Battle of Cape Fear River (1718)

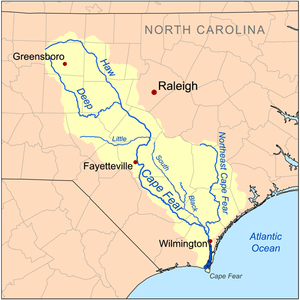

The Battle of Cape Fear River, or the Battle of the Sandbars, was fought in September 1718 between a British naval expedition from the Province of South Carolina against the pirate ships of Stede Bonnet. British forces defeated the pirates in the Cape Fear River estuary which led to Bonnet's death by hanging in Charleston.

Background

During the end of the Golden Age of Piracy, the Royal Navy was constantly in campaign against pirates in the Caribbean and off North America. Stede Bonnet was a very successful pirate, having captured several merchant ships and assembled his own squadron of pirate ships. In August 1718, Bonnet was sailing from the Delaware Bay to the Cape Fear River. He commanded his sloop-of-war flagship Royal James and two other armed sloops, Francis and Fortune. Royal James was a former flagship of Blackbeard which was armed with eight cannon. The other two sloops were similarly armed. All together, 46 pirates crewed them. Royal James was in need of careening and the hurricane season was soon to come so Bonnet chose the Cape Fear estuary as a reliable shelter against storms. For the next few weeks, Bonnet's crew repaired the Royal James with material salvaged from a captured shallop.

In late August, reports of Bonnet's sloops in the Cape Fear River reached Governor Robert Johnson of South Carolina. Johnson ordered Militia Colonel William Rhett to command an operation to destroy the pirate threat. He did not have regular Royal Navy Sailors under his command, but locally raised sailors from Charleston. At the colonel's disposal were two eight-gun sloops with a combined 130 men.

Battle

Colonel Rhett reached the Cape Fear River estuary on the night of September 26, 1718, and was sighted by Bonnet and his men. Believing the sloops to be that of merchants, the pirates boarded three canoes and headed for the unrecognized South Carolinian expedition. It was at this time that Rhett's flagship, Henry, ran aground on a sandbar. This allowed the canoes to approach close enough to discover the identity of the grounded vessel. Once they did they turned about and paddled back to their ships unharmed.

Instead of fleeing up the small river in darkness, Bonnet decided that he would fight his way back to the sea, so the next morning at daylight, the pirates prepared to pass the two British sloops, which were now free of the sandbar. They dispersed amongst Royal James, Fortune and Francis and loaded their arms. At daylight the following morning, Bonnet raised his flag and attacked. They sailed for a few minutes until they came within range of the enemy ships, then opened fire with cannon and muskets. The British sloops returned fire and split up, but Henry ran aground again along with the other ship. To avoid enemy fire, Stede Bonnet steered his vessels close to the western shore of the river, and they ran aground on sand.

At this point, only Henry and Royal James were within range of each other. For five to six hours, the two sides dueled, each unable to move. Henry was grounded in a position which left her crew with minimal cover from incoming fire. The opposite was true for Royal James, whose hull provided a bulwark against enemy fire. During the fighting, Bonnet stayed on deck with his pistol in hand and warned that he would shoot any man who showed cowardice. The pirates' morale was good though; they cheered each other on and dared the South Carolinians to board. After five hours of fighting the South Carolinians had suffered 30 casualties, with nine pirates also killed or injured.[1]

The British sloops were downstream, and when the water began to rise in the early afternoon, Rhett's sloops were freed, while Bonnet's remained stranded. The British repaired their rigging and raised their sails. Soon after, Henry was in a position to fire its starboard guns directly onto the deck of Bonnet's Royal James.[1] Bonnet ordered his gunner George Ross to light the powder magazine and scuttle Royal James, but he was persuaded not to by his surviving crewmen who had already surrendered. After another few moments of conflict, Royal James was boarded and its crew captured.[1]

Aftermath

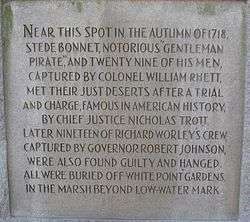

The South Carolinians suffered twelve killed and eighteen wounded, while the pirates sustained twelve casualties and all the survivors were captured.[1] Bonnet was taken to Charleston, arriving on October 3 to await trial on charges of piracy. Bonnet was separated from the majority of his crew and held for almost a month at the home of a Charleston provost marshal. With him was his boatswain, Ignatius Pell, and the sailing master, David Herriott, all of whom escaped with the help of two slaves and a Native American and possibly local merchant Richard Tookerman. Governor Robert Johnson immediately ordered a £700 bounty to be awarded to any man who could kill or capture the pirates. Herriott was shot and killed on Sullivan Island a few days later[2] and Bonnet, the gentleman pirate, was soon recaptured after a skirmish on Sullivan's Island and hanged on December 10, 1718.

References

- Konstam, Angus (2006). Blackbeard. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 194–195. ISBN 9780471758853.

- "Other Early Herriotts in America" (PDF). Herriottheritage.org. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

Further reading

- Cordingly, David. Under the Black Flag: The Romance and Reality of Life Among the Pirates New York: Random House, (1996) ISBN 0-679-42560-8.

- The Tryals of Major Stede Bonnet, and Other Pirates. London, Printed for Benj Cowse at the Rose and Crown in St Paul's Church-Yard, (1719)

- Woodard, Colin. The Republic of Pirates. New York: Harcourt, 2007. ISBN 978-0-15-603462-3.

- Lee, Robert E., Blackbeard the Pirate, North Carolina: John F. Blair (1974) ISBN 0-89587-032-0

External links

- Queen Anne's Revenge: Archaeological Site, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources

- Piracy worries in pirate pursuit Blackbeard, Baltimore Sun

- Out to Sea, Elite Magazine

- National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service

- Scientists Show Relics From Ship Fit For Pirate, Possibly Blackbeard, Chicago Tribune