Ollantaytambo

Ollantaytambo[1][2] (Quechua: Ullantaytampu) is a town and an Inca archaeological site in southern Peru some 72 km (45 mi) by road northwest of the city of Cusco. It is located at an altitude of 2,792 m (9,160 ft) above sea level in the district of Ollantaytambo, province of Urubamba, Cusco region. During the Inca Empire, Ollantaytambo was the royal estate of Emperor Pachacuti, who conquered the region,[3]:73 and built the town and a ceremonial center. At the time of the Spanish conquest of Peru, it served as a stronghold for Manco Inca Yupanqui, leader of the Inca resistance. Nowadays, located in what is called the Sacred Valley of the Incas, it is an important tourist attraction on account of its Inca ruins and its location en route to one of the most common starting points for the four-day, three-night hike known as the Inca Trail.

Ollantaytambo Ullantaytampu | |

|---|---|

Town | |

| |

Flag  Seal | |

Ollantaytambo | |

| Coordinates: 13°15′29″S 72°15′48″W | |

| Country | |

| Region | Cusco |

| Province | Urubamba |

| District | Ollantaytambo |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jose Rios Coronel |

| Elevation | 2,792 m (9,160 ft) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (PET) |

History

Around the mid-15th century, the Inca emperor Pachacuti conquered and razed Ollantaytambo; the town and the nearby region were incorporated into his personal estate.[1] The emperor rebuilt the town with sumptuous constructions and undertook extensive works of terracing and irrigation in the Urubamba Valley; the town provided lodging for the Inca nobility, while the terraces were farmed by yanakuna, retainers of the emperor.[5] After Pachacuti's death, the estate came under the administration of his panaqa, his family clan.[6]

During the Spanish conquest of Peru, Ollantaytambo served as a temporary capital for Manco Inca, leader of the native resistance against the conquistadors. He fortified the town and its approaches in the direction of the former Inca capital of Cusco, which had fallen under Spanish domination.[7] In 1536, on the plain of Mascabamba, near Ollantaytambo, Manco Inca defeated a Spanish expedition, blocking their advance from a set of high terraces and flooding the plain.[8][9]:453 Despite his victory, however, Manco Inca did not consider his position tenable, so the following year, he withdrew to the heavily forested site of Vilcabamba,[10] where he established the Neo-Inca State.

In 1540, the native population of Ollantaytambo was assigned in encomienda to Hernando Pizarro.[2]

In the 19th century, the Inca ruins at Ollantaytambo attracted the attention of several foreign explorers; among them, Clements Markham, Ephraim Squier, Charles Wiener, and Ernst Middendorf published accounts of their findings.[11]

Hiram Bingham III stopped here in 1911 on his journey up the Urubamba River in search of Machu Picchu.[12]

Description

The town of Ollantaytambo is located along the Patakancha River, close to the point where it joins the Willkanuta River. The main settlement is located on the left margin of the Patakancha with a smaller compound called 'Araqhama on the right margin. The main Inca ceremonial center is located beyond 'Araqhama on a hill called Cerro Bandolista. Several Inca structures are in the surrounding areas, and what follows is a brief description of the main sites.

Town

The main settlement at Ollantaytambo has an orthogonal layout with four longitudinal streets crossed by seven parallel streets.[13] At the center of this grid, the Incas built a large plaza that may have been up to four blocks large; it was open to the east and surrounded by halls and other town blocks on its other three sides.[14][15] All blocks on the southern half of the town were built to the same design; each comprised two kancha, walled compounds with four one-room buildings around a central courtyard.[16] Buildings in the northern half are more varied in design; however, most are in such a bad condition that their original plan is hard to establish.[17]

Ollantaytambo dates from the late 15th century and has some of the oldest continuously occupied dwellings in South America.[18] Its layout and buildings have been altered to different degrees by later constructions; for instance, on the southern edge of the town, an Inca esplanade with the original entrance to the town was rebuilt as a Plaza de Armas surrounded by colonial and republican buildings.[19] The plaza at the center of the town also disappeared, as several buildings were built over it in colonial times.[20]

'Araqhama is a western prolongation of the main settlement, across the Patakancha River; it features a large plaza, called Manyaraki, surrounded by constructions made out of adobe and semicut stones. These buildings have a much larger area than their counterparts in the main settlement; they also have very tall walls and oversized doors. To the south are other structures, but smaller and built out of fieldstones. Araqhama has been continuously occupied since Inca times, as evidenced by the Roman Catholic church on the eastern side of the plaza.[21] To the north of Manyaraki are several sanctuaries with carved stones, sculpted rock faces, and elaborate waterworks; they include the Templo de Agua and the Baño de la Ñusta.[22]

Temple Hill

'Araqhama is bordered to the west by Cerro Bandolista, a steep hill on which the Incas built a ceremonial center. The part of the hill facing the town is occupied by the terraces of Pumatallis, framed on both flanks by rock outcrops. Due to impressive character of these terraces, the Temple Hill is commonly known as the Fortress, but this is a misnomer, as the main functions of this site were religious. The main access to the ceremonial center is a series of stairways that climb to the top of the terrace complex. At this point, the site is divided into three main areas: the Middle sector, directly in front of the terraces; the Temple sector, to the south; and the Funerary sector, to the north.[23]

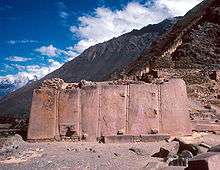

The Temple sector is built out of cut and fitted stones in contrast to the other two sectors of the Temple Hill, which are made out of fieldstones. It is accessed by a stairway that ends on a terrace with a half-finished gate and the Enclosure of the Ten Niches, a one-room building. Behind them is an open space which hosts the Platform of the Carved Seat and two unfinished monumental walls. The main structure of the whole sector is the Sun Temple, an uncompleted building which features the Wall of the Six Monoliths.[24] The Middle and Funerary sectors have several rectangular buildings, some of them with two floors; also, several fountains are in the Middle sector.[25]

The unfinished structures at the Temple Hill and the numerous stone blocks that litter the site indicate that it was still undergoing construction at the time of its abandonment. Some of the blocks show evidence of having been removed from finished walls, which provides evidence that a major remodeling effort was also underway.[26] Which event halted construction at the Temple Hill is unknown; likely candidates include the war of succession between Huáscar and Atahualpa, the Spanish Conquest of Peru, and the retreat of Manco Inca from Ollantaytambo to Vilcabamba,[27]. However it is also theorised that they are the work of a much older pre-incan culture [28]

Terraces

The valleys of the Urubamba and Patakancha Rivers along Ollantaytambo are covered by an extensive set of agricultural terraces or andenes which start at the bottom of the valleys and climb up the surrounding hills. The andenes permitted farming on otherwise unusable terrain; they also allowed the Incas to take advantage of the different ecological zones created by variations in altitude.[29] Terraces at Ollantaytambo were built to a higher standard than common Inca agricultural terraces; for instance, they have higher walls made of cut stones instead of rough fieldstones. This type of high-prestige terracing is also found in other Inca royal estates such as Chinchero, Pisaq, and Yucay.[30]

A set of sunken terraces starts south of Ollantaytambo's Plaza de Armas, stretching all the way to the Urubamba River. They are about 700 m long, 60 m wide, and up to 15 m below the level of surrounding terraces; due to their shape, they are called Callejón, the Spanish word for alley. Land inside Callejón is protected from the wind by lateral walls which also absorb solar radiation during the day and release it during the night; this creates a microclimate zone 2 to 3 °C warmer than the ground above it. These conditions allowed the Incas to grow species of plants native to lower altitudes that otherwise could not have flourished at this site.[31]

At the southern end of Callejón, overlooking the Urubamba River, is an Inca site called Q'ellu Raqay. Its interconnected buildings and plazas form an unusual design quite unlike the single-room structures common in Inca architecture. As the site is isolated from the rest of Ollantaytambo and surrounded by an elaborate terraces, it was postulated to be a palace built for emperor Pachacuti.[32]

Storehouses

The Incas built several storehouses or qullqas (Quechua: qollqa) out of fieldstones on the hills surrounding Ollantaytambo. Their location at high altitudes, where more wind and lower temperatures occur, defended their contents against decay. To enhance this effect, the Ollantaytambo qullqas feature ventilation systems. They are thought to have been used to store the production of the agricultural terraces built around the site.[33] Grain would be poured in the windows on the uphill side of each building, then emptied out through the downhill side window.[34]

Quarries

The main quarries of Ollantaytambo were located at Kachiqhata, in a ravine across the Urubamba River some 5 km from the town. The site features three main quarrying areas: Mullup'urku, Kantirayoq, and Sirkusirkuyoq; all of them provided blocks of rose rhyolite for the elaborate buildings of the Temple Hill. An elaborate network of roads, ramps, and slides connected them with the main building areas. In the quarries are several chullpas, small stone towers used as burial sites in pre-Hispanic times.[35]

Defenses

As Ollantaytambo is surrounded by mountains, and the main access routes run along the Urubamba Valley; there, the Incas built roads connecting the site with Machu Picchu to the west and Pisaq to the east. During the Spanish conquest of Peru, emperor Manco Inca fortified the eastern approaches to fend off Spanish attacks from Cusco during the Battle of Ollantaytambo. The first line of defense was a steep bank of terraces at Pachar, near the confluence of the Anta and Urubamba Rivers. Behind it, the Incas channeled the Urubamba to make it cross the valley from right to left and back, thus forming two more lines, which were backed by the fortifications of Choqana on the left bank and 'Inkapintay on the right bank. Past them, at the plain of Mascabamba, 11 high terraces closed the valley between the mountains and a deep canyon formed by the Urubamba. The only way to continue was through the gate of T'iyupunku, a thick defensive wall with two narrow doorways. To the west of Ollantaytambo, the small fort of Choquequillca defended the road to Machu Picchu. In the event of these fortifications being overrun, the Temple Hill itself with its high terraces provided a last line of defense against invaders.[36]

See also

- Sacred Valley

- List of archaeological sites in Peru

- Tourism in Peru

- List of megalithic sites

- PeruRail

References

- Protzen, Inca architecture, p. 19.

- Glave and Remy, Estructura agraria, p. 6.

- de Gamboa, P.S., 2015, History of the Incas, Lexington, ISBN 9781463688653

- Fernando E. Elorrieta Salazar & Edgar Elorrieta Salazar – Cusco and the Sacred Valley of the Incas (2005), pages 83–91 ISBN 978-603-45-0911-5

- Protzen, Inca architecture, p. 64.

- Protzen, Inca architecture, p. 27.

- Protzen, Inca architecture, p. 26.

- Protzen, Inca architecture, p. 23.

- Leon, P., 1998, The Discovery and Conquest of Peru, Chronicles of the New World Encounter, edited and translated by Cook and Cook, Durham: Duke University Press, ISBN 9780822321460

- Hemming, The conquest, pp. 222–223.

- Hemming, The conquest, pp. 559.

- Bingham, Hiram (1952). Lost City of the Incas. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 136–137. ISBN 9781842125854.

- Protzen, Inca Architecture, p. 50.

- Protzen, Inca Architecture, stones.

- Protzen, Inca Architecture, p. 52.

- Protzen, Inca Architecture, p. 53.

- Protzen, Inca architecture, p. 65.

- Kubler, The Art and Architecture, pp. 462–463.

- Protzen, Inca Architecture, pp. 48–49.

- Gasparini and Margolies, Inca Architecture, p. 71.

- Protzen, Inca Architecture, pp. 66–70.

- Protzen, Inca Architecture, p. 28.

- Protzen, Inca Architecture, pp. 73–74.

- Protzen, Inca Architecture, pp. 81–87.

- Protzen, Inca Architecture, pp. 87–91.

- Protzen, Inca architecture, pp. 92–94.

- Protzen, Inca Architecture, p. 269.

- Hatcher-Childress, Ancient Technology in Peru & Bolivia,

- Protzen, Inca architecture, pp. 30–34.

- Hyslop, Inka settlement, pp. 282–284.

- Protzen, Inca architecture, p. 97.

- Protzen, Inca architecture, pp. 102–110.

- Protzen, Inca Architecture, pp. 111–135.

- Robert Randall, referenced by Peter Frost, p148 "Exploring Cusco", 1999.

- Protzen, Inca architecture, pp. 137–153.

- Protzen, Inca architecture, pp. 22–26.

Further reading

- Bengtsson, Lisbet. Prehistoric stonework in the Peruvian Andes : a case study at Ollantaytambo. Göteborg : Etnografiska Museet, 1998. ISBN 91-85952-76-1

- Gasparini, Graziano and Luize Margolies. Inca architecture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-253-30443-1

- (in Spanish) Glave, Luis Miguel and María Isabel Remy. Estructura agraria y vida rural en una región andina: Ollantaytambo entre los siglos XVI y XIX. Cusco: Centro de Estudios Rurales Andinos "Bartolomé de las Casas", 1983.

- Hemming, John. The conquest of the Incas. London: Macmillan, 1993. ISBN 0-333-10683-0

- Hyslop, John. Inka settlement planning. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990. ISBN 0-292-73852-8

- Kubler, George. The art and architecture of ancient America: the Mexican, Maya and Andean peoples. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1990.

- Protzen, Jean-Pierre. Inca architecture and construction at Ollantaytambo. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-19-507069-0

- http://www.congreso.gob.pe/ntley/Imagenes/Leyes/27265.pdf

- Hatcher-Childress, David. "Ancient Technology in Peru & Bolivia" Adventures Unlimited Press 2012 ISBN 978-1935487814

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ollantaytambo. |

- CATCCO, local museum