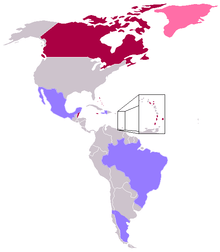

Monarchies in the Americas

There are 13 monarchies in the Americas (self-governing states and territories that have a monarch as head of state). Each is a constitutional monarchy, wherein the sovereign inherits his or her office, usually keeping it until death or abdication, and is bound by laws and customs in the exercise of their powers. Ten of these monarchies are independent states; they equally share Queen Elizabeth II, who resides primarily in the United Kingdom, as their respective sovereign, making them part of a global group known as the Commonwealth realms. The others are dependencies of three European monarchies. As such, none of the monarchies in the Americas have a permanently residing monarch.

.svg.png)

These crowns continue a history of monarchy in the Americas that reaches back to before European colonization. Both tribal and more complex pre-Columbian societies existed under monarchical forms of government, with some expanding to form vast empires under a central king figure, while others did the same with a decentralized collection of tribal regions under a hereditary chieftain. None of the contemporary monarchies, however, are descended from those pre-colonial royal systems, instead either having their historical roots in, or still being a part of, the current European monarchies that spread their reach across the Atlantic Ocean, beginning in the mid 14th century.

From that date on, through the Age of Discovery, European colonization brought extensive American territory under the control of Europe's monarchs, though the majority of these colonies subsequently gained independence from their rulers. Some did so via armed conflict with their mother countries, as in the American Revolution and the Latin American wars of independence, usually severing all ties to the overseas monarchies in the process. Others gained full sovereignty by legislative paths, such as Canada's patriation of its constitution from the United Kingdom. A certain number of former colonies became republics immediately upon achieving self-governance. The remainder continued with endemic constitutional monarchies—in the cases of Haiti, Mexico, and Brazil—with their own resident monarch and, for places such as Canada and some island states in the Caribbean, sharing their monarch with their former metropole, the most recently created being that of Belize in 1981.

Current monarchies

American monarchies

While the incumbent of each of the American monarchies is the same person and resides predominantly in Europe, each of the states are sovereign and thus have distinct local monarchies seated in their respective capitals, with the monarch's day-to-day governmental and ceremonial duties generally carried out by an appointed local viceroy.

Antigua and Barbuda

The monarchy of Antigua and Barbuda has its roots in the Spanish monarchy, under the authority of which the islands were first colonized in the late 15th century, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 1 November 1981, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Antigua and Barbuda. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Antigua and Barbuda, Sir Rodney Williams.[3]

Elizabeth and her royal consort, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, included Antigua and Barbuda in their 1966 Caribbean tour, and again in the Queen's Silver Jubilee tour of October 1977. Elizabeth returned once more in 1985.[4] For the country's 25th anniversary of independence, on 30 October 2006, Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex, opened Antigua and Barbuda's new parliament building, reading a message from his mother, the Queen. The Duke of York visited Antigua and Barbuda in January 2001.[3]

The Bahamas

The monarchy of The Bahamas has its roots in the Spanish monarchy, under the authority of which the islands were first colonized in the late 15th century, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony, after 1717. On 10 July 1973, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II,[5] as monarch of the newly formed monarchy of The Bahamas. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of the Bahamas, Sir Cornelius A. Smith.[6]

Barbados

The monarchy of Barbados has its roots in the English monarchy, under the authority of which the island was claimed in 1625 and first colonized in 1627,[7] and later the British monarchy. By the 18th century, Barbados became one of the main seats of the British Crown's authority in the British West Indies, and then, after an attempt in 1958 at a federation with other West Indian colonies, continued as a self-governing colony until, on 30 November 1966, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly formed monarchy of Barbados. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Barbados, Sir Elliott Belgrave.[8]

In 1966, Elizabeth's cousin, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, opened the second session of the first parliament of the newly established country,[7] before the Queen herself, along with Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, toured Barbados. Elizabeth returned for her Silver Jubilee in 1977, and again in 1989, to mark the 350th anniversary of the establishment of the Barbadian parliament.[7][9]

Former Prime Minister Owen Arthur called for a referendum on Barbados becoming a republic to be held in 2005,[10] though the vote was then pushed back to "at least 2006" in order to speed up Barbados' integration in the CARICOM Single Market and Economy. It was announced on 26 November 2007 that the referendum would be held in 2008, together with the general election that year.[11] The vote was, however, postponed again to a later point, due to administrative concerns.[12]

Belize

Belize was, until the 15th century, a part of the Mayan Empire, containing smaller states headed by a hereditary ruler known as an ajaw (later k’uhul ajaw).[N 1] The present monarchy of Belize has its roots in the Spanish monarchy, under the authority of which the area was first colonised in the 16th century, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 21 September 1981, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly formed monarchy of Belize.[13] The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Belize, Sir Colville Young.[14]

Canada

Canada's aboriginal peoples had systems of governance organised in a fashion similar to the Occidental concept of monarchy;[15] European explorers often referred to hereditary leaders of tribes as kings.[16] The present monarchy of Canada has its roots in the French and English monarchies, under the authority of which the area was colonised in the 16th-18th centuries, and later the British monarchy. The country became a self-governing confederation on 1 July 1867, recognised as a kingdom in its own right,[17] but did not have full legislative autonomy from the British Crown until the passage of the Statute of Westminster on 11 December 1931,[18] retaining the then reigning monarch, George V, as monarch of the newly formed monarchy of Canada. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor General of Canada, Julie Payette, and in each of the provinces by a lieutenant governor.[19]

Grenada

The monarchy of Grenada has its roots in the French monarchy, under the authority of which the islands were first colonised in the mid 17th century, and later the English and then British monarchy, as a Crown colony.[20] On 7 February 1974, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Grenada. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Grenada, currently Dame Cécile La Grenade.[21]

Jamaica

The monarchy of Jamaica has its roots in the Spanish monarchy, under the authority of which the islands were first colonised in the late 16th century, and later the English and then British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 6 August 1962, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Jamaica. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Jamaica, Sir Patrick Allen.[22]

Former Prime Minister of Jamaica Portia Simpson-Miller has expressed an intention to oversee the process required to change Jamaica to a republic by 2012; she originally stated this would be complete by August of that year.[23][24] In 2003, former Prime Minister P.J. Patterson, advocated making Jamaica into a republic by 2007.[25]

Saint Kitts and Nevis

The monarchy of Saint Kitts and Nevis has its roots in the English and French monarchies, under the authority of which the islands were first colonised in the early 17th century, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 10 June 1973, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Antigua and Barbuda.[26] The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Saint Kitts and Nevis, currently Sir Tapley Seaton.[27]

Saint Lucia

The Caribs who occupied the island of Saint Lucia in pre-Columbian times had a complex society, with hereditary kings and shamans. The present monarchy has its roots in the Dutch, French, and English monarchies, under the authority of which the island was first colonised in 1605, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 22 February 1979, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Saint Lucia.[28] The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Saint Lucia, currently Dame Pearlette Louisy.[29]

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

The present monarchy of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines has its roots in the French monarchy, under the authority of which the island was first colonised in 1719, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 27 October 1979, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines.[30] The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Vincent and the Grenadines, currently Sir Frederick Ballantyne.[31]

Settled monarchies

Denmark

Greenland is one of the three constituent countries of the Kingdom of Denmark, with Queen Margrethe II as the reigning sovereign. The territory first came under monarchical rule in 1261, when the populace accepted the overlordship of the King of Norway; by 1380, Norway had entered into a personal union with the Kingdom of Denmark, which became more entrenched with the union of the kingdoms into Denmark–Norway in 1536. After the dissolution of this arrangement in 1814, Greenland remained as a Danish colony, and, after its role in World War II, was granted its special status within the Kingdom of Denmark in 1953. The monarch is represented in the territory by the Rigsombudsmand[32] (High Commissioner), Mikaela Engell.[33]

Netherlands

Aruba, Curaçao and Sint Maarten are constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and thus have King Willem-Alexander as their sovereign, as do the islands of the Caribbean Netherlands. Aruba was first settled under the authority of the Spanish Crown circa 1499, but was acquired by the Dutch in 1634, under whose control the island has remained, save for an interval between 1805 and 1816, when Aruba was captured by the Royal Navy of King George III. The former Netherlands Antilles were originally discovered by explorers sent in the 1490s by the King of Spain, but were eventually conquered by the Dutch West India Company in the 17th century, whereafter the islands remained under the control of the Dutch Crown as colonial territories. The Netherlands Antilles achieved the status of an autonomous country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1954, from which Aruba was split in 1986 as a separate constituent country of the larger kingdom.[34] The former Netherlands Antilles was dissolved in 2010; two of its islands became constituent countries in their own right (Curaçao and Sint Maarten), while the other three became integral parts of the Netherlands (i.e., the Caribbean Netherlands). The monarch is represented in the constituent countries by the Governor of Aruba, Alfonso Boekhoudt, the Governor of Curaçao, Frits Goedgedrag,[35] and the Governor of Sint Maarten, Eugene Holiday.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom possesses a number of overseas territories in the Americas, for whom Queen Elizabeth II is monarch. In North America are Anguilla, Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, Montserrat, and the Turks and Caicos Islands, while the Falkland Islands, and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands are located in South America. The Caribbean islands were colonised under the authority or the direct instruction of a number of European monarchs, mostly English, Dutch, or Spanish, throughout the first half of the 17th century. By 1681, however, when the Turks and Caicos Islands were settled by Britons, all of the above-mentioned islands were under the control of Charles II of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Colonies were merged and split through various reorganizations of the Crown's Caribbean regions, until 19 December 1980, the date that Anguilla became a British Crown territory in its own right. The monarch is represented in these jurisdictions by: the Governor of Anguilla, Tim Foy; the Governor of Bermuda, John Rankin; the Governor of the British Virgin Islands, Gus Jaspert;[36] the Governor of the Cayman Islands, Helen Kilpatrick; the Governor of Montserrat, Andrew Pearce; and the Governor of the Turks and Caicos Islands, John Freeman.

The Falkland Islands, off the south coast of Argentina, were simultaneously claimed for Louis XV of France, in 1764, and George III of the United Kingdom, in 1765, though the French colony was ceded to Charles III of Spain in 1767. By 1833, however, the islands were under full British control. The South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands were discovered by Captain James Cook for George III in January 1775, and from 1843 were governed by the British Crown-in-Council through the Falkland Islands, an arrangement that stood until the South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands were incorporated as a distinct British overseas territory in 1985. The monarch is represented in these regions by Nigel Phillips, who is both the Governor of the Falkland Islands and the Commissioner for South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands.[37]

Succession laws

Before 28 October 2011, the succession order in the American Commonwealth realms, as well as those British overseas territories in the Americas, adhered to male-preference cognatic primogeniture, by which succession passed first to an individual's sons, in order of birth, and subsequently to daughters, again in order of birth. However, with the possible exception of Canada, following the legislative changes giving effect to the Perth Agreement, succession is by absolute primogeniture for those born after 28 October 2011, whereby the eldest child inherits the throne regardless of gender. As these states share the person of their monarch with other countries, all with legislative independence, the change was implemented only once the necessary legal processes were completed in each realm. Those possessions under the Danish and Dutch crowns already adhere to absolute primogeniture.[38][39][40]

Former monarchies

Most pre-Columbian cultures of the Americas developed and flourished for centuries under monarchical systems of government. By the time Europeans arrived on the continents in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, however, many of these civilizations had ceased to function, due to various natural and artificial causes. Those that remained up to that period were eventually defeated by the agents of European monarchical powers, who, while they remained on the European continent, thereafter established new American administrations overseen by delegated viceroys. Some of these colonies were, in turn, replaced by either republican states or locally founded monarchies, ultimately overtaking the entire American holdings of some European monarchs; those crowns that once held or claim territory in the Americas include the Spanish, Portuguese, French, Swedish, and Russian, and even Baltic Courland, Holy Roman, Prussian and Norwegian. Certain of the locally established monarchies were themselves also overthrown through revolution, leaving five current pretenders to American thrones.

Endemic monarchies

Araucania and Patagonia

The Kingdom of Araucania and Patagonia was a short-lived attempt at establishing a constitutional monarchy, founded by French lawyer and adventurer Orelie-Antoine de Tounens in 1860. Nominally, the "kingdom" encompassed the present-day Argentine part of Patagonia and a small segment of Chile, where Mapuche peoples were fighting to maintain their sovereignty against the advancing Chilean and Argentine armed forces.[41] However, Orélie-Antoine never exercised sovereignty over the claimed territory, and his de facto control was limited to nearly fourteen months and to a small territory around a town called Perquenco (at the time mainly a Mapuche tent village), which was also the declared capital of his kingdom.

Orélie-Antoine felt that the indigenous peoples would be better served in negotiations with the surrounding powers by a European leader,[41] and was accordingly elected by a group of Mapuche loncos (chieftains) to be their king.[42] He made efforts to gain international recognition, and attempted to involve the French government in his project, but these efforts proved unsuccessful: the French consul concluded that Tounens was insane, and Araucania and Patagonia was never recognized by any country. The Chileans primarily ignored Orélie-Antoine and his kingdom, at least initially, and simply went on with the occupation of the Araucanía, a historical process which concluded in 1883 with Chile establishing control over the region. In the process, Orélie-Antoine was captured in 1862, and imprisoned in an insane asylum in Chile. After several fruitless attempts to return to his kingdom (thwarted by Chilean and Argentine authorities), Tounens died penniless in 1878 in Tourtoirac, France. A recent pretender, Prince Antoine IV, lived in France until 2017. The previous pretender renounced his claims to the Patagonian throne,[43] even though a few Mapuches continue to recognise the Araucanian monarchy.[42]

Aztec

The Aztec Empire existed in the central Mexican region between c. 1325 and 1521, and was formed by the triple alliance of the tlatoque (the Nahuatl term for "speaker", also translated in English as "king") of three city-states: Tlacopan, Texcoco, and the capital of the empire, Tenochtitlan.[44] While the lineage of Tenochtitlan's kings continued after the city's fall to the Spanish on 13 August 1521, they reigned as puppet rulers of the King of Spain until the death of the last dynastic tlatoani, Luis de Santa María Nanacacipactzin, on 27 December 1565.[45]

Brazil

Brazil was created as a kingdom on 16 December 1815, when Prince João, Prince of Brazil, who was then acting as regent for his ailing mother, Queen Maria, elevated the colony to a constituent country of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves.[46] While the royal court was still based in Rio de Janeiro, João ascended as king of the united kingdom the following year, and returned to Portugal in 1821,[47] leaving his son, Prince Pedro, Prince Royal, as his regent in the Kingdom of Brazil. In September of that same year, the Portuguese parliament threatened to diminish Brazil back to the status of a colony, dismantle all the royal agencies in Rio de Janeiro, and demanded Pedro return to Lisbon.[47] The Prince, however, feared these moves would trigger separatist movements and refused to comply; instead, at the urging of his father, he declared Brazil an independent Nation on 7 September 1822, leading to the formation of the Empire of Brazil, a constitutional monarchy.

Prince Pedro became the first Emperor of Brazil on 12 October 1822, with the title of Pedro I (on that date, he was formally offered the Throne of the newly created Empire, accepted it, and was acclaimed as monarch), and his coronation took place on 1 December 1822.[48] After Pedro abdicated the throne on 7 April 1831, the Brazilian empire saw only one additional monarch: Pedro II,[47] who reigned for 58 years before a coup d'état overthrew the monarchy on 15 November 1889. There are two pretenders to the defunct Brazilian throne: Prince Luiz of Orléans-Braganza, head of the Vassouras branch of the Brazilian Imperial Family, and, according to legitimist claims, de jure Emperor of Brazil; and Prince Pedro Carlos of Orléans-Braganza, head of the Petrópolis line of the Brazilian Imperial Family, and heir to the Brazilian throne according to royalists.[49]

The Brazilian constitution of 1988 called for a general vote on the restoration of the monarchy, which was held in 1993. The royalists went to the polls divided, with the press indicating there were actually two princes aspiring to the Brazilian throne (Dom Luiz de Orleans e Bragança and Dom João Henrique); this created some confusion among the voters.

Haiti

The entire island of Hispaniola was first claimed on 5 December 1492, by Christopher Columbus, for Queen Isabella, and the first Viceroy of the Americas was established along with a number of colonies throughout the Island. With the later discovery of Mexico and Peru many of the early settlers left for the main land, but some twelve cities and a hundred thousand souls remained, mainly in the Eastern part of the Island. Through the Treaty of Riswick in 1697, King Louis XIV received the western third of the Island from Spain as retribution and formalized the first French pirate settlement in existence since the mid-1600s,[50] with the colony administered by a governor-general representing the French crown,[51] an arrangement that stood until the French Revolution toppled the monarchy of France on 21 September 1792. Though the French government retained control over the region of Saint-Domingue, on 22 September 1804, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, who had served as Governor-General of Saint-Domingue since 30 November 1803, declared himself as head of an independent Empire of Haiti, with his coronation as Emperor Jacques I taking place on 6 October that year. After his assassination on 17 October 1806, the country was split in half, the northern portion eventually becoming the Kingdom of Haiti on 28 March 1811, with Henri Christophe installed as King Henri I.[52] When King Henri committed suicide on 8 October 1820, and his son, Jacques-Victor Henry, Prince Royal of Haiti, was murdered by revolutionaries ten days later, the kingdom was merged into the southern Republic of Haiti, of which Faustin-Élie Soulouque was elected president on 2 March 1847. Two years later, on 26 August 1849, the Haitian national assembly declared the president as Emperor Faustin I, thereby re-establishing the Empire of Haiti. But this monarchical reincarnation was to be short lived as well, as a revolution broke out in the empire in 1858, resulting in Faustin abdicating the throne on 18 January 1859.[53]

Inca

The Inca Empire spread across the north western parts of South America between 1438 and 1533, ruled over by a monarch addressed as the Sapa Inca, Sapa, or Apu. The Inca civilization emerged in the Kingdom of Cusco, and expanded to become the Ttahuantin-suyu, or "land of the four sections", each ruled by a governor or viceroy called Apu-cuna, under the leadership of the central Sapa Inca. The Inca Empire eventually fell to the Spanish in 1533, when the last Sapa Inca of the empire, Atahualpa, was captured and executed on 29 August.[54] The conquerors installed other Sapa Inca beginning with Atahualpa's brother, Túpac Huallpa. Manco Inca Yupanqui, originally also a puppet Inca Emperor installed by the Spaniards, rebelled and founded the small independent Neo-Inca State in Vilcabamba, and the line continued until the death of Túpac Amaru in 1572.[55]

Maya

The Maya civilization was located on the Yucatán Peninsula and into the isthmian portion of North America, and the northern portion of Central America (Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador and Honduras) was formed of a number of ajawil, ajawlel, or ajawlil– hierarchical polities headed by an hereditary ruler known as a kuhul ajaw (the Mayan term indicating a sovereign leader).[N 1] Despite constant warfare and shifts in regional power, most Maya kingdoms remained a part of the region's landscape, even following subordination to hegemonic rulers through conquest or dynastic union. Nonetheless, the Maya civilization began its decline in the 8th and 9th centuries, and by the time of the arrival of the Spanish, only a few kingdoms remained, such as the Peten Itza kingdom, Mam, Kaqchikel, and the K'iche' Kingdom of Q'umarkaj. On 13 March 1697, the last Itza Maya king was defeated at Nojpetén by the forces of King Philip IV of Spain.[56]

Mexico

With the victory of the Mexicans over the Spanish imperial army in 1821, the Viceroyalty of New Spain came to a conclusion. The newly independent Mexican Congress still desired that King Ferdinand VII, or another member of the House of Bourbon, agree to be installed as Emperor of Mexico, thereby forming a type of personal union with Spain. The Spanish monarchy, however, refused to recognise the new state, and decreed that it would allow no other European prince to take the throne of Mexico. Thus, the Mexican Agustín de Iturbide was crowned as Augustine I on 19 May 1822, with an official decree of confirmation issued two days following. Only a few months later, Augustine dissolved a factious congress, thereby prompting an enraged Antonio López de Santa Anna to mount a coup, which led to the declaration of a republic on 1 December 1822. In order to end the unrest, Augustine abdicated on 19 March 1823 and left the country, and the Mexican monarchy was abolished. After hearing that the situation in Mexico had only grown worse since his abdication, Iturbide returned from England on 11 May 1824, but was detained upon setting foot in Mexico and, without trial, was executed.[57]

Benito Juárez, elected as President of Mexico on 19 January 1858, suspended all repayments on Mexico's foreign debts (save those owed to the United States), leading France, the United Kingdom, and Spain to send a joint expeditionary force that took Veracruz in December 1861. Juárez then repaid the debts, after which British and Spanish troops withdrew, but Emperor Napoleon III of France used the situation as a pretext to overthrow the republic and install a monarch friendly to the interests of France. Archduke Maximilian, brother of the Emperor of Austria, was elevated as Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico, thereby re-establishing the Mexican monarchy, but the new emperor ultimately did not bow to Napoleon's wishes, leading the latter to withdraw the majority of his influence from Mexico. Regardless, Maximilian was still viewed as a French puppet, and an illegitimate leader of the country. As well, at the end of the American Civil War, US troops moved to the Mexico-US border as part of a planned invasion, seeing the establishment of the Second Mexican Empire as an infringement on their Monroe Doctrine. Backed by the Americans, ex-president Juárez mobilised to retake power, and defeated Maximilian at Querétaro on 15 May 1867. The Emperor was arraigned before a military tribunal, sentenced to death, and executed at the Cerro de las Campanas on 19 June 1867.[58]

Miskito

The Miskito people of Central America were governed by the authority of a monarch, but one who shared his royal powers with a governor and a general. The origins of the monarchy are unknown; however, its sovereignty was lost when King Edward I of the Miskito Nation signed the Treaty of Friendship and Alliance with King George II of the United Kingdom, putting the Miskito kingdom under the British protection and law. At the cessation of the American Revolutionary War, King George III of the United Kingdom, via the Treaty of Paris, relinquished control of the Miskito's lands, though Britain continued an unofficial protectorate over the kingdom to protect Miskito interests against Spanish encroachments. After British interest in the region waned, Nicaragua dissolved and occupied the Miskito kingdom in 1894,[59] with the monarch thereafter becoming known as the Hereditary Chief. Norton Cuthbert Clarence is the current pretender to the Miskito Kingdom and Hereditary Chief of the Miskito Nation.[60]

Taíno

The Taínos were an indigenous civilization spread across those islands today lying within the Bahamas, Greater Antilles, and the northern Lesser Antilles. These regions were divided into kingdoms (the island of Hispaniola alone was segmented into five kingdoms), which were themselves sometimes sub-divided into provinces. Each kingdom was led by a cacique, or "chieftain", who was advised in his exercise of royal power by a council of priests/healers known as bohiques.[61] The line of succession, however, was matrilineal, whereby if there was no male heir to become cacigue, the title would pass to the eldest child, whether son or daughter, of the deceased's sister.[62] After battling for centuries with the Carib, the Taíno empire finally succumbed to disease and genocide brought by the Spanish colonisers.[63][64]

Colonial monarchies

Courland

After a number of failed attempts at colonising Tobago, Duke Jacob Kettler of Courland and Semigallia sent one more ship to the island, which landed there on 20 May 1654, carrying soldiers and colonists, who named the island New Courland. At approximately the same time, Dutch colonies were established at other locations on the island, and eventually outgrew those of the Duchy of Courland in population. When the Duke was captured by Swedish forces in 1658, Dutch settlers overtook the Courland colonies, forcing the Governor to surrender. After a return of the territory to Courland through the 1660 Treaty of Oliwa, a number of attempts were made by the next Duke of Courland (Friedrich Casimir Kettler) at re-colonisation, but these met with failure, and he sold New Courland in 1689.[65]

France

After King Francis I commissioned Jacques Cartier to search out an eastern route to Asia, the city of Port Royal was founded on 27 July 1605 in what is today Nova Scotia. From there, the French Crown's empire in the Americas grew to include areas of land surrounding the Great Lakes and down the Mississippi River, as well as islands in the Caribbean, and the north eastern shore of South America; the Viceroyalty of New France was eventually made into a royal province of France in 1663 by King Louis XIV.[66] Some regions were lost to the Spanish or British Crowns through conflict and treaties, and those that were still possessions of the French king on 21 December 1792 came under republican rule when the French monarchy was abolished on that day.[67][68] Upon several restorations of the monarchy, the royal presence in the Americas ended with the collapse of the Second French Empire under Napoleon III in 1870.

.jpg)

Russia

The first permanent Russian settlements in what is today the US state of Alaska were set down in the 1790s, forming Russian Alaska, after Tsar Peter I called for expeditions across the Bering Strait in 1725,[69] with the region administered by the head of the Russian-American Company as the Emperor's representative. Another Russian outpost, Fort Ross, was established in 1812 in what is now California.[70] The colonies, however, were never profitable enough to maintain Russian interest in the area, with the population only ever reaching a maximum of 700. Fort Ross was sold in 1841, and in 1867, a deal was brokered whereby Tsar Alexander II sold his Alaskan territory to the United States of America for $7,200,000, and the official transfer took place on 30 October that year.[71]

Portugal

The United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves came into being in the wake of Portugal's war with Napoleonic France. The Portuguese Prince Regent, the future King John VI, with his incapacitated mother, Queen Maria I of Portugal and the Royal Court, escaped to the colony of Brazil in 1808. With the defeat of Napoleon in 1815, there were calls for the return of the Portuguese Monarch to Lisbon; the Portuguese Prince Regent enjoyed life in Rio de Janeiro, where the monarchy was at the time more popular and where he enjoyed more freedom, and he was thus unwilling to return to Europe. However, those advocating the return of the Court to Lisbon argued that Brazil was only a colony and that it was not right for Portugal to be governed from a colony. On the other hand, leading Brazilian courtiers pressed for the elevation of Brazil from the rank of a colony, so that they could enjoy the full status of being nationals of the mother-country. Brazilian nationalists also supported the move, because it indicated that Brazil would no longer be submissive to the interests of Portugal, but would be of equal status within a transatlantic monarchy.

Spain

Beginning in 1492 with the voyages of Christopher Columbus under the direction of Isabella I of Castile, the Spanish Crown amassed a large American empire over three centuries, spreading first from the Caribbean to Central America, most of South America, Mexico, what is today the Southwestern United States, and the Pacific coast of North America up to Alaska.[72][73] These regions formed the majority of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, the Viceroyalty of Peru, the Viceroyalty of New Granada, and the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata in each of which the Spanish monarch was represented by a viceroy. By the early 19th century, however, the Spanish sovereign's possessions in the Americas began a series of independence movements, which culminated in the Crown's loss of all its colonies on the mainland of North and South America by 1825. The remaining colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico were occupied by the United States following the Spanish–American War, ending Spanish rule in the Americas by 1899.[74]

Sweden

For a period of time the French ceded sovereignty of the island of Saint Barthélemy to the Swedes but it was eventually returned. Saint Barthélemy (1784–1878) was operated as a porto Franco (free port). The capital city of Gustavia retains its Swedish name.

Self-proclaimed monarchies

.jpg)

These entities were never recognized de jure as legitimate governments, but still sometimes exercised a certain degree of local control or influence within their respective locations until the death of their "monarch":

- James J. Strang

James Strang, a would-be successor to the Mormon prophet Joseph Smith, Jr., proclaimed himself "king" over his church in 1850, which was then concentrated mostly on Beaver Island in Lake Michigan. On 8 July of that year, he was physically crowned in an elaborate coronation ceremony complete with crown, sceptre, throne, ermine robe and breastplate.[75] Although he never claimed legal sovereignty over Beaver Island or any other geographical entity, Strang managed (as a member of the Michigan State Legislature) to have his "kingdom" constituted as a separate county, where his followers held all county offices, and Strang's word was law. U.S. President Millard Fillmore ordered an investigation into Strang's colony, which resulted in Strang's trial in Detroit for treason, trespass, counterfeiting and other crimes, but the jury found the "king" innocent of all charges. Strang was eventually assassinated by two disgruntled followers in 1856, and his kingdom—together with his royal regalia—vanished.

- Joshua Norton

Joshua Abraham Norton, an Englishman who emigrated to San Francisco, California in 1849, proclaimed himself "Emperor of These United States" in 1859, later adding the title "Protector of Mexico". Though never recognized by the U.S. or Mexican governments, he was accorded a certain degree of deference within San Francisco itself, including reserved balcony seats (for which he was never charged) at local theatres, and salutes by policemen who passed him on the street. Specially printed currency authorized by Norton was accepted as legal tender within several businesses in the city. When Norton died in 1880, he was given a lavish funeral attended by over 30,000 persons.[76]

- James Harden-Hickey

James Harden-Hickey was a self-proclaimed prince, who attempted to establish the so-called Principality of Trinidad on Trindade and the Martim Vaz Islands in the South Atlantic Ocean during the late 19th century. Although initially garnering some newspaper attention, Hickey's claims were ignored or ridiculed by other nations, and the islands eventually were occupied by military forces from nearby Brazil which remain there to the present day.

- Matthew Dowdy Shiell

A self-proclaimed monarch of the so-called Kingdom of Redonda, an island in the Caribbean Sea. Whether Shiell ever actually claimed to be king of this tiny islet is open to debate; however, other individuals later claimed the title of "King of Redonda," without having apparently ever tried to physically establish themselves on the island itself.

See also

- Afro-Bolivian monarchy

- Canadian Confederation

- List of monarchs in the Americas

- List of the last monarchs in the Americas

- Monarchies in Africa

- Monarchies in Europe

- Monarchies in Oceania

- Monarchism

Notes

- Both terms appear in early Colonial texts (including Papeles de Paxbolón) where they are used as synonymous to Aztec and Spanish terms for supreme rulers and their domains – tlahtoani (Tlatoani) and tlahtocayotl, rey, or magestad and reino, señor and señorío, or dominio.

References

- Department of Canadian Heritage. "Ceremonial and Canadian Symbols Promotion > The Canadian Monarchy > The Queen's Personal Canadian Flag". Queen's Printer for Canada. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- Royal Household at Buckingham Palace. "Mailbox". Royal Insight Magazine. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office (September 2006). Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office. "Country profiles > North & Central America and Caribbean > Antigua and Barbuda". Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Archived from the original on 19 January 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- Royal Household at Buckingham Palace. "The Monarchy Today > Queen and Commonwealth > Other Caribbean realms". Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- Government of the Bahamas. "The Government of the Bahamas > About The Government > Overview and Structure of the Government". Government of the Bahamas. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- media. "The Cabinet Office announces The Honourable Cornelius A. Smith to serve as the 11th Governor-General in an Independent Bahamas! | Bahamaspress.com". Retrieved 27 June 2019.

- The Clerk Of Parliament. "The Barbados Parliament > Parliament's History". Parliament of Barbados. Archived from the original on 23 May 2007. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- Government Information Service. "Government > Governor General". Government of Barbados. Archived from the original on 18 November 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- Royal Household at Buckingham Palace. "The Monarchy Today > Queen and Commonwealth > Other Caribbean Realms". Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- Thomas, Norman (7 February 2005). "Barbados to vote on move to republic". Caribbean News. Archived from the original on 28 December 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- Staff (26 November 2007). "Referendum on Republic to be bundled with election". Caribbean Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 27 November 2007.

- Gollop, Chris (2 December 2007). "Vote Off". The Nation. Archived from the original on 28 December 2007. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

- Government of Belize. "About Belize > Politics > Constitution and Government". Government of Belize. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office. "Country profiles > North & Central America and Caribbean > Belize". Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Kehoe, Alice Beck (October 2001). "First Nations History". The World & I Online. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- Simon, John. "Engravings of the Four Kings: More Than Meets the Eye". Pequot Museum. Archived from the original on 21 November 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- Department of Canadian Heritage. "The Crown in Canada". Queen's Printer for Canada. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- MacLeod, Kevin S. A Crown of Maples: Constitutional Monarchy in Canada (PDF). Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada. ISBN 978-0-662-46012-1. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- Government House. "Role and duties of the Lieutenant-Governor". Memorial University. Archived from the original on 23 February 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office. "Country profiles > North & Central America and Caribbean > Grenada". Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Archived from the original on 21 January 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- "Grenada". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 1 December 2008.

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office. "Country profiles > North & Central America and Caribbean > Jamaica". Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Archived from the original on 19 January 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- "Jamaica plans to become a republic". Sky News Australia. 31 December 2011. Retrieved 31 December 2011.

- "Jamaica to break links with Queen, says Prime Minister Simpson Miller". BBC News. 6 January 2012. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- Staff (22 September 2003). "Jamaica eyes republican future". BBC. Retrieved 14 December 2008.

- "About Government". Government of Saint Kitts and Nevis. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- "Country Profile: Saint Kitts and Nevis". Foreign and Commonwealth Office (UK). Archived from the original on 9 December 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office. "Country profiles > North & Central America and Caribbean > Saint Lucia". Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Archived from the original on 21 January 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- Government Information Service. "Government of Saint Lucia > Office of the Governor General". Government of Saint Lucia. Archived from the original on 28 April 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- Royal Household at Buckingham Palace. "The Monarchy Today > Queen and Commonwealth > Other Caribbean Realms". Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- Foreign and Commonwealth Office. "Country profiles > North & Central America and Caribbean > Saint Vincent and the Grenadines". Her Majesty's Stationery Office. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- "Home Rule Act of the Faroe Islands". Prime Minister of Denmark. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- "Greenland". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- "Aruba". MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 1 November 2009. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- "Who is Governor Frits Goedgedrag?". Official Website of the Governor of the Netherlands Antilles. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- "HM Governor". HM Government of the British Virgin Islands. Retrieved 5 January 2009.

- "Falklands' Swearing in Ceremony for Governor Phillips on 12 September". MercoPress. 2 September 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- "Succession to the throne". Dutch Monarchy. Archived from the original on 22 August 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- Females get the nod in Denmark

- "Suggested changes to the Succession". Parliament of Denmark. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 25 January 2009. (In Danish)

- "Histoiry of the King Orllie-Antoine". Kingdom of Araucania & Patagonia. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- Marhique, Huichacurha. "The Kingdom of Araucania and Patagonia". Kingdom of Araucania & Patagonia. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- Menéndez, Braun (1959). Pequeña historia patagónica (in Spanish). Emecé Editores. p. 128.

- Hamnett, Brian R. (1999). A Concise History of Mexico. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-521-58916-1. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

Aztec Triple Alliance.

- de San Antón Muñón Chimalpahin Cuauhtlehuanitzin, Domingo Francisco; Arthur J. O. Anderson; Susan Schroeder; Wayne Ruwet (1997). Codex Chimalpahin. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8061-2950-1.

- Vianna, Hélio (1994). História do Brasil: período colonial, monarquia e república (in Spanish). São Paulo: Melhoramentos.

- Miller, James. "Pedro II, Emperor of Brazil". Historical Text Archive. Archived from the original on 22 February 2008. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

- Vainfas, Ronaldo (2002). Dicionário do Brasil Imperial (in Spanish). Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva.

- Handler, Bruce (5 March 1989). "Brazil to Decide on Return of Monarchy". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. p. 34.

- Haggerty, Richard A. (1989). "Haiti, A Country Study: French Settlement and Sovereignty". US Library of Congress. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- "Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online > Emmanuel-Auguste de Cahideuc, Comte Dubois de la Motte". University of Toronto/Université Laval. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- Cheesman, Clive (2007). The Armorial of Haiti. London: The College of Arms. ISBN 978-0-9506980-2-1. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- Rogozinski, Jan (1999). A Brief History of the Caribbean (Revised ed.). New York: Facts on File, Inc. p. 220. ISBN 0-8160-3811-2.

- Inca Empire: Spanish Conquest. MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 2 November 2009. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- Túpac Amaru. MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 1 November 2009. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- Sharer, Robert J.; Sylvanus Griswold Morley (1994). The Ancient Maya. Stanford University Press. p. 423. ISBN 978-0-8047-2130-1.

- "History » Independence » The Mexican Empire, 1821–23". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- "History » Independence » French intervention". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- Carroll, Rory (26 November 2006). "Nicaragua's green lobby is leaving rainforest people 'utterly destitute'". Guardian Unlimited. London. Retrieved 7 September 2007.

- Naylor, Robert A. (1989). Penny Ante Imperialism: The Mosquito Shore and the Bay of Honduras. University of Virginia. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-8386-3323-6.

- "Caciques, nobles and their regalia". elmuseo.org. Archived from the original on 9 October 2006. Retrieved 9 November 2006.

- Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos: Rise and Decline of the people who greeted Columbus. New York: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-05696-6.

- Sale, Kirkpatrick. The Conquest of Paradise. p. 157. ISBN 0-333-57479-6.

- "Taíno people". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- "Dutch Portuguese Colonial History > Dutch and Courlanders in Tobago". Colonialvoyage.com. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- Emerson, Rupert (January 1969). "Colonialism and Decolonization". Journal of Contemporary History. 4 (1): 3–16. doi:10.1177/002200946900400101.

- Hibbert, Christopher (1980). The Days of the French Revolution. New York: Quill, William Morrow. ISBN 0-688-03704-6. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- Lefebvre, Georges (1971). The French Revolution: From Its Origins to 1793. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08598-2. Retrieved 2 January 2009.

- "Alaska History Timeline". Kodiak Island Internet Directory. Retrieved 19 December 2008.

- Nordlander, David J. (1994). For God & Tsar: A Brief History of Russian America 1741–1867. Anchorage: Alaska Natural History Association. ISBN 0-930931-15-7.

- Farrar, Victor John (1966). The Annexation of Russian America to the United States. New York: Russell & Russell.

- Bartroli, Tomás (1968). Presencia hispánica en la costa noroeste de América (in Spanish). Vancouver: Universidad de British Columbio.

- Miró, Angelina. Catalans a la costa oest del Canadà: Els catalans a la Colúmbia Britànica al s.XVIII (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 October 2008. Retrieved 19 December 2008.

- Lee, Stacey (October 2002). Mexico and the United States. Marshall Cavendish. p. 777. ISBN 978-0-7614-7402-9.

- Weeks, Robert P. "For His Was the Kingdom, and the Power, and the Glory...Briefly" American Heritage 21 (4). The sceptre is preserved in the vault of the archives of the Community of Christ church in Independence, Missouri; the whereabouts of Strang's remaining regalia is a mystery.

- Norton I, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico

Sources

- Central Intelligence Agency (11 July 2006). "CIA — The World Factbook". The World Factbook. Retrieved 25 November 2008.

- Central Intelligence Agency (18 July 2006). "World Leaders". World Leaders. Retrieved 25 November 2008.