Redundancy (engineering)

In engineering, redundancy is the duplication of critical components or functions of a system with the intention of increasing reliability of the system, usually in the form of a backup or fail-safe, or to improve actual system performance, such as in the case of GNSS receivers, or multi-threaded computer processing.

.jpg)

In many safety-critical systems, such as fly-by-wire and hydraulic systems in aircraft, some parts of the control system may be triplicated,[1] which is formally termed triple modular redundancy (TMR). An error in one component may then be out-voted by the other two. In a triply redundant system, the system has three sub components, all three of which must fail before the system fails. Since each one rarely fails, and the sub components are expected to fail independently, the probability of all three failing is calculated to be extraordinarily small; often outweighed by other risk factors, such as human error. Redundancy may also be known by the terms "majority voting systems"[2] or "voting logic".[3]

Redundancy sometimes produces less, instead of greater reliability – it creates a more complex system which is prone to various issues, it may lead to human neglect of duty, and may lead to higher production demands which by overstressing the system may make it less safe.[4]

Forms of redundancy

In computer science, there are four major forms of redundancy,[5] these are:

- Hardware redundancy, such as dual modular redundancy and triple modular redundancy

- Information redundancy, such as error detection and correction methods

- Time redundancy, performing the same operation multiple times such as multiple executions of a program or multiple copies of data transmitted

- Software redundancy such as N-version programming

A modified form of software redundancy, applied to hardware may be:

- Distinct functional redundancy, such as both mechanical and hydraulic braking in a car. Applied in the case of software, code written independently and distinctly different but producing the same results for the same inputs.

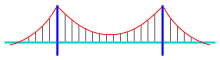

Structures are usually designed with redundant parts as well, ensuring that if one part fails, the entire structure will not collapse. A structure without redundancy is called fracture-critical, meaning that a single broken component can cause the collapse of the entire structure. Bridges that failed due to lack of redundancy include the Silver Bridge and the Interstate 5 bridge over the Skagit River.

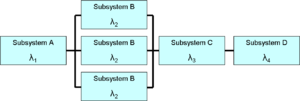

Parallel and combined systems demonstrate different level of redundancy. The models are subject of studies in reliability and safety engineering.

Function of redundancy

The two functions of redundancy are passive redundancy and active redundancy. Both functions prevent performance decline from exceeding specification limits without human intervention using extra capacity.

Passive redundancy uses excess capacity to reduce the impact of component failures. One common form of passive redundancy is the extra strength of cabling and struts used in bridges. This extra strength allows some structural components to fail without bridge collapse. The extra strength used in the design is called the margin of safety.

Eyes and ears provide working examples of passive redundancy. Vision loss in one eye does not cause blindness but depth perception is impaired. Hearing loss in one ear does not cause deafness but directionality is lost. Performance decline is commonly associated with passive redundancy when a limited number of failures occur.

Active redundancy eliminates performance declines by monitoring the performance of individual devices, and this monitoring is used in voting logic. The voting logic is linked to switching that automatically reconfigures the components. Error detection and correction and the Global Positioning System (GPS) are two examples of active redundancy.

Electrical power distribution provides an example of active redundancy. Several power lines connect each generation facility with customers. Each power line includes monitors that detect overload. Each power line also includes circuit breakers. The combination of power lines provides excess capacity. Circuit breakers disconnect a power line when monitors detect an overload. Power is redistributed across the remaining lines.

Disadvantages

Charles Perrow, author of Normal Accidents, has said that sometimes redundancies backfire and produce less, not more reliability. This may happen in three ways: First, redundant safety devices result in a more complex system, more prone to errors and accidents. Second, redundancy may lead to shirking of responsibility among workers. Third, redundancy may lead to increased production pressures, resulting in a system that operates at higher speeds, but less safely.[4]

Voting logic

Voting logic uses performance monitoring to determine how to reconfigure individual components so that operation continues without violating specification limitations of the overall system. Voting logic often involves computers, but systems composed of items other than computers may be reconfigured using voting logic. Circuit breakers are an example of a form of non-computer voting logic.

Electrical power systems use power scheduling to reconfigure active redundancy. Computing systems adjust the production output of each generating facility when other generating facilities are suddenly lost. This prevents blackout conditions during major events such as an earthquake.

The simplest voting logic in computing systems involves two components: primary and alternate. They both run similar software, but the output from the alternate remains inactive during normal operation. The primary monitors itself and periodically sends an activity message to the alternate as long as everything is OK. All outputs from the primary stop, including the activity message, when the primary detects a fault. The alternate activates its output and takes over from the primary after a brief delay when the activity message ceases. Errors in voting logic can cause both outputs to be active or inactive at the same time, or cause outputs to flutter on and off.

A more reliable form of voting logic involves an odd number of three devices or more. All perform identical functions and the outputs are compared by the voting logic. The voting logic establishes a majority when there is a disagreement, and the majority will act to deactivate the output from other device(s) that disagree. A single fault will not interrupt normal operation. This technique is used with avionics systems, such as those responsible for operation of the Space Shuttle.

Calculating the probability of system failure

Each duplicate component added to the system decreases the probability of system failure according to the formula:-

where:

- – number of components

- – probability of component i failing

- – the probability of all components failing (system failure)

This formula assumes independence of failure events. That means that the probability of a component B failing given that a component A has already failed is the same as that of B failing when A has not failed. There are situations where this is unreasonable, such as using two power supplies connected to the same socket in such a way that if one power supply failed, the other would too.

It also assumes that only one component is needed to keep the system running.

See also

- Degeneracy

- Common cause and special cause (statistics)

- Data redundancy

- Double switching

- Fault tolerance – Resilience of systems to component failures or errors

- Radiation hardening – Processes and techniques used for making electronic devices resistant to ionizing radiation

- Factor of safety – Factor by which an engineered system's capacity is higher than the expected load to ensure safety in case of error or uncertainty

- Reliability engineering – Sub-discipline of systems engineering that emphasizes dependability in the lifecycle management of a product or a system

- Reliability theory of aging and longevity

- Safety engineering – Engineering discipline which assures that engineered systems provide acceptable levels of safety

- Reliability (computer networking)

- MTBF

- N+1 redundancy

References

- Redundancy Management Technique for Space Shuttle Computers (PDF), IBM Research

- R. Jayapal (2003-12-04). "Analog Voting Circuit Is More Flexible Than Its Digital Version". elecdesign.com. Archived from the original on 2007-03-03. Retrieved 2014-06-01.

- "The Aerospace Corporation | Assuring Space Mission Success". Aero.org. 2014-05-20. Retrieved 2014-06-01.

- Scott D. Sagan (March 2004). "Learning from Normal Accidents" (PDF). Organization & Environment. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-07-14.

- Koren, Israel; Krishna, C. Mani (2007). Fault-Tolerant Systems. San Francisco, CA: Morgan Kaufmann. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-12-088525-1.

- Kokcharov I. Structural Safety http://www.kokch.kts.ru/me/t6/SIA_6_Structural_Safety.pdf

External links

- Secure Propulsion using Advanced Redundant Control

- Using powerline as a redundant communication channel

- Flammini, Francesco; Marrone, Stefano; Mazzocca, Nicola; Vittorini, Valeria (2009). "A new modeling approach to the safety evaluation of N-modular redundant computer systems in presence of imperfect maintenance". Reliability Engineering & System Safety. 94 (9): 1422–1432. arXiv:1304.6656. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2009.02.014.