skjaldkvæði og rímur from heimskringla.no.

- Finnur Jónsson, ed. Den norsk-islandske skjaldedigtning, from heimskringla.no.

- Finnur Jónsson, ed. Den norsk-islandske skjaldedigtning. 4 vols. Copenhagen: Villadsen og Christensen, 1912–15. Photographic reprint Copenhagen: Rosenkilde og Bagger, 1967. Still the definitive edition.

- Skaldic Project homepage: Skaldic poetry currently under edition (Clunies Ross et al.).

- Index of Old Norse/Icelandic Skaldic Poetry at the Jörmungrund database

- Sveinbjörn Egilsson and Finnur Jónsson, eds. Lexicon poeticum antiquæ linguæ septentriolanis: ordbog over det norsk-islandske skjaldesprog. 2nd ed. Copenhagen: Det kongelige nordiske oldskriftselskab, 1913–16 Also in partial form at the Jörmungrund database

- Corpus poeticum boreale. V. II. Court Poetry by G. Vigfússon and F. Y. Powell, 1883 at the Internet Archive: Skaldic poems with literal English translations