Bandy

Bandy is a team winter sport played on ice, in which skaters use sticks to direct a ball into the opposing team's goal.[2]

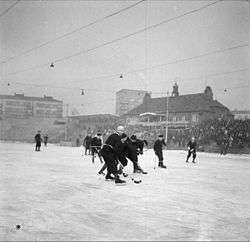

Swedish bandy players in January 2011 | |

| Highest governing body | Federation of International Bandy |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | Winter football[1] |

| First played | 1813 in Huntingdonshire, England |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Yes |

| Team members | 11 field players |

| Type | Team sport, winter sport |

| Equipment | Bandy ball, bandy stick, skates, protective gear |

| Venue | Ice field, bandy arena |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | Demonstration 1952 |

The sport is considered a form of hockey and has a common background with ice hockey and field hockey. Bandy has also been influenced by the rules of association football: both games are normally played in halves of 45 minutes, there are 11 players on each team, and the fields in both games are about the same size. Bandy is played, like ice hockey, on ice but players use bowed sticks and a small ball, as in field hockey.

A variant of bandy, rink bandy, is played to the same rules but on a field the size of an ice hockey rink, with ice hockey goal cages and with six players on each team, or five in USA Rink Bandy League. Traditional eleven-a-side bandy and rink bandy are recognized by the International Olympic Committee. More informal varieties also exist, like seven-a-side bandy with normally sized goal cages but without corner strokes. Those rules were applied at Davos Cup in 2016.

Rink bandy has in turn led to the creation of the sport rinkball. Bandy is also the predecessor of floorball, which was invented when people started playing with plastic bandy-shaped sticks and lightweight balls when running on the floors of indoor gym halls.

Based on the number of participating athletes, bandy is the world's second-most participated winter sport after ice hockey.[3][4][5] Bandy is also ranked as the number two winter sport in terms of tickets sold per day of competitions at the sport's world championship.[4]

However, compared with the seven Winter Olympic sports, bandy's popularity compared to that of other winter sports across the globe is considered by the International Olympic Committee to represent a "gap between popularity and participation and global audiences." This is held to constitute a roadblock to future Olympic inclusion.[6]

History

Background

The earliest origin of the sport is debated. Though many Russians see their old countrymen as the creators of the sport – reflected by the unofficial title for bandy, "Russian hockey" (русский хоккей) – Russia,[7] England and Holland each had sports or pastimes which can be seen as forerunners of the present sport.[8]

Early days

English bandy developed as a winter sport in the Fens of East Anglia. Large expanses of ice would form on the flooded meadows or shallow washes in cold winters, and skating has been a tradition. Members of the Bury Fen Bandy Club[9] published rules of the game in 1882, and introduced it into other countries. The first international match took place in 1891 between Bury Fen and the then Haarlemsche Hockey & Bandy Club from the Netherlands (a club which after a couple of club fusions now is named HC Bloemendaal). The same year, the National Bandy Association was started in England.[10]

The match later dubbed "the original bandy match", was actually held in 1875 at The Crystal Palace in London. However, at the time, the game was called "hockey on the ice",[10] probably as it was considered an ice variant of field hockey.

Modern development

The first national bandy league was started in Sweden in 1902.[10] Bandy was played at the Nordic Games in Stockholm and Kristiania (present day Oslo) in 1901, 1903, and 1905 and between Swedish, Finnish and Russian teams at similar games in Helsinki in 1907.[11] A European championship was held in 1913 with eight countries participating.[10]

In modern times, Russia has held a top position in the bandy area, both as a founding nation of the International Federation in 1955 and fielding the most successful team in the World Championships (when counting the previous Soviet Union team and Russia together).

The highest altitude where bandy has been played is in the capital of the Tajik autonomous province of Gorno-Badakhshan, Khorugh.[12]

Historical relationship with association football and ice hockey

As a precursor to ice hockey[13] bandy has influenced its development and history – mainly in European and former Soviet countries. While modern ice hockey was created in Canada, a game more similar to bandy was played initially, after British soldiers introduced the game in the late 19th century. At the same time as modern ice hockey rules were formalized in British North America (present day Canada), bandy rules were formulated in Europe. A cross between English and Russian bandy rules eventually developed, with the football-inspired English rules dominant, together with the Russian low border along most of the two sidelines, and this is the basis of the present sport since the 1950s.

Before Canadians introduced ice hockey into Europe in the early 20th century, "hockey" was another name for bandy,[14] and still is in parts of Russia and Kazakhstan.

With football and bandy being dominant sports in parts of Europe, it was common for sports clubs to have bandy and football sections, with athletes playing both sports at different times of the year. Some examples are English Nottingham Forest Football and Bandy Club (today known just as Nottingham Forest F.C.) and Norwegian Strømsgodset IF and Mjøndalen IF, with the latter still having an active bandy section. In Sweden, most football clubs which were active during the first half of the 20th century also played bandy. Later, as the season for each sport increased in time, it was not as easy for the players to engage in both sports, so some clubs came to concentrate on one or the other. Many old clubs still have both sports on their program.

Both bandy and ice hockey were played in Europe during the 20th century, especially in Sweden, Finland, and Norway.[15] Ice hockey became more popular than bandy in most of Europe mostly because it had become an Olympic sport, while bandy had not. Athletes in Europe who had played bandy switched to ice hockey in the 1920s to compete in the Olympics.[16][17] The smaller ice fields needed for ice hockey also made its rinks easier to maintain, especially in countries with short winters.[16][18] On the other hand, ice hockey was not played in the Soviet Union until the 1950s when the USSR wanted to compete internationally. The typical European style of ice hockey, with flowing, less physical play, represents a heritage of bandy.[19]

Names of the sport

The sport's English name comes from the verb "to bandy", from the Middle French bander ("to strike back and forth"), and originally referred to a 17th-century Irish game similar to field hockey. The curved stick was also called a "bandy".[20] The etymological connection to the similarly named Welsh hockey game of bando is not clear.

An old name for bandy is hockey on the ice; in the first rule books from England at the turn of the Century 1900, the sport is literally called "bandy or hockey on the ice".[21] Since the mid-20th century the term bandy is usually preferred to prevent confusion with ice hockey.

The sport is known as bandy in many languages though there are a few notable exceptions.[22] In Russian bandy is called "Russian hockey" (русский хоккей) or more frequently, and officially, "hockey with a ball" (xоккей с мячом) while ice hockey is called "hockey with a puck" (xоккей с шайбой) or more frequently just "hockey". If the context makes it clear that bandy is the subject, it as well can be called just "hockey". In Belarusian, Ukrainian and Bulgarian it is also called "hockey with a ball" (хакей з мячoм, хокей з м'ячем and хокей с топка respectively). In Slovak "bandy hockey" (bandyhokej) is the name. In Armenian, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Mongol and Uzbek, bandy is known as "ball hockey" (գնդակով հոկեյ, допты хоккей, топтуу хоккей, бөмбөгтэй хоккей and koptokli xokkey respectively). In Finnish the two sports are distinguished as "ice ball" (jääpallo) and "ice puck" (jääkiekko), as well as in Hungarian (jéglabda; jégkorong), although in Hungarian it is more often called "bandy" nowadays. In Estonian bandy is also called "ice ball" (jääpall). In Mandarin Chinese it is "bandy ball" (班迪球). In Scottish Gaelic the name is "ice shinty" (camanachd-deighe).[23] In old times shinty or shinney were also sometimes used in English for bandy.[8]

Games

Bandy is played on ice, using a single round ball. Two teams of 11 players each compete to get the ball into the other team's goal using sticks, thereby scoring a goal.[24]

The game is designed to be played on a rectangle of ice the same size as a football field. Bandy also has other rules that are similar to football. Each team has 11 players, one of whom is a goalkeeper. The offside rule is also employed.[24] A goal cannot be scored from a goal throw, but unlike football, a goal can be scored from a stroke-in or a corner stroke.[25] All free strokes are "direct" and allow a goal to be scored without another player touching the ball.

The team that has scored more goals at the end of the game is the winner. If both teams have scored an equal number of goals, then, with some exceptions, the game is a draw.[24]

The primary rule is that the players (other than the goalkeepers) may not intentionally touch the ball with their heads, hands or arms during play. Although players usually use their sticks to move the ball around, they may use any part of their bodies other than their heads, hands or arms and may use their skates in a limited manner. Heading the ball results in a five-minute penalty.[24]

In typical game play, players attempt to propel the ball toward their opponents' goal through individual control of the ball, such as by dribbling, passing the ball to a teammate, and taking shots at the goal, which is guarded by the opposing goalkeeper. Opposing players may try to regain control of the ball by intercepting a pass or through tackling the opponent who controls the ball. However, physical contact between opponents is limited. Bandy is generally a free-flowing game, with play stopping only when the ball has left the field of play, or when play is stopped by the referee. After a stoppage, play can recommence with a free stroke, a penalty shot or a corner stroke. If the ball has left the field along the sidelines, the referee must decide which team touched the ball last, and award a restart stroke to the opposing team, just like football's throw-in.[24]

The rules do not specify any player positions other than goalkeeper,[24] but a number of player specialisations have evolved. Broadly, these include three main categories: forwards, whose main task is to score goals; defenders, who specialise in preventing their opponents from scoring; and midfielders, who take the ball from the opposition and pass it to the forwards. Players in these positions are referred to as outfield players, to discern them from the single goalkeeper. These positions are further differentiated by which side of the field the player spends most time in. For example, there are central defenders, and left and right midfielders. The ten outfield players may be arranged in these positions in any combination (for example, there may be three defenders, five midfielders, and two forwards), and the number of players in each position determines the style of the team's play; more forwards and fewer defenders would create a more aggressive and offensive-minded game, while the reverse would create a slower, more defensive style of play. While players may spend most of the game in a specific position, there are few restrictions on player movement, and players can switch positions at any time. The layout of the players on the pitch is called the team's formation, and defining the team's formation and tactics is usually the prerogative of the team's manager(s).

Rules

- Overview

.jpg)

There are eighteen rules in official play, designed to apply to all levels of bandy, although certain modifications for groups such as juniors, veterans or women are permitted. The rules are often framed in broad terms, which allow flexibility in their application depending on the nature of the game.[24]

The Bandy Playing Rules can be found on the official website of the Federation of International Bandy,[24] and are overseen by the Rules and Referee Committee.

- Players and officials

Each team consists of a maximum of 11 players (excluding substitutes), one of whom must be the goalkeeper. A team of fewer than eight players may not start a game. Goalkeepers are the only players allowed to play the ball with their hands or arms, and they are only allowed to do so within the penalty area in front of their own goal.[26]

Though there are a variety of positions in which the outfield (non-goalkeeper) players are strategically placed by a coach, these positions are not defined or required by the rules of the game.[24]

The positions and formations of the players in bandy are virtually the same as the common association football positions and the same terms are used for the different positions of the players. A team usually consists of defenders, midfielders and forwards. The defenders can play in the form of centre-backs, full-backs and sometimes wing-backs, midfielders playing in the centre, attacking or defensive, and forwards in the form of centre forward, second strikers and sometimes a winger. Sometimes one player is also taking up the role of a libero.

Any number of players may be replaced by substitutes during the course of the game. Substitutions can be performed without notifying the referee and can be performed while the ball is in play. However, if the substitute enters the ice before his teammate has left it, this will result in a five-minute ban. A team can bring at the most four substitutes to the game and one of these is likely to be an extra goalkeeper.[26]

A game is officiated by a referee, the authority and enforcer of the rules, whose decisions are final. The referee may have one or two assistant referees. A secretary outside of the field often takes care of the match protocol.[24]

- Equipment

The basic equipment players are required to wear includes a pair of Bandy skates, a helmet, a mouth guard and, in the case of the goalkeeper, a face guard.

The teams must wear uniforms that make it easy to distinguish the two teams. The goal keeper wears distinct colours to single him out from his or her teammates, just as in football. The skates, sticks and any tape on the stick must be of another colour than the bandy ball, which shall be orange or cerise.[24]

In addition to the aforementioned, various protections are used to protect knees, elbows, genitals and throat. The pants and gloves may contain padding.

- The bandy stick

The stick used in bandy is an essential part of the sport. It should be made of an approved material such as wood or a similar material and should not contain any metal or sharp parts which can hurt the surrounding players. Sticks are crooked and are available in five angles, where 1 has the smallest bend and 5 has the most. Bend 4 is the most common size in professional bandy. The bandy stick should not have similar colours to the ball, such as orange or pink; it should be no longer than 127 centimetres (50 in), and no wider than 7 centimetres (2.8 in).[27]

- Field

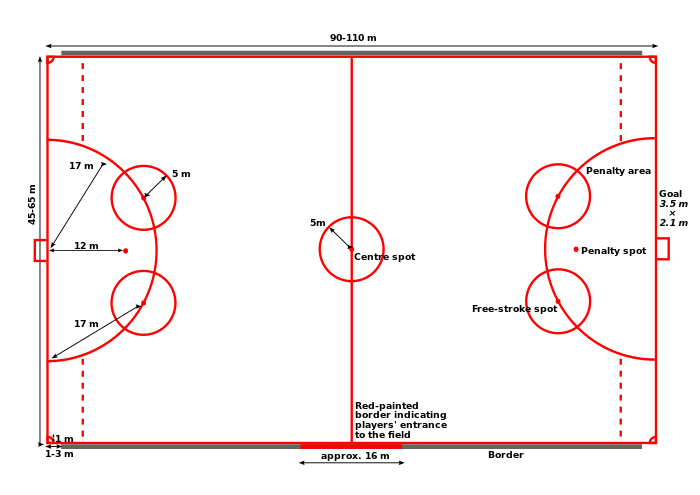

A bandy field is 45–65 metres (148–213 ft) by 90–110 metres (300–360 ft), a total of 4,050–7,150 square metres (43,600–77,000 sq ft), or about the same size as a football pitch and considerably larger than an ice hockey rink. Along the sidelines a 15 cm (6 in) high border (vant, sarg, wand, wall) is placed to prevent the ball from leaving the ice. It should not be attached to the ice, to glide upon collisions, and should end 1–3 metres (3 ft 3 in–9 ft 10 in) away from the corners.

Centered at each shortline is a 3.5 m (11 ft) wide and 2.1 m (6 ft 11 in) high goal cage and in front of the cage is a half-circular penalty area with a 17 m (56 ft) radius. A penalty spot is located 12 metres (39 ft) in front of the goal and there are two free-stroke spots at the penalty area line, each surrounded by a 5 m (16 ft) circle.

A centre spot with a circle of radius 5 m (16 ft) denotes the center of the field. A centre-line is drawn through the centre spot parallel with the shortlines.

At each of the corners, a 1 m (3 ft 3 in) radius quarter-circle is drawn, and a dotted line is painted parallel to the shortline and 5 metres (16 ft) away from it without extending into the penalty area. The dotted line can be replaced with a 0.5-metre (1 ft 8 in) long line starting at the edge of the penalty area and extending towards the sideline, 5 metres (16 ft) from the shortline.[24]

- Duration and tie-breaking measures

A standard adult bandy match consists of two periods of 45 minutes each, known as halves. Each half runs continuously, meaning the clock is not stopped when the ball is out of play; the referee can, however, make allowance for time lost through significant stoppages as described below. There is usually a 15-minute half-time break. The end of the match is known as full-time.[24]

The referee is the official timekeeper for the match, and may make an allowance for time lost through substitutions, injured players requiring attention, or other stoppages. This added time is commonly referred to as stoppage time or injury time, and must be reported to the match secretary and the two captains. The referee alone signals the end of the match.[24]

If it is very cold or if it is snowing, the match can be broken into thirds of 30 minutes each. At the extremely cold 1999 World Championship some matches were played in four periods of 15 minutes each and with extra long breaks in between. In the World Championships the two halves can be 30 minutes each for the nations in the B division.

In league competitions games may end in a draw, but in some knockout competitions if a game is tied at the end of regulation time it may go into extra time, which consists of two further 15-minute periods. If the score is still tied after extra time, the game will be replayed. As an alternative, the extra two times 15-minutes may be played as "golden goal" which means the first team that scores during the extra-time wins the game. If both extra periods are played without a scored goal, a penalty shootout will settle the game. The teams shoot five penalties each and if this doesn't settle the game, the teams shoot one more penalty each until one of them misses and the other scores.

- Ball in and out of play

Under the rules, the two basic states of play during a game are ball in play and ball out of play. From the beginning of each playing period with a stroke-off (a set strike from the centre-spot by one team) until the end of the playing period, the ball is in play at all times, except when either the ball leaves the field of play, or play is stopped by the referee. When the ball becomes out of play, play is restarted by one of six restart methods depending on how it went out of play:

- Stroke-off

- Goal-throw

- Corner stroke

- Free-stroke

- Penalty shot

- Face-off

If the time runs out while a team is preparing for a free-stroke or penalty, the strike should still be made but it must go into the goal by one shot to count as a goal. Similarly, a goal made via a corner stroke should be allowed, but it must be executed using only one shot in addition to the strike needed to put the ball in play.[24]

- Free-strokes and penalty shots

Free-strokes can be awarded to a team if a player of the opposite team breaks any rule, for example, by hitting with the stick against the opponent's stick or skates. Free-strokes can also be awarded upon incorrect execution of corner-strikes, free-strikes, goal-throws, and so on. or the use of incorrect equipment, such as a broken stick.[24]

Rather than stopping play, the referee may allow play to continue when its continuation will benefit the team against which an offence has been committed. This is known as "playing an advantage". The referee may "call back" play and penalise the original offence if the anticipated advantage does not ensue within a short period of time, typically taken to be four to five seconds. Even if an offence is not penalised because the referee plays an advantage, the offender may still be sanctioned (see below) for any associated misconduct at the next stoppage of play.[24]

If a defender violently attacks an opponent within the penalty area, a penalty shot is awarded. Certain other offences, when carried out within the penalty area, result in a penalty shot provided there is a goal situation. These include a defender holding or hooking an attacker, or blocking a goal situation with a lifted skate, thrown stick or glove and so on. Also, the defenders (with the exception of the goal-keeper) are not allowed to kneel or lie on the ice. The final offences that might mandate a penalty shot are those of hitting or blocking an opponent's stick or touching the ball with the hands, arms, stick or head. If any of these actions is carried out in a non-goal situation, they shall be awarded with a free-stroke from one of the free-stroke spots at the penalty area line. A penalty shot should always be accompanied by a 5 or 10 minutes penalty (see below). If the penalty results in a goal, the penalty should be considered personal meaning that a substitute can be sent in for the penalised player. This does not apply in the event of a red card (see below).[24]

- Warnings and penalties

A ten-minute penalty is indicated through the use of a blue card and can be caused by protesting or behaving incorrectly, attacking an opponent violently or stopping the ball incorrectly to get an advantage.

The third time a player receives a penalty, it will be a personal penalty, meaning he or she will miss the remainder of the match. A substitute can enter the field after five or ten minutes. A full game penalty can be received upon using abusive language or directly attacking an opponent and means that the player can neither play nor be substituted for the remainder of the game. A match penalty is indicated through the use of a red card.

- Offside

The offside rule effectively limits the ability of attacking players to remain forward (i.e. closer to the opponent's goal-line) of the ball, the second-to-last defending player (which can include the goalkeeper), and the half-way line. This rule is in effect just like that of soccer.[24]

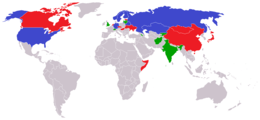

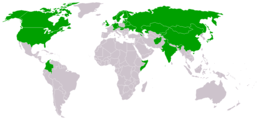

International

International federation

The Federation of International Bandy (FIB) has had 33 members at most. Currently, 27 members are a part.[28] Formed in 1955, the name was changed from International Bandy Federation in 2001 after the International Olympic Committee approved it as a so-called "recognized sport"; the abbreviation "IBF" was already used by another recognized sports federation. In 2004, FIB was fully accepted by IOC.

FIB is now a member of Association of IOC Recognised International Sports Federations.

World Championships

The Bandy World Championship for men is arranged by the FIB and was first held in 1957. It was held every two years starting in 1961, and every year since 2003. Currently the record number of countries participating in the World Championships is twenty (2019). Since the number of countries playing bandy is not large, every country which can set up a team is welcome to take part in the World Championship. The quality of the teams varies; however, with only six nations, Sweden, the Soviet Union, Russia, Finland, Norway, and Kazakhstan, having won medals (allowing for the fact that Russia's team took over from the Soviet Union in 1993). Finland won the 2004 world championship in Västerås, Sweden, while all other championships have been won by Sweden, the Soviet Union and Russia.

In February 2004, Sweden won the first World Championship for women, hosted in Finland, without conceding a goal. In the 2014 women's World Championship Russia won, for the first time toppling the Swedes from the throne. In 2016 Sweden took the title back. In 2018 the tournament was played in a totally Asian country for the first time when Chengde in China hosted it.[29][30]

The same goes for the men's tournament (the area north and west of the Ural River is located in Europe, thus Kazakhstan is a transcontinental country), when Harbin hosted the 2018 Division B tournament.

There are also Youth Bandy World Championships in different age groups for boys and young men and in one age group for girls. The oldest group is the under 23 championship, Bandy World Championship Y-23.

Olympic Movement

Bandy is recognized by the International Olympic Committee, and was played as a demonstration sport at the 1952 Winter Olympics in Oslo. However, it has yet to officially be played at the Olympics.

FIB president Boris Skrynnik lobbied for Bandy to be included in the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, given Russia's prominence in the sport.[31] Members of the Chinese Olympic Committee were present at the 2017 world championships to meet with Skrynnik about the possibility of considering the sport for the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing.[32][33] However, in 2018 it was announced no new sports would be added for 2022.[34]

Compared with the seven Winter Olympic sports, bandy's popularity across the globe is considered by the International Olympic Committee to have a, "gap between popularity and participation and global audiences", which is a roadblock into future Olympic inclusion.

Asian Winter Games

At the 2011 Asian Winter Games, open to members of the Olympic Council of Asia, men's bandy was included for the first time. Three teams contested the inaugural competition, and Kazakhstan won the gold medal. President Nursultan Nazarbayev attended the final.[35][36]

There was no bandy competition at the 2017 Asian Winter Games in Japan.

Winter Universiade

Bandy made its debut at the Winter Universiade during the 2019 Games. Originally a six team tournament for men and a four team tournament for women were planned to be held.[37] However, later China withdrew from the men's tournament and was supposed be replaced by Belarus.[38] Since that did not happen either, participating teams among women were Russia, Sweden, Norway and USA, while among men Russia, Sweden, Norway, Finland and Kazakhstan.

There is a chance for participation also in 2023. In fact International University Sports Federation expects it to happen.[39]

World Cup

The World Championships should not be confused with the annual World Cup in Ljusdal, Sweden, which has been played annually since the 1970s and is the biggest bandy tournament for elite level club teams. It is played indoors in Sandviken since 2009 because Ljusdal has no indoor arena. It is expected to return to Ljusdal once an indoor arena has been built. World Cup matches are played day and night, and the tournament is played in four days in late October. The teams participating are mostly, and some years exclusively, from Sweden and Russia, which has the two best leagues in the world.

Since 2007, there is also a Bandy World Cup Women for women's teams.[40]

Varieties

Rink bandy is a variety played on an ice hockey-size rink.[41] It was in the programme of the 2012 European Company Sports Games.[42] Some FIB countries don't have a large ice surface and only play rink bandy at home; this includes most of the World Championships Group B participants.

Countries

- China

The China Bandy Federation was set up in 2014 and China has since then participated in a number of world championship tournaments, with men's, women's and youth teams. China Bandy is mainly financed by private resources. The development of the sport in China is supported by the Harbin Sport University.

- England

The first recorded games of bandy on ice took place in The Fens during the great frost of 1813–1814, although it is probable that the game had been played there in the previous century. Bury Fen Bandy Club[43][44] from Bluntisham-cum-Earith, near St Ives, was the most successful team, remaining unbeaten until the winter of 1890–1891. Charles G Tebbutt of the Bury Fen bandy club was responsible for the first published rules of bandy in 1882, and also for introducing the game into the Netherlands and Sweden, as well as elsewhere in England where it became popular with cricket, rowing and hockey clubs. Tebbutt's home-made bandy stick can be seen in the Norris Museum in St Ives.

The first Ice Hockey Varsity Matches between Oxford University and Cambridge University were played to bandy rules, even if it was called hockey on ice at the time.

England won the European Bandy Championships in 1913,[45] but that turned out to be the grand finale, and bandy is now virtually unknown in England. In March 2004, Norwegian ex-player Edgar Malman invited two big clubs to play a rink bandy exhibition game in Streatham, London. Russian Champions and World Cup Winner Vodnik met Swedish Champions Edsbyns IF in a match that ended 10–10. In 2010 England became a Federation of International Bandy member. The federation is based in Cambridgeshire, the historical heartland.[46]

The England Bandy Federation, now the Great Britain Bandy Federation, was set up on 2 January 2017 at a meeting held in the historic old skaters public house, the Lamb and Flag in Welney in Norfolk, England, replacing the Bandy Federation of England which was founded in 2010. President is Rev Lyn Gibb-de Swarte of Littleport and past resident of Streatham in south west London, where she was chair of the Streatham ice speed club, ice hockey club and of the association of ice clubs. Vice Presidents; Simon Seager and Les Mead. Chair is Andrew Hutchinson. Treasurer is Tammy Nichol Twallin . General Secretary, Fixtures and Minutes Secretary, Cathy Gibb-de Swarte. Participation Officer, Anders Gidrup. Recruitment UK is Oscar Gillingham Aukner. They are all busy promoting the sport for all and will be instituting rink bandy around the country. The president is the project director of the Littleport Ice Stadium Project and plans are already drawn for a 400 metres indoor speed skating oval and an inner ice pad 100 × 60 metres bandy pitch. In September 2017, the federation decided to widen its territory to all of the United Kingdom and changed its name to Great Britain Bandy Federation.[47] Great Britain entered a national team in the 2019 World Championships Group B in January and undefeated up to the final, won the silver medal in their final match against Estonia.

- Estonia

Bandy was played in Estonia in the 1910s to 1930s and the country had a national championship for some years. The national team played friendlies against Finland in the 1920s and '30s. The sport was played sporadically during Soviet occupation 1944–1991. It has since then become more organised again, partly through exchange with Finnish clubs and enthusiasts. As of 2018, Estonia takes part in both the men's and the Women's Bandy World Championship.

- Finland

Bandy was introduced to Finland from Russia in the 1890s. Finland has been playing bandy friendlies against Sweden and Estonia since its independence in 1917.

The first Finnish national championships were held in 1908 and was the first national Finnish championship held in any team sport. National champions have been named every year except for three years in the first half of the 20th Century when Finland was at war. The top national league is called Bandyliiga and is semi-professional. The best players often go fully professional by being recruited by clubs in Sweden or Russia.[48]

Finland was an original member of the Federation of International Bandy and is the only country beside Russia/Soviet Union and Sweden to have won a Bandy World Championship, which it did in 2004.

- Germany

Bandy was played in Germany in the early 20th century, including by Crown Prince Wilhelm,[49] but the interest died out in favour of ice hockey. Leipziger Sportclub had the best team and was also last to give bandy up. The sport was reintroduced in the 2010s, with the German Bandy Association being founded in 2013.[50]

- Kazakhstan

Bandy has a long history in many parts of the country and it used to be one of the most popular sports in Soviet times. However, after independence it suffered a rapid decline in popularity and only remained in Oral (often called by the Russian name, Uralsk), where the country's only professional club Akzhaiyk is located. They are competing in the Russian second tier division, the Supreme League. Recently bandy has started to gain popularity again outside of Oral, most notably in Petropavl[51] and Khromtau. Those were for example the three Kazakh cities which at the Youth-17 World Championship 2016 had players in the team.[52] The capital Nur-Sultan has hosted national youth championships in rink bandy.[53] as well as championships in traditional eleven-a-side bandy.[54] The former capital Almaty has in recent years hosted both the Asian Winter Games (with bandy on the program) as well as the Bandy World Championship in which Kazakhstan finished 3rd. Plans are made to reinvigorate the bandy section of the club Dynamo Almaty, who won the Soviet Championships in 1977 and 1990 as well as the European Cup in 1978. The Asian Bandy Federation also has its headquarters in Almaty. Since a few years the state is supporting bandy. Medeu in Almaty is the only arena with artificial ice. A second arena in Almaty was built for the World Championship 2012, but it was taken down afterwards. Stadion Yunost in Oral[55] was supposed to get artificial ice for the 2017–18 season.[56] It got delayed but in 2018 it was officially ready for use.[57]

- Mongolia

The national team took a silver medal at the 2011 Asian Winter Games, which led to being chosen as the best Mongolian sport team of 2011.[58] Mongolia was proud to win the bronze medal of the B division at the 2017 Bandy World Championship[59] after which the then President of Mongolia, Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj, held a reception for the team.[60]

- Netherlands

Bandy was introduced to the Netherlands in the 1890s by Pim Mulier and the sport became popular. However, in the 1920s, the interest turned to ice hockey, but in contrast to other countries in central and western Europe, the sport has been continuously played in the Netherlands and since the 1970s, the country has become a member of FIB and games have been more formalised again.[61] The national team started to compete at the WCS in 1991. However, without a proper venue, only rink bandy is played within the country. The national governing body is the Bandy Bond Nederland.[62]

- Norway

Bandy was introduced to Norway in the 1910s. The Swedes contributed largely, and clubs sprang up around the capital of Oslo. Oslo, including neighbouring towns, is still today the region where bandy enjoys most popularity in Norway.

In 1912 the Norwegians played their first National Championship, which was played annually up to 1940. During WWII, illegal bandy was played in hidden places in forests, on ponds and lakes. In 1943, −44 and −45, illegal championships were held. In 1946 legal play resumed and still goes on. After WWII the number of teams rose, as well as attendance which regularly were in the thousands, but mild winters in the 1970s and 80s shrunk the league, and in 2003 only five clubs (teams) fought out the 1st division with low attendance numbers and little media coverage.

In recent years, the number of artificially frozen pitches have increased in Norway, and more sports clubs have reinvigorated their bandy sections with new men's and youth teams. Because of this, as well as an increase of Swedish players in Norway, the competitiveness of the game has risen, especially in the first division Eliteserien. The adult men's game in Norway today consists of Eliteserien with eight teams, as well as three lower divisions. Bandy in Norway has also started to spread geographically, but some clubs in apart locations in the 3rd division only have access to ice hockey rinks and therefore play rink bandy for home games. Compared to the past, attendance is still fairly low, but important Eliteserien matches can attract around 1000 spectators.

- Russia

In Russia bandy is known as hockey with a ball or simply Russian hockey. A similar game became popular among the Russian nobility in the early 1700s, with the imperial court of Peter the Great playing a predecessor of modern bandy on Saint Petersburg's frozen Neva river. Russians played this game using ordinary footwear, with sticks made out of juniper wood, only later were skates introduced. It was only in the second half of the 19th century that bandy became popular among the masses throughout the Russian Empire. Traditionally the Russians used a longer skate blade than other nations, giving them the advantage of skating faster. However, they would find it more difficult to turn quickly. A bandy skate has a longer blade than a hockey skate, and the "Russian skate" is even longer.

When the Federation of International Bandy was formed in 1955, with the Soviet Union as one of its founding members, the Russians largely adopted the international rules of the game developed in England in the 19th century, with one notable exception. The other countries adopted the border.

Bandy is considered a national sport in Russia[63] and is the only discipline to have official support of the Russian Orthodox Church.[64]

The Russian Bandy Super League is played every year and the winner in the final becomes Russian champion. The Russian Cup has been played annually (except for just some years) since 1937.

After the victory in the 2016 World Championship, the fourth in a row, President Putin received four players of the national team, Head Coach and Vice-President of the Russian Bandy Federation Sergey Myaus, the Russian Bandy Federation as well as Federation of International Bandy President Boris Skrynnik in The Kremlin. He talked, among other things, about the need to give more support to Russian bandy.[65] It was the first time a head of state had accepted a meeting to talk about Russian bandy. Attending the meeting were also Minister of Sport, Tourism and Youth policy Vitaly Mutko and presidential adviser Igor Levitin.[66] The month after, Igor Levitin held a follow-up meeting.[67]

- Sweden

Bandy was introduced to Sweden in 1895. The Swedish royal family, noblemen and diplomats were the first players. Swedish championships for men have been played annually since 1907. In the 1920s students played the game and it became a largely middle class sport. After Slottsbrons IF won the Swedish championship in 1934 it became popular amongst workers in the smaller industrial towns and villages. Bandy remains the main sport in many of these places.

Bandy in Sweden is famous for its "culture" – both playing bandy and being a spectator requires great fortitude and dedication. A "bandy briefcase" is the classic accessory for spectating – it is typically made of brown leather, well worn and contains a warm drink in a thermos and/or a bottle of liquor.[68] Bandy is most often played at outdoor arenas during winter time, so the need for spectators to carry flasks or thermoses of 'warming' liquid like glögg is a natural effect.

A notable tradition is "annandagsbandy", bandy games played on Saint Stephen's Day, which for many Swedes is an important Christmas season tradition and always draws bigger crowds than usual. Games traditionally begin at 1:15 pm.[69]

The final match for the Swedish Championship is played every year on the third Saturday of March. From 1991 to 2012, it was played at Studenternas Idrottsplats in Uppsala, often drawing crowds in excess of 20,000. The reason the play-off match was set in Uppsala is because of IFK Uppsala's success in the beginning of the 20th century. IFK Uppsala won 11 titles in the Swedish Championships between 1907 and 1920, which made them the most successful bandy club in the entire country. Now, however, the record is held by Västerås SK. A contributing factor was the poor quality of the ice at Söderstadion, where the finals were held from 1967 to 1989.

In 2013 and 2014 the final was played indoors in Friends Arena, the national stadium for football in Solna, Stockholm, with a retractable roof and a capacity of 50 000. The first final at Friends Arena in 2013 drew a record crowd of 38,474 when Hammarby IF Bandy, after ending up in second place in six finals during the 2000s, won their second title. Due to declining attendance since, for 2015 through 2017 Tele2 Arena in southern Stockholm was chosen as a new venue. However, the new indoor venue failed to attract much more than half of the total capacity. In May 2017 it was announced that the finals will again be held at Studenternas IP in Uppsala from 2018 to 2021.

- Switzerland

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Switzerland had become a popular place for winter vacations and people went there from all over Europe. Winter sports like skiing, sledding and bandy was played in Geneva and other towns.[70] Students from Oxford and Cambridge went to Switzerland to play each other – the predecessor of the recurring Ice Hockey Varsity Match was a bandy match played in St. Moritz in 1885. This popularity for Swiss venues of winter sport may have been a reason, the European Championship was held there in 1913.

Bandy has mainly been played as a recreational sport in Switzerland in the last decade, but a Swiss national team took part in the 2018 Women's Bandy World Championship.

- Ukraine

Bandy was played in Ukraine when it was part of the Soviet Union. After independence in 1991, it took some years before organised bandy formed again, but Ukrainian champions have been named annually since 2012.

- United States

Bandy has been played in the United States since around 1980. The sport is centered in Minnesota, with very few teams based elsewhere.[71] The United States national bandy team has participated in the Bandy World Championships since 1985 and is also regularly playing friendly matches against Canada.

United States bandy championships have been played annually since the early 1980s, but the sport is not widely covered by American sports media.

- National Bandy Federations;

- Belarus – Беларуская федэрацыя хакея з мячaм (Belarusian Bandy Federation)

- Canada – Canada Bandy[72]

- People's Republic of China – China Bandy Federation

- Estonia – Eesti Jääpalliliit[73]

- Finland – Finland's Bandy Association[74]

- Hungary – Hungarian Bandy Federation[75]

- India – Bandy Federation of India

- Italy – Federazione Italiana Bandy

- Japan – Japan Bandy Federation[76]

- Kazakhstan – Kazakhstan Bandy Federation

- Kyrgyzstan – Bandy Federation of Kyrgyzstan

- Latvia – Latvijas Bendija Federācija[77]

- Mongolia – Bandy Federation of Mongolia

- Netherlands – Nederlandse Roller Sport and Bandy Bond[78]

- Norway – Norges Bandyforbund[79]

- Russia – Федерация хоккея с мячом России (Russian Bandy Federation)[80]

- Somalia – Somali National Bandy Association[81]

- Sweden – Svenska Bandyförbundet[82]

- Switzerland – Federation of Swiss Bandy

- Ukraine – Українськa Федерація хокею з м'ячем та рінк-бенді (Ukrainian Bandy and Rink bandy Federation)[83]

- United States – American Bandy Association[84]

See also

References

- Arlott, John, ed. (1975). "Bandy". The Oxford Companion to Sports & Games. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- "Edsbyn Sandviken SM – Final in Upssala". YouTube. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- "Bandy versus the 50 Olympic Winter Games Disciplines". 4 December 2015. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- "Bandy destined for the Olympic Winter Games!". Federation of International Bandy. 21 October 2016. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- Bandyportföljen magazine, no. 4 20017/18, pp. 12-13

- Butler, Nick (4 February 2018). "New sports face struggle to be added to Winter Olympic Games programme, IOC warn". Insidethegames.biz. Dunsar Media. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- Bandyns historia http://www.skiro-navelsjo.se/ (in Swedish; read on 2 December 2017)

- Heathcote, John Moyer; Tebbutt, C. G.; Buck, Henry A.; Kerr, John; Hake, Ormond; Witham, T. Maxwell (9 January 1892). "Skating". London : Longmans, Green and Co. – via Internet Archive.

- "Photo of Bury Fen Bandy Club". Web.archive.org. 28 October 2009. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "Svenska Bandyförbundet, bandyhistoria 1875–1919". Iof1.idrottonline.se. 1 February 2013. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- "The Finnish Bandy Federation, in English". Finnish Bandy Association. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- "Google Translate".

- "Hockey in Montreal since the 19th Century | Thematic Tours | Musée McCord Museum". Mccord-museum.qc.ca. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- Nordisk Familjebok 10 Hassle-Infektera, Förlagshuset Norden AB, Malmö 1952, "Hockey", column 386

- Nordisk Familjebok 2 Asura-Bidz, Förlagshuset Norden AB, Malmö 1951, "Bandy", columns 324–326

- Eric Converse (17 May 2013). "Bandy: The Other Ice Hockey". The Hockey Writers. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- E.g. in the Netherlands, see Arnout Janmaat (7 March 2013). "120 jaar bandygeschiedenis in Nederland (1891–2011)" (PDF). p. 10. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- Waldemar Ingdahl (12 November 2008). "Bandy – ice hockey in Sweden goes big in Europe". Café Babel. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- Joe Posnanski (14 February 2014). "Russians no longer mesmerize with brilliant hockey but golden feeling is there". NBC Sports Pro Hockey Talk. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary, "bandy"". Online Etymology Dictionary. 2011. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- Arne Argus: "Bandy i 100 år", 2002, ISBN 91-631-3005-X, p. 36 (in Swedish)

- For the foreign names mentioned in this section, see the language links to the left in this article.

- "Am Faclair Beag - Scottish Gaelic Dictionary". www.faclair.com.

- "Bandy Playing Rules" (PDF). Federation of International Bandy. 1 September 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- "Bandy Glossary". Fuzilogik.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2010. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- Ninh.co.uk: "The Rules of Bandy - EXPLAINED!", retrieved 14 October 2017

- "Federation of International Bandy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- "Members - Federation of International Bandy". www.worldbandy.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2017. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- "Google Translate".

- "Google Translate".

- "It's Not Hockey, It's Bandy". The New York Times. 29 January 2010.

- "Bandy has chances to be included into 2022 Winter Olympics - FIB President". TASS. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- "Bandy: How Sweden's little known sport is winning fans". The Local. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 25 September 2016.

- Butler, Nick (7 February 2018). "IOC confirm no new sports will be added to Beijing 2022 programme". Insidethegames.biz. Dunsar Media. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- "Google Translate". translate.google.co.uk.

- "Image of President Nursultan Nazarbayev attending the 2011 Asian Winter Games final". sports.ru.

- "Krasnoyarsk 2019 Winter Universiade - The Gateway to the Olympics" (PDF). www.bandyforbundet.no/. 29 June 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- "Google Translate". Translate.google.co.uk. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- "FISU рассчитывает, что хоккей с мячом будет представлен в программе Универсиады-2023". Tass.ru. 2 March 2019. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- "Bandysidan". Bandysidan.nu. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- "Official rules, bandy and rink bandy". Internationalbandy.com. 23 September 2009. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "Rinkbandy – Visit Sodra Dalarna". Visitsodradalarna.se. 24 May 2011. Archived from the original on 28 April 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- "Club badge". Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- "Photo of Bury Fen Bandy Club". Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "England in European Bandy Championships". Web.archive.org. 28 October 2009. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "Members". 16 November 2015. Archived from the original on 17 February 2016.

- "Home Page". gbbandyfederation.uk. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- "The Finnish Bandy Federation, in English". Finnish Bandy Association. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- "Image of Crown Prince Wilhelm leisurely playing". Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- "Deutscher Bandy-Bund - DBB". bandy-bund.de.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Информация о команде Юношеская сборная Казахстана (игроки до 17 лет) – Сборные команды – Федерация хоккея с мячом России". rusbandy.ru.

- "Google Translate". translate.google.co.uk.

- INFORM.KZ. "Хоккей с мячом: Сборная ЗКО стала чемпионом Казахстана (ФОТО)". www.inform.kz.

- "Информация о стадионе "Юность", Уральск – Реестр – Федерация хоккея с мячом России".

- "Каток в Уральске сдадут до конца 2017 года - Архив новостей - Федерация хоккея с мячом России". rusbandy.ru.

- 0:00 / 0:00. "TDK-42". Tdk42.kz. Retrieved 10 June 2019.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- "Mongolia NOC announces sports press awards". Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- The UB Post: "Ice sports facility is more important than prizes, says coach A.mergen", by Tungalag Baatar – February 7, 2017, retrieved 30 September 2017

- Baatar, Tungalag. "President praises national bandy team – The UB Post". archive-it.org. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017.

- Arnout Janmaat (7 March 2013). "120 jaar bandygeschiedenis in Nederland" (PDF). Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- "Bandybond Nederland -". bandybond.nl.

- "Russian bandy players blessed for victory at world championship in Kazan". Tatar-Inform. 21 January 2011. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- "Google Translate".

- "Meeting with Russia's national bandy team". President of Russia.

- "Google Translate". translate.google.com.

- "Google Translate". translate.google.com.

- Sundberg, Ingrid (10 November 2006). "Bandyportföljens tid är här". Folket (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- Rosqvist, Berndt (22 December 2003). "Festligt och fullsatt på stora bandydagen". Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 18 April 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- "Antique Bandy / Shinty Game – Caux-Jeu de Hockey – 1906 – Geneve – HockeyGods".

- https://www.usabandy.com

- "Welcome to Canada Bandy". Canadabandy.ca. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- "Pealeht". Hot.ee. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- "Suomen jääpalloliitto". Finbandy.fi. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- "Hungarian Bandy Federation". Bandy.hu. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- "日本バンディ連盟:トップページ". J-bandy.jp. 15 November 2011. Archived from the original on 3 December 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- Aigars Krjanins. "Latvijas Bendija Federācija". Bandy.lv. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- "nrbb.nl". Ndparking.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- "Norges Bandyforbund – Bandy". Bandyforbundet.no. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- "Федерация хоккея с мячом России". Rusbandy.ru. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- SomaliaBandy2014 (24 August 2013). "Somalia Bandy 2014". Somalia Bandy 2014. Archived from the original on 21 January 2014. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- "Svenska Bandyförbundet". svenskbandy.se. Archived from the original on 27 March 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- "Українська Федерація хокею з м'ячем і рінк-бенді". Ukrbandy.org.ua. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- "American Bandy Association". Usabandy.com. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

Bibliography

- The Earl of Suffolk and Berkshire Hedley Park and Aflalo, F.G. Bandy (includes definition and rules), pp. 71–72, 1897. Published by Lawrence & Bullen, Ltd., 16 Henrietta St., Covent Garden, London.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bandy. |

- "What is Bandy?". Archived from the original on 27 October 2009. Retrieved 10 November 2011.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) – History and rules of Bandy.

- Bandy at Curlie

- Federation of International Bandy

- Bandysidan links – One of the most extensive link directories about bandy

- Klein, Jeff Z. "It's Not Hockey, It's Bandy," The New York Times, Friday, 29 January 2010.

- Goalwire statistics for bandy

- Tebbutt, C.G (1892). "Chapter XIII: Bandy". Skating. Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 429–441. OL 7132924M. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- Ninh.co.uk: "The Rules of Bandy - EXPLAINED!" (video), retrieved 14 October 2017