Wetsuit

A wetsuit is a garment worn to provide thermal protection while wet. It is usually made of foamed neoprene, and is worn by surfers, divers, windsurfers, canoeists, and others engaged in water sports and other activities in or on water, primarily providing thermal insulation, but also buoyancy and protection from abrasion, ultraviolet exposure and stings from marine organisms. The insulation properties of neoprene foam depend mainly on bubbles of gas enclosed within the material, which reduce its ability to conduct heat. The bubbles also give the wetsuit a low density, providing buoyancy in water.

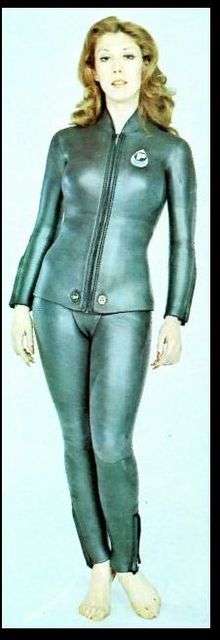

Spring suit (shorty) and steamer (full suit) one-piece suits | |

| Uses | Thermal protection for water-sport and underwater work |

|---|---|

| Related items | Diving suit, dry suit, hot water suit, rash guard |

Hugh Bradner, a University of California, Berkeley, physicist invented the modern wetsuit in 1952. Wetsuits became available in the mid-1950s and evolved as the relatively fragile foamed neoprene was first backed, and later sandwiched, with thin sheets of tougher material such as nylon or later spandex (also known as lycra). Improvements in the way joints in the wetsuit were made by gluing, taping and blindstitching, helped the suit to remain waterproof and reduce flushing, the replacement of water trapped between suit and body by cold water from the outside.[1] Further improvements in the seals at the neck, wrists, ankles and zippers produced a suit known as a "semi-dry".

Different types of wetsuit are made for different uses and for different temperatures.[2] Suits range from a thin (2 mm or less) "shortie", covering just the torso, to a full 8 mm semi-dry, usually complemented by neoprene boots, gloves and hood.

The difference between a wetsuit and a dry suit is that a wetsuit allows water to enter the suit, while dry suits are designed to prevent water from entering, thus keeping the undergarments dry and preserving their insulating effectiveness. Wetsuits can give adequate protection in warm to moderately cold waters. Dry suits are typically more expensive and more complex to use, but can be used where protection from lower temperatures or contaminated water is needed.[3]

Uses

Wetsuits are used for thermal insulation for activities where the user is likely to be immersed in water, or frequently doused with heavy spray, often approaching from near-horizontal directions, where normal wet-weather clothing is unlikely to keep the water out. Activities include underwater diving, sailing, sea rescue operations, surfing, river rafting, whitewater kayaking and in some circumstances, endurance swimming.

- Scuba divers in steamer wetsuits, one wearing a hood

One-piece suit worn by kitesurfer

One-piece suit worn by kitesurfer- High visibility suit for sea rescue

Surfers in steamer wetsuits

Surfers in steamer wetsuits

In open water swimming events the use of wetsuits is controversial, as some participants claim that wetsuits are being worn for competitive advantage and not just for warmth.[4]

Unlike triathlons, which allow swimmers to wear wetsuits when the water is below a certain temperature (the standard is 78 °F (26 °C) at the surface or up to 84 °F (29 °C) for unofficial events.[5]), most open water swim races either do not permit the use of wetsuits,[6] (usually defined as anything covering the body above the waist or below the knees), or put wetsuit-clad swimmers in a separate category and/or make them ineligible for race awards. This varies by locales and times of the year, where water temperatures are substantially below comfortable.

Insulation

Still water (without currents or convection) conducts heat away from the body by pure thermal diffusion, approximately 20 to 25 times more efficiently than still air.[2][7] Water has a thermal conductivity of 0.58 Wm−1K−1 while still air has a thermal conductivity of 0.024 Wm−1K−1,[8] so an unprotected person can succumb to hypothermia even in warmish water on a warm day.[9] Wetsuits are made of closed-cell foam neoprene, a synthetic rubber that contains small bubbles of nitrogen gas when made for use as wetsuit material (neoprene may also be manufactured without foaming for many other applications where insulating qualities are not important). Nitrogen, like most gases, has very low thermal conductivity compared to water or to solids,[note 1] and the small and enclosed nature of the gas bubbles minimizes heat transport through the gas by convection in the same way that cloth fabrics or feathers insulate by reducing convection of enclosed air spaces. The result is that the gas filled cavities restrict heat transfer to mostly conduction, which is partly through bubbles of entrapped gas, thereby greatly reducing heat transfer from the body (or from the layer of warmed water trapped between the body and the wetsuit) to the colder water surrounding the wetsuit.

Uncompressed foam neoprene has a typical thermal conductivity in the region of 0.054 Wm−1K−1, which produces about twice the heat loss of still air, or one-tenth the loss of water. However at a depth of about 15 metres (50 ft) of water, the thickness of the neoprene will be halved and its conductivity will be increased by about 50%, allowing heat to be lost at three times the rate at the surface.[10]

A wetsuit must have a snug fit to work efficiently when immersed; too loose a fit, particularly at the openings (wrists, ankles, neck and overlaps) will allow cold water from the outside to enter when the wearer moves.[1] Flexible seals at the suit cuffs aid in preventing heat loss in this fashion. The elasticity of the foamed neoprene and surface textiles allow enough stretch for many people to effectively wear off-the-shelf sizes, but others have to have their suits custom fitted to get a good fit that is not too tight for comfort and safety.

Foamed neoprene is very buoyant, helping swimmers to stay afloat, and for this reason divers need to carry extra weight based on the volume of their suit to achieve neutral buoyancy near the surface.[2] However, the suit loses thermal protection as the bubbles in the neoprene are compressed at depth[11][note 2] Buoyancy is also reduced by compression, and scuba divers can correct this by inflating the buoyancy compensator.

Semi-dry suits

Semi-dry suits are effectively a wetsuit with improved seals at wrist, neck and ankles and also usually featuring a waterproof dry-zip. Together, these features greatly reduce the amount of water moving through the suit as the wearer moves in the water. The wearer gets wet in a semi-dry suit but the water that enters is soon warmed up and is not "flushed" out by colder water entering from the outside environment, so the wearer remains warm. The trapped layer of water does not add significantly to the suit's insulating ability. Any residual water circulation past the seals still causes heat loss, but this loss is minimised due the more effective seals. Though more expensive and more difficult to take on and off than a wetsuit (in most cases, a helper will be needed to close the dry-zip, which is usually located across the shoulders), semi-dry suits are cheap and simple compared to dry suits, and in the case of scuba diving, require no additional skills to use. They are usually made from thick Neoprene (typically 6mm or more), which provides good thermal protection at shallow depth, but lose buoyancy and thermal protection as the gas bubbles in the Neoprene compress at depth, like a normal wetsuit. Early suits marketed as "Semi-dry" suits came come in various configurations including a one-piece full-body suit or two pieces, made of 'long johns' and a separate 'jacket'. Almost all modern semi-dry suits are one piece suits with, with the zipper usually being a dry-zip across the shoulders on the back, but other arrangements have been used. Semi-dry suits do not usually incorporate boots, and modern designs usually do not incorporate the hood (as creating a secure seal around the face is difficult) so a separate pair of wetsuit boots, hood and gloves as worn, as needed. They are most suitable for use where the water temperature is between 10 and 20 °C (50 and 68 °F).

Heated suits

Electrically heated wetsuits are also available on the market. These suits have special heating panels integrated in the back of the wetsuit. The power for heating comes from batteries also integrated into the wetsuit.[12] Even more versatile is the heated neoprene vest that functions the same as the heated wetsuit but can be worn under any type of wetsuit.

Wetsuits heated by a flow of hot water piped from the surface are standard equipment for commercial diving in cold water, particularly where the heat loss from the diver is increased by use of helium based breathing gases.[13] Hot water suits are a loose fit as there is a constant supply of heated water piped into the suit which must escape to allow even flow distribution. Flushing with cold water is prevented by the constant outflow of heating water.

History

Origins

In 1952, UC Berkeley and subsequent UC San Diego SIO physicist Hugh Bradner, who is considered to be the original inventor[14] and "father of the modern wetsuit,"[14] had the insight that a thin layer of trapped water could be tolerated between the suit fabric and the skin, so long as insulation was present in the fabric in the form of trapped bubbles. In this case, the water would quickly reach skin temperature and the air in the fabric would continue to act as the thermal insulation to keep it that way. In the popular mind, the layer of water between skin and suit has been credited with providing the insulation, but Bradner clearly understood that the suit did not need to be wet because it was not the water that provided the insulation but rather the gas in the suit fabric.[14][15] He initially sent his ideas to Lauriston C. "Larry" Marshall who was involved in a U.S. Navy/National Research Council Panel on Underwater Swimmers.[16] However, it was Willard Bascom, an engineer at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California, who suggested neoprene as a feasible material to Bradner.[15]

Bradner and Bascom were not overly interested in profiting from their design and were unable to successfully market a version to the public.[15] They attempted to patent their neoprene wetsuit design, but their application was rejected because the design was viewed as too similar to a flight suit.[15] The United States Navy also turned down Bradner's and Bascom's offer to supply its swimmers and frogmen with the new wetsuits due to concerns that the gas in the neoprene component of the suits might make it easier for naval divers to be detected by underwater sonar.[15] The first written documentation of Bradner's invention was in a letter to Marshall, dated June 21, 1951.[16]

Jack O'Neill started using closed-cell neoprene foam which was shown to him by his bodysurfing friend, Harry Hind, who knew of it as an insulating material in his laboratory work. After experimenting with the material and finding it superior to other insulating foams, O'Neill founded the successful wetsuit manufacturing company called O'Neill in a San Francisco garage in 1952, later relocating to Santa Cruz, California[17] in 1959 with the motto "It's Always Summer on the Inside".[18][19] Bob and Bill Meistrell, from Manhattan Beach, California, also started experimenting with neoprene around 1953. They started a company which would later be named Body Glove.

Neoprene was not the only material used in early wetsuits, particularly in Europe. The Pêche-Sport "isothermic" suit[20][21][22] invented by Georges Beuchat in 1953 and the UK-made Siebe Gorman Swimsuit[23] were both made out of sponge rubber. The Heinke Dolphin Suit[24] of the same period, also made in England, came in a green male and a white female version, both manufactured from natural rubber lined with stockinet.

Development of suit design

Originally, wetsuits were made only with sheets of foam-rubber or neoprene that did not have any backing material. This type of suit required care while pulling it on because the foam-rubber by itself is both fragile and sticky against bare skin. Stretching and pulling excessively easily caused these suits to be torn open. This was somewhat remedied by thoroughly powdering the suit and the diver's body with talc to help the rubber slide on more easily.

Backing materials first arrived in the form of nylon cloth applied to one side of the neoprene. This allowed a swimmer to pull on the suit relatively easily since the nylon took most of the stress of pulling on the suit, but the suit still had the bare foam exposed on the outside and the nylon was relatively stiff, limiting flexibility. A small strip reversed with the rubber against the skin could help provide a sealing surface to keep water out around the neck, wrists, and ankles.

In the early 1960s, the British Dunlop Sports Company brought out its yellow Aquafort neoprene wetsuit, whose high visibility was designed to improve diver safety. However, the line was discontinued after a short while and wetsuits reverted to their black uniformity. The colorful wetsuits seen today first arrived in the 1970s when double-backed neoprene was developed. In this material the foam-rubber is sandwiched between two protective fabric outer layers, greatly increasing the tear-resistance. An external layer also meant that decorative colors, logos, and patterns could be made with panels and strips sewn into various shapes. This change from bare flat black rubber to full color took off in the 1980s with brilliant fluorescent colors common on many suits.

Improvements in suit assembly

The first suits used traditional sewing methods to simply overlap two strips of rubber and sew them together. In a rubber wetsuit this does not work well for a number of reasons, the main one being that punching holes straight through both layers of foam for the thread opens up passages for water to flow in and out of the suit. The second problem is that the stretching of the foam tended to enlarge the needle holes when the suit was worn. This meant that a wetsuit could be very cold all along the seams of the suit. And although the sewn edge did hold the two pieces together, it could also act as a perforated tear edge, making the suit easier to tear along the seams when putting it on and taking it off.

When nylon-backed neoprene appeared, the problem of the needle weakening the foam was solved, but still the needle holes leaked water along the seams.

Seam taping

To deal with all these early sewing problems, taping of seams was developed. The tape is a strong nylon cloth with a very thin but solid waterproof rubber backing. The tape is applied across the seam and bonded either with a chemical solvent or with a hot rolling heat-sealer to melt the tape into the neoprene.

With this technology, the suit could be sewn and then taped, and the tape would cover the sewing holes as well as providing some extra strength to prevent tearing along the needle holes.

When colorful double-backed designer suits started appearing, taping moved primarily to the inside of the suit because the tape was usually very wide, jagged, black, and ugly, and was hidden within the suit and out of sight.

Many 1960s and 1970s wetsuits were black with visible yellow seam taping. The yellow made the divers more easily seen in dark low-visibility water. To avoid this problem O'Neill fabricators developed a seam-tape which combined a thin nylon layer with a polyester hemming tape. Applied over the interior of the glued & sewn seam, then anneal bonded with a hand held teflon heating iron produced a seam that was both securely sealed and much stronger.

Seam gluing

Another alternative to sewing was to glue the edges of the suit together. This created a smooth, flat surface that did not necessarily need taping, but unfortunately, raw foam glued to foam is not a strong bond and still prone to tearing.

Most early wetsuits were fabricated completely by hand, which could lead to sizing errors in the cutting of the foam sheeting. If the cut edges did not align correctly or the gluing was not done well, there might still be water leakage along the seam.

Initially, suits could be found as being sewn only, glued only, taped only, then also sewn and taped, or glued and taped, or perhaps all three.

Blindstitch revolution

Sometime after nylon-backed neoprene appeared, the blind stitch method was developed. A blindstitch sewing machine uses a curved needle, which does not go all the way through the neoprene but just shallowly dips in behind the fabric backing, crosses the glue line, and emerges from the surface on the same side of the neoprene.[1] This is similar to the overlock stitching used for teeshirts and other garments made from knitted fabrics.

The curved needle allows the fabric backing to be sewn together without punching a hole completely through the neoprene, and thereby eliminating the water-leakage holes along the seam. Blindstitch seams also lay flat, butting up the edge of one sheet against another, allowing the material to lay flatter and closer to the skin. For these reasons blindstitching rapidly became the primary method of sewing wetsuits together, with other methods now used mainly for decorative or stylistic purposes.

Further advances in suit design

Highly elastic fabrics such as spandex (also known as lycra) have mostly replaced plain nylon backing, since the nylon by itself cannot be stretched and makes the neoprene very stiff. Incorporating Lycra into the backing permits a large amount of stretching that does not damage the suit, and allowed suits to become closer fitting.

After the development of double-backed neoprene, singled-backed neoprene still had its uses for various specific purposes. For example, a thin strip of single-backed wrapped around the leg, neck, and wrist openings of the suit creates a seal that greatly reduces the flushing of water in and out of the suit as the person's body moves. But since the strip is very narrow, it does not drag on the skin of the wearer and thus makes the suit easy to put on and remove. The strip can also be fitted with the smooth side out and folded under to form a seal with a small length of smooth surface against the skin.

As wetsuit manufacturers continued to develop suit designs, they found ways that the materials could be further optimized and customized. The O'Neill Animal Skin created in 1974 by then Director of Marketing, E.J. Armstrong, was one of the first designs combining a turtle-neck based on the popular Sealsuit with a flexible lightweight YKK horizontal zipper across the back shoulders similar in concept to the inflatable watertight Supersuit (developed by Jack O'Neill in the late 1960s). The Animal Skin eventually evolved molded rubber patterns bonded onto the exterior of the neoprene sheeting ( a technique E.J. Armstrong perfected for application of the moulded raised rubber Supersuit logo to replace the standard flat decals ). This has been carried on as stylized reinforcing pads of rubber on the knees and elbows to protect the suit from wear, and allows logos to be directly bonded onto raw sheet rubber. Additionally, the Animal Skin's looser fit allowed for the use of a supplemental vest in extreme conditions.

In the early 1970s Gul Wetsuits pioneered the one-piece wetsuit named as the steamer. Its name was given because of the steam given off from the suit once taken off allowing heat and water held inside to escape. One-piece wetsuits are still sometimes referred to as 'Steamers'.[25]

In recent years, manufacturers have experimented by combining various materials with neoprene for additional warmth or flexibility of their suits. These include, but are not limited to, spandex, and wool.

Precision computer-controlled cutting and assembly methods, such as water-jet cutting, have allowed ever greater levels of seam precision, permitting designers to use many small individual strips of different colors while still keeping the suit free of bulging and ripples from improper cutting and sewing. Further innovations in CAD (Computer Aided Design) technology allow precision cutting for custom-fit wetsuits.

Return of single-backed neoprene

As wetsuits continued to evolve, their use was explored in other sports such as open-water swimming and triathlons. Although double-backed neoprene is strong, the cloth surface is relatively rough and creates a large amount of drag in the water, slowing down the swimmer. A single-backed suit has a smoother exterior surface which causes less drag.[1] With the advances of elastic Lycra backings and blindstitching, single-backed neoprene suits could be made that outperformed the early versions from the 1970s. Other developments in single-backed wetsuits include the suits designed for free-diving and spearfishing. Single lined neoprene is more flexible than double lined. To achieve flexibility and low bulk for a given warmth of suit, they are unlined inside, and the slightly porous raw surface of the neoprene adheres closely to the skin and reduces flushing of the suit. The lined outer surface may be printed with camouflage patterns for spearfishing and is more resistant to damage while in use.[26]

Some triathlon wetsuits go further, and use rubber-molding and texturing methods to roughen up the surface of the suit on the forearms, to increase forward drag and help pull the swimmer forwards through the water. Extremely thin 1 mm neoprene is also often used in the under-arm area, to decrease stretch resistance and reduce strain on the swimmer when they extend their arms out over their head.

Wetsuits used for caving are often single-backed with a textured surface known as "sharkskin" which is a thin layer where the neoprene is less expanded. This makes it more abrasion resistant for squeezing between rocks and doesn't get torn in the way that fabric does.

Another reason to eliminate the external textile backing is to reduce water retention which can increase evaporative cooling and wind chill in suits used mainly out of the water.[26]

Types

Different shapes of wetsuit are available, in order of coverage:

- A sleeveless vest, covering only the torso, provides minimal coverage. Some include an attached hood. These are not usually intended to be worn alone, but as an extra layer over or under a longer wetsuit.

- A hooded tunic, covering the torso and head, with short legs and either short or no sleeves, is generally intended to be worn over a full suit, and has a zip closure. It may be fitted with pockets for transporting accessories.

- A jacket covers the torso and arms, with little to no coverage for the legs. Some jackets have short legs like a shorty, others feature leg holes similar to a woman's swimsuit. A third style, the beavertail or bodysuit, has a flap which passes through the crotch and attaches at the front with clips, toggles or velcro fasteners. It is worn with (over) or without a long john or trousers. A jacket may include an integral hood, and may have a full or partial front zipper.

- A spring suit covers the torso and has short or long sleeves and short legs.

- Trousers cover the lower torso and legs.

- A short john, shorty covers the torso and legs to the knee only; does not have sleeves and is a short legged version of the long john.

- A long john, johnny, johnny suit, or farmer john/jane (depending on the gender the suit is designed for) covers the torso and legs only; it resembles a bib overall, hence the nickname.

- A full suit or steamer[27] covers the torso and the full length of the arms and legs. Some versions come with sleeves the length of a standard t-shirt and known as a short-sleeved steamer.

Some suits are arranged in two parts; the jacket and long johns can be worn separately in mild conditions or worn together to provide two layers of insulation around the torso in cold conditions. Typically, two-piece cold water wetsuits have 10 to 14 mm of material around the torso and 5 to 7 mm for the limbs.

Thickness

Wetsuits are available in different thicknesses depending on the conditions for which they are intended.[2] The thicker the suit, the warmer it will keep the wearer, but the more it will restrict movement. Because wetsuits offer significant protection from jellyfish, coral, sunburn and other hazards, many divers opt to wear a thin suit which provides minimal insulation (often called a "bodysuit") even when the water is warm enough to comfortably forego insulating garments.[2] A thick suit will restrict mobility, and as the thickness is increased the suit may become impractical, depending on the application. This is one reason why dry suits may be preferable for some applications. A wetsuit is normally specified in terms of its thickness and style. For instance, a wetsuit with a torso thickness of 5 mm and a limb thickness of 3 mm will be described as a "5/3". With new technologies the neoprene is getting more flexible. Modern 4/3 wetsuits, for instance, may feel as flexible as a 3/2 of only a few years ago. Some suits have extra layers added for key areas such as the lower back. Improved flexibility may come at the cost of greater compressibility, which reduces insulation at depth, but this is only important for diving.

Surface finish

Foam neoprene used for wetsuits is always closed cell, in that the gas bubbles are mostly not connected to each other inside the neoprene. This is necessary to prevent water absorption, and the gas bubbles do most of the insulation. Thick sheets of neoprene are foamed inside a mould, and the surfaces in contact with the mould take on the inverse texture of the mould surfaces. In the early days of wetsuits this was often a diamond pattern or similar, but can also be slick and smooth for low drag and quick drying. The cut surfaces of the foam have a slightly porous mat finish as the cutting process passes through a large number of bubbles, leaving what is called an open cell surface finish, but the bulk of the foam remains closed cell. The open cell finish is the most stretchy and the least tear resistant. It is relatively form fitting and comfortable on the skin, but the porosity encourages bacterial growth if not well washed after use, and the foam surface does not slide freely against skin.[26]

The cut surfaces are usually bonded to a nylon knit fabric, which provides much greater tear resistance, at the expense of some loss of flexibility. This fabric can be bonded to one or both surfaces in various combinations of weight and colour, and can be thin and relatively smooth and fragile, or thicker and stronger and less stretchy. Fabric lined on one side only is more flexible than double lined.[26]

A specialized kind of wetsuit, with a very smooth (and somewhat delicate) outer surface known as smoothskin, which is the original outer surface of the foamed neoprene block from which the sheets are cut, is used for long distance swimming, triathlon competitive apnoea and bluewater spearfishing. These are designed to maximize the mobility of the limbs while providing both warmth and buoyancy, but the surface is delicate and easily damaged. The slick surface also dries quickly and is least affected by wind chill when out of the water.[1][26]

Both smoothskin and fabric lined surfaces can be printed to produce colour patterns such as camouflage designs, which may give spearfishermen and combat divers an advantage.[26]

Closures

Zippers are often used for closure or for providing a close fit at the wrists and ankles, but they also provide leakage points for water. Jackets may have a full or partial front zipper, or none at all. Full body suits may have a vertical back zipper, a cross-shoulder zipper or a vertical front zipper. Each of these arrangements has some advantages and some disadvantages:

- The front zipper is easy to operate, but the suit may be difficult to remove from the shoulders without assistance, and the zip is uncomfortable for lying on a surfboard. It is relatively inflexible and placed over a part of the body where a lot of flexibility is desirable. The top of the closure will leak to some extent. The top end of the zip may be easily opened for comfort when the wearer is warm, but the zip may also press into the throat, which can be uncomfortable.

- Cross shoulder zipper can be made relatively watertight as it has no free ends, and is therefore used in semi-dry wetsuits. It is difficult to operate for the wearer and relatively highly stressed at the shoulders due to arm movement. The zip is also relatively vulnerable to damage from diving harnesses.

- Cross chest zipper has similar advantages to cross shoulder, but is easy to reach.

- Vertical back zippers are possibly the most common arrangement as they can be operated with a lanyard. They are relatively comfortable for most applications, the suit is easy to remove, and they place the zipper directly over the spine, which though flexible in bending, does not change much in length. The top of the closure will leak to some extent.

Sizing and fit

Wetsuits that fit too tightly can cause difficulty breathing or even acute cardiac failure,[2] and a loose fit allows considerable flushing which reduces effectiveness of insulation, so a proper fit is important. The quality of fit is most important for diving as this is where the thickest suits are used and the heat loss is potentially greatest. A diving wetsuit should touch the skin over as much of the body that it covers as comfortably possible, both when the wearer is relaxed and when exercising. This is difficult to achieve and the details of style and cut can affect the quality of fit. Gaps where the suit does not touch the skin will vary in volume as the diver moves and this is a major cause of flushing.

Wetsuits are made in several standard adult sizes and for children. Custom fitted suits are produced by many manufacturers to provide a better fit for people for whom a well fitting off-the shelf suit is not available.

Accessories

Usually a wetsuit has no covering for the feet, hands or head, and the diver must wear separate neoprene boots, gloves and hood for additional insulation and environmental protection. Other accessories to the basic suit include pockets for holding small items and equipment, and knee-pads, to protect the knee area from abrasion and tearing, usually used by working divers. Suits may have abrasion protection pads in other areas depending on the application.

Hoods

Using hoods: in the thermal balance of the human body, the heat loss over the head is at least 20% of the whole balance. Thus, for the sake of thermal protection of the diver, wearing a well-fitting hood is useful, even at fairly moderate water temperatures. Hoods have been reported to cause claustrophobia[2] in a minority of users, sometimes due to poor fit. The hood should not fit too tightly round the neck. Flushing in the neck area can be reduced by using a hood attached to the top part of the suit, or by having sufficient overlap between the hood and the top part of the suit to constrain flow between the two parts. This can be achieved by tucking a circular flap at the base of the neck of the hood under the top of the suit before closing the zip, or by having a high neck on the suit.

Boots

Wetsuit boots are worn for various purposes, and may be worn with or without a wetsuit.

Thermal protection

In many water sports such as scuba diving, surfing, kayaking, windsurfing, sailing and even fishing, bootees may be worn to keep the feet warm in the same way that a wetsuit would. Insulation is proportional to thickness and thus to how cold the water which the user can tolerate; it may be above or below the standard of 5–6 mm of neoprene. In warmer climates where the thermal qualities of the bootee are not so important, a bootee with a thickness of 2–3.5 mm is common. The leg of the bootee may have a zipper down one side or may be tightened with a velcro strap. Where boots are worn with a wetsuit they are usually tucked under the leg of the suit for streamlining, to help hold the zip closed, and to keep foreign objects out.

Foot protection

A bootee usually has a reinforced sole for walking. Typically, this is a solid rubber compound that is thicker and tougher than the neoprene used for the upper part of the bootee but is still flexible. The reinforced sole provides the wearer with some protection and grip when walking across shingle, coral and other rough surfaces.

For scuba diving

For scuba diving the sole of the bootee should not be so thick that the diver cannot get a fin on over it. Divers wearing bootees use fins with a foot part larger than needed with bare feet. Divers in warm water who do not wear a diving suit sometimes wear bootees so they can wear bigger fins. Diving bootees are typically intended for wear with open-heeled fins, held on by a strap, and usually do not fit into full-footed fins. Neoprene socks may be used with full-footed fins, either to prevent chafing and blisters, or for warmth.

For surfing

For surfing, windsurfing, kitesurfing and similar sports, bootees are typically worn where the weather is so cold that the surfer would lose some degree of functionality in the feet. The bootee should not restrict the ability of a surfer to grip the board with the toes in the desired manner. Split-toe bootees allow for some improvement in this functionality. Reef walkers are small bootees that are only as high as the ankle and generally only 2 to 3.5mm thick. They are designed to allow surfers to get out to waves that break at coral reefs or at rocky beaches.

For kayaking

Several styles of wetsuit boots are commonly used for kayaking. Short-cut boots are frequently used in warmer conditions where the boots help give grip and foot protection while launching and portaging. In cold conditions longer wetsuit boots may be used with a drysuit where they are worn over the rubber drysuit socks.

Gloves

Wetsuit gloves are worn to keep the hands warm and to protect the skin while working. They are available in a range of thicknesses. Thicker gloves reduce manual dexterity and limit feel.[2] Wetsuit gloves are also commonly worn with dry suits. Some divers cut the fingertips of the gloves off on the fingers most used for delicate work like operating the controls on a camera housing. If this is dome, the fingertips are exposed to cold and possible injury, so thin work-gloves may be worn under the insulating gloves.

For cold water use, thicker mittens with a single space for the middle, ring and fifth fingers are available and can provide more warmth at the cost of reducing dexterity.

Buoyancy

Measurements of volume change of neoprene foam used for wetsuits under hydrostatic compression shows that about 30% of the volume, and therefore 30% of surface buoyancy, is lost in about the first 10 m, another 30% by about 60 m, and the volume appears to stabilise at about 65% loss by about 100 m.[10] The total buoyancy loss of a wetsuit is proportional to the initial uncompressed volume. An average person has a surface area of about 2 m2,[28] so the uncompressed volume of a full one piece 6 mm thick wetsuit will be in the order of 1.75 x 0.006 = 0.0105 m3, or roughly 10 litres. The mass will depend on the specific formulation of the foam, but will probably be in the order of 4 kg, for a net buoyancy of about 6 kg at the surface. Depending on the overall buoyancy of the diver, this will generally require 6 kg of additional weight to bring the diver to neutral buoyancy to allow reasonably easy descent The volume lost at 10 m is about 3litres, or 3 kg of buoyancy, rising to about 6 kg buoyancy lost at about 60 m. This could nearly double for a large person wearing a farmer-john and jacket for cold water. This loss of buoyancy must be balanced by inflating the buoyancy compensator to maintain neutral buoyancy at depth.

See also

- Dry suit – Watertight clothing that seals the wearer from cold and hazardous liquids

- Human factors in diving equipment design – Influence of the interaction between the user and the equipment on design

- Rash guard – Stretch garment for protection from abrasion, UV and stings

- Glossary of surfing

Notes

- Nitrogen has a thermal conductivity of 0.024 Wm−1K−1, the same as air – "Thermal conductivity of some common materials". The Engineering ToolBox. 2005. Retrieved August 12, 2009.

- Non-foamed solid neoprene has a thermal conductivity between 0.15 Wm−1K−1 and 0.45 Wm−1K−1 depending on type, not very different from water – Elert, Glenn (2008). "Conduction". The Physics Hypertextbook. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

References

- "How Wetsuits Work". Lomo Watersport. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- Williams, Guy; Acott, Chris J (2003). "Exposure suits: a review of thermal protection for the recreational diver". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. 33 (1). ISSN 0813-1988. OCLC 16986801. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- Barsky, Steven M; Long, Dick; Stinton, Bob (2006). "Dry Suit Diving: A Guide to Diving Dry". Ventura, Calif.: Hammerhead Press. ISBN 0-9674305-6-9. Retrieved June 27, 2017. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kent, Hazen The Rap on Wetsuits in Triathlon trinewbies.com

- "At what temps can you use a wetsuit?". triathlonwetsuitstore.com. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- "Kona Ironman World Championship - All You Need To Know - One To Multi". onetomulti.com. October 10, 2017. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- Ross Tucker; Jonathan Dugas (January 29, 2008). "Exercise in the Cold: Part II A physiological trip through cold water exposure". The Science of Sport. Archived from the original on May 24, 2010. Retrieved November 26, 2009.

- "Thermal conductivity of some common materials". The Engineering ToolBox. 2005. Retrieved August 12, 2009.

- Robert A. Clark; et al. Open Water Diver manual (in Dutch) (1st ed.). Scuba Schools International GmbH. pp. 1–9. ISBN 1-880229-95-1.

- Bardy, Erik; Mollendorf, Joseph; Pendergast, David (October 21, 2005). "Thermal conductivity and compressive strain of foam neoprene insulation under hydrostatic pressure". Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 38 (20): 3832–3840. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/38/20/009.

- Monji K, Nakashima K, Sogabe Y, Miki K, Tajima F, Shiraki K (1989). "Changes in insulation of wetsuits during repetitive exposure to pressure". Undersea Biomed Res. 16 (4): 313–9. PMID 2773163. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- Leckart, Steven (April 15, 2010). "Rip Curl H-Bomb: Heated Wetsuit Stokes Your Fanny When Hanging 10". Wired (website). Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- Bevan, John, ed. (2005). "Section 5.4". The Professional Divers's Handbook (second ed.). 5 Nepean Close, Alverstoke, GOSPORT, Hampshire PO12 2BH: Submex Ltd. p. 242. ISBN 978-0950824260.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Taylor, Michael (May 11, 2008). "Hugh Bradner, UC's inventor of wetsuit, dies". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- Taylor, Michael (May 21, 2008). "Hugh Bradner, Physicist who worked on the Manhattan Project and invented the neoprene wetsuit". The Times. London. Retrieved May 23, 2008.

- Rainey, C. "Wet Suit Pursuit: Hugh Bradner's Development of the First Wet Suit" (PDF). UC San Diego, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives, Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- "Steamer Lane and Some Surf History". Santa Cruz Waves. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- Kampion, Drew; Marcus, Ben (December 2000). "Jack O'Neill – Surfing A to Z". Surfline/Wavetrak, Inc. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- "Oneill – Know Jack". O'Neill Inc. Archived from the original on February 19, 2008. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- Georges Beuchat and Pierre Malaval: FR61926. Vêtement isolant pour séjour dans l'eau en surface ou en plongée. Retrieved on 13 June 2019.

- Georges Beuchat and Pierre Malaval: FR979205. Vêtement isolant pour séjour dans l'eau en surface ou en plongée. Retrieved on 13 June 2019.

- Georges Beuchat and Pierre Malaval: FR1029851. Dispositif de liaison par fermeture automatique des parties jointives d'un vêtement isotherme pour plongée ou autre. Retrieved on 13 June 2019.

- Lillywhites Ltd. Underwater Catalogue 1955, London: Lillywhites Ltd., p. 1.

- Heinke Dolphin wetsuit. Retrieved on 11 June 2019.

- "Gul History". History. May 17, 2014. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- Staff (April 30, 2016). "Open Cell vs Closed Cell Wetsuits". Ninepin Wetsuits. Retrieved February 7, 2018.

- "Steamer Wetsuit". History. May 17, 2014. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- Gallo, Richard L. (June 2017). "Human Skin Is the Largest Epithelial Surface for Interaction with Microbes". The Journal of investigative dermatology. 137 (6): 1213–1214. doi:10.1016/j.jid.2016.11.045. PMID 28395897.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wetsuits. |

| Look up wetsuit in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |