Diver propulsion vehicle

A diver propulsion vehicle (DPV), also known as an underwater propulsion vehicle or underwater scooter, or swimmer delivery vehicle (SDV) by armed forces, is an item of diving equipment used by scuba divers to increase range underwater. Range is restricted by the amount of breathing gas that can be carried, the rate at which that breathing gas is consumed, and the battery power of the DPV. Time limits imposed on the diver by decompression requirements may also limit safe range in practice. DPVs have recreational, scientific and military applications.

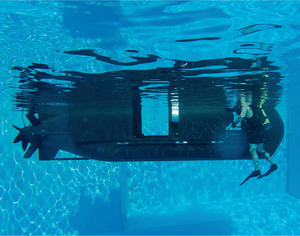

Recreational diver using a lightweight diver propulsion vehicle | |

| Acronym | DPV |

|---|---|

| Other names | Diver propulsion device, Underwater scooter |

| Uses | Reduce diver effort and increase speed and range during a dive |

DPVs include a range of configurations from small, easily portable scooter units with a small range and low speed, to faired or enclosed units capable of carrying several divers longer distances at higher speeds.

The earliest recorded DPVs were used for military purposes during World War II and were based on torpedo technology and components.

Structure

A DPV usually consists of a pressure-resistant watertight casing containing a battery-powered electric motor, which drives a propeller. The design must ensure that the propeller cannot harm the diver, diving equipment or marine life, the vehicle cannot be accidentally started or run away from the diver, and it remains approximately neutrally buoyant while in use underwater.

Application

DPVs are useful for extending the range of an autonomous diver that is otherwise restricted by the amount of breathing gas that can be carried, the rate at which that breathing gas is consumed, which is increased by exertion and diver fatigue, and the time limits imposed by decompression obligation, which depend on the dive profile.[1] Typical uses include cave diving and technical diving where the vehicles help move bulky equipment and make better use of the limited underwater time imposed by the decompression requirements of deep diving.[2] Military applications include delivery of combat divers and their equipment over distances or at speeds that would be otherwise impracticable.[3][4] There are accessories that can be mounted to a DPV to make it more useful, such as lights, compasses, and video cameras. Use of a DPV on deep dives can reduce the risk of hypercapnia from overexertion and high work of breathing.[5]

Limitations

DPV operation requires greater situational awareness than simply swimming, as some changes can happen much faster. Operating a DPV requires simultaneous depth control, buoyancy adjustment, monitoring of breathing gas, and navigation. Buoyancy control is vital for diver safety: The DPV has the capacity to dynamically compensate for poor buoyancy control by thrust vectoring while moving, but on stopping the diver may turn out to be dangerously positively or negatively buoyant if adjustments were not made to suit the changes in depth while moving. If the diver does not control the DPV properly, a rapid ascent or descent under power can result in barotrauma or decompression sickness.[6] High speed travel in confined spaces, or limited visibility can increase the risk of impact with the surroundings at speeds where injury and damage are more likely. Many forms of smaller marine life are very well camouflaged or hide well and are only seen by divers who move very slowly and look carefully. Fast movement and noise can frighten some fish into hiding or swimming away, and the DPV is bulky and affects precise maneuvering at close quarters. The DPV occupies at least one hand while in use and may get in the way while performing precision work like macro photography. Since the diver is not kicking for propulsion, they will generally get colder due to lower physical activity and increased water flow. This can be compensated by appropriate thermal insulation. If the operation of the DPV is critical to exit from a long penetration dive, it is necessary to allow for alternative propulsion in case of a breakdown to ensure safe exit before the breathing gas runs out. Control of the DPV is additional task loading and can distract the diver from other matters.[7] A DPV can increase the risk of a siltout if the thrust is allowed to wash over the bottom.[8]

History

Human torpedoes or manned torpedoes are a type of diver propulsion vehicle used as secret naval weapons in World War II. The name was commonly used to refer to the weapons that Italy, and later Britain, deployed in the Mediterranean and used to attack ships in enemy harbours.

The first human torpedo was the Italian Maiale ("Pig"). In operation, it was carried by another vessel (usually a normal submarine), and launched near the target. It was electrically propelled, with two crewmen in diving suits and rebreathers riding astride. They steered the torpedo at slow speed to the target, used the detachable warhead as a limpet mine and then rode the torpedo away.

The idea was successfully applied by the Italian navy (Regia Marina) early in World War II and then copied by the British when they discovered how effective this weapon could be was after three Italian units successfully penetrated the harbour of Alexandria and damaged the two British battleships HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Valiant, and the tanker "Sagona." The official Italian name for their craft was "Siluro a Lenta Corsa" (SLC or "Slow-running torpedo"), but the Italian operators nicknamed it "Maiale" after their inventor Teseo Tesei angrily called it a pig when it had been difficult to steer. The British versions were named "chariots".[9][10]

The Motorised Submersible Canoe (MSC), nicknamed Sleeping Beauty, was built by British Special Operations Executive (SOE) during World War II as an underwater vehicle for a single frogman to perform clandestine reconnaissance or attacks against enemy vessels.[11]

Types

Diver-tugs, tow-behind, scooters

The most common type of DPV tows the diver who holds onto handles on the stern or bow. Tow-behind scooters are most efficient by placing the diver parallel to and above the propeller wash. The diver wears a harness that includes a crotch-strap with a D-ring on the front of the strap. The scooter is rigged with a tow leash that clips to the scooter with releasable metal snap.

Swimmer delivery vehicles

Swimmer Delivery Vehicles (SDVs) are wet subs designed to transport frogmen from a combat swimmer unit or naval Special Forces underwater, over long distances. SDVs carry a pilot, co-pilot/navigator, and combat swimmer team and their equipment, to and from maritime mission objectives on land or at sea. The pilot and co-pilot are often a part of the swimmer team. An example of a modern SDV in use today is the SEAL Delivery Vehicle used by the United States Navy SEALs and British Special Boat Service.[12]

For long-range missions, SDVs can carry their own onboard breathing gas supply to extend the range of the swimmer's scuba equipment.[12]

SDVs are typically used to land special operations forces or plant limpet mines on the hull of enemy ships. In the former usage, they can land a combat swimmer team covertly on a hostile shore in order to conduct missions on land. After completing their mission, the team may return to the SDV to exfiltrate back to the mother-ship.[13] For extended missions on land, a team can be re-supplied by contact with other SDVs. In the latter usage, SDVs can stealthily plant mines and other bombs on ships or port infrastructure and then retreat to a safe distance before detonating the explosives.[14] In addition to destroying targets, the SDV can mislead enemies as to where they are being attacked from.[14] One type of SDV—the Mark 9 SEAL Delivery Vehicle—was also capable of firing torpedoes, giving it the standoff ability to attack from up to 3 nautical miles (5.6 km) away.[13]

The origins of the SDV stems from the Italian human torpedoes and the British Motorised Submersible Canoe used during World War II.[15]

Manned torpedoes

These are torpedo or fish-shaped vehicles for one or more divers typically sitting astride them or in hollows inside. The human torpedo was used to great effect by commando frogmen in World War II, who were able to sink more than 100,000 tons worth of ships in the Mediterranean alone.[16] Similar vehicles have been made for work divers or sport divers but better streamlined as these do not have warheads; the Dolphin made on the Isle of Wight (UK) in the 1971s is an example. Some Farallon and Aquazepp scooters are torpedo-shaped with handles near the bow and a raised seat at the rear to support the diver's crotch against the slipstream. The Russian Protei-5 and Proton carry the diver attached to the top. The New Zealand made Proteus is strapped onto the diver's cylinder.

Subskimmers

The Subskimmer is a submersible rigid-hulled inflatable boat (RIB). On the surface it is powered by a petrol engine, when submerged the petrol engine is sealed and it runs on battery-electric thrusters mounted on a steerable cross-arm. It can self inflate and deflate, transforming itself from a fast, light, surface boat to a submerged DPV. Started in the 1970s by Submarine Products Ltd. of Hexham, Northumberland, England, Subskimmer is now a tradename owned by Marine Specialised Technology.[17]

Wet subs

As DPVs get bigger they gradually merge into submarines. A wet sub is a small submarine where the crew spaces are flooded at ambient pressure and the crew must wear diving gear. Covert military operations use wet subs to deliver and retrieve operators into harbors and near-shore undetected.[13] An example is the Multi-Role Combatant Craft (MRCC).[18]

Towed sleds

These are unpowered boards (usually rectangular) towed by a surface boat which function as diving planes. The diver holds onto the sled and may use a quick-release tether to reduce fatigue. Depth control while submerged is by adjusting the angle of attack. Sometimes known as manta-boards, after the manta ray. Towed sleds are useful for surveys and searches in good visibility in waters where there are not too many large obstacles. The route is largely controlled by the towing vessel, but the diver has a limited amount of control over vertical and lateral excursions.[19]

Modern DPVs

DPVs currently in service include:

China

Divehead 1070 and Divehead 1500 [20] are two industrial grade DPVs, designed and developed by Lian Innovative [21] in China. Divehead is intended to fill the gap between military grade and recreational DPVs.

One of the DPVs in Chinese service is developed by the Kunming Wuwei Science & Technology Trade Co., Ltd[22] at Kunming, a solely owned subsidiary of Kunming 705th (Research) Institute Science & Technology Development Co. (昆明七零五所科技发展总公司))[23] at Kunming, which in turn, is a company wholly owned by the 705th Research Institute (headquartered in Xi'an) of the China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation. A total of 4 DPV models have been identified in Chinese naval service:[24]

- QY18 DPV[25]

- One man DPV/SDV weighing < 20 kg. Length: 0.8 m, diameter: 0.385 m, speed: 2 kn, endurance: > 1 hr, depth: 40 m.

- QY40 DPV[26]

- One man DPV/SDV weighing < 40 kg. Length: 1.2 m, diameter: 0.32 m, speed: 2 kn, endurance: > 1.5 hr, depth: 40 m.

- QX50 DPV[27]

- One man DPV/SDV weighing < 50 kg. Length: 1.6 m, diameter: 0.23 m, speed: 2 kn, endurance: > 2 hr, depth: 40 m.

- QJY-001 DPV[28]

- Two man DPV weighing < 90 kg. Length: < 2.3 m, diameter: < 0.53 m, max speed: 4 m/s, cruise speed: 2.7 kn for 1 person, 2 kn for 2 people, endurance: > 9 km at 2 kn, depth: 30 m, sea state: 3.

In addition to the DPVs currently in the Chinese naval inventory, Glory International Group Ltd[29] in Beijing is also marketing two of its DPVs, (GL602[30] and GL603[31]), to the Chinese military.

Italy

- Cosmos CE2F series such as CE2F/X100-T

- Two man DPV

Poland

- Błotniak

- One men DPV

Russia/USSR

- Protei-5 Russian diver propulsion vehicle

- One man DPV clipped on to the diver

- Sirena DPV[32]

- Sirena DPV is a Soviet human torpedo around 8 m long with 53 cm diameter so that it can be launched from torpedo tubes. Sirena DPV can transport two divers with a maximum range of 11 nmi at speed of 2-4 kn, with maximum depth of 40 m.[33]

- Project 907 Triton 1[34]

- Project 907 Triton 1 is a 1.6 t Soviet DPV manned by 2 crew riding astride spindle-shaped vehicle. The vehicle can rest on the sea bed for up to 10 days before being restarted again thus allowing great operational flexibility. Length is 5 m, beam and draft are both 1.4 m, and maximum depth is 40 m. The vehicle has a maximum range of 35 nmi with 6 hr endurance, and maximum speed is 6 kn.[35]

- Project 908 Triton 2[36]

- Project 908 Triton 2 is a 5.3 t Soviet DPV manned capable of carrying 6 crew. Although a wet sub, the design incorporates a system to maintain a constant pressure within the submarine regardless of depth. Length is 9.5 m, beam is 2.0 m and draft is 2.2 m, and maximum depth is 40 m. The vehicle has a maximum range of 60 nmi with 12 hr endurance, and maximum speed is 6 kn.[35]

Sweden

Swedish firm Defence Consulting Europe Aktiebolag (stock company, often abbreviated as DCE AB) has developed a family of SDV of modular design, all of them based on the same basic frame and general design principle, and current available versions include:[37]

- SEAL carrier[38]

- 2 men crew SDV with 30+ kn on surface and can be parked on the sea floor. There are three different modules for the Carrier providing different applications including: SEAL SDV – Swimmer Delivery Vehicle for SOP missions, SEAL AUV – Autonomous Under- water Vehicle for MCM missions, and SEAL RWSV – Remote Weapon Station Vehicle for Fire Support.[39]

- Smart SEAL

- A downsized SEAL Carrier, with 30+ kn on surface and can be parked on the sea floor.[40]

- Sub SEAL

- Electrically powered SEAL carrier capable of diving 40 m and carrying 6 divers with 600 liter of balanced load, with 30 nmi range at 5 kn. Can be mounted either inside the tube or transported on deck.[41]

United Arab Emirates

After purchasing US submersible manufacturer Seahorse Marine, Emirate Marine Technologies of United Arab Emirates has developed four classes DPV/SDV, all of them built of glass reinforced plastic and carbon composite materials:

- Class 4

- Three-ton two-man DPV using silver-zinc external battery packs to power an 8 kW motor. Sensor and control suites include a sonar, echo sounder, GPS, electronic compass and electronic mapping facility and an onboard computer. They have a range of 60 nmi (110 km) at 6 (maximum speed 7) kn and can operate down to 50 m. Maximum payload is 200 kg.[16]

- Class 5

- Eight-ton two-man DPV using nickel-cadmium external battery packs to power an 8 kW motor. All other specs are identical to Class 4 except the maximum payload is increased to 450 kg.[16]

- Class 6

- DPV/SDV currently under development to carry 4 or 8 (2 crew) divers. Will have 2 8 kW motors for underwater use and a diesel for surface operations. There will be computer-controlled system--including an automatic pilot to reduce operator workload, and a telescopic mast with a television camera and/or a thermal imager. Class 6 will have a range of 100 nmi (185 km) at 4 knots down to 50 m, but on the surface the diesel will give it a maximum speed of 20 kn. There will be built-in breathing sets for divers to conserve their underwater breathing apparatuses.[16]

- Class 8

- 11 m long DPV/SDV propelled by two eight-kW motors and powered by a lithium-ion battery for 6 divers (2 crew) currently under development. Maximum range is 50 nmi (93 km) at 5 kn with a maximum speed of 6 kn.[16]

United States

_prepares_to_launch_one_of_the_team's_SEAL_Delivery_Vehicles_(SDV)_from_the_back_of_the_Los_Angeles-class_attack_submarine_USS_Philadelphia_(SSN_690).jpg)

- Piranha[16]

- 1.63 t two-man DPV/SDV developed by Columbia Research Corporation built of fiber-glass. Maximum range is 27.5 nmi at 5 kn but burst speed of 8 kn can be achieved with its powerful brush-less DC motor and silver-zinc batteries. Maximum depth is 70 m, although it will usually be kept around 45 m.[44]

- SDV-X Dolphin

- 2.75 tonne 6 to 8-man SDV developed by Columbia Research Corporation built of fiberglass. Maximum range is 56.5 nmi (104.5 km) at 5 kn but burst speed of 8 kn can be achieved with its powerful brush-less DC motor and silver-zinc batteries. Maximum depth is 91 m, although it will usually be kept around 45 m.[44] Electronics include color liquid crystal displays and color digital charts, while the computer-based navigation system includes GPS and Doppler velocity log. There is also a multi-beam obstacle-avoidance sonar to distinguish targets while the integrated communications suite includes an underwater telephone and a VHF radio.[16]

- Sea Shadow SDV

- Developed by Anteon Corp, a wholly owned subsidiary of General Dynamics since 2006, the 107 kg Sea Shadow is for one or two crew and powered by lead-acid batteries.[45] The hull is of molded high-density polyethylene plastic to provide a low magnetic signature while folding bow planes and rotating motors allow the vehicle to be deployed through a 76-cm escape hatch. The Sea Shadow features electronic speed control with a manual back-up mode and an option of electronic drift compensation. Speed, depth, battery duration and voltage details is shown on a liquid crystal display, while there are visual warning signals on low battery power as well as unsafe rates of both ascent and descent. Sea Shadow has a range of 5 nmi (9.25 km) at 2 to 3 kn and at a maximum of depth of 30 m.[16]

- SEAL Delivery Vehicle (SDV)

- Mark 8 SDV with maximum speed of 6 knots (11 km/h) and maximum range of 36 nautical miles (66 km) at a depth of 6 metres. Currently in service with the US Navy[16]

- Shallow Water Combat Submersible

- The intended replacement to the SEAL Delivery Vehicle; has an endurance of 12 hours and can carry larger payloads over a greater distance than its predecessor.[46]

- Swimmer Delivery Vehicle

- Deployment of SDV

- Swimmer Transport Device[18]

Yugoslavia

All SDVs of former Yugoslavia were developed by Brodosplit - Brodogradilište Specijalnih Objekata d.o.o. which have been passed on to successor nations of former Yugoslavia.

- R-1

- 150 kg one-man torpedo like SDV with the operator straddling the aluminium alloy hull behind the first of two buoyancy tanks, and the operator can deliver 40 kg of limpet mines of either the 7 or 15 kg size. This SDV has a dimension of 3.72 metre (length) x 0.52 m (diameter) and can be housed in a submarine torpedo tube. The silver-zinc batteries operating a one-kW motor with a range of 8 kn (15 km) at 2.5 kn (maximum speed 3 kn) at a maximum depth of 60 m.[16]

- R-2 Mala[47]

- 1.41 t two-man SDV with crew ride astride spindle-shaped vehicle. The 4.5 kW DC electric motor is powered by either lead-acid or silver-zinc batteries, providing a maximum range of 23 nmi or 46 nmi. The cruise and maximum speed are 2.8 and 6.5 kn. Navigation equipment comprises an aircraft-type gyro compass, a magnetic compass, depth gauge with a 0 to 100-metre scale, echo-sounder, sonar, two searchlights and so on, all of which equipment is in a waterproof container. The R-2 can operate down to 60 metres with a maximum depth of 100m and a maximum limpet mine load of 250 kg.[16]

See also

- Cosmos CE2F series – Italian swimmer delivery vehicles

- Błotniak – A one-man wet cabin underwater craft designed in Poland in 1978

- Protei-5 Russian diver propulsion vehicle – Russian one-man diver propulsion vehicle

- Dive Xtras – A manufacturer of diver propulsion vehicles

- Chinese diver propulsion vehicles – Weapon systems of the naval branch of the People's Liberation Army of China

- SEAL Delivery Vehicle – Manned wet submersible for deploying Navy SEALS

- Advanced SEAL Delivery System – Former Navy SEAL mini-sub deployed from submarines

References

- Kimura, S; Cox, G; Carroll, J; Pengilley, S; Harmer, A (2012). "Going the Distance: Use of Diver Propulsion Units, Underwater Acoustic Navigation, and Three-Way Wireless Communication to Survey Kelp Forest Habitats". In: Steller D, Lobel L, Eds. Diving for Science 2012. Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences 31st Symposium. Dauphin Island, AL. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

- Kernagis Dawn N; McKinlay Casey; Kincaid Todd R (2008). "Dive Logistics of the Turner to Wakulla Cave Traverse". In: Brueggeman P, Pollock Neal W, Eds. Diving for Science 2008. Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences 27th Symposium. Dauphin Island, AL: AAUS;. Retrieved 2014-03-28.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- "Russia Special Forces use Germany-made diver propulsion vehicles in Mediterranean". Defence Blog: Online Military Magazine. September 10, 2018. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- "Diver Propulsion Device (DPD)". American Special Ops. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- Mitchell, Simon J. (August 2008). "4: Carbon dioxide retention". In Mount, Tom; Dituri, Joseph (eds.). Exploration and Mixed Gas Diving Encyclopedia (1st ed.). Miami Shores, Florida: International Association of Nitrox Divers. pp. 51–60. ISBN 978-0-915539-10-9.

- Rossier, Robert N. "Redefining Performance: Diver propulsion vehicles: Manage the risks, and enjoy the ride". Alert Diver. Divers Alert Network. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

- Mount, Tom (August 2008). "18: Psychological & Physical Fitness For Technical Diving". In Mount, Tom; Dituri, Joseph (eds.). Exploration and Mixed Gas Diving Encyclopedia (1st ed.). Miami Shores, Florida: International Association of Nitrox Divers. pp. 209–224. ISBN 978-0-915539-10-9.

- Citelli, Joe (August 2008). "24: The practical aspects of deep wreck diving". In Mount, Tom; Dituri, Joseph (eds.). Exploration and Mixed Gas Diving Encyclopedia (1st ed.). Miami Shores, Florida: International Association of Nitrox Divers. pp. 279–286. ISBN 978-0-915539-10-9.

- Polmar, Norman; Allen, Thomas B. (1996). World War II: the Encyclopedia of the War Years 1941-1945. New York: Random House. pp. 526. ISBN 0-486-47962-5.

- White, Michael (2015). Australian Submarines: A History. Victoria, Australia: Australian Teachers of Media. pp. 1152–1156. ISBN 978-1-876467-26-5.

- Rees, Quentin (2008). Cockleshell Canoes: British Military Canoes of World War Two. Most Secret. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84868-065-4.

- "SEAL Delivery Vehicles". National Navy UDT-SEAL Museum. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Sutton, H. I. (2016-05-05). Covert Shores: The Story of Naval Special Forces Missions and Minisubs (2nd ed.). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 9781533114877.

- Kelly, Orr (8 August 2017). Special Ops: Four Accounts of the Military's Elite Forces. Open Road Media. ISBN 9781504047456.

- Introduction to Naval Special Warfare Archived 2008-01-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Hooton, E. R. (December 1, 2005). "By sea & stealth: maritime special forces tend to arrive in hostile territory by sea and by stealth, but where once they would be delivered by rubber dinghies from a submarine now they are using Special Delivery Vehicles (SDV) and even midget submarines". Armada International. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- Sutton, H.I. (January 15, 2017). "SubSkimmer". Covert Shores. Retrieved November 21, 2019.

- "STIDD Military Submersibles". Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- Bass, D.K. (January 2003). "Crown-of-thorns starfish and coral surveys using the manta tow and scuba search techniques". Australian Institute of Marine Science – via Research Gate.

- industrial Diver propulsion vehicle accessed 18 June 2015

- http://lianinno.com/

- Kunming Wuwei Science & Technology Trade Co., Ltd (昆明五威科工贸有限公司) "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-01-08. Retrieved 2013-06-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) accessed 18 June 2013

- Kunming 705th (Research) Institute Science & Technology Development Co. (昆明七零五所科技发展总公司) http://kunming06165.11467.com/about.asp accessed 18 June 2013

- Sutton, H.I. (May 28, 2015). "Chinese Naval Special Forces projects and capabilities". Covert Shores. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- QY18 DPV "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-01-08. Retrieved 2013-06-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) accessed 18 June 2013

- QY40 DPV "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-01-08. Retrieved 2013-06-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) accessed 18 June 2013

- QX50 DPV "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-01-08. Retrieved 2013-06-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) accessed 18 June 2013

- QJY-001 DPV "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-01-08. Retrieved 2013-06-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) accessed 18 June 2013

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2013-06-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Glory International Group Ltd (格莱瑞国际集团有限公司)

- GL602 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-21. Retrieved 2013-06-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) accessed 18 June 2013

- GL603 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-12-14. Retrieved 2013-06-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) accessed 18 June 2013

- Eisenstadt, M (April 1994). Patrick Clawson (ed.). Iran's Strategic Intentions and Capabilities. An assessment of Iran's Military buildup, McNair Paper 29 (Report). Washington DC.: Institute for National Strategic Studies. p. 135. Retrieved 19 June 2013. citing Jane's Defence Monthly: 23. 20 March 1993

- Jane's Defence Weekly. IHS Inc.: 23 20 March 1993. ISSN 0265-3818

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-05-05. Retrieved 2013-06-17.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Project 907 Triton 1

- "Triton1/Triton2 Midget Submarines" (PDF). Naval Systems Export Catalogue. Moscow, Russia: Rososboronexport. p. 13. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- Kraskovsky, N. (2013-05-20). "Triton 2 V499". Shipspotting.com. Retrieved 2017-09-10.

- DCE SDVs Archived May 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- DCE SEAL carrier Archived November 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- DCE SEAL Carrier Archived May 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Smart SEAL Archived May 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Sub SEAL Archived May 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- DCE Torpedo SEAL Archived May 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Torpedo SEAL Archived May 26, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- "CRS DPVs/SDVs" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2005-11-03. Retrieved 2008-02-07.

- Sea Shadow SDV in Indonesian Archived June 25, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Page, Lewis (10 April 2009). "New Navy SEAL minisub's IT-system specs released". The Register. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- "R-2M Type Diver's Delivery Vessel". Zagreb, Croatia: Agencija Alan. 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2017.