Underwater hockey

Underwater hockey (UWH), also known as Octopush (mainly in the United Kingdom) is a globally played limited-contact sport in which two teams compete to manoeuvre a puck across the bottom of a swimming pool into the opposing team's goal by propelling it with a hockey stick (pusher). A key challenge of the game is that players are not able to use breathing devices such as scuba gear whilst playing, they must hold their breath. The game originated in England in 1954 when Alan Blake, a founder of the newly formed Southsea Sub-Aqua Club, invented the game he called Octopush as a means of keeping the club's members interested and active over the cold winter months when open-water diving lost its appeal.[1][2] Underwater hockey is now played worldwide, with the Confédération Mondiale des Activités Subaquatiques, abbreviated CMAS, as the world governing body.[3] The first Underwater Hockey World Championship was held in Canada in 1980 after a false start in 1979 brought about by international politics and apartheid.

Two players competing for the puck at GB Student Nationals, Bangor in 2009. | |

| Highest governing body | CMAS and World Aquachallenge Association (WAA) |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | UWH, Octopush |

| First played | 1954, Southsea, England |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Limited |

| Team members | up to 10 (6 in play) |

| Mixed gender | Yes |

| Type | Aquatic |

| Equipment | Diving mask, snorkel, fins, water polo cap, stick, protective glove, exterior mouth guard, puck |

| Venue | Swimming pool |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | no |

| Paralympic | no |

Play

Two teams of up to ten players compete, with six players in each team in play at any one time.[4] The remaining four players are continually substituted into play from a substitution area, which may be either on deck or in the water outside the playing area.

Before the start of play the puck is placed in the centre of the pool, and the players wait in the water whilst touching the wall above the goal they are defending. At the start-of-play signal (usually a buzzer or a gong) members of both teams are free to swim anywhere in the play area and try to score by manoeuvring the puck into the opponents' goal. Players hold their breath[5][6] as they dive to the bottom of the pool (a form of dynamic apnoea, as in free-diving). Play continues until either a goal is scored, when players return to their wall to start a new point, or a break in play is signalled by a referee (whether due to a foul, a time-out, or the end of the period of play).

Games consist of two halves of typically ten to fifteen minutes (depending on tournament rules; 20 minutes at World Championship tournaments) and a short half-time interval of usually three minutes. At half time the two teams switch ends.

A typical playing formation is 3-3 (three offensive players or forwards, and three defensive players or backs) of which 3-2-1 (three forwards, two mid-fielders and a back) is a variation. Other options include 2-3-1 (i.e., two forwards, three mid-fielders, and a back), 1-3-2, or 2-2-2. Formations are generally very fluid and are constantly evolving with different national teams being proponents of particular tweaks in formations, such as New Zealand with their 'box' (2-1-2-1) formation. As important to tournament teams' formation strategy is the substitution strategy; substitution errors might result in a foul (too many players in the play area) that can result in a player from the offending team being sent out, or maybe a tactical blunder (with too few defenders in on a play).

There are a number of penalties described in the official underwater hockey rules, ranging from the use of the stick against something (or someone) other than the puck, playing or stopping the puck with something other than the stick, and "blocking" (interposing one's self between a teammate who possesses the puck and an opponent; one is allowed to play the puck but not merely block opponents with one's body). If the penalty is minor, referees award an advantage puck: the team that committed the foul is pushed back 3 metres (9.8 ft) from the puck, while the other team gets free possession. For major penalties such as a dangerous pass (e.g. striking an opponent's head) or intentional or repeated fouls, the referees may eject players for a specified period of time or for the remainder of the game, or even - in the case of very serious or deliberate fouls - for the remainder of a tournament. A defender committing a serious foul sufficiently close to his own goal may be penalised by the award of a penalty shot or even a penalty goal awarded to the fouled player's team.

Often players who are most successful in this game are strong swimmers, have a great ability to hold and recover their breath, and are able to produce great speed underwater while demonstrating learned skills in puck control. It is also important that they are able to work well with their team members and take full advantage of their individual skills.

Injuries

Since this is an underwater sport, surface spectators may be unaware of just how physical underwater hockey is. Although it is a limited-contact sport, there is a significant risk of injury. Many injuries are typical sports injuries such as sprains, torn muscles and light scratches. More major injuries might include deeper cuts, broken fingers, impacts to the head causing concussion or dental trauma, and there is also a minor risk of life-threatening injury from being struck on the head with the possibility of a major concussion or blackout underwater. There is an obvious risk of drowning if knocked unconscious underwater, but the players are under observation by the referees during competition, and players in any case tend to be very aware of what their teammates are doing or not doing; in practice an unconscious or seriously injured player is likely to be noticed and assisted or rescued very promptly. Personal protective equipment is available to reduce injury risks, and the published rules make items such as gloves, mouth guards and ear guards mandatory. There is a risk of pulmonary capillary stress failure (Hemoptysis) in some players.[7]

Equipment

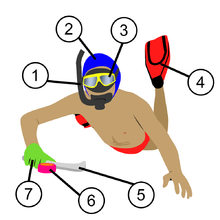

1. snorkel and mouth guard 2. hat with ear guards 3. mask 4. fins 5. stick 6. puck 7. glove

Players wear a diving mask, snorkel and fins, and carry in one (either) hand a short stick (or pusher) for playing the puck. A full list of equipment is given below:

Swimwear

There are usually no restrictions on swimwear, however baggy style trunks or shorts are not recommended as they reduce speed and increase drag in the water. Typical swimwear is swim briefs or jammers for male players and athletic style racerback two-piece swimsuits with drawstring bottoms or one-piece swimsuits for female players. Additionally, wetsuits are not allowed according to Rule 3.3.8 of the CMAS International Rules for Underwater Hockey, Eleventh Edition.

Mask

A diving mask is used for several reasons:

- Players can equalise their ears (using the Valsalva manoeuvre) as the nose is covered

- Unlike swim goggles, a mask sits outside the eye's orbit, reducing the effects of any impact

- Improved underwater vision

A low-volume mask with minimal protrusion from the face reduces the likelihood of the mask being knocked causing it to leak or flood and temporarily obstruct the player's vision. The published rules require masks to have two lenses to reduce the risk and extent of possible injury from puck impact; the danger of a single lens mask is that the aperture may be large enough to allow a puck to pass through it on impact, and hence into the player's eyes. A number of webbing strap designs are available to replace the original head strap with a non-elastic strap that can reduce the possibility of the player being unmasked.

Snorkel

A snorkel enables players to watch the progress of the game without having to lift their head from the water to breathe. This allows them to keep their position on the surface, ready to join play once they are able. In order to maximise the efficiency of breathing and reduce drag underwater snorkels are often short with a wide bore and may include a drain valve. The published rules mandate that they must not be rigid or have any sharp edges or points.

The snorkel may accommodate an external mouthguard which may be worn in conjunction with, or instead of, an internal mouthguard.

Fins

Fins allow the player to swim faster through the water. A wide variety of fins are used in the sport, but large plastic/rubber composite fins or smaller, stiffer fibreglass or carbon fibre fins are commonplace at competitions. As with any of the equipment, the published rules mandate fins without sharp edges or corners. All sharp edges must be covered up by a protective film to prevent injury. Players are also normally required to use closed-heel fins (without buckles) as a further injury prevention measure.[8]

Even well-fitting full-foot fins can occasionally be pulled off during play, either because of physical contact with something in the playing area or as a result of the power the wearer is transmitting through them into the water. When this occurs, stopping to refit a lost fin takes time and reduces a team to only 5 players. Fin grips, also known as fin retainers or fin keepers, are triple-strap devices enabling a closed-heel fin to be held more securely on a player's foot. They are worn around the arch, the heel and the instep to try and prevent the wearer's foot from slipping out of the foot-pocket of the fin.

Stick

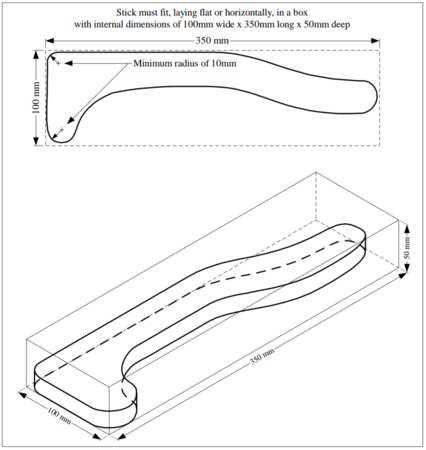

The stick (also referred to as a 'pusher') is relatively short and is coloured either white or black to indicate the player's team. The stick may only be held in one hand, which is usually determined by the player's handedness, although players may swap hands during play. The shape of the stick may affect playing style and is often a very personal choice. A wide variety of stick designs are allowed within the constraints of the rules of the game, the principal rules being that the stick (including the handle) must fit into a box of 100 mm × 50 mm × 350 mm (3.9 in × 2.0 in × 13.8 in) and that the stick must not be capable of surrounding either the puck or any part of the hand. A rule concerning the minimum radius of edges tries to address the risk of injury should body contact occur. Construction materials may be of wood or plastics and current rules now supersede those that previously required sticks to be homogeneous, although they almost always are anyway. Many UWH players manufacture their own sticks to their preferred shape and style, although there are increasingly more mass-produced designs to suit the majority (such as Bentfish, Britbat, CanAm, Dorsal, Stingray etc.).[8]

Puck

The puck is approximately the size of an ice hockey puck but is made of lead or lead-based material - (adult size weighs 1.3–1.5 kg (2.9–3.3 lb), junior 800–850 g (1.76–1.87 lb)) - and is encapsulated or surrounded by a plastic covering which is usually performance-matched to different pool bottoms (e.g. tiles, concrete etc.) to facilitate good grip on the stick face while preventing excessive friction on the pool bottom. The puck's weight brings it to rest on the pool bottom, though it can be lofted during passes.[8]

Caps

Safety gear includes ear protection, usually in the form of a water polo cap[9] and as a secondary indicator of the player's team (coloured black/dark or white/pale as appropriate). Water referees wear red caps.

Glove

A glove should be worn on the playing hand to protect against pool-bottom abrasion and, in some designs, for protection against puck impact on knuckles and other vulnerable areas, however no rigid protection is permitted. Players may choose to wear a protective glove on both hands, either as additional protection from the pool bottom or, for ambidextrous players, to switch the stick between hands mid-play. A glove used in competition must be a contrasting colour to the wearer's stick, but not orange which is reserved for referees' gloves - this is so water referees might be able to better distinguish between a pusher making a legal contact with the puck and a hand making an illegal contact with the puck. It is also usually preferred that a players glove is a different colour to the puck. As the puck is usually pink or orange it means players should avoid gloves coloured: Black, White, Red, Orange, Yellow and Pink. A referee at any match or tournament can ask a player to use different kit before they play, hence players should be careful when choosing the colour of their gloves. Blue is often used due to the limitations on glove colours, but others have also been used.[8]

Goal

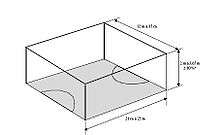

The goals (or 'gulleys') are 3 metres (9.8 ft) wide and are sited on the pool bottom at opposite ends of the playing area in the centre of the end lines. They consist of a shallow slope leading up to a trough into which the puck may be pushed or flicked.

Goals are commonly constructed from aluminium, galvanised steel or stainless steel. This makes them negatively buoyant and durable in the chlorinated water of swimming pools.

Referees

Officiating the game are two (or three) water referees (i.e. in the pool with full snorkelling gear, and wearing a distinctive red cap, orange gloves and golden yellow shirt) to observe and referee play at the pool bottom, and one or more poolside deck referees to track time (both playing times and penalty times for penalised players), maintain the score, and call fouls (such as excessive number of players in play, failure to start a point from the end of the playing area, or another foul capable of being committed at or noticed from the surface). The deck (chief) referee responds to hand signals given by the water referees to start and stop play, including after an interruption such as a foul or time-out, or indeed to stop play if they themself see a rule infringement.

The Official Rules, which are available for download in PDF form without charge, define (with illustrations) a valid goal, the fouls and signals, the dimensions of the playing area, sticks, and goals, team composition and substitution procedure, and additional rules and arrangements for multi-team tournaments and championships.[10][11]

Spectators

At a club or training level, underwater hockey is not particularly spectator friendly. Very few pools have underwater viewing ports, and since the action is all below the surface, an observer would usually have to enter the water to see the skill and complexities of the game. Spectators may either put on mask, fins and snorkel and enter the pool for a view of the playing area, or possibly take advantage of the work of underwater videographers who have recorded major tournaments.[12] Such tournaments often have live footage on large screens for the spectators which makes it a very exciting spectator sport. The 2006 (Sheffield, England) and 2010 (Durban, South Africa) Underwater Hockey World Championships were screened poolside and simultaneously webcast live to spectators around the world, while the 2008 European Championship in Istanbul, Turkey had excellent video coverage but no live streaming.[13]

Filming the games is challenging even for the experienced videographer, as the players' movements are fast and there are few places on the surface or beneath it which are free from their seemingly frenzied movements. Games are often played width-wise across a 50-metre pool to provide spaces in between simultaneous games for player substitutes, penalty boxes, coaches and camera crews. However, research and development of filming techniques is ongoing.

Organisers of major tournaments are usually the point of contact for acquiring footage of underwater hockey matches. Although no official worldwide repository exists for recorded games, there are many websites and instructional DVDs. A wide variety of related footage can be found on video sharing sites.[14]

History

Underwater hockey was started in the United Kingdom by Alan Blake in 1954. Blake was a founder-member of the newly formed Southsea Sub-Aqua Club (British Sub-Aqua Club No.9) and he and other divers including John Ventham, Jack Willis, and Frank Lilleker first played this game in Eastney Swimming Pool, Portsmouth, England.[15] Originally called "Octopush" (and still known locally by that name in the United Kingdom today), the original rules called for teams of eight players (hence "octo-"), a bat reminiscent of a tiny shuffleboard stick called a "pusher" (hence the "-push"), an uncoated lead puck called a "squid", and a goal known at first as a "cuttle" but soon thereafter a "gulley". Apart from 'pusher' and to a lesser extent 'Octopush' much of this original terminology is now consigned to history.

CMAS, the world governing body for underwater hockey, erroneously states on its website that the sport originated with the British Royal Navy in the 1950s.

The first rules were tested in a 1954 two-on-two game and Alan Blake made the following announcement in the November 1954 issue of the British Sub-Aqua Club's then-official magazine Neptune: "Our indoor training programme is getting under way, including wet activities other than in baths, and our new underwater game 'Octopush'. Of which more later when we have worked out the details".[16]

The first Octopush competition between clubs was a three-way tournament between teams from Southsea, Bournemouth and Brighton in early 1955. Southsea won then, and they are still highly ranked at national level today (they won again in 2009, 2012, 2014, 2017 and 2018).[17]

The sport spread to Durban, South Africa in the mid/late 1950s, thanks to the spearfishermen of the Durban Undersea Club (DUC),[18] when dirty summer seas prevented the young bloods from getting their weekly exercise and excitement. The first games were played in the pool of club member Max Doveton. However it soon became so popular that weekly contests were held in a municipal pool. The UK's Octopush used a small paddle to push the puck whilst the South Africans used a mini hockey stick. Whilst the 'long stick' version of underwater hockey did spread outside of South Africa, the UK's 'short stick' version ultimately prevailed and is how UWH is universally played now.

In the Americas, the game first came to Canada in 1962 via Norm Leibeck, an unconventional Australian scuba diving instructor and dive shop owner, who introduced the sport to a Vancouver dive club. Ten years later, the Underwater Hockey Association of British Columbia (UHABC) was formed and received support from the BC government.

Underwater hockey has been played in Australia since 1966, again because of Norm Leibeck, the same Australian who returned from Canada with his Canadian bride Marlene, and it now attracts players from a wide range of backgrounds there.[19] The first Australian Underwater Hockey Championships were held in Margaret River, Western Australia in 1975. A Women's division was added to the championships in 1981 and a Junior division commenced in 1990.[20]

In Asia, the game first came to the Philippines in the late 1970s through growing awareness of Octopush within the scuba diving community.

Footage from British Pathe of an early game at Aldershot Lido in 1967 ,[21] and from British Sub-Aqua Club archives,[22] is evidence of the evolution of the sport in terms of equipment and playing style. It can be seen that the game was much slower and the puck was not flicked at all, in contrast to the modern sport[14] where the substantial changes in equipment, team size, and other factors have helped make the game the international sport it is today, with 68 teams from 19 [23] countries competing at the 18th World Championship in 2013 at Eger in Hungary making this the pinnacle in terms of international competition to date.

When UWH started:

- 1954 UK

- 1960 Canada

- 1961 South Africa

- 1963 New Zealand

- 1967 France

- 1968 Australia

- 1968 France

- 1970 USA

- 1971 Holland

- 1979 Philippines

- 1979 Japan (suspended from 1989 to 2004, restarted 2004)

- 1980 Hong Kong (activities started in 1980 but stopped briefly, restarted 2015)

- 1982 Switzerland (no activities between 1986 and 2007)

- 1983 Argentina

- 1990 Colombia

- 1997 Germany

- 1997 Israel

- 1997 Italy

- 1997 Spain

- 2000 Moldova

- 2004 Singapore

- 2009 China

- 2010 Indonesia

- 2016 Saudi Arabia

- 2016 Brazil

- 2016 Malaysia

- 2017 UAE

- 2019 Korea

International competition

Underwater hockey enjoys popularity in the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, France, the Netherlands, New Zealand, South Africa and the United States, as well as to a lesser extent in other countries such as Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, China, Colombia, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Ireland, Israel, Japan, Namibia, the Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Rwanda, Serbia, Singapore, Slovenia, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey and Zimbabwe, and is gaining a foothold in numerous additional countries though maybe still not in Moldova.[24]

Historically, World Championships have been held every two years since 1980. At the Confédération Mondiale des Activités Subaquatiques (CMAS) 14th World Underwater Hockey Championship held in August 2006 in Sheffield, England, at the time a record 44 teams from 17 countries competed in six age and gender categories. Participating countries were Australia, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Hungary, France, Italy, Japan, Jersey C.I., the Netherlands, New Zealand, South Africa, Spain, Turkey, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and the United States. Subsequent world championships have been less well-attended including the WAA World Championship held in 2008 in Durban, South Africa, until the 18th CMAS World Championship[25] was held in Eger, Hungary in August 2013. This event once again saw all age and gender divisions, now including men and women in U19, U23, Masters and Elite categories compete. There were 68 teams competing across the eight age/gender divisions from 19 participating countries, making this World Championship the largest competition in the history of the sport to date. During the 18th World Championships a decision was made by the federations to split the competition into two events with Junior Grades (U19, U23) to be accommodated in a separate event[26] to be held every two years from 2015 with the competition[27] for the Elite and Masters grades in Stellenbosch, South Africa in 2016.

At Elite level New Zealand are the current Men's World Champions, and New Zealand are the current Women's World Champions. At Masters level France are the current Men's World Champions, and France are the current Women's World Champions. At U24 level Turkey are the current Men's World Champions, and New Zealand are the current Women's World Champions. At U19 level New Zealand are the current Men's World Champions, and New Zealand are the current Women's World Champions.

The next World Championship for Elite and Masters grades is due to be held in Brisbane, Australia in July 2021 (postponed by one year due to COVID-19). The Last World Championship for the Age Groups was held in Sheffield, England in August 2019. The next will be held in 2022 (postponed by one year due to COVID-19)

Underwater Hockey was included as a sport for the first time in South East Asia Games in 2019[28]

Governing bodies

Political turmoil within the CMAS Underwater Hockey Commission,[29] the underwater hockey world governing body, came to a head soon after the 2006 World Championship, resulting in the CMAS Underwater Hockey Commission members resigning en masse and soon thereafter forming an alternative 'world governing body' solely for the sport of UWH, known as the World Aquachallenge Association (WAA), and which was officially ratified at the 1st WAA World Championship in April–May 2008.[30] Consequently, from this point the UWH community had two world governing bodies, CMAS and WAA.

CMAS has continued to organise international world competitions on a bi-annual basis. CMAS tried unsuccessfully to hold another World Underwater Games event in 2009 after a successful event in 2007. These were intended to be multi-disciplinary events thereby grouping UWH with other CMAS-represented sports including fin swimming and underwater rugby. The 1st World Games were held in Bari, Italy in 2007 while the 2nd was scheduled for Tunisia in 2009 but was cancelled and rescheduled as an UWH-only event held in Kranj, Slovenia during August 2009. It was billed as a World Championship but only one non-European country competed (South Africa); France won the Open division while Great Britain took the Women's title. In the years in between World Games CMAS holds Zone Championships (e.g. the 15th European Championship in Eger, Hungary during 2017).

WAA attempted to continue with the original World Championship series on a biennial basis during years ending with an even number. The 1st WAA Championships (renumbered; it would have been the CMAS 15th) was held in 2008 in Durban, South Africa. The 2nd competition was scheduled for Medellin, Colombia in August 2010 but it proceeded as an International Event without WAA sanctioning and became the precursor for the development of the independent America's Cup International Tournament.[31]

The European (CMAS) and the rest of the World (WAA) events following the split were held over exactly the same period in 2008 a continent apart. This dichotomy of championships coupled with the real possibility of future sanctions by CMAS on their member countries' organisations and athletes led to many countries being forced to choose which competition to send their team to. As a result, neither competition in 2008 was as well attended as had been the case in previous years, nor as competitive. Subsequently, no WAA sanctioned events have taken place since 2008. However, in Europe at least, well-organised international tournaments without CMAS or WAA influence (such as at Breda in the Netherlands, Barcelona in Spain, or České Budějovice in the Czech Republic) continue to be regularly attended by a range of club teams from across the continent.[32][33][34]

In 2009, a new CMAS Underwater Hockey Commission was appointed for a 4-year period to guide the sport on a technical level and gradually it has reconsolidated the sport and produced a development plan to cope with future growth. The commission continues to work to develop relationships with CMAS Board of Directors and obtain support for its development plan.

As part of this plan the Commission developed an Age Group-based International Championship incorporating Under 19, Under 23 and Masters (Men >35, Women >32) Grades. This Championship was held in July 2011 in Dordrecht, Netherlands. The event was to be sanctioned by CMAS but the Dutch organising team withdrew their hosting bid and proceeded to host the event successfully with 36 teams participating. As the event was non-compliant with the CMAS Competition procedures, Scotland was able to compete as a separate country rather than within a combined entity as Great Britain.[35]

As the surviving governing body, as of August 2013 CMAS has the following countries and territories affiliated with its Underwater Hockey Commission: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hong Kong, Hungary, Indonesia, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, New Zealand, Portugal, Serbia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Turkey, United States of America.[36]

See also

- Underwater Hockey World Championships – International event for the sport of Underwater Hockey

References

- "The History of Underwater Hockey". Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- "Alan Blake - How Octopush was created". Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- "CMAS Underwater Hockey Commission". Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- CMAS (September 2005). "International Rules for Underwater Hockey: Rules of Play". Confédération Mondiale des Activités Subaquatiques. Retrieved 2012-08-30.

- Davis FM; Graves MP; Guy HJ; Prisk GK; Tanner TE (November 1987). "Carbon dioxide response and breath-hold times in underwater hockey players". Undersea Biomed Res. 14 (6): 527–34. PMID 3120387. Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- Lemaître F, Polin D, Joulia F, Boutry A, Le Pessot D, Chollet D, Tourny-Chollet C (December 2007). "Physiological responses to repeated apneas in underwater hockey players and controls". Undersea Hyperb Med. 34 (6): 407–14. ISSN 1066-2936. PMID 18251437. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- "Lung physiology at play: Hemoptysis due to underwater hockey". Respiratory Medicine Case Reports.

- "INTERNATIONAL RULES FOR UNDER WATER HOCKEY" (PDF). www.gbuwh.co.uk. 2011. Retrieved 2019-07-11.

- Landsberg PG (December 1976). "South African Underwater Diving Accidents, 1969-1976" (PDF). SA Medical Journal: 2156. Retrieved 2013-03-29.

- Hockey Rules Volume 1 and 2, & , retrieved 16/04/2018.

- Rules Volumes 1 and 2, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2012-08-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) & "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28. Retrieved 2012-08-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), retrieved 30/08/2012.

- "New sport is not out of its depth". BBC News. 17 December 2005. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- "2006 CMAS Underwater Hockey WC". 247.tv. 2006. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- "Various UWH clips". YouTube. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- Blake, A. "Octopush: An original name invented on the same night as Octopush an original sport was invented". Retrieved 2008-07-22.

- "Round the Branches: It's Back to the Baths", Neptune Vol. 1 No. 3, November 1954. p. 10.

- "The British Octopush Association - History". Gbuwh.co.uk. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- CMAS. "Underwater Hockey in South Africa". Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- Quilford, R. (17 December 2007). "Breath-taking fun for anyone". The Age. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- "The History of Underwater Hockey in Australia". BBC News. 11 September 2011. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

- "Underwater Hockey video newsreel film". British Pathe. December 1967. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- "BSAC Archives Footage". facebook. BSAC.

- "2006 CMAS Underwater Hockey World Championships". August 2006. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- "Moldovans snorkel to new life". BBC News. 11 March 2003. Retrieved 2011-06-28.

- "Underwater Hockey World Championship 2013 Eger - Hungary. Information Pack is out". CMAS. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- 3rd Age Group World Championship

- 19th World Championship

- Kng, Zheng Guan (28 November 2019). "Chance to give Octopush a big push". New Strait Times. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "About Underwater Hockey". CMAS. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- "2008 Meeting Minutes (on WAA News Page)" (PDF). WAA. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- "Open World Cup UWH 2010 USA results". USA Underwater Hockey. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- "Teams for the Argonauta 2013 UWH Tournament". Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- "XIV International UWH Tournament Barcelona 2013 Results". Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- "6th International UWH Bud Pig Cup". Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- "Netherlands Open Youth & Masters Underwater Hockey Tournament". www.underwaterhockey-archive.com/. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- "CMAS, Sport, UWH Commission, Member Federations". Retrieved 29 August 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Underwater hockey. |