Buzkashi

Buzkashi (بزکشی, literally "goat pulling" in Persian) is a Central Asian sport in which horse-mounted players attempt to place a goat or calf carcass in a goal. Similar games are known as kokpar,[1] kupkari,[2] and ulak tartysh[3] in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, and as kökbörü and gökbörü in Turkey, where it is played mainly by communities originally from Central Asia.[4]

History

Buzkashi began among the nomadic Turkic peoples who came from farther north and east spreading westward from China and Mongolia between the 10th and 15th centuries in a centuries-long series of migrations that ended only in the 1930s. From Scythian times until recent decades, buzkashi has remained a legacy of that bygone era.[5][6]

During the rule of the Taliban regime, buzkashi was banned in Afghanistan, as the Taliban considered the game immoral. After the Taliban regime was ousted, the game resumed being played.[7][8]

Distribution

Today games similar to buzkashi are played by several Central Asian ethnic groups such as the Kyrgyz, Turkmens, Kazakhs, Uzbeks, Uyghurs, Hazaras, Tajiks, Pashtuns, and Baloch people. In the West, the game is also played by Afghan Turks (ethnic Kyrgyz) who migrated to Ulupamir village in the Van district of Turkey from the Pamir region. In western China, there is not only horse-back buzkashi, but also yak buzkashi among Tajiks of Xinjiang.[9]

Afghanistan

Buzkashi is the national sport and a "passion" in Afghanistan where it is often played on Fridays and matches draw thousands of fans. Whitney Azoy notes in his book Buzkashi: Game and Power in Afghanistan that "leaders are men who can seize control by means foul and fair and then fight off their rivals. The Buzkashi rider does the same".[10] Traditionally, games could last for several days, but in its more regulated tournament version, it has a limited match time.

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan's first National Kokpar Association was registered in 2000. The association has been holding annual kokpar championships among adults since 2001 and youth kokpar championships since 2005. All 14 regions of Kazakhstan have professional kokpar teams. The regions with the biggest number of professional kokpar teams are Southern Kazakhstan with 32 professional teams, Jambyl region with 27 teams and Akmola region with 18 teams. Kazakhstan's national kokpar team currently holds a title of Eurasian kokpar champions.[11]

Kyrgyzstan

A photograph documents kokboru players in Kyrgyzstan around 1870;[12] however, Kyrgyzstan's kokboru rules were first officially defined and regulated in 1949. Starting from 1958 kokboru began being held in hippodromes. The size of a kokboru field depends on the number of participants.[13]

Tajikistan

The buzkashi season in Tajikistan generally runs from November through April. High temperatures often prevent matches from taking place outside of this period, though isolated games might be found in some cooler mountain areas.

In Tajikistan and among the Tajik people of Tashkorgan in China's Xinjiang region, buzkashi games are particularly popular in relation to weddings as the games are sponsored by the father of the bride as part of the festivities.[14]

United States

Buzkashi was brought to the U.S. by a descendant from the Afghan Royal Family, the family of King Amanullah and King Zahir Shah. A mounted version of the game has also been played in the United States in the 1940s. Young men in Cleveland, Ohio played a game they called Kav Kaz. The men – five to a team – played on horseback with a sheepskin-covered ball. The Greater Cleveland area had six or seven teams. The game was divided into three "chukkers", somewhat like polo. The field was about the size of a football field and had goals at each end: large wooden frameworks standing on tripods, with holes about two feet square. The players carried the ball in their hands, holding it by the long-fleeced sheepskin. A team had to pass the ball three times before throwing it into the goal. If the ball fell to the ground, the player had to reach down from his horse to pick it up. One player recalls, "Others would try to unseat the rider as he leaned over. They would grab you by the shoulder to shove you off. There weren't many rules."[15]

Mounted team-based potato races, a popular pastime in early 20th-century America, bore some resemblance to buzkashi, although on a much smaller and tamer scale.[16]

Rules and variations

Competition is typically fierce. Prior to the establishment of official rules by the Afghan Olympic Federation, the sport was mainly conducted based upon rules such as not whipping a fellow rider intentionally or deliberately knocking him off his horse. Riders usually wear heavy clothing and head protection to protect themselves against other players' whips and boots. For example, riders in the former Soviet Union often wear salvaged Soviet tank helmets for protection. The boots usually have high heels that lock into the saddle of the horse to help the rider lean on the side of the horse while trying to pick up the goat. Games can last for several days, and the winning team receives a prize, not necessarily money, as a reward for their win. Top players, such as Aziz Ahmad, are often sponsored by wealthy Afghans.[17]

A buzkashi player is called a Chapandaz; it is mainly believed in Afghanistan that a skillful Chapandaz is usually in his forties. This is based on the fact that the nature of the game requires its player to undergo severe physical practice and observation. Similarly horses used in buzkashi also undergo severe training and due attention. A player does not necessarily own the horse. Horses are usually owned by landlords and highly rich people wealthy enough to look after and provide for training facilities for such horses. However a master Chapandaz can choose to select any horse and the owner of the horse usually wants his horse to be ridden by a master Chapandaz as a winning horse also brings pride to the owner.

The game consists of two main forms: Tudabarai and Qarajai. Tudabarai is considered to be the simpler form of the game. In this version, the goal is simply to grab the goat and move in any direction until clear of the other players. In Qarajai, players must carry the carcass around a flag or marker at one end of the field, then throw it into a scoring circle (the "Circle of Justice") at the other end. The riders will carry a whip to fend off opposing horses and riders. When not in use - e.g. because the rider needs both hands to steer the horse and secure the carcass - the whip is typically carried in the teeth.

The calf in a buzkashi game is normally beheaded and disemboweled and has 2 limbs cut off. It is then soaked in cold water for 24 hours before play to toughen it. Occasionally sand is packed into the carcass to give it extra weight. Though a goat is used when no calf is available, a calf is less likely to disintegrate during the game. While players may not strap the calf to their bodies or saddles, it is acceptable - and common practice - to wedge the calf under one leg in order to free up the hands.

Afghanistan

These rules are strictly observed only for contests in Kabul.[18]

- The ground has a square layout with each side long.

- Each team consists of 10 riders.

- Only five riders from each team can play in a half.

- The total duration of each half is 45 minutes.

- There is only one 15 minute break between the two halves.

- The game is supervised by a referee.

Kyrgyzstan

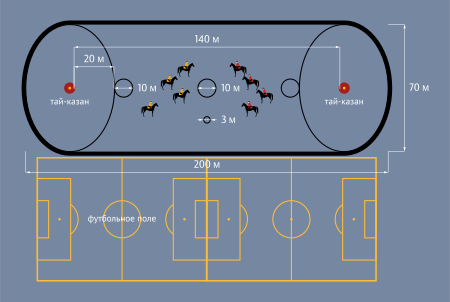

Rules of kokboru have undergone several changes throughout history. Modernized rules of kokboru are:

- There are two teams with 12 participants each.

- Only 4 players a team are allowed to play on the field at any given time.

- Teams are allowed to substitute players or their horses.

- The game is played on a field 200 meters long and 70 meters wide.

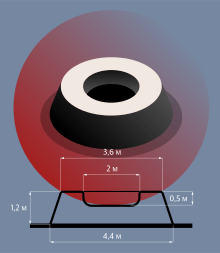

- Two kazans – big goals with a 4.4 meters in diameter and 1.2 meters high are placed on opposite sides of a field.

- The total duration of three periods is 60 minutes.

- There is a 10 minute break between each period.

- A goal is scored each time a ulak (goat carcass) is placed in an opponent's kazan.

- A kokboru is brought to centre of the field after scoring a goal.

It is also prohibited to ride towards the spectators and/or receive spectators' assistance or to start a kokboru game without giving an oath to play justly.

Tajikistan

In Tajikistan, buzkashi is played in a variety of ways. The most common iteration is a free-form game, often played in a mountain valley or other natural arena, in which each player competes individually to seize the buz and carry it to a goal. Forming unofficial teams or alliances does occur, but is discouraged in favor of individual play. Often, dozens of riders will compete against one another simultaneously, making the scrum to retrieve a fallen buz a chaotic affair. Tajik buzkashi games typically consist of many short matches, with a prize being awarded to each player who successfully scores a point.

In popular culture

In books and film adaptations

Buzkashi is portrayed in several books, both fiction and non-fiction. It is shown in Steve Berry's book The Venetian Betrayal, and it is briefly mentioned in the Khaled Hosseini book The Kite Runner. Buzkashi was the subject of a book called Horsemen of Afghanistan by French photojournalists Roland and Sabrina Michaud. Gino Strada wrote a book named after the sport (with the spelling Buskashì) in which he tells about his life as surgeon in Kabul in the days after the 9-11 strikes. P.J. O'Rourke also mentions the game in discussions about Afghanistan and Pakistan in the Foreign Policy section of Parliament of Whores, and Rory Stewart devotes a few sentences to it in "The Places in Between".

Two books have been written about buzkashi which were later turned into films. The game is the subject of a novel by French novelist Joseph Kessel titled Les Cavaliers (aka Horsemen), which then became the basis of the film The Horsemen (1971). The film was directed by John Frankenheimer with Omar Sharif in the lead role, and U.S. actor and accomplished horseman Jack Palance as his father, a legendary retired chapandaz. This film shows Afghanistan and its people the way they were before the wars that wracked the country, particularly their love for the sport of buzkashi.

The game is also a key element in the book Caravans by James Michener and the film of the same name (1978) starring Anthony Quinn. A scene from the film featuring the king of Afghanistan watching a game included the real-life king at the time, Mohammed Zahir Shah. The whole sequence of the game being witnessed by the king was filmed on the Kabul Golf Course, where the national championships were played at the time the film was made.

In Ken Follett's book, Lie Down with Lions (1986), the game is mentioned being played, but instead of a goat, they used a live Russian soldier.

In film

A number of films also reference the game. fr: La Passe du Diable (1956), by Jacques Dupont and Pierre Schoendoerfer. The Horsemen (1971) starring Jack Palance and Omar Sharif as father and son is centered on the game. Both La Passe du Diable and The Horseman are based on a novel by Joseph Kessel. In Rambo III (1988), directed by Peter MacDonald, John Rambo (played by Sylvester Stallone) was shown in a sequence playing and scoring in a buzkashi with his mujahideen friends when suddenly they were attacked by the Soviets. The Tom Selleck film High Road to China (1983) features a spirited game of buzkashi. Buzkashi is described at length in Episode 2, "The Harvest of the Seasons", of the documentary The Ascent of Man by Jacob Bronowski. It is put in the context of the development, by the Mongols, of warfare using the horse and its effect on agricultural settlements. The film includes several scenes from a game in Afghanistan. The opening scenes of the Bollywood film Khuda Gawah (1992), which was filmed in Afghanistan and India, show actors Amitabh Bachchan and Sridevi engaged in the game. The game is mentioned briefly in John Huston's film The Man Who Would Be King (1975) based on a story by Rudyard Kipling, the movie Dodgeball: A True Underdog Story (2004) during advertisements for the fictional ESPN 8 (El Ocho) television channel and episode 15 of season 5 of NCIS: Los Angeles (2015).

The 2012 joint international-Afghan short film Buzkashi Boys depicts a fictional story centered on the game, and has won awards at several international film festivals.[19] On January 10, 2013, The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences nominated Buzkashi Boys for an Oscar in the category of Short Film (Live Action) for the 85th Academy Awards.[20]

Venerated Buzkashi (ulak tartysh in Kyrgyz) player, 82 year old veteran school teacher Khamid Boronov stars in 2016 feature documentary film Letters from the Pamirs by Janyl Jusupjan. Famed Buzkashi players of Jaylgan village Shamsidin and Kazyke appear in a sequence to show the elements of Buzkashi to kids from a town. A spirited Buzkashi match is one of the last episodes of the film made in Jerge-Tal Kyrgyz region in Tajikistan's north.

Buzkashi is mentioned in The Secret Life of Walter Mitty where it is translated as 'Goat Hockey' and is a clue to the location of 'Sean O'Connell'.

See also

- Pato, a similar horseback Argentine sport

- Horseball, another game played on horseback

- Yak racing

- Polo, a similar horseback game played with a ball

References

- "Dom Joly: Know your Kokpar from your Kyz-Kuu" Archived 2017-08-28 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent: Columnists

- "Traditions: Kupkari" Archived 2013-10-12 at the Wayback Machine, ZOOM Central Asia

- "Bishkek's Independence Day Celebrations: Ulak Tartysh, the Art of Dead Goat Grabbing - Caravanistan". caravanistan.com. 2 May 2014. Archived from the original on 2016-03-26. Retrieved 2016-04-08.

- "Kökbörü – Etnospor Kültür Festivali". etnosporfestivali.com. Archived from the original on 2017-05-13. Retrieved 2017-05-12.

- G. Whitney Azoy, Buzkashi: Game and Power in Afghanistan, Third Edition. Waveland Press 2011. pp.3-4.

- G. Whitney Azoy, Buzkashi: Game and Power in Afghanistan, 2nd ed. (2002), In: Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias "buzkashi" Archived 2014-09-06 at the Wayback Machine

- "Afghanistan: By Their Sports, Ye Shall Know Them". TIME.com. Archived from the original on 2010-11-14. Retrieved 2009-08-31.

- "Afghans revive 'buzkashi'". www.usatoday.com. Archived from the original on 2010-02-20. Retrieved 2017-08-25.

- 塔什库尔干:高天下的太阳部落. p. 162. ASIN B00AZKSHHS. ISBN 7-5613-2787-0.

- Tony Perry Afghans love to get their goat in rough national sport January 3, 2009 page A20 LA Times

- "Кокпар". zhigerastana.kz. Archived from the original on 2013-07-30. Retrieved 2013-03-19.

- "Everyday Kyrgyz Pastimes. Kok-Boru, a Traditional Sport Played on Horseback with the Carcass of a Goat". World Digital Library. Archived from the original on 2014-05-15. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- The nomad game

- Summers, Josh. "Buzkashi Explained: Mysterious Rules & Traditions". Far West China. Archived from the original on 2017-12-11. Retrieved 2017-12-11.

- Dean, Ruth and Melissa Thomson, Making the Good Earth Better: The Heritage of Kurtz Bros., Inc. pp. 17–18

- Hoy, Jim; Isern, Tom (1987). Plains Folk: A Commonplace of the Great Plains. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 126. ISBN 9780806120645. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

potato race.

- Abi-Habib, Maria; Fazly, Walid (13 April 2011). "In Afghanistan's National Pastime, It's Better to Be a Hero Than a Goat". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 2015-05-26. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- "Buzkashi: The National Game of Afghanis". Embassy of Afghanistan in Australia. Archived from the original on 2014-09-30. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- "Beyond the bombs: Afghanistan's toughest sport also source of hope – World News". Worldnews.nbcnews.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-31. Retrieved 2013-06-04.

- "Nominees for the 85th Academy Awards | Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences". Oscars.org. 2012-08-24. Archived from the original on 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2013-06-04.

Further reading

- G. Whitney Azoy (2003), Buzkashi: Game and Power in Afghanistan, 2nd ed. Waveland Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1577667209

- "Ancient Kyrgyz game may captivate Europe", The Times of Central Asia, 9 November 2006 (www.timesca.com)

- V. Kadyrov, Kyrgyzstan: Traditions of Nomads, Rarity Ltd., Bishkek, 2005 ISBN 9967-424-42-7

- Boast, Will (Summer 2017). "A Kingdom for a Horse: Kokpar and the Future of Kazakhstan | VQR Online". Virginia Quarterly Review. 93 (3). – Kokpar in present-day Kazakhstan

External links

- Traditional Oglak Tartis

- Photo-essay on Buzkashi in Tajikistan

- What is the biggest Kazakh sport?

- Afghanistan Buzkashi Pictures

- Afghanistan Online: Afghan National Sport (Buzkashi)

- Buzkashi – Afghanistan's Lovable National Sport

- Kok boru video on YouTube (in Turkish)

- Kok boru video (in Turkish)

- Buzkashi in Mazar-e Sharif in 2014