Inca Empire

The Inca Empire (Quechua: Tawantinsuyu, lit. "The Four Regions"[3]), also known as the Incan Empire and the Inka Empire, was the largest empire in pre-Columbian America.[4] The administrative, political and military center of the empire was located in the city of Cusco. The Inca civilization arose from the Peruvian highlands sometime in the early 13th century. Its last stronghold was conquered by the Spanish in 1572.

Realm of the Four Parts Tawantinsuyu (Quechua) | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1438–1533 | |||||||||||||||||||||

Reconstructed banner of the Sapa Inca | |||||||||||||||||||||

.svg.png) The Inca Empire at its greatest extent ca. 1525 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Cusco (1438–1533) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Quechua | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Aymara, Puquina, Jaqi family, Muchik and scores of smaller languages. | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Inca religion | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Divine, absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Sapa Inca | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1438–1471 | Pachacuti | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1471–1493 | Túpac Inca Yupanqui | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1493–1527 | Huayna Capac | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1527–1532 | Huáscar | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1532–1533 | Atahualpa | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Pre-Columbian era | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Pachacuti created the Tawantinsuyu | 1438 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1529–1532 | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Spanish conquest led by Francisco Pizarro | 1533 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• End of the last Inca resistance | 1572 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1527[1][2] | 2,000,000 km2 (770,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1527 | 10,000,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||||||||||||

From 1438 to 1533, the Incas incorporated a large portion of western South America, centered on the Andean Mountains, using conquest and peaceful assimilation, among other methods. At its largest, the empire joined Peru, western Ecuador, western and south central Bolivia, northwest Argentina, a large portion of what is today Chile, and the southwesternmost tip of Colombia into a state comparable to the historical empires of Eurasia. Its official language was Quechua.[5] Many local forms of worship persisted in the empire, most of them concerning local sacred Huacas, but the Inca leadership encouraged the sun worship of Inti – their sun god – and imposed its sovereignty above other cults such as that of Pachamama.[6] The Incas considered their king, the Sapa Inca, to be the "son of the sun."[7]

The Inca Empire was unusual in that it lacked many features associated with civilization in the Old World. Anthropologist Gordon McEwan wrote that:[8]

The Incas lacked the use of wheeled vehicles. They lacked animals to ride and draft animals that could pull wagons and plows... [They] lacked the knowledge of iron and steel... Above all, they lacked a system of writing... Despite these supposed handicaps, the Incas were still able to construct one of the greatest imperial states in human history.

— Gordon McEwan, The Incas: New Perspectives

Notable features of the Inca Empire include its monumental architecture, especially stonework, extensive road network reaching all corners of the empire, finely-woven textiles, use of knotted strings (quipu) for record keeping and communication, agricultural innovations in a difficult environment, and the organization and management fostered or imposed on its people and their labor.

The Incan economy has been described in contradictory ways by scholars:[9]

... feudal, slave, socialist (here one may choose between socialist paradise or socialist tyranny)

— Darrell E. La Lone, The Inca as a Nonmarket Economy: Supply on Command versus Supply and Demand

The Inca Empire functioned largely without money and without markets. Instead, exchange of goods and services was based on reciprocity between individuals and among individuals, groups, and Inca rulers. "Taxes" consisted of a labour obligation of a person to the Empire. The Inca rulers (who theoretically owned all the means of production) reciprocated by granting access to land and goods and providing food and drink in celebratory feasts for their subjects.[10]

Etymology

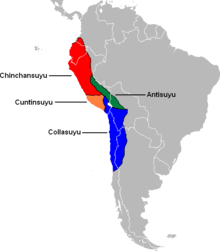

The Inca referred to their empire as Tawantinsuyu,[3] "the four suyu". In Quechua, tawa is four and -ntin is a suffix naming a group, so that a tawantin is a quartet, a group of four things taken together, in this case the four suyu ("regions" or "provinces") whose corners met at the capital. The four suyu were: Chinchaysuyu (north), Antisuyu (east; the Amazon jungle), Qullasuyu (south) and Kuntisuyu (west). The name Tawantinsuyu was, therefore, a descriptive term indicating a union of provinces. The Spanish transliterated the name as Tahuatinsuyo or Tahuatinsuyu.

The term Inka means "ruler" or "lord" in Quechua and was used to refer to the ruling class or the ruling family.[11] The Incas were a very small percentage of the total population of the empire, probably numbering only 15,000 to 40,000, but ruling a population of around 10 million people.[12] The Spanish adopted the term (transliterated as Inca in Spanish) as an ethnic term referring to all subjects of the empire rather than simply the ruling class. As such, the name Imperio inca ("Inca Empire") referred to the nation that they encountered and subsequently conquered.

History

Antecedents

The Inca Empire was the last chapter of thousands of years of Andean civilizations. The Andean civilization was one of five civilizations in the world deemed by scholars to be "pristine", that is indigenous and not derivative from other civilizations.[13]

The Inca Empire was preceded by two large-scale empires in the Andes: the Tiwanaku (c. 300–1100 AD), based around Lake Titicaca and the Wari or Huari (c. 600–1100 AD) centered near the city of Ayacucho. The Wari occupied the Cuzco area for about 400 years. Thus, many of the characteristics of the Inca Empire derived from earlier multi-ethnic and expansive Andean cultures.[14]

Carl Troll has argued that the development of the Inca state in the central Andes was aided by conditions that allow for the elaboration of the staple food chuño. Chuño, which can be stored for long periods, is made of potato dried at the freezing temperatures that are common at nighttime in the southern Peruvian highlands. Such a link between the Inca state and chuño may be questioned, as potatoes and other crops such as maize can also be dried with only sunlight.[15] Troll did also argue that llamas, the Inca's pack animal, can be found in its largest numbers in this very same region.[15] It is worth considering the maximum extent of the Inca Empire roughly coincided with the greatest distribution of llamas and alpacas in Pre-Hispanic America.[16] The link between the Andean biomes of puna and páramo, pastoralism and the Inca state is a matter of research.[17] As a third point Troll pointed out irrigation technology as advantageous to the Inca state-building.[17] While Troll theorized environmental influences on the Inca Empire, he opposed environmental determinism, arguing that culture lay at the core of the Inca civilization.[17]

Origin

The Inca people were a pastoral tribe in the Cusco area around the 12th century. Incan oral history tells an origin story of three caves. The center cave at Tampu T'uqu (Tambo Tocco) was named Qhapaq T'uqu ("principal niche", also spelled Capac Tocco). The other caves were Maras T'uqu (Maras Tocco) and Sutiq T'uqu (Sutic Tocco).[18] Four brothers and four sisters stepped out of the middle cave. They were: Ayar Manco, Ayar Cachi, Ayar Awqa (Ayar Auca) and Ayar Uchu; and Mama Ocllo, Mama Raua, Mama Huaco and Mama Qura (Mama Cora). Out of the side caves came the people who were to be the ancestors of all the Inca clans.

Ayar Manco carried a magic staff made of the finest gold. Where this staff landed, the people would live. They traveled for a long time. On the way, Ayar Cachi boasted about his strength and power. His siblings tricked him into returning to the cave to get a sacred llama. When he went into the cave, they trapped him inside to get rid of him.

Ayar Uchu decided to stay on the top of the cave to look over the Inca people. The minute he proclaimed that, he turned to stone. They built a shrine around the stone and it became a sacred object. Ayar Auca grew tired of all this and decided to travel alone. Only Ayar Manco and his four sisters remained.

Finally, they reached Cusco. The staff sank into the ground. Before they arrived, Mama Ocllo had already borne Ayar Manco a child, Sinchi Roca. The people who were already living in Cusco fought hard to keep their land, but Mama Huaca was a good fighter. When the enemy attacked, she threw her bolas (several stones tied together that spun through the air when thrown) at a soldier (gualla) and killed him instantly. The other people became afraid and ran away.

After that, Ayar Manco became known as Manco Cápac, the founder of the Inca. It is said that he and his sisters built the first Inca homes in the valley with their own hands. When the time came, Manco Cápac turned to stone like his brothers before him. His son, Sinchi Roca, became the second emperor of the Inca.[19]

Kingdom of Cusco

Under the leadership of Manco Cápac, the Inca formed the small city-state Kingdom of Cusco (Quechua Qusqu', Qosqo). In 1438, they began a far-reaching expansion under the command of Sapa Inca (paramount leader) Pachacuti-Cusi Yupanqui, whose name literally meant "earth-shaker". The name of Pachacuti was given to him after he conquered the Tribe of Chancas (modern Apurímac). During his reign, he and his son Tupac Yupanqui brought much of the modern-day territory of Peru under Inca control.[20]

Reorganization and formation

Pachacuti reorganized the kingdom of Cusco into the Tahuantinsuyu, which consisted of a central government with the Inca at its head and four provincial governments with strong leaders: Chinchasuyu (NW), Antisuyu (NE), Kuntisuyu (SW) and Qullasuyu (SE).[21] Pachacuti is thought to have built Machu Picchu, either as a family home or summer retreat, although it may have been an agricultural station.[22]

Pachacuti sent spies to regions he wanted in his empire and they brought to him reports on political organization, military strength and wealth. He then sent messages to their leaders extolling the benefits of joining his empire, offering them presents of luxury goods such as high quality textiles and promising that they would be materially richer as his subjects.

Most accepted the rule of the Inca as a fait accompli and acquiesced peacefully. Refusal to accept Inca rule resulted in military conquest. Following conquest the local rulers were executed. The ruler's children were brought to Cusco to learn about Inca administration systems, then return to rule their native lands. This allowed the Inca to indoctrinate them into the Inca nobility and, with luck, marry their daughters into families at various corners of the empire.

Expansion and consolidation

Traditionally the son of the Inca ruler led the army. Pachacuti's son Túpac Inca Yupanqui began conquests to the north in 1463 and continued them as Inca ruler after Pachacuti's death in 1471. Túpac Inca's most important conquest was the Kingdom of Chimor, the Inca's only serious rival for the Peruvian coast. Túpac Inca's empire then stretched north into modern-day Ecuador and Colombia.

Túpac Inca's son Huayna Cápac added a small portion of land to the north in modern-day Ecuador. At its height, the Inca Empire included Peru, western and south central Bolivia, southwest Ecuador and a large portion of what is today Chile, north of the Maule River. Traditional historiography claims the advance south halted after the Battle of the Maule where they met determined resistance from the Mapuche.[23] This view is challenged by historian Osvaldo Silva who argues instead that it was the social and political framework of the Mapuche that posed the main difficulty in imposing imperial rule.[23] Silva does accept that the battle of the Maule was a stalemate, but argues the Incas lacked incentives for conquest they had had when fighting more complex societies such as the Chimú Empire.[23] Silva also disputes the date given by traditional historiography for the battle: the late 15th century during the reign of Topa Inca Yupanqui (1471–93).[23] Instead, he places it in 1532 during the Inca Civil War.[23] Nevertheless, Silva agrees on the claim that the bulk of the Incan conquests were made during the late 15th century.[23] At the time of the Incan Civil War an Inca army was, according to Diego de Rosales, subduing a revolt among the Diaguitas of Copiapó and Coquimbo.[23]

The empire's push into the Amazon Basin near the Chinchipe River was stopped by the Shuar in 1527.[24] The empire extended into corners of Argentina and Colombia. However, most of the southern portion of the Inca empire, the portion denominated as Qullasuyu, was located in the Altiplano.

The Inca Empire was an amalgamation of languages, cultures and peoples. The components of the empire were not all uniformly loyal, nor were the local cultures all fully integrated. The Inca empire as a whole had an economy based on exchange and taxation of luxury goods and labour. The following quote describes a method of taxation:

For as is well known to all, not a single village of the highlands or the plains failed to pay the tribute levied on it by those who were in charge of these matters. There were even provinces where, when the natives alleged that they were unable to pay their tribute, the Inca ordered that each inhabitant should be obliged to turn in every four months a large quill full of live lice, which was the Inca's way of teaching and accustoming them to pay tribute.[25]

Inca Civil War and Spanish conquest

Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro and his brothers explored south from what is today Panama, reaching Inca territory by 1526.[26] It was clear that they had reached a wealthy land with prospects of great treasure, and after another expedition in 1529 Pizarro traveled to Spain and received royal approval to conquer the region and be its viceroy. This approval was received as detailed in the following quote: "In July 1529 the Queen of Spain signed a charter allowing Pizarro to conquer the Incas. Pizarro was named governor and captain of all conquests in Peru, or New Castile, as the Spanish now called the land."[27]

When the conquistadors returned to Peru in 1532, a war of succession between the sons of Sapa Inca Huayna Capac, Huáscar and Atahualpa, and unrest among newly conquered territories weakened the empire. Perhaps more importantly, smallpox, influenza, typhus and measles had spread from Central America.

The forces led by Pizarro consisted of 168 men, one cannon, and 27 horses. Conquistadors ported lances, arquebuses, steel armor and long swords. In contrast, the Inca used weapons made out of wood, stone, copper and bronze, while using an Alpaca fiber based armor, putting them at significant technological disadvantage—none of their weapons could pierce the Spanish steel armor. In addition, due to the absence of horses in the Americas, the Inca did not develop tactics to fight cavalry. However, the Inca were still effective warriors, being able to successfully fight the Mapuche, which later would strategically defeat the Spanish as they expanded further south.

The first engagement between the Inca and the Spanish was the Battle of Puná, near present-day Guayaquil, Ecuador, on the Pacific Coast; Pizarro then founded the city of Piura in July 1532. Hernando de Soto was sent inland to explore the interior and returned with an invitation to meet the Inca, Atahualpa, who had defeated his brother in the civil war and was resting at Cajamarca with his army of 80,000 troops, that were at the moment armed only with hunting tools (knives and lassos for hunting llamas).

Pizarro and some of his men, most notably a friar named Vincente de Valverde, met with the Inca, who had brought only a small retinue. The Inca offered them ceremonial chicha in a golden cup, which the Spanish rejected. The Spanish interpreter, Friar Vincente, read the "Requerimiento" that demanded that he and his empire accept the rule of King Charles I of Spain and convert to Christianity. Atahualpa dismissed the message and asked them to leave. After this, the Spanish began their attack against the mostly unarmed Inca, captured Atahualpa as hostage, and forced the Inca to collaborate.

Atahualpa offered the Spaniards enough gold to fill the room he was imprisoned in and twice that amount of silver. The Inca fulfilled this ransom, but Pizarro deceived them, refusing to release the Inca afterwards. During Atahualpa's imprisonment Huáscar was assassinated elsewhere. The Spaniards maintained that this was at Atahualpa's orders; this was used as one of the charges against Atahualpa when the Spaniards finally executed him, in August 1533.[28]

Although "defeat" often implies an unwanted loss in battle, much of the Inca elite "actually welcomed the Spanish invaders as liberators and willingly settled down with them to share rule of Andean farmers and miners."[29]

Last Incas

.jpg)

The Spanish installed Atahualpa's brother Manco Inca Yupanqui in power; for some time Manco cooperated with the Spanish while they fought to put down resistance in the north. Meanwhile, an associate of Pizarro, Diego de Almagro, attempted to claim Cusco. Manco tried to use this intra-Spanish feud to his advantage, recapturing Cusco in 1536, but the Spanish retook the city afterwards. Manco Inca then retreated to the mountains of Vilcabamba and established the small Neo-Inca State, where he and his successors ruled for another 36 years, sometimes raiding the Spanish or inciting revolts against them. In 1572 the last Inca stronghold was conquered and the last ruler, Túpac Amaru, Manco's son, was captured and executed.[30] This ended resistance to the Spanish conquest under the political authority of the Inca state.

After the fall of the Inca Empire many aspects of Inca culture were systematically destroyed, including their sophisticated farming system, known as the vertical archipelago model of agriculture.[31] Spanish colonial officials used the Inca mita corvée labor system for colonial aims, sometimes brutally. One member of each family was forced to work in the gold and silver mines, the foremost of which was the titanic silver mine at Potosí. When a family member died, which would usually happen within a year or two, the family was required to send a replacement.

The effects of smallpox on the Inca empire were even more devastating. Beginning in Colombia, smallpox spread rapidly before the Spanish invaders first arrived in the empire. The spread was probably aided by the efficient Inca road system. Smallpox was only the first epidemic.[32] Other diseases, including a probable Typhus outbreak in 1546, influenza and smallpox together in 1558, smallpox again in 1589, diphtheria in 1614, and measles in 1618, all ravaged the Inca people.

Society

Population

The number of people inhabiting Tawantinsuyu at its peak is uncertain, with estimates ranging from 4–37 million. Most population estimates are in the range of 6 to 14 million. In spite of the fact that the Inca kept excellent census records using their quipus, knowledge of how to read them was lost as almost all fell into disuse and disintegrated over time or were destroyed by the Spaniards.[33]

Languages

The empire was extremely linguistically diverse. Some of the most important languages were Quechua, Aymara, Puquina and Mochica, respectively mainly spoken in the Central Andes, the Altiplano or (Qullasuyu), the south Peruvian coast (Kuntisuyu), and the area of the north Peruvian coast (Chinchaysuyu) around Chan Chan, today Trujillo. Other languages included Quignam, Jaqaru, Leco, Uru-Chipaya languages, Kunza, Humahuaca, Cacán, Mapudungun, Culle, Chachapoya, Catacao languages, Manta, and Barbacoan languages, as well as numerous Amazonian languages on the frontier regions. The exact linguistic topography of the pre-Columbian and early colonial Andes remains incompletely understood, owing to the extinction of several languages and the loss of historical records.

In order to manage this diversity, the Inca lords promoted the usage of Quechua, especially the variety of modern-day Lima [34] as the Qhapaq Runasimi ("great language of the people"), or the official language/lingua franca. Defined by mutual intelligibility, Quechua is actually a family of languages rather than one single language, parallel to the Romance or Slavic languages in Europe. Most communities within the empire, even those resistant to Inca rule, learned to speak a variety of Quechua (forming new regional varieties with distinct phonetics) in order to communicate with the Inca lords and mitma colonists, as well as the wider integrating society, but largely retained their native languages as well. The Incas also had their own ethnic language, referred to as Qhapaq simi ("royal language"), which is thought to have been closely related to or a dialect of Puquina, which appears to have been the official language of the former Tiwanaku Empire, from which the Incas claimed descent, making Qhapaq simi a source of prestige for them. The split between Qhapaq simi and Qhapaq Runasimi also exemplifies the larger split between hatun and hunin (high and low) society in general.

There are several common misconceptions about the history of Quechua, as it is frequently identified as the "Inca language". Quechua did not originate with the Incas, had been a lingua franca in multiple areas before the Inca expansions, was diverse before the rise of the Incas, and it was not the native or original language of the Incas. In addition, the main official language of the Inca Empire was the coastal Quechua variety, native to modern Lima, not the Cusco dialect. The pre-Inca Chincha Kingdom, with whom the Incas struck an alliance, had made this variety into a local prestige language by their extensive trading activities. The Peruvian coast was also the most populous and economically active region of the Inca Empire, and employing coastal Quechua offered an alternative to neighboring Mochica, the language of the rival state of Chimu. Trade had also been spreading Quechua northwards before the Inca expansions, towards Cajamarca and Ecuador, and was likely the official language of the older Wari Empire. However, the Incas have left an impressive linguistic legacy, in that they introduced Quechua to many areas where it is still widely spoken today, including Ecuador, southern Bolivia, southern Colombia, and parts of the Amazon basin. The Spanish conquerors continued the official usage of Quechua during the early colonial period, and transformed it into a literary language.[35]

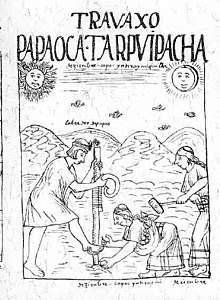

The Incas were not known to develop a written form of language; however, they visually recorded narratives through paintings on vases and cups (qirus).[36] These paintings are usually accompanied by geometric patterns known as toqapu, which are also found in textiles. Researchers have speculated that toqapu patterns could have served as a form of written communication (e.g.: heraldry, or glyphs), however this remains unclear.[37] The Incas also kept records by using quipus.

Age and defining gender

The high infant mortality rates that plagued the Inca Empire caused all newborn infants to be given the term ‘wawa’ when they were born. Most families did not invest very much into their child until they reached the age of two or three years old. Once the child reached the age of three, a "coming of age" ceremony occurred, called the rutuchikuy. For the Incas, this ceremony indicated that the child had entered the stage of "ignorance". During this ceremony, the family would invite all relatives to their house for food and dance, and then each member of the family would receive a lock of hair from the child. After each family member had received a lock, the father would shave the child's head. This stage of life was categorized by a stage of "ignorance, inexperience, and lack of reason, a condition that the child would overcome with time."[38] For Incan society, in order to advance from the stage of ignorance to development the child must learn the roles associated with their gender.

The next important ritual was to celebrate the maturity of a child. Unlike the coming of age ceremony, the celebration of maturity signified the child's sexual potency. This celebration of puberty was called warachikuy for boys and qikuchikuy for girls. The warachikuy ceremony included dancing, fasting, tasks to display strength, and family ceremonies. The boy would also be given new clothes and taught how to act as an unmarried man. The qikuchikuy signified the onset of menstruation, upon which the girl would go into the forest alone and return only once the bleeding had ended. In the forest she would fast, and, once returned, the girl would be given a new name, adult clothing, and advice. This "folly" stage of life was the time young adults were allowed to have sex without being a parent.[38]

Between the ages of 20 and 30, people were considered young adults, "ripe for serious thought and labor."[38] Young adults were able to retain their youthful status by living at home and assisting in their home community. Young adults only reached full maturity and independence once they had married.

At the end of life, the terms for men and women denote loss of sexual vitality and humanity. Specifically, the "decrepitude" stage signifies the loss of mental well-being and further physical decline.

| Table 7.1 from R. Alan Covey's Article[38] | |||

| Age | Social Value of Life Stage | Female Term | Male Term |

| < 3 | Conception | Wawa | Wawa |

| 3–7 | Ignorance (not speaking) | Warma | Warma |

| 7–14 | Development | Thaski (or P'asña) | Maqt'a |

| 14–20 | Folly (sexually active) | Sipas (unmarried) | Wayna (unmarried) |

| 20+ | Maturity (body and mind) | Warmi | Qhari |

| 70 | Infirmity | Paya | Machu |

| 90 | Decrepitude | Ruku | Ruku |

Marriage

In the Incan Empire, the age of marriage differed for men and women: men typically married at the age of 20, while women usually got married about four years earlier at the age of 16.[39] Men who were highly ranked in society could have multiple wives, but those lower in the ranks could only take a single wife.[40] Marriages were typically within classes and resembled a more business-like agreement. Once married, the women were expected to cook, collect food and watch over the children and livestock.[39] Girls and mothers would also work around the house to keep it orderly to please the public inspectors.[41] These duties remained the same even after wives became pregnant and with the added responsibility of praying and making offerings to Kanopa, who was the god of pregnancy.[39] It was typical for marriages to begin on a trial basis with both men and women having a say in the longevity of the marriage. If the man felt that it wouldn't work out or if the woman wanted to return to her parents’ home the marriage would end. Once the marriage was final, the only way the two could be divorced was if they did not have a child together.[39] Marriage within the Empire was crucial for survival. A family was considered disadvantaged if there was not a married couple at the center because everyday life centered around the balance of male and female tasks.[42]

Gender roles

According to some historians, such as Terence N. D'Altroy, male and female roles were considered equal in Inca society. The "indigenous cultures saw the two genders as complementary parts of a whole."[42] In other words, there was not a hierarchical structure in the domestic sphere for the Incas. Within the domestic sphere, women were known as the weavers. Women's everyday tasks included: spinning, watching the children, weaving cloth, cooking, brewing chichi, preparing fields for cultivation, planting seeds, bearing children, harvesting, weeding, hoeing, herding, and carrying water.[43] Men on the other hand, "weeded, plowed, participated in combat, helped in the harvest, carried firewood, built houses, herded llama and alpaca, and spun and wove when necessary".[43] This relationship between the genders may have been complementary. Unsurprisingly, onlooking Spaniards believed women were treated like slaves, because women did not work in Spanish society to the same extent, and certainly did not work in fields.[44] Women were sometimes allowed to own land and herds because inheritance was passed down from both the mother's and father's side of the family.[45] Kinship within the Inca society followed a parallel line of descent. In other words, women ascended from women and men ascended from men. Due to the parallel descent, a woman had access to land and other necessities through her mother.[43]

Religion

Inca myths were transmitted orally until early Spanish colonists recorded them; however, some scholars claim that they were recorded on quipus, Andean knotted string records.[46]

The Inca believed in reincarnation.[47] After death, the passage to the next world was fraught with difficulties. The spirit of the dead, camaquen, would need to follow a long road and during the trip the assistance of a black dog that could see in the dark was required. Most Incas imagined the after world to be like an earthly paradise with flower-covered fields and snow-capped mountains.

It was important to the Inca that they not die as a result of burning or that the body of the deceased not be incinerated. Burning would cause their vital force to disappear and threaten their passage to the after world. Those who obeyed the Inca moral code – ama suwa, ama llulla, ama quella (do not steal, do not lie, do not be lazy) – "went to live in the Sun's warmth while others spent their eternal days in the cold earth".[48] The Inca nobility practiced cranial deformation.[49] They wrapped tight cloth straps around the heads of newborns to shape their soft skulls into a more conical form, thus distinguishing the nobility from other social classes.

The Incas made human sacrifices. As many as 4,000 servants, court officials, favorites and concubines were killed upon the death of the Inca Huayna Capac in 1527.[50] The Incas performed child sacrifices around important events, such as the death of the Sapa Inca or during a famine. These sacrifices were known as qhapaq hucha.[51]

Deities

The Incas were polytheists who worshipped many gods. These included:

- Viracocha (also Pachacamac) – Created all living things

- Apu Illapu – Rain God, prayed to when they need rain

- Ayar Cachi – Hot-tempered God, causes earthquakes

- Illapa – Goddess of lightning and thunder (also Yakumama water goddess)

- Inti – sun god and patron deity of the holy city of Cusco (home of the sun)

- Kuychi – Rainbow God, connected with fertility

- Mama Killa – Wife of Inti, called Moon Mother

- Mama Occlo – Wisdom to civilize the people, taught women to weave cloth and build houses

- Manco Cápac – known for his courage and sent to earth to become first king of the Incas. Taught people how to grow plants, make weapons, work together, share resources and worship the Gods

- Pachamama – The Goddess of earth and wife of Viracocha. People give her offerings of coca leaves and beer and pray to her for major agricultural occasions

- Quchamama – Goddess of the sea

- Sachamama – Means Mother Tree, goddess in the shape of a snake with two heads

- Yakumama – Means mother Water. Represented as a snake. When she came to earth she transformed into a great river (also Illapa).

Economy

The Inca Empire employed central planning. The Inca Empire traded with outside regions, although they did not operate a substantial internal market economy. While axe-monies were used along the northern coast, presumably by the provincial mindaláe trading class,[52] most households in the empire lived in a traditional economy in which households were required to pay taxes, usually in the form of the mit'a corvée labor, and military obligations,[53] though barter (or trueque) was present in some areas.[54] In return, the state provided security, food in times of hardship through the supply of emergency resources, agricultural projects (e.g. aqueducts and terraces) to increase productivity and occasional feasts. While mit'a was used by the state to obtain labor, individual villages had a pre-inca system of communal work, known as mink'a. This system survives to the modern day, known as mink'a or faena. The economy rested on the material foundations of the vertical archipelago, a system of ecological complementarity in accessing resources[55] and the cultural foundation of ayni, or reciprocal exchange.[56][57]

Government

Beliefs

The Sapa Inca was conceptualized as divine and was effectively head of the state religion. The Willaq Umu (or Chief Priest) was second to the emperor. Local religious traditions continued and in some cases such as the Oracle at Pachacamac on the Peruvian coast, were officially venerated. Following Pachacuti, the Sapa Inca claimed descent from Inti, who placed a high value on imperial blood; by the end of the empire, it was common to incestuously wed brother and sister. He was "son of the sun," and his people the intip churin, or "children of the sun," and both his right to rule and mission to conquer derived from his holy ancestor. The Sapa Inca also presided over ideologically important festivals, notably during the Inti Raymi, or "Sunfest" attended by soldiers, mummified rulers, nobles, clerics and the general population of Cusco beginning on the June solstice and culminating nine days later with the ritual breaking of the earth using a foot plow by the Inca. Moreover, Cusco was considered cosmologically central, loaded as it was with huacas and radiating ceque lines and geographic center of the Four-Quarters; Inca Garcilaso de la Vega called it "the navel of the universe".[58][59][60][61]

Organization of the empire

The Inca Empire was a federalist system consisting of a central government with the Inca at its head and four-quarters, or suyu: Chinchay Suyu (NW), Anti Suyu (NE), Kunti Suyu (SW) and Qulla Suyu (SE). The four corners of these quarters met at the center, Cusco. These suyu were likely created around 1460 during the reign of Pachacuti before the empire reached its largest territorial extent. At the time the suyu were established they were roughly of equal size and only later changed their proportions as the empire expanded north and south along the Andes.[62]

Cusco was likely not organized as a wamani, or province. Rather, it was probably somewhat akin to a modern federal district, like Washington, DC or Mexico City. The city sat at the center of the four suyu and served as the preeminent center of politics and religion. While Cusco was essentially governed by the Sapa Inca, his relatives and the royal panaqa lineages, each suyu was governed by an Apu, a term of esteem used for men of high status and for venerated mountains. Both Cusco as a district and the four suyu as administrative regions were grouped into upper hanan and lower hurin divisions. As the Inca did not have written records, it is impossible to exhaustively list the constituent wamani. However, colonial records allow us to reconstruct a partial list. There were likely more than 86 wamani, with more than 48 in the highlands and more than 38 on the coast.[63][64][65]

Suyu

The most populous suyu was Chinchaysuyu, which encompassed the former Chimu empire and much of the northern Andes. At its largest extent, it extended through much of modern Ecuador and into modern Colombia.

The largest suyu by area was Qullasuyu, named after the Aymara-speaking Qulla people. It encompassed the Bolivian Altiplano and much of the southern Andes, reaching Argentina and as far south as the Maipo or Maule river in Central Chile.[66] Historian José Bengoa singled out Quillota as likely being the foremost Inca settlement in Chile.[67]

The second smallest suyu, Antisuyu, was northwest of Cusco in the high Andes. Its name is the root of the word "Andes."[68]

Kuntisuyu was the smallest suyu, located along the southern coast of modern Peru, extending into the highlands towards Cusco.[69]

Laws

The Inca state had no separate judiciary or codified laws. Customs, expectations and traditional local power holders governed behavior. The state had legal force, such as through tokoyrikoq (lit. "he who sees all"), or inspectors. The highest such inspector, typically a blood relative to the Sapa Inca, acted independently of the conventional hierarchy, providing a point of view for the Sapa Inca free of bureaucratic influence.[70]

The Inca had three moral precepts that governed their behavior:

- Ama sua: Do not steal

- Ama llulla: Do not lie

- Ama quella: Do not be lazy

Administration

Colonial sources are not entirely clear or in agreement about Inca government structure, such as exact duties and functions of government positions. But the basic structure can be broadly described. The top was the Sapa Inca. Below that may have been the Willaq Umu, literally the "priest who recounts", the High Priest of the Sun.[71] However, beneath the Sapa Inca also sat the Inkap rantin, who was a confidant and assistant to the Sapa Inca, perhaps similar to a Prime Minister.[72] Starting with Topa Inca Yupanqui, a "Council of the Realm" was composed of 16 nobles: 2 from hanan Cusco; 2 from hurin Cusco; 4 from Chinchaysuyu; 2 from Cuntisuyu; 4 from Collasuyu; and 2 from Antisuyu. This weighting of representation balanced the hanan and hurin divisions of the empire, both within Cusco and within the Quarters (hanan suyukuna and hurin suyukuna).[73]

While provincial bureaucracy and government varied greatly, the basic organization was decimal. Taxpayers – male heads of household of a certain age range – were organized into corvée labor units (often doubling as military units) that formed the state's muscle as part of mit'a service. Each unit of more than 100 tax-payers were headed by a kuraka, while smaller units were headed by a kamayuq, a lower, non-hereditary status. However, while kuraka status was hereditary and typically served for life, the position of a kuraka in the hierarchy was subject to change based on the privileges of superiors in the hierarchy; a pachaka kuraka could be appointed to the position by a waranqa kuraka. Furthermore, one kuraka in each decimal level could serve as the head of one of the nine groups at a lower level, so that a pachaka kuraka might also be a waranqa kuraka, in effect directly responsible for one unit of 100 tax-payers and less directly responsible for nine other such units.[74][75][76]

| Kuraka in Charge[77][78] | Number of Taxpayers |

|---|---|

| Hunu kuraka | 10,000 |

| Pichkawaranqa kuraka | 5,000 |

| Waranqa kuraka | 1,000 |

| Pichkapachaka kuraka | 500 |

| Pachaka kuraka | 100 |

| Pichkachunka kamayuq | 50 |

| Chunka kamayuq | 10 |

Arts and technology

Monumental architecture

Architecture was the most important of the Incan arts, with textiles reflecting architectural motifs. The most notable example is Machu Picchu, which was constructed by Inca engineers. The prime Inca structures were made of stone blocks that fit together so well that a knife could not be fitted through the stonework. These constructs have survived for centuries, with no use of mortar to sustain them.

This process was first used on a large scale by the Pucara (c. 300 BC–AD 300) peoples to the south in Lake Titicaca and later in the city of Tiwanaku (c. AD 400–1100) in present-day Bolivia. The rocks were sculpted to fit together exactly by repeatedly lowering a rock onto another and carving away any sections on the lower rock where the dust was compressed. The tight fit and the concavity on the lower rocks made them extraordinarily stable, despite the ongoing challenge of earthquakes and volcanic activity.

Measures, calendrics and mathematics

Physical measures used by the Inca were based on human body parts. Units included fingers, the distance from thumb to forefinger, palms, cubits and wingspans. The most basic distance unit was thatkiy or thatki, or one pace. The next largest unit was reported by Cobo to be the topo or tupu, measuring 6,000 thatkiys, or about 7.7 km (4.8 mi); careful study has shown that a range of 4.0 to 6.3 km (2.5 to 3.9 mi) is likely. Next was the wamani, composed of 30 topos (roughly 232 km or 144 mi). To measure area, 25 by 50 wingspans were used, reckoned in topos (roughly 3,280 km2 or 1,270 sq mi). It seems likely that distance was often interpreted as one day's walk; the distance between tambo way-stations varies widely in terms of distance, but far less in terms of time to walk that distance.[79][80]

Inca calendars were strongly tied to astronomy. Inca astronomers understood equinoxes, solstices and zenith passages, along with the Venus cycle. They could not, however, predict eclipses. The Inca calendar was essentially lunisolar, as two calendars were maintained in parallel, one solar and one lunar. As 12 lunar months fall 11 days short of a full 365-day solar year, those in charge of the calendar had to adjust every winter solstice. Each lunar month was marked with festivals and rituals.[81] Apparently, the days of the week were not named and days were not grouped into weeks. Similarly, months were not grouped into seasons. Time during a day was not measured in hours or minutes, but in terms of how far the sun had travelled or in how long it had taken to perform a task.[82]

The sophistication of Inca administration, calendrics and engineering required facility with numbers. Numerical information was stored in the knots of quipu strings, allowing for compact storage of large numbers.[83][84] These numbers were stored in base-10 digits, the same base used by the Quechua language[85] and in administrative and military units.[75] These numbers, stored in quipu, could be calculated on yupanas, grids with squares of positionally varying mathematical values, perhaps functioning as an abacus.[86] Calculation was facilitated by moving piles of tokens, seeds or pebbles between compartments of the yupana. It is likely that Inca mathematics at least allowed division of integers into integers or fractions and multiplication of integers and fractions.[87]

According to mid-17th-century Jesuit chronicler Bernabé Cobo,[88] the Inca designated officials to perform accounting-related tasks. These officials were called quipo camayos. Study of khipu sample VA 42527 (Museum für Völkerkunde, Berlin)[89] revealed that the numbers arranged in calendrically significant patterns were used for agricultural purposes in the "farm account books" kept by the khipukamayuq (accountant or warehouse keeper) to facilitate the closing of accounting books.[90]

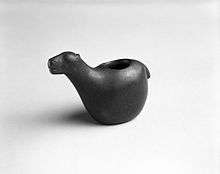

Ceramics, precious metals and textiles

Ceramics were painted using the polychrome technique portraying numerous motifs including animals, birds, waves, felines (popular in the Chavin culture) and geometric patterns found in the Nazca style of ceramics. In a culture without a written language, ceramics portrayed the basic scenes of everyday life, including the smelting of metals, relationships and scenes of tribal warfare. The most distinctive Inca ceramic objects are the Cusco bottles or "aryballos".[91] Many of these pieces are on display in Lima in the Larco Archaeological Museum and the National Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology and History.

Almost all of the gold and silver work of the Incan empire was melted down by the conquistadors, and shipped back to Spain.[92]

Communication and medicine

The Inca recorded information on assemblages of knotted strings, known as Quipu, although they can no longer be decoded. Originally it was thought that Quipu were used only as mnemonic devices or to record numerical data. Quipus are also believed to record history and literature.[93]

The Inca made many discoveries in medicine.[94] They performed successful skull surgery, by cutting holes in the skull to alleviate fluid buildup and inflammation caused by head wounds. Many skull surgeries performed by Inca surgeons were successful. Survival rates were 80–90%, compared to about 30% before Inca times.[95]

Coca

The Incas revered the coca plant as sacred/magical. Its leaves were used in moderate amounts to lessen hunger and pain during work, but were mostly used for religious and health purposes.[96] The Spaniards took advantage of the effects of chewing coca leaves.[96] The Chasqui, messengers who ran throughout the empire to deliver messages, chewed coca leaves for extra energy. Coca leaves were also used as an anaesthetic during surgeries.

Weapons, armor and warfare

The Inca army was the most powerful at that time, because any ordinary villager or farmer could be recruited as a soldier as part of the mit'a system of mandatory public service. Every able bodied male Inca of fighting age had to take part in war in some capacity at least once and to prepare for warfare again when needed. By the time the empire reached its largest size, every section of the empire contributed in setting up an army for war.

The Incas had no iron or steel and their weapons were not much more effective than those of their opponents so they often defeated opponents by sheer force of numbers, or else by persuading them to surrender beforehand by offering generous terms.[97] Inca weaponry included "hardwood spears launched using throwers, arrows, javelins, slings, the bolas, clubs, and maces with star-shaped heads made of copper or bronze."[97][98] Rolling rocks downhill onto the enemy was a common strategy, taking advantage of the hilly terrain.[99] Fighting was sometimes accompanied by drums and trumpets made of wood, shell or bone.[100][101] Armor included:[97][102]

- Helmets made of wood, cane, or animal skin, often lined with copper or bronze; some were adorned with feathers

- Round or square shields made from wood or hide

- Cloth tunics padded with cotton and small wooden planks to protect the spine

- Ceremonial metal breastplates, of copper, silver, and gold, have been found in burial sites, some of which may have also been used in battle.[103][104]

Roads allowed quick movement (on foot) for the Inca army and shelters called tambo and storage silos called qullqas were built one day's travelling distance from each other, so that an army on campaign could always be fed and rested. This can be seen in names of ruins such as Ollantay Tambo, or My Lord's Storehouse. These were set up so the Inca and his entourage would always have supplies (and possibly shelter) ready as they traveled.

Banner of the Inca

Chronicles and references from the 16th and 17th centuries support the idea of a banner. However, it represented the Inca (emperor), not the empire.

Francisco López de Jerez[105] wrote in 1534:

... todos venían repartidos en sus escuadras con sus banderas y capitanes que los mandan, con tanto concierto como turcos.

(... all of them came distributed into squads, with their flags and captains commanding them, as well-ordered as Turks.)

Chronicler Bernabé Cobo wrote:

The royal standard or banner was a small square flag, ten or twelve spans around, made of cotton or wool cloth, placed on the end of a long staff, stretched and stiff such that it did not wave in the air and on it each king painted his arms and emblems, for each one chose different ones, though the sign of the Incas was the rainbow and two parallel snakes along the width with the tassel as a crown, which each king used to add for a badge or blazon those preferred, like a lion, an eagle and other figures.

(... el guión o estandarte real era una banderilla cuadrada y pequeña, de diez o doce palmos de ruedo, hecha de lienzo de algodón o de lana, iba puesta en el remate de una asta larga, tendida y tiesa, sin que ondease al aire, y en ella pintaba cada rey sus armas y divisas, porque cada uno las escogía diferentes, aunque las generales de los Incas eran el arco celeste y dos culebras tendidas a lo largo paralelas con la borda que le servía de corona, a las cuales solía añadir por divisa y blasón cada rey las que le parecía, como un león, un águila y otras figuras.)

-Bernabé Cobo, Historia del Nuevo Mundo (1653)

Guaman Poma's 1615 book, El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, shows numerous line drawings of Inca flags.[106] In his 1847 book A History of the Conquest of Peru, "William H. Prescott ... says that in the Inca army each company had its particular banner and that the imperial standard, high above all, displayed the glittering device of the rainbow, the armorial ensign of the Incas."[107] A 1917 world flags book says the Inca "heir-apparent ... was entitled to display the royal standard of the rainbow in his military campaigns."[108]

In modern times the rainbow flag has been wrongly associated with the Tawantinsuyu and displayed as a symbol of Inca heritage by some groups in Peru and Bolivia. The city of Cusco also flies the Rainbow Flag, but as an official flag of the city. The Peruvian president Alejandro Toledo (2001–2006) flew the Rainbow Flag in Lima's presidential palace. However, according to Peruvian historiography, the Inca Empire never had a flag. Peruvian historian María Rostworowski said, "I bet my life, the Inca never had that flag, it never existed, no chronicler mentioned it".[109] Also, to the Peruvian newspaper El Comercio, the flag dates to the first decades of the 20th century,[110] and even the Congress of the Republic of Peru has determined that flag is a fake by citing the conclusion of National Academy of Peruvian History:

"The official use of the wrongly called 'Tawantinsuyu flag' is a mistake. In the Pre-Hispanic Andean World there did not exist the concept of a flag, it did not belong to their historic context".[110]

National Academy of Peruvian History

Adaptations to altitude

Incas were able to adapt to their high-altitude living through successful acclimatization, which is characterized by increasing oxygen supply to the blood tissues. For the native Inca living in the Andean highlands, this was achieved through the development of a larger lung capacity, and an increase in red blood cell counts, hemoglobin concentration, and capillary beds.[111]

Compared to other humans, the Incas had slower heart rates, almost one-third larger lung capacity, about 2 L (4 pints) more blood volume and double the amount of hemoglobin, which transfers oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body. While the Conquistadors may have been slightly taller, the Inca had the advantage of coping with the extraordinary altitude.

See also

Important Incan archeological sites

Incan-related

- Aclla, the "chosen women"

- Amauta, Inca teachers

- Amazonas before the Inca Empire

- Anden, agricultural terrace

- Chincha culture

- Inca Civil War

- Inca cuisine

- Incan agriculture

- Incan aqueducts

- Incas in Central Chile

- Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala

- Inca Garcilaso de la Vega (chronicler)

- Paria, Bolivia

- Quipu, knotted cords

- Qullqa, Inca storehouse

- Religion in the Inca Empire

- Spanish conquest of Peru

- Tambo

- Tampukancha, Inca religious site

- Society of the Spanish-Americans in the Spanish Colonial Americas

General

- Ancient Peru

- Cultural periods of Peru

- Demographic history of the indigenous peoples of the Americas

- History of Peru

- History of smallpox

- Muisca Confederation

Notes

- Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 497. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- McEwan 2008, p. 221.

- Schwartz, Glenn M.; Nichols, John J. (2010). After Collapse: The Regeneration of Complex Societies. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-2936-0.

- "Quechua, the Language of the Incas". 11 November 2013.

- "The Inca – All Empires".

- "The Inca." The National Foreign Language Center at the University of Maryland. 29 May 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- McEwan, Gordon F. (2006). The Incas: New Perspectives. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. p. 5.

- La Lone, Darrell E. "The Inca as a Nonmarket Economy: Supply on Command versus Supply and Demand". p. 292. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- Morris, Craig and von Hagen, Adrianna (2011), The Incas, London: Thames & Hudson, pp. 48–58

- "Inca". American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Company. 2009.

- McEwan 2008, p. 93.

- Upton, Gary and von Hagen, Adriana (2015), Encyclopedia of the Incas, New York: Rowand & Littlefield, p. 2. Some scholars cite 6 or 7 pristine civilizations.

- McEwan, Gordon F. (2006), The Incas: New Perspectives, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, p. 65

- Gade, Daniel (2016). "Urubamba Verticality: Reflections on Crops and Diseases". Spell of the Urubamba: Anthropogeographical Essays on an Andean Valley in Space and Time. p. 86. ISBN 978-3-319-20849-7.

- Hardoy, Jorge Henríque (1973). Pre-Columbian Cities. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8027-0380-4.

- Gade, Daniel W. (1996). "Carl Troll on Nature and Culture in the Andes (Carl Troll über die Natur und Kultur in den Anden)". Erdkunde. 50 (4): 301–16.

- McEwan 2008, p. 57.

- McEwan 2008, p. 69.

- Demarest, Arthur Andrew; Conrad, Geoffrey W. (1984). Religion and Empire: The Dynamics of Aztec and Inca Expansionism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 57–59. ISBN 0-521-31896-3.

- The three laws of Tawantinsuyu are still referred to in Bolivia these days as the three laws of the Qullasuyu.

- Weatherford, J. McIver (1988). Indian Givers: How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the World. New York: Fawcett Columbine. pp. 60–62. ISBN 0-449-90496-2.

- Silva Galdames, Osvaldo (1983). "¿Detuvo la batalla del Maule la expansión inca hacia el sur de Chile?". Cuadernos de Historia (in Spanish). 3: 7–25. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- Ernesto Salazar (1977). An Indian federation in lowland Ecuador (PDF). International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. p. 13. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- Starn, Orin; Kirk, Carlos Iván; Degregori, Carlos Iván (2009). The Peru Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-8750-3.

-

- Juan de Samano (9 October 2009). "Relacion de los primeros descubrimientos de Francisco Pizarro y Diego de Almagro, 1526". bloknot.info (A. Skromnitsky). Retrieved 10 October 2009.

- Somervill, Barbara (2005). Francisco Pizarro: Conqueror of the Incas. Compass Point Books. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-7565-1061-9.

- McEwan 2008, p. 79.

- Raudzens, George, ed. (2003). Technology, Disease, and Colonial Conquest. Boston: Brill Academic. p. xiv.

- McEwan 2008, p. 31.

- Sanderson 1992, p. 76.

- Millersville University Silent Killers of the New World Archived 3 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- McEwan 2008, pp. 93–96. The 10 million population estimate in the info box is a mid-range estimate of the population..

- Torero Fernández de Córdoba, Alfredo. (1970) "Lingüística e historia de la Sociedad Andina", Anales Científicos de la Universidad Agraria, VIII, 3-4, págs. 249-251. Lima: UNALM.

- "Origins And Diversity of Quechua".

- "Comparing chronicles and Andean visual texts. Issues for analysis" (PDF). Chungara, Revista de Antropología Chilena. 46, Nº 1, 2014: 91–113.

- "Royal Tocapu in Guacan Poma: An Inca Heraldic?". Boletin de Arqueologia PUCP. Nº 8, 2004: 305–23.

- Covey, R. Alan. "Inca Gender Relations: from household to empire.” Gender in cross-cultural perspective. Brettell, Caroline; Sargent, Carolyn F., 1947 (Seventh edition ed.). Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 978-0-415-78386-6. OCLC 962171839.

- Incas : lords of gold and glory. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books. 1992. ISBN 0-8094-9870-7. OCLC 25371192.

- Gouda, F. (2008). Colonial Encounters, Body Politics, and Flows of Desire. Journal of Women's History, 20(3), 166–80.

- Gerard, K. (1997). Ancient Lives. New Moon, 4(4), 44.

- N., D'Altroy, Terence (2002). The Incas. Malden, MA: Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-17677-2. OCLC 46449340.

- Irene., Silverblatt (1987). Moon, sun, and witches : gender ideologies and class in Inca and colonial Peru. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-07726-6. OCLC 14165734.

- 1580–1657., Cobo, Bernabé (1979). History of the Inca Empire : an account of the Indians' customs and their origin, together with a treatise on Inca legends, history, and social institutions. Hamilton, Roland. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-73008-X. OCLC 4933087.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Andrew., Malpass, Michael (1996). Daily life in the Inca empire. Westport, CN: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-29390-2. OCLC 33405288.

- Urton, Gary (2009). Signs of the Inka Khipu: Binary Coding in the Andean Knotted-String Records. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-77375-2.

- The Incas of Peru

- "Inca moral code | Heart of the Initiate – Shamanic Retreats". www.heartoftheinitiate.com. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Burger, Richard L.; Salazar, Lucy C. (2004). Machu Picchu: Unveiling the Mystery of the Incas. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09763-4.

- Davies, Nigel (1981). Human sacrifice: in history and today. Morrow. pp. 261–62. ISBN 978-0-688-03755-0.

- Reinhard, Johan (November 1999). "A 6,700 metros niños incas sacrificados quedaron congelados en el tiempo". National Geographic, Spanish version: 36–55.

- Salomon, Frank (1 January 1987). "A North Andean Status Trader Complex under Inka Rule". Ethnohistory. 34 (1): 63–77. doi:10.2307/482266. JSTOR 482266.

- Earls, J. The Character of Inca and Andean Agriculture. pp. 1–29

- Moseley 2001, p. 44.

- Murra, John V.; Rowe, John Howland (1 January 1984). "An Interview with John V. Murra". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 64 (4): 633–53. doi:10.2307/2514748. JSTOR 2514748.

- Maffie, J. (5 March 2013). "Pre-Columbian Philosophies". In Nuccetelli, Susana; Schutte, Ofelia; Bueno, Otávio (eds.). A Companion to Latin American Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 137–38. ISBN 978-1-118-61056-5.

- Newitz, Annalee (3 January 2012), The greatest mystery of the Inca Empire was its strange economy, io9, retrieved 4 January 2012

- Willey, Gordon R. (1966). An Introduction to American Archaeology: South America. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. pp. 173–75.

- D'Altroy 2014, pp. 86–89, 111, 154–55.

- Moseley2001, pp. 81–85.

- McEwan 2008, pp. 138–39.

- Rowe in Steward, Ed., p. 262

- Rowe in Steward, ed., pp. 185–92

- D'Altroy 2014, pp. 42–43, 86–89.

- McEwan 2008, pp. 113–14.

- Dillehay, T.; Gordon, A. (1998). "La actividad prehispánica y su influencia en la Araucanía". In Dillehay, Tom; Netherly, Patricia (eds.). La frontera del estado Inca. Editorial Abya Yala. ISBN 978-9978-04-977-8.

- Bengoa 2003, pp. 37–38.

- D'Altroy 2014, p. 87.

- D'Altroy 2014, pp. 87–88.

- D'Altroy 2014, pp. 235–36.

- D'Altroy 2014, p. 99.

- R. T. Zuidema, Hierarchy and Space in Incaic Social Organization. Ethnohistory, Vol. 30, No. 2. (Spring, 1983), p. 97

- Zuidema 1983, p. 48.

- Julien 1982, pp. 121–27.

- D'Altroy 2014, pp. 233–34.

- McEwan 2008, pp. 114–15.

- Julien 1982, p. 123.

- D'Altroy 2014, p. 233.

- D'Altroy 2014, pp. 246–47.

- McEwan 2008, pp. 179–80.

- D'Altroy 2014, pp. 150–54.

- McEwan 2008, pp. 185–87.

- Neuman, William (2 January 2016). "Untangling an Accounting Tool and an Ancient Incan Mystery". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- McEwan 2008, p. 183-185.

- "Supplementary Information for: Heggarty 2008". Arch.cam.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- "Inca mathematics". History.mcs.st-and.ac.uk. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- McEwan 2008, p. 185.

- Cobo, B. (1983 [1653]). Obras del P. Bernabé Cobo. Vol. 1. Edited and preliminary study By Francisco Mateos. Biblioteca de Autores Españoles, vol. 91. Madrid: Ediciones Atlas.

- Sáez-Rodríguez, A. (2012). "An Ethnomathematics Exercise for Analyzing a Khipu Sample from Pachacamac (Perú)". Revista Latinoamericana de Etnomatemática. 5 (1): 62–88.

- Sáez-Rodríguez, A. (2013). "Knot numbers used as labels for identifying subject matter of a khipu". Revista Latinoamericana de Etnomatemática. 6 (1): 4–19.

- Berrin, Kathleen (1997). The Spirit of Ancient Peru: Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-01802-6.

- Minster, Christopher; PhD. "What Happened to the Treasure Hoard of the Inca Emperor?". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- McEwan 2008, p. 183.

- Somervill, Barbara A. (2005). Empire of the Inca. New York: Facts on File, Inc. pp. 101–03. ISBN 0-8160-5560-2.

- "Incan skull surgery". Science News.

- "Cocaine's use: From the Incas to the U.S." Boca Raton News. 4 April 1985. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Cartwright, Mark (19 May 2016). "Inca Warfare". Ancient History Encyclopedia.

- Kim MacQuarrie (17 June 2008). The Last Days of the Incas. Simon and Schuster. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-7432-6050-3.

- Geoffrey Parker (29 September 2008). The Cambridge Illustrated History of Warfare: The Triumph of the West. Cambridge University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-521-73806-4.

- Robert Stevenson (1 January 1968). Music in Aztec & Inca Territory. University of California Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-520-03169-2.

- Father Bernabe Cobo; Roland Hamilton (1 May 1990). Inca Religion and Customs. University of Texas Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-292-73861-4.

- Cottie Arthur Burland (1968). Peru Under the Incas. Putnam. p. 101.

The sling was the most deadly projectile weapon. Spear, long-handled axe and bronze-headed mace were the effective weapons. Protection was afforded by a wooden helmet covered with bronze, long quilted tunic and flexible quilted shield.

- Peter Von Sivers; Charles Desnoyers; George B. Stow (2012). Patterns of World History. Oxford University Press. p. 505. ISBN 978-0-19-533334-3.

- Maestro, Carmen Pérez (1999). "Armas de metal en el Perú prehispánico". Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, Señe I, Prehistoria y Arqueología (in Spanish): 319–346.

- Francisco López de Jerez,Verdadera relación de la conquista del Peru y provincia de Cusco, llamada la Nueva Castilla, 1534.

- Guaman Poma, El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, (1615/1616), pp. 256, 286, 344, 346, 400, 434, 1077, this pagination corresponds to the Det Kongelige Bibliotek search engine pagination of the book. Additionally Poma shows both well drafted European flags and coats of arms on pp. 373, 515, 558, 1077. On pp. 83, 167–71 Poma uses a European heraldic graphic convention, a shield, to place certain totems related to Inca leaders.

- Preble, George Henry; Charles Edward Asnis (1917). Origin and History of the American Flag and of the Naval and Yacht-Club Signals... 1. N. L. Brown. p. 85.

- McCandless, Byron (1917). Flags of the world. National Geographic Society. p. 356.

- "¿Bandera gay o del Tahuantinsuyo?". Terra. 19 April 2010.

- "La Bandera del Tahuantisuyo" (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 12 June 2009.

- Frisancho, A. Roberto (2013), "Developmental Functional Adaptation to High Altitude: Review" (PDF), American Journal of Human Biology, 25 (2): 151–68, doi:10.1002/ajhb.22367, hdl:2027.42/96751, PMID 24065360

References

| Library resources about Inca Empire |

- Куприенко, Сергей (2013). Источники XVI–XVII веков по истории инков: хроники, документы, письма. Kyiv: Видавець Купрієнко СА. ISBN 978-617-7085-03-3.

- Bengoa, José (2003). Historia de los antiguos mapuches del sur: desde antes de la llegada de los españoles hasta las paces de Quilín : siglos XVI y XVII. BPR Publishers. ISBN 978-956-8303-02-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- de la Vega, Garcilaso (2006). The Royal Commentaries of the Incas and General History of Peru, Abridged. Hackett Publishing. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-1-60384-856-5.

- Hemming, John (2003). The Conquest of the Incas. Harvest Press. ISBN 0-15-602826-3.

- MacQuarrie, Kim (2007). The Last Days of the Incas. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-6049-7.

- Mann, Charles C. (2005). 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Knopf. pp. 64–105. ISBN 978-0-307-27818-0.

- McEwan, Gordon F. (2008). The Incas: New Perspectives. W.W. Norton, Incorporated. pp. 221–. ISBN 978-0-393-33301-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morales, Edmundo (1995). The guinea pig: healing, food, and ritual in the Andes. University of Arizona Press.

- Popenoe, Hugh; Steven R. King; Jorge Leon; Luis Sumar Kalinowski; Noel D. Vietmeyer (1989). Lost Crops of the Incas: Little-Known Plants of the Andes with Promise for Worldwide Cultivation. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. ISBN 0-309-04264-X.

- Sanderson, Steven E. (1992). The Politics of Trade in Latin American Development. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2021-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- D'Altroy, Terence N. (2014). The Incas. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-61059-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Steward, Julian H., ed. (1946). The Handbook of South American Indians: The Andean Civilizations. no. 143 v. 2 Bulletin / Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. Biodiversity Heritage Library / Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. p. 1935.

- Julien, Catherine J. (1982). Inca Decimal Administration in the Lake Titicaca Region in The Inca and Aztec States: 1400–1800. New York: Academic Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moseley, Michael Edward (2001). The Incas and Their Ancestors: The Archaeology of Peru. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28277-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- "Guaman Poma – El Primer Nueva Corónica Y Buen Gobierno" – A high-quality digital version of the Corónica, scanned from the original manuscript.

- Conquest nts.html Inca Land by Hiram Bingham (published 1912–1922).

- Inca Artifacts, Peru and Machu Picchu 360-degree movies of inca artifacts and Peruvian landscapes.

- Ancient Civilizations – Inca

- "Ice Treasures of the Inca" National Geographic site.

- "The Sacred Hymns of Pachacutec," poetry of an Inca emperor.

- Incan Religion

- Engineering in the Andes Mountains, lecture on Inca suspension bridges

- A Map and Timeline of Inca Empire events

- Ancient Peruvian art: contributions to the archaeology of the empire of the Incas, a four volume work from 1902 (fully available online as PDF)