HMS A1

HMS A1 was the Royal Navy's first British-designed submarine, and their first to suffer fatal casualties.

HMS A1 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS A1 |

| Builder: | Vickers, Barrow-in-Furness |

| Laid down: | 19 February 1902[1] |

| Launched: | 9 July 1902 |

| Fate: | Lost, 1911. Wreck rediscovered 1989. |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | A-class submarine |

| Type: | Submarine |

| Displacement: |

|

| Length: | 103.25 ft (31.47 m) |

| Beam: | 11.9 ft (3.6 m) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: |

|

| Range: |

|

| Complement: | 11 (2 officers and 9 ratings) |

| Armament: | 2 × 18 in (450 mm) torpedo tubes (bow, four torpedoes)[2] |

She was the lead ship of the first British A-class submarines and the only one to have a single bow torpedo tube. She was actually sunk twice: first in 1904 when she became the first submarine casualty, with the loss of all hands; however, she was recovered, but sank again in 1911, this time when she was unmanned. The wreck was discovered in 1989 and is now a protected wreck.[3]

Design and construction

She was an enlarged and improved Holland-class submarine–40 ft (12 m) longer than the Royal Navy's five "Holland"-type boats. The most notable improvement was the addition of a conning tower.[1] Subsequent A-class boats were even larger and differed from her in several respects.

Like all members of her class, she was built at Vickers, Barrow-in-Furness. She was launched on 9 July 1902.[4]

Before she left the yard she suffered from a hydrogen explosion.[5] Later while under tow to Portsmouth to join with the rest of the navy's submarines, seawater managed to reach her batteries, which gave off chlorine gas, forcing the evacuation of the vessel.[5]

Casualty, recovery, loss and rediscovery

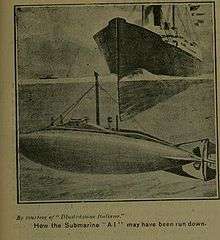

She was accidentally sunk in the Solent on 18 March 1904 whilst carrying out a practice attack on the protected cruiser HMS Juno by being struck on the starboard side of the conning tower by a mail steamer, SS Berwick Castle, which was en route from Southampton to Hamburg. She sank in only 39 ft (12 m) of water, but the boat flooded and the entire crew was drowned.[6] One consequence was that all subsequent Royal Navy submarines were equipped with a watertight hatch at the bottom of the conning tower.[7]

She was raised on 18 April 1904 and repaired and re-entered service. Following a petrol explosion in August 1910, she was converted to a testbed for the Admiralty's Anti-Submarine Committee. She was lost a year later when running submerged but unmanned under automatic pilot. Although the position of her sinking was known at the time, all efforts to locate her were fruitless. It was not until 1989 that the wreck was discovered by a local fisherman at Bracklesham Bay, approximately 5 mi (8.0 km) away.[8] It is thought that she was only partially flooded when she sank, and the resulting partial buoyancy meant that the wreck moved in the strong local currents. The wreck was designated under the Protection of Wrecks Act on 26 November 1998[9] and redesignated to extend the area covered on 5 October 2004.[10]

See also

- Bibliography of 18th-19th century Royal Naval history

References

- Submarine Heritage Centre

- Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century Weapons and Warfare (London: Phoebus, 1978), Volume 1, p.1, "A-1".

- The Advisory Committee for Historic Wreck Sites Annual Report for 2005

- "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times (36816). London. 10 July 1902. p. 10.

- Gray, Edwyn (2003). Disasters of the Deep A Comprehensive Survey of Submarine Accidents & Disasters. Leo Cooper. p. 49. ISBN 0-85052-987-5.

- Submarine losses 1904 to present day RN submarine museum website

-

- Innes McCartney (2002). Lost Patrols: Submarine Wrecks of the English Channel.

- Advisory Committee on Historic Wrecks Report for 1999-2000 Archived 2008-03-06 at the UK Government Web Archive

- Statutory instrument 1998 no 2708 protecting wreck of HMS A1

- Statutory instrument 2004 no 2395

External links

- The Royal Navy Submarine Museum

- First loss article from Submariners Association, Barrow in Furness branch

- 1902-1910 A, B and C Class from Submariners Association, Barrow in Furness branch

- Wessex Archaeology multibeam sonar image of the wreck of HMS A1 surveyed in 2003 and later images from a dive

- 2001 Annual HWTMA public lecture given by John Bingeman

- In peril beneath the sea Hampshire and Dorset shipwrecks website

- A-class submarines on Battlecruisers.co.uk

- Photo of A1 in Portsmouth 1903, from MaritimeQuest website

|

| Shipwrecks |

|

|---|---|

| Other incidents |

|

| Shipwrecks |

|

|---|---|

| Other incidents |

|

1909 | |

| Shipwrecks |

|

|---|---|

| Other incidents |

|

1910 | |