Treasure map

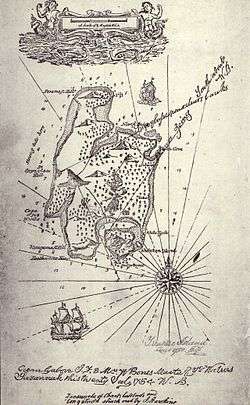

A treasure map is a map that marks the location of buried treasure, a lost mine, a valuable secret or a hidden locale. More common in fiction than in reality, "pirate treasure maps" are often depicted in works of fiction as hand drawn and containing arcane clues for the characters to follow. Regardless of the term's literary use, anything that meets the broad definition of a "map" that describes the location of a "treasure" could appropriately be called a "treasure map."

Treasure maps in history

Copper scroll

One of the earliest known instances of a document listing buried treasure is the copper scroll, which was recovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls near Qumran in 1952. Believed to have been written between 50 and 100 AD, the scroll contains a list of 63 locations with detailed directions pointing to hidden treasures of gold and silver. The following is an English translation of the opening lines of the Copper Scroll:[1]

1:1 In the ruin which is in the valley of Acor, under

1:2 the steps leading to the East,

1:3 forty long cubits: a chest of silver and its vessels1:4 with a weight of seventeen talents.

Thus far, no item mentioned in the scroll has been found. Scholars remain divided on whether the copper scroll represents real burials, and, if so, the total measurements and the owners.[2]

Pirates

Although buried pirate treasure is a favorite literary theme, there are very few documented cases of pirates actually burying treasure, and no documented cases of a historical pirate treasure map.[3] One documented case of buried treasure involved Francis Drake who buried Spanish gold and silver after raiding the train at Nombre de Dios—after Drake went to find his ships, he returned six hours later and retrieved the loot and sailed for England. Drake did not create a map.[3] Another case in 1720 involved British Captain Stratton of the Prince Eugene who, after supposedly trading rum with pirates in the Caribbean, buried his gold near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. One of his crew, Morgan Miles, turned him in to the authorities, and it is assumed the loot was recovered. In any case, Captain Stratton was not a pirate, and made no map.[3] Also see Olivier Levasseur.

The pirate most responsible for the legends of buried pirate treasure was Captain Kidd. The story was that Kidd buried treasure from the plundered ship the Quedah Merchant on Gardiner's Island, near Long Island, New York, before being captured and returned to England, where he was put through a very public trial and executed. Although much of Kidd's treasure was recovered from various people who had taken possession of it before Kidd's arrest (such as his wife and various others who were given it for safe keeping), there was so much public interest and fascination with the case at the time, speculation grew that a vast fortune remained and that Kidd had secretly buried it. Captain Kidd did bury a small cache of treasure on Gardiner's Island in a spot known as Cherry Tree Field; however, it was removed by Governor Bellomont and sent to England to be used as evidence against him.[4] Over the years many people have tried to find the supposed remnants of Kidd's treasure on Gardiner's Island and elsewhere, but none has ever been found.[3]

Over the years many people have claimed to have discovered maps and other clues that led to pirate treasure, or claim that historical maps are actually treasure maps. These claims are not supported by scholars.

El Dorado

In 1595, the English explorer Sir Walter Raleigh set out to find the legendary city of El Dorado.[5] Naturally, the city was never found but Raleigh wrote at length in The Discovery of Guiana about his venture to South America in which he claimed to have come within close proximity of "the great Golden Citie of Manoa (which the Spaniards call El Dorado)."[5] Despite the fact that his narrative was quite unrealistic—it described a tribe of headless people, for example—his reputation commanded such respect that other cartographers apparently used Raleigh's map as a model for their own. Cartographer Jodocus Hondius included El Dorado in his 1598 map of South America, as did Dutch publisher Theodore de Bry.[5] The city remained on maps of South America until as late as 1808[5] and spawned numerous unsuccessful hunts for the city.

Treasure maps in fiction

Treasure maps have taken on numerous permutations in literature and film, such as the stereotypical tattered chart with an "X" marking the spot, first made popular by Robert Louis Stevenson in Treasure Island (1883),[3] a cryptic puzzle (in Edgar Allan Poe's "The Gold-Bug" (1843)), or a tattoo leading to a dry-land paradise as seen in the film Waterworld (1995).

Literature

The treasure map may serve several purposes as a plot device in works of fiction:

- Motivation, causing the characters to begin a quest.

- Plot exposition, explaining in a concise way where the characters must go on their quest.

- To illustrate, at various points in the story, how far the quest has progressed.

- To provide challenges or obstacles for the characters, such as riddles or puzzles.

- To provide conflict where, for example, evildoers attempt to capture the map from the protagonists.

Robert Louis Stevenson popularized the treasure map idea in his novel Treasure Island, but he was not the first. Author James Fenimore Cooper's earlier 1849 novel The Sea Lions begins with the death of a sailor who left behind "two old, dirty and ragged charts", which lead to a seal-hunting paradise in the Antarctic and a location in the West Indies where pirates have buried treasure, a plot similar to Stevenson's tale.[6]

Film

The treasure map served as a major plot device in movies:

- In the 1984 film Romancing the Stone, a romance writer sets off to Colombia to ransom her kidnapped sister, and soon finds herself in the middle of a dangerous adventure.

- In the 1985 film The Goonies, an old treasure map leads to the secret stash of a legendary 17th-century pirate.

- In the 1994 comedy City Slickers II: The Legend of Curly's Gold, a treasure map is made by criminals.

- In the 1995 film Waterworld, an extremely vague and cryptic treasure map has been tattooed on the back of the child character Enola. This map leads the characters to dry land, which in the context of the film, is a treasure.

- In the 2000 animated comedy The Road to El Dorado, the principal characters win a map to the lost city of gold. They discover the city, are mistaken for gods, then help hide the city from the outside world.

- In the 2004 film National Treasure, the discovery of a hidden treasure map starts a quest for a treasure dating to the Colonial era.

- In the 2007 film National Treasure: Book of Secrets, treasure hunter Benjamin Gates uses an old map to find the lost city of Cibola.

See also

- Buried treasure

- Lost mines

- Montezuma's treasure

- Treasure

- Leprechauns

References

- García Martínez, Florentino and Eibert J. C. Tigchelaar, The Dead Sea Scrolls: Study Edition, Paperback ed. 2 vols., (Leiden and Grand Rapids: Brill and Eerdmans, 2000).

- Pixner, Bargil (Virgil) (1983-01-01). "UNRAVELLING THE COPPER SCROLL CODE A STUDY ON THE TOPOGRAPHY OF 3 Q 15". Revue de Qumrân. 11 (3 (43)): 323–365. JSTOR 24607018.

- Cordingly, David. (1995). Under the Black Flag: The Romance and the Reality of Life Among the Pirates. ISBN 0-679-42560-8.

- The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd, pg. 241, The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd, pg. 260

- Miles Harvey (2000). The Island of Lost Maps: A True Story of Cartographic Crime. ISBN 0-375-50151-7.

- Gates, W. B. (1950-01-01). "Cooper's the Sea Lions and Wilkes' Narrative". PMLA. 65 (6): 1069–1075. doi:10.2307/459720. JSTOR 459720.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Treasure maps. |