Ulfberht swords

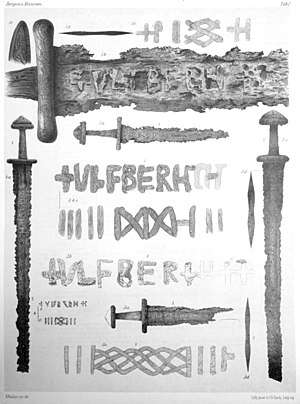

The Ulfberht swords are about 170 medieval swords found in Europe,[3] dated to the 9th to 11th centuries, with blades inlaid with the inscription +VLFBERH+T or +VLFBERHT+.[3][4] That word is a Frankish personal name that became the basis of a trademark of sorts, used by multiple bladesmiths for several centuries.

| Ulfberht swords | |

|---|---|

+VLFBEHT+ inscription on the blade of a 9th-century sword (Germanisches Nationalmuseum FG 2187) found in 1960 in the Old Rhine close to Friesenheimer Insel, Mannheim[1] | |

| Type | Sword |

| Production history | |

| Produced | 9th to 11th centuries |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | avg. 1.2 kg (2.7 lb) |

| Length | avg. 91 cm (36 in) |

| Width | 5 cm (2 in) |

| Blade type | Double-edged, straight bladed, slight taper |

| Hilt type | One-handed with pommel, variable guard |

| Head type | Acute distal taper, and point |

Description

The swords are at the transitional point between the Viking sword and the high medieval knightly sword. Most have blades of Oakeshott type X. They are also the starting point of the much more varied high medieval tradition of blade inscriptions. The reverse sides of the blades are inlaid with a geometric pattern, usually a braid pattern between vertical strokes. There are also numerous blades which have this type of geometric pattern but no Vlfberht inscription.[5]

Ulfberht swords were made during a period when European swords were still predominantly pattern welded ("false Damascus"),[6][7] but with larger blooms of steel gradually becoming available, so that higher quality swords made after AD 1000 are increasingly likely to have crucible steel blades. The group of Ulfberht swords includes a wide spectrum of steel and production methods. One example from a 10th-century grave in Nemilany, Moravia, has a pattern welded core with welded-on hardened cutting edges. Another example appears to have been made from high-quality hypoeutectoid steel possibly imported from Central Asia.[8]

Number and distribution

A total of 170 Ulfberht swords are known from Europe, most numerously in Northern Europe.[9][10] Most of them, 44 swords, are known from Norway and second most, 31 swords, from Finland.[3] However, the exact number of swords found is debatable because of the fragmentary condition of some examples, and because some inscriptions appear to be loose references to the Ulfberht type instead of actual specimens.[3][11]

The prevalence of Ulfberht swords in the archaeological record of Northern Europe does not imply that such swords were more widely used there than in Francia; the pagan practice of placing weapons in warrior graves greatly favours the archaeological record in such regions of Europe that were still pagan (and indeed most of the Ulfberht swords found in Norway are from warrior graves), while sword finds in continental Europe and England after the 7th century are mostly limited to stray finds; e.g., in riverbeds.[12]

Dating

The original Ulfberht sword type dates to the 9th or 10th century, but swords with the Ulfberht inscription continued to be made at least until the end of the Viking Age in the 11th century. A notable late example found in Eastern Germany, dated to the 11th or possibly early 12th century, represents the only specimen that combines the Vlfberht signature with a Christian "in nomine domini" inscription (+IINIOMINEDMN).[13] As a given name, Wulfbert (Old High German Wolfbert, Wolfbrecht, Wolfpert, Wolfperht, Vulpert) is recorded from the 8th to 10th centuries.[14]

Origin

The most likely place of origination of Ulberht swords is in the Rhineland region (i.e. in Austrasia, the core region of the Frankish realm, later part of the Franconian stem duchy). A Frankish origin of the original swords has long been assumed because of the form of the personal name Ulfberht; a sword found in Lower Saxony in 2012 used lead in its hilt which has reportedly been analysed as originating in the Taunus region, reinforcing the hypothesis of Frankish manufacture of the Ulfberht swords. [15] but were clearly sought-after, prestigious artefacts in Viking Age Scandinavia. Three specimens were found as far afield as Volga Bulgaria (at the time part of the Volga trade route).[2]

See also

- Viking Age arms and armour

- Ingelrii, a similar inscription type

- Blade inscription

References

- Treasures of German Art and History in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 2001, p. 23.

- Viacheslav Shpakovsky, David Nicolle, Gerry Embleton, Armies of the Volga Bulgars & Khanate of Kazan, 9th–16th centuries, Osprey Men-at-Arms 491 (2013), p. 23f.

- Moilanen, Mikko (2018). Viikinkimiekat Suomessa. Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura. pp. 169–175. ISBN 978-952-222-964-9.

- Wegeli (1904), p. 12, fig. 3.; Stralsberg (2008:6) classifies the "correctly" spelled inscriptions into five classes, 1. +VLFBERH+T (46 to 51 examples), 2. +VLFBERHT+ (18 to 23 examples), 3. VLFBERH+T (4 to 6 examples), 4. +VLFBERH┼T+ (1 or 2 examples), 5. +VLFBERH+T (10 examples), with a sixth class of "misspellings" (+VLEBERHIT, +VLFBEHT+, +VLFBERH+, +VLFBER├┼┼T, +VLFBERTH, 17 examples) and a seventh class "not definable" (31 or 32 examples). Stalsberg (2008) explains the numerous misspellings in the inscriptions by the "use of illiterate slaves in the smithy".

- Stalsberg (2008:2): "This indicates that geometrical and other marks were frequently welded into sword blades which have no signature, and it demonstrates that the technique of welding rods into the blade to make marks and signatures was known in many countries in Europe. This is a point to be kept in mind when discussing the question if Vlfberht blades or signatures may have been copied or falsified."

- Maryon, Herbert (February 1960). "Pattern-Welding and Damascening of Sword-Blades—Part 1: Pattern-Welding". Studies in Conservation. 5 (1): 25–37. doi:10.2307/1505063. JSTOR 1505063.

- Maryon, Herbert (May 1960). "Pattern-Welding and Damascening of Sword-Blades—Part 2: The Damascene Process". Studies in Conservation. 5 (2): 52–60. doi:10.2307/1504953. JSTOR 1504953.

- David Edge, Alan Williams: Some early medieval swords in the Wallace Collection and elsewhere, Gladius XXIII, 2003, 191-210 (p. 203).

- Stalsberg (2008:12): in terms of modern state borders: Norway: 44, Finland: 14, Germany: 13, Sweden: 12, Russia: 10 (excluding an additional c. 20 specimens found in Kaliningrad oblast, most of them at Linkuhnen cemetery), Estonia: 9, Latvia: 7, Poland: 7, Ukraine: 6, UK: 4; Denmark and Netherlands 3 each; Belgium, Croatia, Czech Republic, Iceland, Ireland, Lithuania: 2 each; Belarus, France, Italy, Spain, Switzerland: one each.

- Moilanen, Mikko, Marks of Fire, Value and Faith, Swords with Ferrous Inlays in Finland during the Late Iron Age (ca. 700 AD1200 AD), p. 126: Moilanen identifies 31 Ulfberht-swords in Finland, which is more than double the number stated by Stalsberg. Stalsberg's numbers are based on Leppäaho's findings from the 1960s.

- see Wegeli, p. 12, fig. 3.

- see e.g. E. A. Cameron, Sheaths and scabbards in England AD 400-1100 (2008), p. 34.

- Herrman, J. and Donat P. (eds.), Corpus archäologischer Quellen zur Frühgeschichte auf dem Gebiet der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik (7.-12. Jahrhundert), Akademie-Verlag, Berlin (1985), p. 376.

- Förstemann, Altdeutsches Namenbuch (1856) 1345.

- Hannover University (2015)

Works cited

- Anders Lorange, Den yngre jernalders sværd, Bergen (1889).

- Rudolf Wegeli, Inschriften auf mittelalterlichen Schwertklingen, Leipzig (1904).

- Anne Stalsberg, "Herstellung und Verbreitung der Vlfberht-Schwertklingen. Eine Neubewertung", Zeitschrift für Archäologie des Mittelalters 36, 2008, 89-118 (English translation).

- M. Müller-Wille: Ein neues ULFBERHT-Schwert aus Hamburg. Verbreitung, Formenkunde und Herkunft, Offa 27, 1970, 65-91