Spearfishing

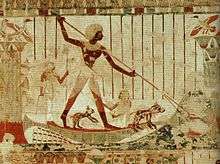

Spearfishing is a method of fishing that has been used throughout the world for millennia. Early civilizations were familiar with the custom of spearing fish from rivers and streams using sharpened sticks.

Currently spearfishing makes use of elastic powered spearguns and slings, or compressed gas pneumatic powered spearguns, to strike the hunted fish. Specialised techniques and equipment have been developed for various types of aquatic environments and target fish.

Spearfishing may be done using free-diving, snorkelling, or scuba diving techniques, but spearfishing while using scuba equipment is illegal in some countries. The use of mechanically powered spearguns is also outlawed in some countries and jurisdictions. Spearfishing is highly selective, normally uses no bait and has no by-catch.

History

.jpg)

Spearfishing with barbed poles (harpoons) was widespread in palaeolithic times.[1] Cosquer Cave in Southern France contains cave art over 16,000 years old, including drawings of seals which appear to have been harpooned.

There are references to fishing with spears in ancient literature; though, in most cases, the descriptions do not go into detail. An early example from the Bible is in Job 41:7: Canst thou fill his [Leviathan] skin with barbed irons? or his head with fish spears?.

The Greek historian Polybius (ca 203 BC–120 BC), in his Histories, describes hunting for swordfish by using a harpoon with a barbed and detachable head.[2]

Greek author Oppian of Corycus wrote a major treatise on sea fishing, the Halieulica or Halieutika, composed between 177 and 180. This is the earliest such work to have survived intact. Oppian describes various means of fishing including the use of spears and tridents.[3]

In a parody of fishing, a type of gladiator called retiarius carried a trident and a casting-net. He fought the murmillo, who carried a short sword and a helmet with the image of a fish on the front.[4]

Copper harpoons were known to the seafaring Harappans[5] well into antiquity.[6] Early hunters in India include the Mincopie people, aboriginal inhabitants of India's Andaman and Nicobar islands, who have used harpoons with long cords for fishing since early times.[7]

Poseidon/Neptune sculpture in Copenhagen Port

Poseidon/Neptune sculpture in Copenhagen Port

Dutch fishermen using tridents in the 17th century

Dutch fishermen using tridents in the 17th century

Traditional

Spear fishing is an ancient method of fishing and may be conducted with an ordinary spear or a specialised variant such as an eel spear[8][9] or the trident. A small trident-type spear with a long handle is used in the American South and Midwest for gigging bullfrogs with a bright light at night, or for gigging carp and other fish in the shallows.

Modern

Traditional spear fishing is restricted to shallow waters, but the development of the speargun, diving mask and swimfins allows fishing in deeper waters. With practice, some freedivers are able to hold their breath for up to four minutes; a diver with underwater breathing equipment can dive for much longer periods.

In the 1920s, sport spearfishing using only watertight swimming goggles became popular on the Mediterranean coast of France and Italy. This led to development of the modern diving mask, fins and snorkel. Modern scuba diving had its genesis in the systematic use of rebreathers by Italian sport spearfishers during the 1930s. This practice came to the attention of the Italian Navy, which developed its frogman unit, which affected World War II.[10]

By 1940 small groups of people in California, USA had been spearfishing for less than 10 years. Most used imported gear from Europe, while innovators Charlie Sturgill, Jack Prodanovich,[11] and Wally Potts[12] invented and built innovative equipment for California divers.[11]

During the 1960s, attempts to have spearfishing recognised as an Olympic sport were unsuccessful. Instead, two organisations, the International Underwater Spearfishing Association[13] (IUSA) and the International Bluewater Spearfishing Records Committee (IBSRC), list world record catches by species according to rules to ensure fair competition. Spearfishing is illegal in many bodies of water, and some locations only allow spearfishing during certain seasons.

Conservation

Spearfishing has been implicated in local disappearances of some species, including the Atlantic goliath grouper on the Caribbean island of Bonaire, the Nassau grouper in the barrier reef off the coast of Belize and the giant black sea bass in California, which have all been listed as endangered . Modern spearfishing has shifted focus onto catching only what one needs and targeting sustainable fisheries. As gear evolved in the 1960s and 1970s spearfishermen typically viewed the ocean as an unlimited resource and often sold their catch. This practice is now heavily frowned upon in prominent spearfishing nations for promoting unsustainable methods and encouraging taking more fish than is needed. In countries such as Australia and South Africa where the activity is regulated by state fisheries, spearfishing has been found to be the most environmentally friendly form of fishing due to being highly selective, having no by-catch, causing no habitat damage, nor creating pollution or harm to protected endangered species.[14] In 2007, the Australian Bluewater Freediving Classic became the first spearfishing tournament to be accredited and was awarded 4 out of 5 stars based on environmental, social, safety and economic indicators.[15]

Shore diving

Shore diving is perhaps the most common form of spearfishing [16][17] and simply involves entering and exiting the sea from beaches or headlands and hunting around ocean structures,[18] usually reef, but also rocks, kelp or sand. Usually shore divers hunt at depths of 5–25 metres (16–82 ft), depending on location. In some locations, divers can experience drop-offs from 5 to 40 metres (16 to 131 ft) close to the shore line. Sharks and reef fish can be abundant in these locations. In subtropical areas, sharks may be less common, but other challenges face the shore diver, such as managing entry and exit in the presence of big waves. Headlands are favoured for entry because of their proximity to deeper water, but timing is important so the diver does not get pushed onto rocks by waves. Beach entry can be safer, but more difficult due the need to repeatedly dive through the waves until the surf line is crossed. Divers may enter from a relatively exposed headland, for convenience, then swim to a more protected part of the shore for their exit from the water.

Shore dives produce mainly reef fish, but oceangoing pelagic fish are also caught from shore dives in some places, and can be specifically targeted.

Shore diving can be done with trigger-less spears such as pole spears or Hawaiian slings, but more commonly triggered devices such as spearguns. Speargun setups to catch and store fish include speed rigs and fish stringers.

Boat diving

Boats, ships, kayaks, or even jetski can be used to access offshore reefs or ocean structure. Man-made structures such as oil rigs and Fish Aggregating Devices (FADs) are also fished. Sometimes a boat is necessary to access a location that is close to shore, but inaccessible by land.

Methods and gear used for boat diving are similar to shore diving or blue water hunting, depending on the target prey.

Boat diving is practised worldwide. Hot spots include Mozambique, the Three Kings islands of New Zealand (yellowtail), Gulf of Mexico oil rigs (cobia, grouper) and the Great Barrier Reef (wahoo, dogtooth tuna). The deepwater fishing grounds off Cape Point, (Cape Town, South Africa) have become popular with trophy hunting, freediving spearfishers in search of Yellowfin Tuna.

Blue water hunting

Blue water hunting involves diving in open ocean waters for pelagic species. It involves accessing usually very deep and clear water and chumming for large pelagic fish species such as marlin, tuna, wahoo, or giant trevally. Blue water hunting is often conducted in drifts; the boat driver drops divers and allow them to drift in the current for up to several kilometres before collecting them. Blue water hunters can go for hours without seeing any fish, and without any ocean structure or a visible bottom the divers can experience sensory deprivation and have difficulty determining the size of a solitary fish. One technique to overcome this is to note the size of the fish's eye in relation to its body. Large specimens have a proportionally smaller eye.

The creation of the Australian Bluewater Freediving Classic in 1995 in northern New South Wales was a way of creating interest and promotion of this format of underwater hunting, and contributed to the formation of the International Bluewater Spearfishing Records Committee. The IBSRC formed in 1996, was the first dedicated organization worldwide, created by recognized world leaders in blue-water hunting, to record the capture of pelagic species by blue-water hunters.

Notably, some blue water hunters use large multi-band wooden guns and make use of breakaway rigs to catch and subdue their prey. If the prey is large and still has fight left after being subdued, a second gun can provide a kill shot at a safe distance. This is acceptable to IBSRC and IUSA regulations as long as the spearo loads it himself in the water.

Blue water hunting is conducted worldwide, but notable hot spots include Mozambique (dogtooth tuna, wahoo and giant turrum), South Africa (Yellowfin tuna, Spanish Mackerel, wahoo, marlin and giant turrum), Australia (dogtooth tuna, wahoo and Spanish Mackerel) and the South Pacific (dogtooth tuna). Tanzania has been removed as a notable hot spot as spearfishing is illegal according to the laws and regulations of both Tanzania and Zanzibar.

Freshwater hunting

Many US states allow spearfishing in lakes and rivers, but nearly all of them restrict divers to shooting only rough fish such as carp, gar, bullheads, suckers, etc. A few US states do allow the taking of certain gamefish such as sunfish, crappies, striped bass, catfish and walleyes. Freshwater hunters typically have to deal with widely varying seasonal changes in water clarity due to flooding, algae blooms and lake turnover. Some especially hardy midwestern and north central scuba divers go spearfishing under the ice in the winter when water clarity is at its best.

In the summer the majority of freshwater spearfishermen use snorkelling gear rather than scuba since many of the fish they pursue are in relatively shallow water. Carp shot by freshwater spear fishermen typically end up being used as fertilizer, bait for trappers, or are occasionally donated to zoos.

Without diving

Spearfishing with a hand-held spear from land, shallow water or boat has been practised for thousands of years. The fisher must account for optical refraction at the water's surface, which makes fish appear higher in their line of sight than they are. By experience, the fisher learns to aim lower. Calm and shallow waters are favored for spearing fish from above the surface, as water clarity is of utmost importance. Many people who grew up on farms in the midwest U.S. in the 1940s-'60s recall going spearing for carp with pitchforks when their fields flooded in the spring. Spearfishing in this manner has some similarities to bowfishing.[19]

Equipment

This is a list of equipment commonly used in spearfishing. Not all of it is necessary and spearfishing is often practised with minimal gear.

- Speargun

- A speargun is an underwater fishing implement designed to fire a spear at fish. The most popular spearguns are powered by natural latex rubber bands, while pneumatic powered guns are also used, but less powerful.[20]

- Polespear

- Pole spears, or hand spears, consist of a long shaft with point at one end and an elastic loop at the other for propulsion. They also come in a wide variety, from aluminum or titanium metal, to fiberglass or carbon fiber. Often they are screwed together from smaller pieces or able to be folded down for ease of transport. In 1951 Charlie Sturgill beat the competition (who were all using spearguns) with his own pole spear design.[21]

- Hawaiian slings

- Hawaiian slings consist of an elastic band attached to a tube, through which a spear is launched.[22]

- Wet suit

- Wetsuits designed specifically for spearfishing are often two-piece (jacket and high waisted pants or 'long-john' style pants with shoulder straps) and are black or are fully or partially camouflage.

- Weight belt or weight vest

- These are used to compensate for wetsuit buoyancy and help the diver descend to depth. Rubber belts which can be quickly released in an emergency have proven to be particularly popular for spearfishing worldwide. This is because the rubber stretches when fitted and retracts as the body and wetsuit compress underwater, keeping them in place more effectively than non-stretch webbing belts, which tend to slide around more underwater as they loosen with depth.[23] Most spearfishing equipment manufacturers now offer rubber weight belts.

- Fins

- Fins for freedive spearfishing are much longer than those used in scuba to aid in fast ascent. Typically a closed foot design is used by freediving (snorkelling) spearos, usually worn with neoprene socks, while open foot designs (which allow diving boots to be worn) are more popular with scuba divers.

- Knife or cutters

- A knife is carried as a safety precaution in case the diver becomes tangled in a spearline or floatline. It can also be used as an ikejime or kill spike.

- Ikejime or kill spike

- In lieu of a knife, a sharpened metal spike can be used to kill the fish quickly and humanely upon capture. This action reduces interest from sharks by stopping the fish from thrashing. Ikejime is a Japanese term and is a method traditionally used by Japanese fishermen. Killing the fish quickly is believed to improve the flavor of the flesh by limiting the buildup of adrenaline in the fish's muscles.

- Buoy or float

- A buoy is usually tethered to the spearfisher's speargun or directly to the spear. A buoy helps to subdue large fish. It can also assist in storing fish. But is more importantly used as a safety device to warn boat drivers there is diver in the area - usually by being large, brightly colored and flying a dive flag (the red flag with white diagonal stripe in the USA or the blue & white "alpha" flag elsewhere in the world). A typical spearo dive float will be torpedo-shaped, orange or red in colour with a volume of between 7 and 36 litres and display a dive flag on a short mast. However, other designs, such as inflatable mini-dinghy, planche (box), Tommy Botha (big game) and body-boards are also used.

- Floatline

- A floatline connects the buoy to the speargun or to the weight-belt. Often made from braided polyester, they are also frequently made from mono-filament encased in an airtight plastic tube, or made from stretchable bungee cord.

- Gloves

- Gloves protect the hands when retrieving fish from coral or rock crevices, when loading the bands on rubber powered spearguns and from the teeth and spines of struggling fish. They are also used for thermal protection in colder water.

- Fish stringer

- Used to store speared fish while diving. Usually a length of cable, cord, string or monofilament terminated by a loop (and sometimes a swivel) at one end and a large stainless steel pin/spike at the other. The pin is typically 15–30 cm long, 4-8mm diameter, with a sharp point at one end, and with the cable threaded through a hole, usually in the middle, so the spike functions as a toggle once threaded. The pin can optionally be used as an iki jime spike, to dispatch speared fish. It can alternatively be a large, shaped loop of stainless steel. The stringer may be attached to the dive float, especially in areas of high shark activity, although some divers will use a clip to attach their stringer to their weight belt, or the base of their speargun.[24]

- Snorkel and diving mask

- Spearfishing snorkels and diving masks are similar to those used for scuba diving, although the masks usually have two lenses and a lower internal volume.

- Diver down flag

- The "diver down" flag (also called a "dive flag") is a safety flag used on the water to indicate to other boats that there is a diver below. When in use, it signals to other vessels to keep clear, watch for divers in the water, and operate at a slow speed.

Management

Spearfishing is intensively managed throughout the world.

Australia allows only recreational spearfishing and generally only breath-hold free diving. State & territory governments impose numerous restrictions, demarcating Marine Protected Areas, Closed Areas, Protected Species, size/bag limits and equipment. The body principally concerned with spearfishing is the Australian Underwater Federation, Australia's peak recreational diving body. The AUF's vision for spearfishing is "Safe, Sustainable, Selective, Spearfishing". The AUF provides membership, advocacy and organises competitions.[25]

Norway has a relatively large ratio of coastline to population, and has one of the most liberal spearfishing rules in the northern hemisphere. Spearfishing with scuba gear is widespread among recreational divers. Restrictions in Norway are limited to anadrome species, like Atlantic salmon, sea trout, and lobster.[26]

In Mexico a regular fishing permit allows spearfishing, but not electro-mechanical spearguns. Spearfishing with scuba gear is illegal and the use of power heads as well. Penalties are severe and include fines, confiscation of gear and even imprisonment.[27]

United States has different spearfishing regulations for each state. In Florida spearfishing is restricted to several hundred yards offshore in many areas and the usage of a powerhead is prohibited within state waters. Many types of fish are currently under heavy bag restrictions. In California only recreational spearfishing is allowed. California also imposes numerous restrictions, demarcating Marine protected areas, closed areas, protected species, size/bag limits and equipment.[28] Spearfishing in Puerto Rico has its own set of rules.

In the UK, while spearfishing is not explicitly regulated, it is instead subject to both local (typically local bye-laws) and national-level legislation relating to permitted fish species and minimum size limits. For example, it is not permitted to spearfish in freshwater and the non-tidal reaches of rivers.

Under recent EU guidelines, recreational spearfishing is now explicitly permitted in the EU's Atlantic waters.

Notable spearfishers

This is an alphabetic list of spearfishers who are confirmed by a reliable source or an existing Wikipedia article.

- Rob Allen - South Africa[29]

- Tommy Botha - South Africa[30]

- Peter Crawford - England, 13 times UK champion[31]

- Ben Cropp – Australian documentary filmmaker, conservationist and spearfisherman

- Ian Fleming – English author, journalist and naval intelligence officer - England; author of the James Bond books and Chitty Chitty Bang Bang

- Wally Gibbons[32]

- Guy Gilpatric

- James Grant - New Zealand[33]

- David J. Hochman - World Record Holder, Men's Speargun, Striped Bass, 31.0 kg/68.4 lbs; Men's Polespear, Striped Bass, 23.8 kg/52.4 lbs[34]

- Harold Holt – Australian politician, 17th Prime Minister of Australia - Australian prime minister[35]

- Cameron Kirkconnell - 12x world record holder[36][29]

- Mohammed Jassim Al-Kuwari - Qatar[29]

- George "Doc" Lopez

- Terry Maas - USA[29]

- Barry Paxman - Australia[29]

- Raymond Pulvénis - France; equipment inventor and manufacturer; author of first French book entirely dedicated to spearfishing (La chasse aux poissons, 1940)[37][38]

- Dr Adam Smith - Australia [39]

- Charlie Sturgill - USA; US National spearfishing champion 1951; innovator of modern spearfishing equipment[21]

- Ron Taylor – Australian diver and shark cinematographer

- Valerie Taylor – Australian underwater photographer

- Rob Torelli - Australia, 9 times Australian champion[40]

- Daryl Wong - USA equipment maker[41]

See also

- Underwater target shooting – Breathhold underwater sport of target shooting with a speargun in a swimming pool.

References

- Guthrie, Dale Guthrie (2005) The Nature of Paleolithic Art. Page 298. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-31126-0

- Polybius, "Fishing for Swordfish", Histories Book 34.3 (Evelyn S. Shuckburgh, translator). London, New York: Macmillan, 1889. Reprint Bloomington, 1962.

- "Oppian, Halieutica"

- "Retiarius"

- Ray, Himanshu Prabha (2003). The Archaeology of Seafaring in Ancient South Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01109-4. page 93

- F.R. Allchin in South Asian Archaeology 1975: Papers from the Third International Conference of the Association of South Asian Archaeologists in Western Europe, Held in Paris (December 1979) edited by J.E.van Lohuizen-de Leeuw. Brill Academic Publishers, Incorporated. Page 106 ISBN 90-04-05996-2

- Edgerton; et al. (2002). Indian and Oriental Arms and Armour. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-42229-1. page 74

- "Water: The Riches of Clare". www.clarelibrary.ie. Clare County Library. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- Alice Ross. "Getting a Feel for the Eel". Journal of Antiques and Collectibles. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- Quick, D. (1970). "A History Of Closed Circuit Oxygen Underwater Breathing Apparatus". Royal Australian Navy, School of Underwater Medicine. RANSUM-1-70. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- "San Diego Union-Tribune Obituaries: Complete listing of San Diego Union-Tribune Obituaries powered by Legacy.com". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- "Wally Potts, 83; Pioneering Diver, Spear Fisherman". latimes. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- "iusarecords.com". iusarecords.com. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- Smith, Adam; Nakaya, Seiji (21–24 May 2002). Spearfishing – is it ecologically sustainable? (PDF). 3rd World Recreational Fishing Conference. 21–24 May 2002. pp. 19–22. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- Sawynok, Bill; Diggles, Ben; Harrison, John (2008). 2006/057: Development of a national environmental management and accreditation system for business/public recreational fishing competitions (PDF). Frenchville Qld: Recfish Australia. pp. 15, 32. ISBN 978-0-9775165-5-1. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- http://www.noobspearo.com/the-vault-blog/guide-for-shore-dive-spearfishing-part2/

- http://ultimatespearfishing.com/page/spearfishing-shore-dive-tips-tricks

- http://www.noobspearo.com/the-vault-blog/shore-dive-spearfishing-part-1

- Otto Gabriel; Klaus Lange; Erdmann Dahm; Thomas Wendt (26 August 2005). Fish Catching Methods of the World. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-85238-280-6.

- "Rubber vs Pneumatic Spearguns". Adreno Spearfishing Blog - Speargun & Wetsuit Online Megastore - Spearfishing - Freediving - Snorkeling - Brisbane - Australia. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- Sellers, Bob (August 31, 2004). "Charlie Sturgill" (PDF). fathomiers.net. Retrieved April 24, 2017.

- Steven M. Barsky (1997). Spearfishing for Skin and Scuba Divers. Best Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-941332-59-0.

- Bennett, Travis. "Spearfishing tips - The correct way to setup your weight belt for spearfishing". www.maxspearfishing.com. Max Spearfishing. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- Bennett, Travis. "Spearfishing accessories - Why You Need a Spearfishing Stringer". www.maxspearfishing.com. Max Spearfishing. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- "Australian Underwater Federation - Spearfishing". Australian Underwater Federation. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Spearfishing in Norway Archived September 27, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Sportfishing regulations, Conapesca Mexico San Diego Office". Conapesca San Diego. Archived from the original on 2013-09-06. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- "Ocean Fishing: Laws and Regulations". Dfg.ca.gov. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- "Onefish Legends". Spearo DvD. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- Mass, Terry (2005). "South African legend opens the tuna grounds". BlueWater Freedivers. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- "Jerseyman wins Open Spearfishing title". Jersey Spearfishing Club. 2003. Retrieved 15 September 2014.

- "In the depths of adventure". Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- https://www.smh.com.au/world/man-fights-off-shark-then-stitches-himself-up-20140127-hva2g.html

- "International Underwater Spearfishing Association World Record 31.0 kg, 68.4 lbs Bass, Striped Morone saxatilis Record Category: Men Speargun". International Underwater Spearfishing Association. July 4, 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- "National and personal tragedy". The Australian Women's Weekly. 35 (32). Australia, Australia. 3 January 1968. p. 4. Retrieved 2 April 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- "Spearfishing with Cameron Kirkconnell". Onefish. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- Vianney Mascret (2010) L’aventure sous-marine : Histoire de la plongée sous-marine de loisir en scaphandre autonome en France (1865-1985). Thesis, Claude Bernard University, Lyon. p. 168. Full-text document at http://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/docs/00/83/90/91/PDF/TH2010_Mascret_Vianney.pdf. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- Patrick Mouton (1987) | Roger Pulvénis « Père » de la chasse sous-marine, le journal de la mer. Retrieved on 12 January 2020.

- Smith, Adam (2000). "Underwater fishing in Australia and New Zealand".

- "Spearfishing Champion Trophies". Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- "Wong Spearguns". Retrieved 29 April 2020.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Spearfishing. |

- Jones, Len (2002). Len Jones' guide to freedive spearfishing (Australian ed.). Adrenaline Spearfishing Supplies. ISBN 978-0-9580308-0-9.

- Smith, Adam K (2000). Underwater fishing in Australia and New Zealand. Mountain Ocean & Travel Publications. ISBN 978-0-646-40642-8.

- Spearfishing is it ecologically sustainable? A paper given at the World Recreational Fishing Conference, Darwin, Australia by Adam Smith and Seji Nakaya

- Terry Maas (1998). Bluewater Hunting & Freediving. Ventura, CA: BlueWater Freedivers. ISBN 0-9644966-3-1.