Cholula (Mesoamerican site)

Cholula (Spanish: [tʃoˈlula] (![]()

Location and environment

Cholula is located in the Puebla-Tlaxcala Valley of the central Mexican highlands. It is surrounded to the west by the snow-covered peaks Popocatepetl and Iztaccihuatl, and Malinche to the north. The summer rainy season and the melted snow in winter provide a great environment for irrigation agriculture. There is also a confluence of several perennial streams with the Atoyac River that creates a wetland to the north and east of the urban center. This has resulted in abundant and excellent agriculture during the colonial period, which led to Cholula being known as the richest agricultural region in central Mexico. Maize is the major crop cultivated but they also harvested maguey, chiles, and cochineal for dye. The soil is rich in clay, which made pottery and brick-making an important part of their economy. Textiles and elaborate decorative capes were also popular.[1]

Economy and trade

Cholula’s strategical location in the center of the Mexican highlands gives it a prime place as a trade outpost. Here, trade routes connected the Gulf coast, the Valley of Mexico, Tehuacan Valley, and La Mixteca Baja through Izucar de Matamoros.[1] From there, trade routes went to the Pacific coast, where the longer Pacific Coast communication and trade route existed.

Because of its location, Cholula served as the link center where primary trade routes and alliance corridors linked Post-Classic groups of Tolteca-Chichimeca kingdoms with southern Mesoamerica.[2]

Textile production

Textiles were of extreme importance for Cholula’s economy. During the Postclassic period they were a common unit of tribute and exchange. Textiles were manufactured for local consumption and traded extensively by different merchants that frequented the city. Textile production accounts are provided by ethnohistorical and archaeological sources. Spanish writings from Colonial times have noted their excellence in dying techniques and ability to dye wool threads in diverse colors to produce a variety of textiles. Some of the materials they used were cotton, which was probably imported from the Gulf Coast or Southern Puebla, and maguey, feathers, rabbit fur, tree silk, milkweed, and human hair that were all locally found. Artifacts such as spindle whorls found at different Cholula site loci provide evidence for the extensive production of textiles in the site. These are rare from the Formative and the Classic periods but become more prevalent in the Postclassic. Only unbaked-clay whorls may have been used during the earlier periods but these are not preserved in the archaeological record. The high concentration of spindle whorls recovered from Cholula in comparison to other Mesoamerican sites attests to the important role they played in their economy.[3]

History

Cholula grew from a very small village to a regional center between CE 600 and 700 ce. During this period, Cholula was a major center contemporaneous with Teotihuacan and seems to have avoided, at least partially, that city's fate of violent destruction at the end of the Mesoamerican Classic period.

The earliest occupation dates back to the Early Formative period. In the 1970s, Mountjoy discovered a waterlogged deposit dating to the late Middle Formative period near the ancient lakeshore. The earliest construction evidence at Cholula dates to the Late Formative period. Initial stages of the Great Pyramid probably date to the Terminal Formative Period and show stylistic resemblance to early Teotihuacan. Estimates suggest that during the Formative period the site extended for about 2 square kilometers, with a population of five to ten thousand.[1]

The Classical period is known for the construction of the Great Pyramid. At least stages 3 and 10 were built during this period and many other mounds of the urban zone, like the Cerro Cocoyo, Edificio Rojo, San Miguelito and the Cerro Guadalupe, were also constructed at this point in time. The central ceremonial precinct included the Great Pyramid, a big plaza to the west, and the Cerro Cocoyo as the west most pyramid of the plaza group. Classical period Cholula most likely covered around 5 square kilometers, and had an estimated population of fifteen to twenty thousand individuals.[1]

During the Early Postclassic there might have been an ethnic change, suggested by the influx of Gulf Coast motifs and by the burial at the pyramid of an individual with Maya-style cranial modification and inlaid teeth.[1]

Cholula reached its maximum size and population during the Postclassic period. It covered 10 square kilometers and had a population of thirty to fifty thousand. During this period, ethnic changes divide the historical sequence into two phases: the Tlachihualtepetl and Cholollan phases. The Tlachihualtepetl phase (CE 700–1200) is named after the city of the Great Pyramid as it was recorded in the Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca ethnohistoric source.[1] During this phase according to the ethnohistoric accounts, Cholula was taken over by the Gulf Coast group known as the Olmec-Xicallanca, who made it their capital. From there, they controlled the high plateau of Puebla and Tlaxcala. Under this group, the potters of Cholula began to develop the fine polychrome wares that were to become the most popular vessels in all of ancient Mexico.[4]

In CE 1200, ethnic Tolteca-Chichimeca conquered Cholula. At this point, the Patio of the Altars was destroyed and the ceremonial center (with the “new” Pyramid of Quetzalcoatl) was moved to the present zócalo (main plaza) of Cholula. Polycrome pottery from this phase used distinctive design configurations but was derived from the earlier styles. The “laca” pottery also dates to this period.[1]

During this entire period, Cholula remained a regional center of importance, enough so that, at the time of the fall of the Aztec Empire, Aztec princes were still formally anointed by a Cholulan priest.

At the time of the arrival of Hernán Cortés, Cholula was second only to the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan (modern Mexico City) as the largest city in central Mexico, possibly with a population of up to 100,000 people. In addition to the great temple of Quetzalcoatl and various palaces, the city had 365 temples.

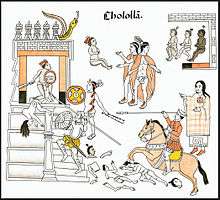

In 1519, Cortes and his troops were allowed to rest and stay in the city on their way to Tenochtitlan, however, at the request of Montezuma II, the Cholulans began plotting an ambush to kill the Spaniards. Trenches and holes with spikes were prepared and women and children evacuated. Upon this discovery, Cortes had the main warriors and nobles brought to him, had them massacred at the central plaza and partially burned the city to make an example of the Cholulans for what he considered treason.[5]

A few years later, Cortés vowed that the city would be rebuilt with a Christian church to replace each of the old pagan temples; fewer than 50 new churches were actually built, but the Spanish colonial churches are unusually numerous for a city of its size. There is a common saying in Cholula that there is a church for every day of the year.

During the Spanish colonial period, Cholula was overtaken in importance by the nearby newly-founded Spanish city of Puebla.

Great Pyramid of Cholula

The Great Pyramid of Cholula, Tlachihualtepetl, is the largest prehispanic structure in the world in terms of volume.[1] It is the result of four successive superpositions, the first two from the Classic period.[6] Stage one measured about 120 m (394 ft) on the side and was 17 m (56 ft) high. The top platform measured about 43 m (141 ft) square and featured wall remains of the temple precinct.[1]

The earliest pyramid exhibits the talud-tablero motif style and is painted with insects resembling a Teotihuacan style. When the pyramid was originally built in 300 BCE, there were insects painted in black, red, and yellow on it.[7] The second pyramid, which was built over the first one, no longer resembles Teotihuacan architectural style. Instead it is a pyramid with stairs covering all four sides, so the top could be approached from every direction. It measures 590 ft (180 m) on a side.[6] The exposed slopes of the pyramid are earth- and adobe-filled and represent the last construction phase between CE 750 and 950.[2] During the Early Postclassic period, the pyramid was expanded to its final form. It covered 16 hectares (400 meters on the side) and reached a height of 66 meters. The orientation of the Great Pyramid, and the whole site’s urban grid, is about 26 degrees north of west, a deviation from Teotihuacan’s orientation. This orientation is aligned with the summer solstice, and it may relate to the worship of a solar deity related to the Mixtec 7 Flower, or Aztec Tonacatecuhtli.[1]

Today Cholula is still one of the most important pilgrimage destinations in Mexico. Around 350,000 people attend the annual festival centered at the top of the Great Pyramid.[1] The Great Pyramid of Cholula is still used because the Spanish built a church atop it, a symbol of the religious conquest of Mexico. That makes it not just the largest pyramid in the world but also the oldest continuously occupied building in North America. In the 20th century, the temple was tunnelled by archaeologists. Four major and nine minor construction stages were revealed. These tunnels remain open to visitors and are stable because of the adobe bricks that were used to build the pyramid.[7]

Art

The origins of the Mixteca-Puebla stylistic tradition appeared and reflected the Gulf Coast influences. Polychrome pottery was already common by CE 1000, and also resembles Gulf Coast styles.[1]

The mural known as The Drunkards is a 165 ft (50 m) long polychrome mural with life size human figures. The scene represented is one of drinking and inebriation but the liquid being ingested could have been derived from hallucinogenic mushrooms of ancient Mexico or peyote, rather than alcohol.[6]

Figurines

Figurines in Cholula are prominent. On an excavation located at the southwestern extreme of the Universidad de las Américas in Cholula one of the features was a 3.68-m-deep Prehispanic water well that kept Postclassic ceramics and figurines, which accounted for most of the artifacts found. There were 110 figurines and no molds were found; although some molds have been found by other archaeologists in the area. Together with the figurines was a large amount of re-constructible broken figurines and others that were over fired or even blackened and burned. Also, the presence of scoria, pigments, polishing tools, balls of prepared clay, and vitrified abode blocks suggest that these materials may have been waste products from a workshop in the neighborhood.[8]

The figurines usually represent deities like in many other Mesoamerican sites, but their shape is unique. They are façades of about 19 cm high. The front of the figurines are a fairly complex face and headdress set upon a plain trapezoidal pedestal. The back is very roughly finished and has a loop handle that has been seen to be either horizontal, vertical or diagonal to the face, although horizontal handles are the most common ones. Some of them are plain but others have traces of a thin coat of stucco painted in yellow, red, back, brown, green, and pink.[8]

In Cholula figurines mostly represent the god Tlaloc. There have been at least six molds found that were used to produce Tlaloc figurines in the collection from the campus of the Universidad de las Américas and each one exhibits differences in size, proportion, and the detailed elements of its portrait.[8]

Notes

- Evans, Susan Toby (2001). Archaeology of ancient Mexico and Central America, an Encyclopedia. New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc. pp. 139–141.

- Pohl, John. "John Pohl's MESOAMERICA MAJOR ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES: PreClassic to PostClassic CHOLULA (circa CE 100-1521)". Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. Retrieved October 15, 2013.

- McCafferty, Sharisse D.; McCafferty, Geoffrey (2000). "Textile Production in Postclassic Cholula, Mexico". Ancient Mesoamerica. 11: 39–54. doi:10.1017/s0956536100111071.

- Coe, Michael D. (2008). Mexico: from the Olmecs to the Aztecs. New York: Thames & Hudson. p. 140.

- "Spaniards Attack Cholulans From Díaz del Castillo, Vol. 2, Chapter 83". American Historical Association. Archived from the original on 2012-10-08. Retrieved 2012-04-08.

- Coe, Michael D. (2008). Mexico: from the Olmecs to the Aztecs. London. p. 121.

- Snow, Dean R. (2010). Archaeology of Native North America. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. p. 157.

- Uruñuela, Gabriela; Patricia Plunket; Gilda Hernández; Juan Albaitero (March 1997). "Biconical God Figurines from Cholula and the Codex Borgia". Latin American Antiquity. 8 (1): 65. doi:10.2307/971593.

References

- Coe, Michael D.; Koontz, Rex (2013). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-29076-7.

- Evans, Susan Toby; Webster, David L. (2001). Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: An Encyclopedia. New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc.

- Davies, Nigel (1982). The Ancient Kingdoms of Mexico. Penguin Books.

- Pohl, John. "John Pohl's MESOAMERICA MAJOR ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES: PreClassic to PostClassic CHOLULA (circa A.D. 100-1521)". Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc. Retrieved 2012-04-08.

- Snow, Dean R. (2010). Archaeology of Native North America. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. p. 157.

- McCafferty, Sharisse D.; McCafferty, Geoffrey (2000). "Textile Production in Postclassic Cholula, Mexico". Ancient Mesoamerica. 11: 39–54. doi:10.1017/s0956536100111071.

- Diaz del Castillo. "Spaniards Attack Cholulans From Díaz del Castillo, Vol. 2, Chapter 83". American Historical Association. Archived from the original on 2012-10-08. Retrieved 2012-04-08.

External links

- Cholula photos, Tour By Mexico

- Cholula, Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies

- A historic map of Cholula from 1581