Competence (human resources)

Competence is the set of demonstrable characteristics and skills that enable, and improve the efficiency or performance of a job. The term "competence" first appeared in an article authored by R.W. White in 1959 as a concept for performance motivation. In 1970, Craig C. Lundberg defined the concept in "Planning the Executive Development Program". The term gained traction when in 1973, David McClelland wrote a seminal paper entitled, "Testing for Competence Rather Than for Intelligence". It has since been popularized by Richard Boyatzis and many others, such as T.F. Gilbert (1978) who used the concept in relationship to performance improvement. Its use varies widely, which leads to considerable misunderstanding.

Some scholars see "competence" as a combination of practical and theoretical knowledge, cognitive skills, behavior and values used to improve performance; or as the state or quality of being adequately or well qualified, having the ability to perform a specific role. For instance, management competency might include systems thinking and emotional intelligence, and skills in influence and negotiation.

Studies on competency indicate that competency covers a very complicated and extensive concept, and different scientists have different definitions of competency. In 1982, Zemek conducted a study on the definition of competence. He interviewed several specialists in the field of training to evaluate carefully what makes competence. After the interviews, he concluded: "There is no clear and unique agreement about what makes competency."

Here are several definitions of competency by various researchers:

- Hayes (1979): Competences generally include knowledge, motivation, social characteristic and roles, or skills of one person in accordance with the demands of organizations of their clerks.

- Boyatzis (1982): Competence lies in the individual's capacity which superposes the person's behavior with needed parameters as the results of this adaptation make the organization to hire him.

- Albanese (1989): Competences are individual's characteristics which are used to effect on the organization's management.

- Woodruff (1991): Competence is a combination of two topics of personal competence and merit at work. Personal merit is a concept which refers to the dimensions of artificial behavior in order to show the competence performance and merit at work depends on the competences of the person in his field.

- Mansfield (1997): The personal specifications which effect on a better performance are called competence.

- Standard (2001) ICB (IPMA Competence Baseline): Competence is a group of knowledge, personal attitudes, skills and related experiences which are needed for the person's success.

- Rankin (2002): A collection of behaviors and skills which people are expected to show in their organization.

- Unido (United Nations Industrial Development Organization) (2002): Competence is defined as knowledge, skill and specifications which can cause one person to act better, not considering his special proficiency in that job.

- Industrial Development Organization of United States (2002): Competences are a collection of personal skills related to knowledge and personal specifications which can make competence in people without having practices and related specialized knowledge.

- CRNBC (College Of Registered Nurses Of British Columbia) (2009): Competences are a collection of knowledge, skills, behavior and power of judging which can cause competence in people without having enough practice and specialized knowledge.

- Hay group (2012): Measurable characteristics of a person which are related to efficient actions at work, organization and special culture.

- The ARZESH Competency Model (2018): Competency is a series of knowledge, abilities, skills, experiences and behaviors, which leads to the effective performance of individual's activities. Competency is measurable and could be developed through training. It is also breakable into the smaller criteria.[1]

Competency is also used as a more general description of the requirements of human beings in organizations and communities.

If someone is able to do required tasks at the target level of proficiency, they are "competent" in that area.

Competency is sometimes thought of as being shown in action in a situation and context that might be different the next time a person has to act. In emergencies, competent people may react to a situation following behaviors they have previously found to succeed. To be competent a person would need to be able to interpret the situation in the context and to have a repertoire of possible actions to take and have trained in the possible actions in the repertoire, if this is relevant. Regardless of training, competency would grow through experience and the extent of an individual's capacity to learn and adapt. However, research has found that it is not easy to assess competencies and competence development.[2]

Overview

Competency has different meanings, and remains one of the most diffuse terms in the management development sector, and the organizational and occupational literature.[3]

Competencies are also what people need to be successful in their jobs. Job competencies are not the same as job task. Competencies include all the related knowledge, skills, abilities, and attributes that form a person's job. This set of context-specific qualities is correlated with superior job performance and can be used as a standard against which to measure job performance as well as to develop, recruit, and hire employees.

Competencies and competency models may be applicable to all employees in an organization or they may be position specific. Identifying employee competencies can contribute to improved organizational performance. They are most effective if they meet several critical standards, including linkage to, and leverage within an organization's human resource system.

Core competencies differentiate an organization from its competition and create a company's competitive advantage in the marketplace. An organizational core competency is its strategic strength.

Competencies provide organizations with a way to define in behavioral terms what it is that people need to do to produce the results that the organization desires, in a way that is in keep with its culture. By having competencies defined in the organization, it allows employees to know what they need to be productive. When properly defined, competencies, allows organizations to evaluate the extent to which behaviors employees are demonstrating and where they may be lacking. For competencies where employees are lacking, they can learn. This will allow organizations to know potentially what resources they may need to help the employee develop and learn those competencies. Competencies can distinguish and differentiate your organization from your competitors. While two organizations may be alike in financial results, the way in which the results were achieve could be different based on the competencies that fit their particular strategy and organizational culture. Lastly, competencies can provide a structured model that can be used to integrate management practices throughout the organization. Competencies that align their recruiting, performance management, training and development and reward practices to reinforce key behaviors that the organization values.

Dreyfus and Dreyfus on competency development

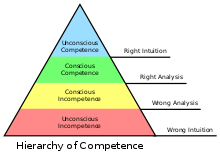

Dreyfus and Dreyfus[4] introduced nomenclature for the levels of competence in competency development. The causative reasoning of such a language of levels of competency may be seen in their paper on Calculative Rationality titled, "From Socrates to Expert Systems: The Limits and Dangers of Calculative Rationality".[5] The five levels proposed by Dreyfus and Dreyfus were:

- Novice: Rule-based behaviour, strongly limited and inflexible

- Experienced Beginner: Incorporates aspects of the situation

- Practitioner: Acting consciously from long-term goals and plans

- Knowledgeable practitioner: Sees the situation as a whole and acts from personal conviction

- Expert: Has an intuitive understanding of the situation and zooms in on the central aspects

The process of competency development is a lifelong series of doing and reflecting. As competencies apply to careers as well as jobs, lifelong competency development is linked with personal development as a management concept. And it requires a special environment, where the rules are necessary in order to introduce novices, but people at a more advanced level of competency will systematically break the rules if the situations requires it. This environment is synonymously described using terms such as learning organization, knowledge creation, self-organizing and empowerment.

Within a specific organization or professional community, professional competency is frequently valued. They are usually the same competencies that must be demonstrated in a job interview. But today there is another way of looking at it: that there are general areas of occupational competency required to retain a post, or earn a promotion. For all organizations and communities there is a set of primary tasks that competent people have to contribute to all the time. For a university student, for example, the primary tasks could be:

- Handling theory

- Handling methods

- Handling the information of the assignment

The four general areas of competency are:

- Meaning Competency: The person assessed must be able to identify with the purpose of the organization or community and act from the preferred future in accordance with the values of the organization or community.

- Relation Competency: The ability to create and nurture connections to the stakeholders of the primary tasks must be shown.

- Learning Competency: The person assessed must be able to create and look for situations that make it possible to experiment with the set of solutions that make it possible to complete the primary tasks and reflect on the experience.

- Change Competency: The person assessed must be able to act in new ways when it will promote the purpose of the organization or community and make the preferred future come to life.

McClelland and occupational competency

The Occupational Competency movement was initiated by David McClelland in the 1960s with a view to moving away from traditional attempts to describe competency in terms of knowledge, skills and attitudes and to focus instead on the specific self-image, values, traits, and motive dispositions (i.e. relatively enduring characteristics of people) that are found to consistently distinguish outstanding from typical performance in a given job or role. Different competencies predict outstanding performance in different roles, and that there is a limited number of competencies that predict outstanding performance in any given job or role. Thus, a trait that is a "competency" for one job might not predict outstanding performance in a different role. There is hence research on competencies needed in specific jobs or contexts.

Nevertheless, there have been developments in research relating to the nature, development, and assessment of high-level competencies in homes, schools, and workplaces.[6]

Perez-Capdevila and labor competencies

The most recent definition has been formalized by Javier Perez-Capdevila in 2017, who has written that the competences are fusions obtained from the complete mixture of the fuzzy sets of aptitudes and attitudes possessed by employees, both in a general and singular way. In these fusions, the degree of belonging to the resulting group expresses the extent to which these competencies are possessed.

Benefits of competencies

Competency models can help organizations align their initiatives to their overall business strategy. By aligning competencies to business strategies, organizations can better recruit and select employees for their organizations. Competencies have been become a precise way for employers to distinguish superior from average or below average performance. The reason for this is because competencies extend beyond measuring baseline characteristics and or skills used to define and assess job performance. In addition to recruitment and selection, a well sound Competency Model will help with performance management, succession planning and career development.

Career paths: Development of stepping stones necessary for promotion and long term career-growth

- Clarifies the skills, knowledge, and characteristics required for the job or role in question and for the follow-on jobs

- Identifies necessary levels of proficiency for follow-on jobs

- Allows for the identification of clear, valid, legally defensible and achievable benchmarks for employees to progress upward

- Takes the guesswork out of career progression discussions

Identifying skill gaps: Knowing whether employees are capable of performing their role in achieving corporate strategy

- Enables people to perform competency assessments in order to identify skill gaps at an individual and aggregate level

- When self-assessments are included, drives intrinsic motivation for individuals to close their own gaps

- Identifies re-skilling and upskilling opportunities for individuals, or consideration of other job roles

- Ensures organizations can rapidly act, support their people, and remain competitive

Performance management: Provides regular measurement of targeted behaviors and performance outcomes linked to job competency profile critical factors.

- Provides a shared understanding of what will be monitored, measured, and rewarded

- Focuses and facilitates the performance appraisal discussion appropriately on performance and development

- Provides focus for gaining information about a person's behavior on the job

- Facilitates effectiveness goal-setting around required development efforts and performance outcomes

Selection: The use of behavioral interviewing and testing where appropriate, to screen job candidates based on whether they possess the key necessary job competency profile:

- Provides a complete picture of the job requirements

- Increases the likelihood of selecting and interviewing only individuals who are likely to succeed on the job

- Minimizes the investment (both time and money) in people who may not meet the company's expectations

- Enables a more systematic and valid interview and selection process

- Helps distinguish between competencies that are trainable after hiring and those are more difficult to develop

Succession planning: Careful, methodical preparation focused on retaining and growing the competency portfolios critical for the organization to survive and prosper

- Provides a method to assess candidates’ readiness for the role

- Focuses training and development plans to address missing competencies or gaps in competency proficiency levels

- Allows an organization to measures its “bench strength”—the number of high-potential performers and what they need to acquire to step up to the next level

- Provides a competency framework for the transfer of critical knowledge, skills, and experience prior to succession – and for preparing candidates for this transfer via training, coaching and mentoring

- Informs curriculum development for leadership development programs, a necessary component for management succession planning

Training and development: Development of individual learning plans for individual or groups of employees based on the measurable “gaps” between job competencies or competency proficiency levels required for their jobs and the competency portfolio processed by the incumbent.

- Focuses training and development plans to address missing competencies or raise level of proficiency

- Enables people to focus on the skills, knowledge and characteristics that have the most impact on job effectiveness

- Ensures that training and development opportunities are aligned with organizational needs

- Makes the most effective use of training and development time and dollars

- Provides a competency framework for ongoing coaching and feedback, both development and remedial

Types of competencies

Behavioral competencies: Individual performance competencies are more specific than organizational competencies and capabilities. As such, it is important that they be defined in a measurable behavioral context in order to validate applicability and the degree of expertise (e.g. development of talent)

Core competencies: Capabilities and/or technical expertise unique to an organization, i.e. core competencies differentiate an organization from its competition (e.g. the technologies, methodologies, strategies or processes of the organization that create competitive advantage in the marketplace). An organizational core competency is an organization's strategic strength.

Functional competencies: Functional competencies are job-specific competencies that drive proven high-performance, quality results for a given position. They are often technical or operational in nature (e.g., "backing up a database" is a functional competency).[7]

Management competencies: Management competencies identify the specific attributes and capabilities that illustrate an individual's management potential. Unlike leadership characteristics, management characteristics can be learned and developed with the proper training and resources. Competencies in this category should demonstrate pertinent behaviors for management to be effective.

Organizational competencies: The mission, vision, values, culture and core competencies of the organization that sets the tone and/or context in which the work of the organization is carried out (e.g. customer-driven, risk taking and cutting edge). How we treat the patient is part of the patient's treatment.

Technical competencies: Depending on the position, both technical and performance capabilities should be weighed carefully as employment decisions are made. For example, organizations that tend to hire or promote solely on the basis of technical skills, i.e. to the exclusion of other competencies, may experience an increase in performance-related issues (e.g. systems software designs versus relationship management skills)

Examples:

Attention to detail

Is alert in a high-risk environment; follows detailed procedures and ensures accuracy in documentation and data; carefully monitors gauges, instruments or processes; concentrates on routine work details; organizes and maintains a system of records.

Commitment to safety

Understands, encourages and carries out the principles of integrated safety management; complies with or oversees the compliance with Laboratory safety policies and procedures; completes all required ES&H training; takes personal responsibility for safety.[8]

Communication

Writes and speaks effectively, using conventions proper to the situation; states own opinions clearly and concisely; demonstrates openness and honesty; listens well during meetings and feedback sessions; explains reasoning behind own opinions; asks others for their opinions and feedback; asks questions to ensure understanding; exercises a professional approach with others using all appropriate tools of communication; uses consideration and tact when offering opinions.

Cooperation/teamwork

Works harmoniously with others to get a job done; responds positively to instructions and procedures; able to work well with staff, co-workers, peers and managers; shares critical information with everyone involved in a project; works effectively on projects that cross functional lines; helps to set a tone of cooperation within the work group and across groups; coordinates own work with others; seeks opinions; values working relationships; when appropriate facilitates discussion before decision-making process is complete.

Customer service

Listens and responds effectively to customer questions; resolves customer problems to the customer's satisfaction; respects all internal and external customers; uses a team approach when dealing with customers; follows up to evaluate customer satisfaction; measures customer satisfaction effectively; commits to exceeding customer expectations.

Flexibility

Remains open-minded and changes opinions on the basis of new information; performs a wide variety of tasks and changes focus quickly as demands change; manages transitions from task to task effectively; adapts to varying customer needs.

Job knowledge/technical knowledge

Demonstrates knowledge of techniques, skills, equipment, procedures and materials. Applies knowledge to identify issues and internal problems; works to develop additional technical knowledge and skills.

Initiative and creativity

Plans work and carries out tasks without detailed instructions; makes constructive suggestions; prepares for problems or opportunities in advance; undertakes additional responsibilities; responds to situations as they arise with minimal supervision; creates novel solutions to problems; evaluates new technology as potential solutions to existing problems.

Innovation

Able to challenge conventional practices; adapts established methods for new uses; pursues ongoing system improvement; creates novel solutions to problems; evaluates new technology as potential solutions to existing problems.

Judgement

Makes sound decisions; bases decisions on fact rather than emotion; analyzes problems skillfully; uses logic to reach solutions.

Leadership:

Able to become a role model for the team and lead from the front. Reliable and have the capacity to motivate subordinates. Solves problems and takes important decisions.

Organization

Able to manage multiple projects; able to determine project urgency in a practical way; uses goals to guide actions; creates detailed action plans; organizes and schedules people and tasks effectively.

Problem solving

Anticipates problems; sees how a problem and its solution will affect other units; gathers information before making decisions; weighs alternatives against objectives and arrives at reasonable decisions; adapts well to changing priorities, deadlines and directions; works to eliminate all processes which do not add value; is willing to take action, even under pressure, criticism or tight deadlines; takes informed risks; recognizes and accurately evaluates the signs of a problem; analyzes current procedures for possible improvements; notifies supervisor of problems in a timely manner.

Quality control

Establishes high standards and measures; is able to maintain high standards despite pressing deadlines; does work right the first time and inspects work for flaws; tests new methods thoroughly; considers excellence a fundamental priority.

Quality of Work

Maintains high standards despite pressing deadlines; does work right the first time; corrects own errors; regularly produces accurate, thorough, professional work.

Quantity of work

Produces an appropriate quantity of work; does not get bogged down in unnecessary detail; able to manage multiple projects; able to determine project urgency in a meaningful and practical way; organizes and schedules people and tasks.

Reliability

Personally responsible; completes work in a timely, consistent manner; works hours necessary to complete assigned work; is regularly present and punctual; arrives prepared for work; is committed to doing the best job possible; keeps commitments.

Responsiveness to requests for service

Responds to requests for service in a timely and thorough manner; does what is necessary to ensure customer satisfaction; prioritizes customer needs; follows up to evaluate customer satisfaction.

Staff development

Works to improve the performance of oneself and others by pursuing opportunities for continuous learning/feedback; constructively helps and coaches others in their professional development; exhibits a “can-do” approach and inspires associates to excel; develops a team spirit.

Support of diversity

Treats all people with respect; values diverse perspectives; participates in diversity training opportunities; provides a supportive work environment for the multicultural workforce; applies the Lab's philosophy of equal employment opportunity; shows sensitivity to individual differences; treats others fairly without regard to race, sex, color, religion, or sexual orientation; recognizes differences as opportunities to learn and gain by working together; values and encourages unique skills and talents; seeks and considers diverse perspectives and ideas.

Building a competency model

Many Human Resource professionals are employing a competitive competency model to strengthen nearly every facet of talent management—from recruiting and performance management, to training and development, to succession planning and more. A job competency model is a comprehensive, behaviorally based job description that both potential and current employees and their managers can use to measure and manage performance and establish development plans. Often there is an accompanying visual representative competency profile as well (see, job profile template).

Creating a competency framework is critical for both employee and system success. An organization cannot produce and develop superior performers without first identifying what superior performance is. In the traditional method, organizations develop behavioral interview questions, interview the best and worst performers, review the interview data (tracking and coding how frequently keywords and descriptions were repeated, selecting the SKAs that demonstrated best performance and named the competencies)

One of the most common pitfalls that organizations stumble upon is that when creating a competency model they focus too much on job descriptions instead the behaviors of an employee. Experts say that the steps required to create a competency model include:

- Gathering information about job roles.

- Interviewing subject matter experts to discover current critical competencies and how they envision their roles changing in the future.

- Identifying high-performer behaviors.

- Creating, reviewing (or vetting) and delivering the competency model.

Once the competency model has been created, the final step involves communicating how the organization plans to use the competency model to support initiatives such as recruiting, performance management, career development, succession planning as well as other HR business processes.

The problem with the traditional method is the time that it takes to build.

Agile Method for building a competency model

Because skills are changing so rapidly, by the time the traditional method is completed, the competency model may already be out of date.

For this reason, an agile method, designed to model top performers in a particular role, may be used. It includes these steps:

- Select 4-6 high performing job incumbents, whose behavior you wish to model, to participate in a workshop

- Conduct a one-day rapid job analysis workshop to capture the categories of things they do, what they do, and how they do it, including what separates good from great

- Draft the details of the competency model based on the workshop and provide it to the workshop participants for review and editing

- Consolidate draft feedback and conduct a live workshop with participants to come to consensus about changes

- Identify the target level of proficiency for each task in the model based on the final behaviors

- Optionally vet the completed model with a larger group of high performing job incumbents

- Begin making the competency model actionable, and plan a formal review with other high performing job incumbents at least annually to ensure currency

This method typically takes 3 weeks.

Arzesh Competency Model

This method introduces different steps of model implementation o as follows[9]:

1- Identification of competencies

2- Ranking competencies

3- Creation of databases

4- Creation of the final model

For Creation of Final Model, It describes these Steps:

1- Defining competency

2- Identifying the main competencies

- Identifying the main competency criteria

3- Establishing competencies database

4- Establishing managers’ database

5- Establishing Competency Ranking database

- Selecting suitable method of quantification

- Determining the weight of each criterion and prioritization of the competency criteria

6- Establishing Managers’ Ranking database

- Assess the Competency of Managers by experienced managers qualified with expedience and allocation α ijk

- Concise evaluation by Assessment and Allocation Centers β ijk

- Calculation of the competency number of each manager for each competency criterion and calculation of the average competency of each manager (a)

Modeling in the project competencies section follows these steps:

The model plan for the second part is as follows:

1- Determining the status of the organization

2- Establishing a database of organization’s projects

3- Find the Determine the complexity number range

4- Choosing the manager with the same score as the obtained number for each project and assign it to the project

Outsourcing competency models

The most frequently mentioned “cons” mentioned by competency modeling experts regarding creating a competency model is time and expense. This is also a potential reason why some organizations either don't have a competency model in place or don't have a complete and comprehensive competency model in place. Building a competency model requires careful study of the job, group, and organization of industry. The process often involves researching performance and success, interviewing high performing incumbents, conducting focus groups and surveys.

When asked in a recent webcast hosted by the Society of Human Resource Management (SHRM), 67 percent of webcast attendees indicated that hastily written job descriptions may be the root cause of incomplete competencies. Defining and compiling competencies is a long process that may sometimes require more effort and time than most organizations are willing to allocate. Instead of creating a competency model themselves, organizations are enlisting the help of specialist/consultants to assess their organization and create a unique competency model specific to their organization. There are many ways that organizations can outsource these functions. When asked in a recent webcast hosted by the Society of Human Resource Management (SHRM), 67 percent of webcast attendees indicated that hastily written job descriptions may be the root cause of incomplete competencies. Defining and compiling competencies is a long process that may sometimes require more effort and time than most organizations are willing to allocate. Instead of creating a competency model themselves, organizations are enlisting the help of specialist/consultants to assess their organization and create a unique competency model specific to their organization. There are many ways that organizations can outsource these functions. however, many competency models which have been created, are usable in many companies.the most importance of these are introduced:

1-Project Manager Competence Development Framework (PMCDF) PMCDF framework, studied since 1997, is the first standard of the Project Management Institute (PMI) addressing the issue of "improving performance of project staff". This standard is an important step in continuing the mission of this association for definition of the body of knowledge supporting project management profession and provision of standards for its application. PMCDF framework aims to help project managers and those interested in project management to manage their profession development.

2-Project Manager Competency Framework (ICB) The International Project Management Institute has divided the project management competencies into three categories: technical, behavioral and structural-environment. According to this standard, we need 46 elements to describe the competency of the project manager (a professional specialist who plans and controls the project).

3-National Competency Standards for Project Management (NCSPM) The AIPM (Austrian Institute for project management) was formed in 1976 as the project manager's forum and has been instrumental in progressing the profession of project management in Australia. The AIPM developed and documented their standard as the Australian national competency standards for project management.

4-The Model for selection of competent manager in constructional projects This model is designed based on the special conditions of constructional projects. In this model, first, the characteristics of a competent manager based on studies conducted on various standards and models of the world, and after studies on competency in the scientific and traditional attitudes, are divided into several categories and, finally, after identification of the criteria and measurable criteria and sub-criteria, with the help of the network analysis process, each of the criteria and sub-criteria is weighed in two different companies, and finally ranked among the identified factors and based on the weighted average of each of the sub-criteria, for selection of a competent manager among several volunteer managers, modeling is performed. The following figure shows the criteria and sub-criteria required for selection of the competent manager.[11]

5-South African National Competency Model (SABPP) On October 16, 2012, a major human resources organization which was called SABPP created a National Competency Model for South Africa. SABPP is not only a professional organization in the field of Human resource researches but also active in the field of training logistics. This company has developed training programs in the field of management and industrial psychology. Therefore, in development of this model, the views of industrial psychologists have been used. Dr. Lydia Silichemith has headed the research group. According to his early studies, creation of SABPP's competency model is important because it describes the requirements for any professional in a variety of occupational contexts.

6-The Arzesh Competency Model Based on this model, a suitability model should follow the following objectives: 1- Merit 2. Educate future managers. The purpose of this model is to deserve and develop the culture of success in organizations. The value model tries to identify and develop, within several stages, the competencies of its forces: First step - Identify the capabilities of the organization's human resources Stage II - Identification of job competencies Third stage - Human Resource Ranking Step Four - Meritocracy: Use people in posts that are commensurate with their competencies.[12]

Competency libraries

Organizations that don't have the time or resources to build to develop competencies can purchase comprehensive competency libraries online. These universal competencies are applicable to all organizations across functions. Organizations can then take these competencies and begin building a competency model.

Specialists/consultants

For organizations that find they want a specialist to help create a competency model, outsourcing the entire process is also possible. Through outsourcing, a specialist/consultant can work with your company to pinpoint the root causes of your workforce challenges. By identifying these workforce challenges, customized action plans can then be created to meet the specific needs. Typically, these solutions are unique to every organization's culture and challenges.

Competency identification

Competencies required for a post are identified through job analysis or task analysis, using techniques such as the critical incident technique, work diaries, and work sampling.[13] A future focus is recommended for strategic reasons.[14]

See also

- Circle of competence – The subject area which matches a person's skills or expertise

- Competency architecture

- Competency dictionary – A tool or data structure that includes all or most of the general competencies needed to cover all job families and competencies that are core or common to all jobs within an organization

- Competency-based management – Link between human resources management and the overall strategic plan of an organization

- Dunning–Kruger effect – Cognitive bias in which incompetent people assess themselves as competent, the tendency for incompetent people to grossly overestimate their skills

- Outline of business management – Overview of and topical guide to business management

- Personal development

- Performance appraisal

- Performance improvement

- Peter principle – Concept that people in a hierarchy are promoted until no longer competent, the tendency for competent workers to be promoted just beyond the level of their competence

- Professional development – Learning to earn or maintain professional credentials

- Seagull manager, management style

References

- Maaleki, Ali (9 April 2018). The ARZESH Competency Model : Appraisal & Development Manager's Competency Model. Lambert Academic Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 9786138389668.

- Thirteenth Australasian Computing Education Conference (ACE 2011), Perth, Australia, 2011. Hamer, John (ed), De Raadt, Michael (ed), Barnes, D. J., Berry, G., Buckland, R., Cajander, A. [Sydney]. ISBN 9781920682941. OCLC 927045654.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Collin, Audrey (1989). Managers' Competence: Rhetoric, Reality and Research. Personnel Review (Report). 18. pp. 20–25. doi:10.1108/00483488910133459.

- Dreyfus, Stuart E.; Dreyfus, Hubert L. (February 1980). "A Five-Stage Model of the Mental Activities Involved in Directed Skill Acquisition" (PDF). Washington, DC: Storming Media. Retrieved June 13, 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Professor Hubert Dreyfus". berkeley.edu.

- Raven, J., & Stephenson, J. (Eds.). (2001). Competency in the Learning Society. New York: Peter Lang.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-04-03. Retrieved 2015-05-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Safety, Competency and Commitment: Competency Guidelines for Safety-Related System Practitioners https://www.amazon.com/dp/085296787X

- maaleki, Ali (2019). The arzesh competency model. germany: lambert Academy Publishing. pp. 144–145. ISBN 9786138389668.

- Maaleki, Ali (2019). The Arzesh Competency Model. germany: Lambert Academy Publishing. p. 254. ISBN 9786138389668.

- maaleki, ali. "Project manager competency Model based on ANP" (PDF). IEOM Society. IEOM.

- Maaleki, Ali (9 April 2018). The ARZESH Competency Model : Appraisal & Development Manager's Competency Model (1 ed.). Lambert Academic Publishing. p. 74. ISBN 9786138389668.

- Robinson, M. A. (2010). "Work sampling: Methodological advances and new applications". Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing & Service Industries. 20 (1): 42–60. doi:10.1002/hfm.20186.

- Robinson, M. A.; Sparrow, P. R.; Clegg, C.; Birdi, K. (2007). "Forecasting future competency requirements: A three-phase methodology". Personnel Review. 36 (1): 65–90. doi:10.1108/00483480710716722.

Further reading

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Competence |

- Eraut, M. (1994). Developing Professional Knowledge and Competence. London: Routledge.

- Gilbert, T.F. (1978). Human Competence. Engineering Worthy Performance. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Mulder, M (2001). "Competence Development – Some Background Thoughts". The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension. 7 (4): 147–159. doi:10.1080/13892240108438822.

- Shippmann, J. S.; Ash, R. A.; Battista, M.; Carr, L.; Eyde, L. D.; Hesketh, B.; Kehoe, J.; Pearlman, K.; Sanchez, J. I. (2000). "The practice of competency modeling". Personnel Psychology. 53 (3): 703–740. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2000.tb00220.x.

- White, R. W. (1959). "Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence". Psychological Review. 66 (5): 297–333. doi:10.1037/h0040934. PMID 13844397.