Panic

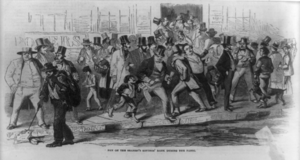

Panic is a sudden sensation of fear, which is so strong as to dominate or prevent reason and logical thinking, replacing it with overwhelming feelings of anxiety and frantic agitation consistent with an animalistic fight-or-flight reaction. Panic may occur singularly in individuals or manifest suddenly in large groups as mass panic (closely related to herd behavior).

_(14785143685).jpg)

Etymology

The word derives from antiquity and is a tribute to the ancient god Pan. One of the many gods in the mythology of ancient Greece, Pan was the god of shepherds and of woods and pastures. The Greeks believed that he often wandered peacefully through the woods, playing a pipe, but when accidentally awakened from his noontime nap he could give a great shout that would cause flocks to stampede. From this aspect of Pan's nature Greek authors derived the word panikos, “sudden fear,” the ultimate source of the English word: "panic".[1] The Greek term indicates the feeling of total fear that is also sudden and often attributed to the presence of a god.[2]

Psychology

In psychology, panic is identified as a disorder and is related strongly to biological and psychological factors and their interactions.[3] A view described one of its incidences as a specific psychological vulnerability of people to interpret normal physical sensations in a catastrophic way.[4] Leonard J. Schmidt and Brooke Warner describe panic as “that terrible, profound emotion that stretches us beyond our ability to imagine any experience more horrible” adding that “physicians like to compare painful clinical conditions on some imagined ‘Richter scale’ of vicious, mean hurt … to the psychiatrist there is no more vicious, mean hurt than an exploding and personally disintegrating panic attack.”[5]

Panic in social psychology is considered infectious since it can spread to a multitude of people and those affected are expected to act irrationally as a consequence.[6] Psychologists identify different types of this panic event with slightly varying descriptions and these include mass hysteria, mass psychosis, mass panic, and social contagion.[7]

An influential theoretical treatment of panic is found in Neil J. Smelser's Theory of Collective Behavior. The science of panic management has found important practical applications in the armed forces and emergency services of the world.

Effects

Prehistoric humans used mass panic as a technique when hunting animals, especially ruminants. Herds reacting to unusually strong sounds or unfamiliar visual effects were directed towards cliffs, where they eventually jumped to their deaths when cornered.

Humans are also vulnerable to panic and it is often considered infectious, in the sense one person's panic may easily spread to other people nearby and soon the entire group acts irrationally, but people also have the ability to prevent and/or control their own and others' panic by disciplined thinking or training (such as disaster drills).

Architects and city planners try to accommodate for the symptoms of panic, such as herd behavior, during design and planning, often using simulations to determine the best way to lead people to a safe exit and prevent congestion (stampedes). The most effective methods are often non-intuitive. A tall column or columns, placed in front of the door exit at a precisely calculated distance, may speed up the evacuation of a large room, as the obstacle divides the congestion well ahead of the choke point.[8]

Many highly publicized cases of deadly panic occurred during massive public events. The layout of Mecca was extensively redesigned by Saudi authorities in an attempt to eliminate frequent stampedes, which kill an average of 250 pilgrims every year.[9] Football stadiums have seen deadly crowd rushes and stampedes, such as at Heysel stadium in Belgium in 1985 with more than 600 casualties, including 39 deaths, and at Hillsborough stadium in Sheffield, England, in 1989 when 96 people were killed in a crush.

See also

- Panic attack – Period of intense fear of sudden onset

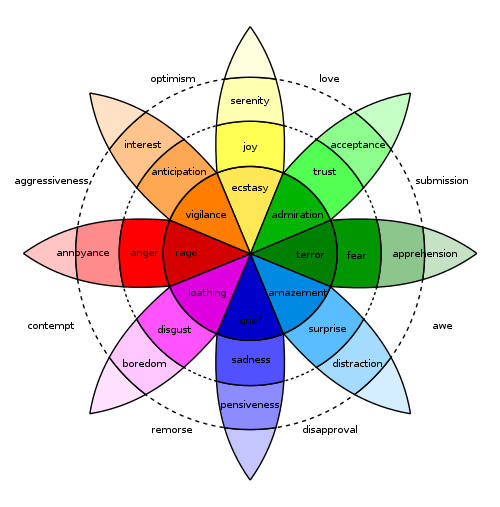

- Anxiety – Unpleasant combination of emotions including fear, apprehension and worry

- Fight-or-flight response

- Angst – Intense feeling of apprehension, anxiety, or inner turmoil

- Collective behavior

- Collective identity

- Emotion – Subjective, conscious experience characterised primarily by psychophysiological expressions, biological reactions, and mental states

- Hysteria – Excess, ungovernable emotion

- Kernel panic

- Moral panic – Feeling of fear spread among many people that some evil threatens the well-being of society

- Financial crisis – Situation in which financial assets suddenly lose a large part of their nominal value

- Panic disorder

- Panic Saturday (Super Saturday), last Saturday before Christmas

- Panic! at the Disco – American rock solo project

Notes

- "Definition of Panic by Merriam-Webster".

- Cavarero, Adriana (2010). Horrorism: Naming Contemporary Violence. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780231144568.

- Barlow, David; Durand, Mark (2012). Abnormal Psychology: An Integrative Approach, 7th edition. Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning. p. 139. ISBN 9781285755618.

- Durand, Mark; Barlow, David; Hofman, Stefan (2018). Essentials of Abnormal Psychology. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning. p. 132. ISBN 9781337619370.

- Leonard J. Schmidt and Brooke Warner (eds), Panic: Origins, Insight, and Treatment (Berkeley CA: North Atlantic Books, 2002), xiii

- Radosavljevic, Vladan; Banjari, Ines; Belojevic, Goran (2018). Defence Against Bioterrorism: Methods for Prevention and Control. Dordrecht: Springer. p. 142. ISBN 9789402412628.

- Heinzen, Thomas; Goodfriend, Wind (2018-03-21). Case Studies in Social Psychology: Critical Thinking and Application. SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781544308890.

- TWAROGOWSKA, M; GOATIN, P; DUVIGNEAU, R. "MACROSCOPIC MODELING AND SIMULATIONS OF ROOM EVACUATION". arXiv:1308.1770.

- Castelvecchi, Davide (2007-04-07), "Formula for Panic: Crowd-motion findings may prevent stampedes", Science News Online

External links

| Look up panic in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Panic |

- Panic! How it works and What To Do About It — by Bruce Tognazzini.

- "Panic: Myth or Reality?" — Professor Lee Clarke, Contexts Magazine, 2002. (Article available as PDF from Lee Clarke's website)