Wheelchair rugby

Wheelchair rugby (originally murderball, and known as quad rugby in the United States) is a team sport for athletes with a disability. It is practised in over twenty-five countries around the world and is a summer Paralympic sport.

The US name is based on the requirement that all wheelchair rugby players need to have disabilities that include at least some loss of function in at least three limbs. Although most have spinal cord injuries, players may also qualify through multiple amputations, neurological disorders or other medical conditions. Players are assigned a functional level in points, and each team is limited to fielding a team with a total of eight points.

Wheelchair rugby is played indoors on a hardwood court, and physical contact between wheelchairs is an integral part of the game. The rules include elements from wheelchair basketball, ice hockey, handball and rugby league.

The sport is governed by the International Wheelchair Rugby Federation (IWRF) which was established in 1993.

History

Wheelchair rugby was created to be a sport for persons with quadriplegia in 1976 by five Canadian wheelchair athletes, Jerry Terwin, Duncan Campbell, Randy Dueck, Paul LeJeune and Chris Sargent, in Winnipeg, Manitoba.[1]

At that time, wheelchair basketball was the most common team sport for wheelchair users. That sport's physical requirement for players to dribble and shoot baskets relegated quadriplegic athletes, with functional impairments to both their upper and lower limbs, to supporting roles. The new sport — originally called murderball due to its aggressive, full-contact nature — was designed to allow quadriplegic athletes with a wide range of functional ability levels to play integral offensive and defensive roles.

Murderball was first introduced into Australia in 1982. The Australian team competing in the Stoke Mandeville games in England were invited by the Canadians to select a team to play them in a demonstration game. After receiving limited instructions on the rules and skills of the game the "contest" began. Following a fast and very competitive exchange, Australia won. The game was then born and brought back to Australia where it has flourished.

Murderball was introduced to the United States in 1979[2] by Brad Mikkelsen. With the aid of the University of North Dakota's Disabled Student Services, he formed the first American team, the Wallbangers. The first North American competition was held in 1982.

In the late 1980s, the name of the sport outside the United States was officially changed from Murderball to Wheelchair Rugby. In the United States, the sport's name was changed to Quad Rugby.

The first international tournament was held in 1989 in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, with teams from Canada, the United States and Great Britain. In 1990, Wheelchair Rugby first appeared at the International Stoke Mandeville Games as an exhibition event,[3] and in 1993 the sport was recognized as an official international sport for athletes with a disability by the International Stoke Mandeville Wheelchair Sports Federation (ISMWSF). In the same year, the International Wheelchair Rugby Federation (IWRF) was established as a sports section of ISMWSF to govern the sport. The first IWRF World Wheelchair Rugby Championships were held in Nottwil, Switzerland, in 1995 and wheelchair rugby appeared as a demonstration sport at the 1996 Summer Paralympics in Atlanta.

The sport has had full medal status since the 2000 Summer Paralympics in Sydney, Australia and there are now twenty-five active countries in international competition, with several others developing the sport.

Rules

Wheelchair rugby is mostly played by two teams of up to twelve players. Only four players from each team may be on the court at any time. It is a mixed-gender sport, and both male and female athletes play on the same teams.

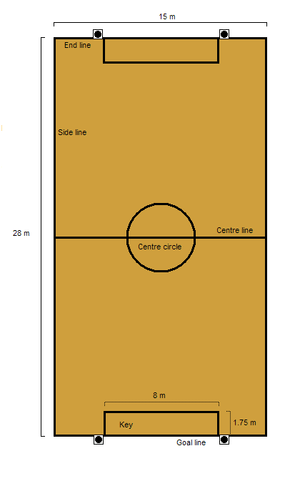

Wheelchair rugby is played indoors on a hardwood court of the same measurements as a regulation basketball court — 28 metres long by 15 metres wide. The required court markings are a centre line and circle, and a key area measuring 8 metres wide by 1.75 metres deep at each end of the court.

The goal line is the section of the end line within the key. Each end of the goal line is marked with a cone-shaped pylon. Players score by carrying the ball across the goal line. For a goal to count, two wheels of the player's wheelchair must cross the line while the player has possession of the ball.

A team is not allowed to have more than three players in their own key while they are defending their goal line. Offensive players are not permitted to remain in the opposing team's key for more than ten seconds.

A player with possession of the ball must bounce or pass the ball within ten seconds.

A team's back court is the half of the court containing the goal they are defending; their front court is the half containing the goal they are attacking. Teams have twelve seconds to advance the ball from their back court into the front court and a total of forty seconds to score a point or concede possession.

Physical contact between wheelchairs is permitted, and forms a major part of the game. However, physical contact between wheelchairs that is deemed dangerous — such as striking another player from behind — is not allowed. Direct physical contact between players is not permitted.

Fouls are penalized by either a one-minute penalty, for defensive fouls and technical fouls, or a loss of possession, for offensive fouls. In some cases, a penalty goal may be awarded in lieu of a penalty. Common fouls include spinning (striking an opponent's wheelchair behind the main axle, causing it to spin horizontally or vertically), illegal use of hands or reaching in (striking an opponent with the arms or hands), and holding (holding or obstructing an opponent by grasping with the hands or arms, or falling onto them).

Wheelchair rugby games consist of four eight-minute quarters. If the game is tied at the end of regulation play, three-minute overtime periods are played.

Much like able-bodied rugby matches, highly competitive wheelchair rugby games are fluid and fast-moving, with possession switching back and forth between the teams while play continues. The game clock is stopped when a goal is scored or in the event of a violation — such as the ball being played out of bounds — or a foul. Players may only be substituted during a stoppage in play.

Equipment

Wheelchair rugby is played in a manual wheelchair. The rules include detailed specifications for the wheelchair. Players use custom-made sports wheelchairs that are specifically designed for wheelchair rugby. Key design features include a front bumper, designed to help strike and hold opposing wheelchairs, and wings, which are positioned in front of the main wheels to make the wheelchair more difficult to stop and hold. All wheelchairs must be equipped with spoke protectors, to prevent damage to the wheels, and an anti-tip device at the back.

New players and players in developing countries sometimes play in wheelchairs that have been adapted for wheelchair rugby by the addition of temporary bumpers and wings.

Wheelchair rugby uses a regulation volleyball typically of a 'soft-touch' design, with a slightly textured surface to provide a better grip. The balls are normally over-inflated compared to volleyball, to provide a better bounce. The official ball of the sport from 2013-2016 is the Molten soft-touch volleyball, model number WR58X.[4] Players use a variety of other personal equipment, such as gloves and applied adhesives to assist with ball handling due to their usually impaired gripping ability, and various forms of strapping to maintain a good seating position.

Classification

To be eligible to play wheelchair rugby, athletes must have some form of disability with a loss of function in both the upper and lower limbs.[5] The majority of wheelchair rugby athletes have spinal cord injuries at the level of their cervical vertebrae. Other eligible players have multiple amputations, polio, or neurological disorders such as cerebral palsy, some forms of muscular dystrophy, or Guillain–Barré syndrome, among other medical conditions.

Players are classified according to their functional level and assigned a point value ranging from 0.5 (the lowest functional level) to 3.5 (the highest). The total classification value of all players on the court for a team at one time cannot exceed eight points.

The classification process begins with an assessment of the athlete's level of disability to determine if the minimum eligibility requirements for wheelchair rugby are met. These require that an athlete have a neurological disability that involves at least three limbs, or a non-neurological disability that involves all four limbs. The athlete then completes a series of muscle tests designed to evaluate the strength and range of motion of the upper limbs and trunks. A classification can then be assigned to the athlete. Classification frequently includes subsequent observation of the athlete in competition to confirm that physical function in game situations reflects what was observed during muscle testing.

Athletes are permitted to appeal their classification if they feel they have not been properly evaluated. Athletes can be granted a permanent classification if they demonstrate a stable level of function over a series of classification tests.

Wheelchair rugby classification is conducted by personnel with medical training, usually physicians, physiotherapists, or occupational therapists. Classifiers must also be trained in muscle testing and in the details of wheelchair rugby classification.

Active countries

As of September 2015 there are twenty-eight active countries playing wheelchair rugby,[6] divided into three zones:

| Zone number | Area | Country |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Americas | Argentina |

| Brazil | ||

| Canada | ||

| Chile | ||

| Colombia | ||

| Mexico | ||

| United States | ||

| 2 | Europe | Austria |

| Belgium | ||

| Czech Republic | ||

| Denmark | ||

| Finland | ||

| France | ||

| Germany | ||

| Great Britain | ||

| Hungary | ||

| Ireland | ||

| Italy | ||

| Netherlands | ||

| Poland | ||

| Russia | ||

| Sweden | ||

| Switzerland | ||

| 3 | Asia / Oceania | Australia |

| China | ||

| Israel | ||

| Japan | ||

| New Zealand | ||

| South Korea | ||

| South Africa |

International competitions

The major wheelchair rugby international competitions are Zone Championships, held in each odd-numbered year, and the World Championships held quadrennially in even-numbered years. Wheelchair rugby is also an included sport in regional events such as the Parapan American Games.[7]

Since 2000, it has been one of the sports of the Summer Paralympic Games.

| Year | Event | City | Country | 1st place | 2nd place | 3rd place |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | European Zone Championship | Vejle | Denmark | Great Britain | Denmark | France |

| 2018 | World Championship | Sydney | Autralia | Japan | Australia | United States |

| 2017 | European Zone Championship | Koblenz | Germany | Great Britain | Sweden | France |

| 2016 | Paralympic Games | Rio de Janeiro | Brazil | Australia | United States | Japan |

| 2015 |

Parapan Am Games[10] | Toronto | Canada | Canada | United States | Colombia |

| European Zone Championship | Nastola | Finland | Great Britain | Sweden | Denmark | |

| 2014 | World Championship[11] | Odense | Denmark | Australia | Canada | United States |

| 2013 | European Zone Championship | Antwerp | Belgium | Sweden | Denmark | Great Britain |

| 2012 | Paralympic Games | London | UK | Australia | Canada | United States |

| 2011 | European Zone Championship | Nottwil | Switzerland | Sweden | Great Britain | Belgium |

| 2010 | 5th World Championship[12] | Vancouver | Canada | United States | Australia | Japan |

| 2009 | 1st Americas Zone Championship | Buenos Aires | Argentina | United States | Canada | Argentina |

| Asia-Oceania Zone Championship | Christchurch | New Zealand | Australia | New Zealand | Japan | |

| 7th European Zone Championship | Hillerød | Denmark | Belgium | Sweden | Germany | |

| 2008 | Paralympic Games | Beijing | China | United States | Australia | Canada |

| 2007 | 4th Oceania Zone Championship | Sydney | Australia | Australia | Canada | New Zealand |

| 6th European Zone Championship | Espoo | Finland | Great Britain | Germany | Sweden | |

| 2006 | 4th World Championship[13] | Christchurch | New Zealand | United States | New Zealand | Canada |

| 2005 | 5th European Zone Championship | Middelfart | Denmark | Great Britain | Germany | Sweden |

| 3rd Oceania Zone Championship | Johannesburg | South Africa | New Zealand | Australia | Japan | |

| 2004 | Paralympic Games | Athens | Greece | New Zealand | Canada | United States |

| 2002 | 3rd World Championship | Gothenburg | Sweden | Canada | United States | Australia |

| 2000 | Paralympic Games | Sydney | Australia | United States | Australia | New Zealand |

| 1998 | 2nd World Championship | Toronto | Canada | United States | New Zealand | Canada |

| 1996 | Paralympic Games (demonstration) | Atlanta | United States | United States | Canada | New Zealand |

| 1995 | 1st World Championship | Nottwil | Switzerland | United States | Canada | New Zealand |

Popular culture

Wheelchair rugby was featured in the Oscar-nominated 2005 documentary Murderball. It was voted the #1 Top Sport Movie of all time by the movie review website Rotten Tomatoes.[14]

The character Jason Street in the NBC television show Friday Night Lights, having been paralyzed in a game of American football in the pilot, tries out for the United States quad rugby team in a later episode.

See also

- Wheelchair sports

- Wheelchair rugby league

- Wheelchair Australian rules football

Notes

- "History of Wheelchair Rugby", iwasf.com

- http://www.iwrf.com/?page=about_our_sport

- "Rugby", europaralympic.org/

- "Official IWRF Molten Wheelchair Rugby Balls", iwrf.com

- International Wheelchair Rugby Federation. "About Wheelchair Rugby". Archived from the original on 2008-04-24. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- "International Wheelchair Rugby Federation : IWRF Rankings". International Wheelchair Rugby Federation (IWRF). Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "TORONTO 2015 Parapan Am Games Footprint Announced".

- "2016 Paralympics Day 11 - Highlights". CNN. 2016-09-19. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- "Canadian wheelchair rugby team misses podium at 2016 Rio Paralympics". Comox Valley Record, Courtenay, British Columbia. 2016-09-18. Retrieved 2016-09-23.

- "Wheelchair Rugby - Schedule & Results".

- "2014 IWRF Wheelchair Rugby World Championship". 2014wrwc.dhif.dk. 2014-01-10. Retrieved 2015-11-09.

- Kingston, Gary (26 September 2010). "U.S. wins 2010 wheelchair rugby title in Richmond". The Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 26 September 2010.

- TVNZ, No title for Wheel Blacks, September 16, 2006. Retrieved September 21, 2008.

- Archived October 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

References

- International Wheelchair Rugby Federation, Technical Commission (2006), International Rules for the Sport of Wheelchair Rugby, archived from the original on 2006-08-25

- International Wheelchair Rugby Federation, Classification Commission (1999), International Wheelchair Rugby Classification Manual (2nd ed.), archived from the original on 2011-01-14

- International Wheelchair Rugby Federation (2006), About Wheelchair Rugby, archived from the original on 2008-04-24, retrieved August 2006 Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - International Paralympic Committee (2006), Wheelchair rugby: About the sport, archived from the original on 2006-03-07, retrieved August 2006 Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - Pasadena Texans Wheelchair Rugby (2007), Pasadena Texans Wheelchair Rugby, retrieved September 2007 Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help)

External links

- Official site of the International Wheelchair Rugby Federation (IWRF)

- Official site of the International Wheelchair and Amputee Sports Federation (IWAS)

- Official site of the International Paralympic Committee (IPC)

- Official site of the United States Quad Rugby Association (USQRA)

- Murderball on IMDb

- International wheelchair rugby links from the Canadian Wheelchair Sports Association