Muisca calendar

The Muisca calendar was a lunisolar calendar used by the Muisca. The calendar was composed of a complex combination of months and three types of years were used; rural years (according to Pedro Simón, Chibcha: chocan),[1] holy years (Duquesne, Spanish: acrótomo),[2] and common years (Duquesne, Chibcha: zocam).[3] Each month consisted of thirty days and the common year of twenty months, as twenty was the 'perfect' number of the Muisca, representing the total of extremeties; fingers and toes. The rural year usually contained twelve months, but one leap month was added. This month (Spanish: mes sordo; "deaf month") represented a month of rest. The holy year completed the full cycle with 37 months.

|

| Part of a series on |

| Muisca culture |

|---|

| Topics |

| Geography |

| The Salt People |

| Main neighbours |

| History and timeline |

The Muisca were one of the four advanced civilizations of the Americas before the arrival of the Europeans[4] inhabiting the central highlands of the Colombian Andes (Altiplano Cundiboyacense) and as the other three (Aztec, Mayas and Incas) they had their own calendar, arranged by Bochica.[5] Important Muisca scholars who have brought the knowledge of the Muisca calendar and their counting system to Europe were Spanish conquistador Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada who encountered Muisca territory in 1537, Bernardo de Lugo (1619),[6] Pedro Simón in the 17th century and Alexander von Humboldt and José Domingo Duquesne published their findings in the late 18th and early 19th century.[5][7][8][9] At the end of the 19th century, Vicente Restrepo wrote a critical review of the work of Duquesne.[10]

21st century researchers are Javier Ocampo López[11] and Manuel Arturo Izquierdo Peña, anthropologist who published his MSc. thesis on the Muisca calendar.[12]

Numeral system

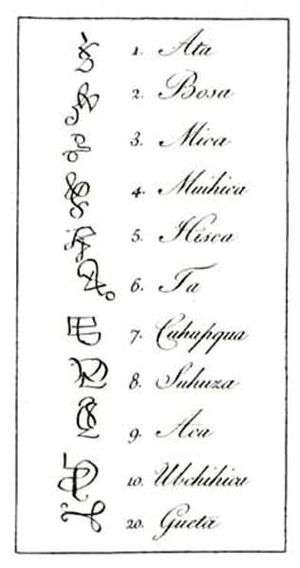

The Muisca used a decimal counting system and counted with their fingers. Their system went from 1 to 10 and for higher numerations they used the prefix quihicha or qhicha, which means "foot" in their Chibcha language Muysccubun. Eleven became thus "foot one", twelve "foot two", etc. As in the other pre-Columbian civilizations, the number 20 was special. It was the total number of all body extremities; fingers and toes. The Muisca used two forms to express twenty: "foot ten"; quihícha ubchihica or their exclusive word gueta, derived from gue, which means "house". Numbers between 20 and 30 were counted gueta asaqui ata ("twenty plus one"; 21), gueta asaqui ubchihica ("twenty plus ten"; 30). Larger numbers were counted as multiples of twenty; gue-bosa ("20 times 2"; 40), gue-hisca ("20 times 5"; 100).[5] The Muisca script consisted of hieroglyphs, only used for numerals.[13] There is doubt as to the whether or not the document reporting the existence of this hieroglyphic numerical system is to be believed, as it is only primary source attesting this system.[14]

Numbers 1 to 10 and 20

| Number | Humboldt, 1807[5] | De Lugo, 1619[6] | Muisca hieroglyphs |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ata |  | |

| 2 | bozha / bosa | boʒha | |

| 3 | mica | ||

| 4 | mhuyca / muyhica | mhuɣcâ | |

| 5 | hicsca / hisca | hɣcſcâ | |

| 6 | ta | ||

| 7 | qhupqa / cuhupqua | qhûpqâ | |

| 8 | shuzha / suhuza | shûʒhâ | |

| 9 | aca | ||

| 10 | hubchibica / ubchihica | hubchìhicâ | |

| 20 | quihicha ubchihica gueta |

qhicħâ hubchìhicâ guêata | |

Higher numbers

To name the days and months the Muisca did not use numbers higher than 10, except gueta for their perfect number of 20. Instead, they named the 11th month just like the 1st; ata. Same for the other months and days until 19. That rather confusing system made it difficult to distinguish the 21st month from the 1st or 11th, but their naming of the three different years solved this.

Time calculation

The calculation of time in the Muisca calendar was a complex combination of different time spans, which describe periods that extends from weeks to years, centuries and even higher time spans. The day was defined by the daily solar cycle, whereas the month was defined, depending on the context, by both the synodical and the sidereal lunar cycles.[15] Different scholars have described variation of weeks (3, 10 or 15 days), years (rural, common and holy) centuries (common and holy) and eventually, higher periods of time as the Bxogonoa.

Days

The Muisca called "day" sua (the word for "Sun") and "night" za. The priests had divided a day in four parts:[16] suamena (from sunrise to mid-day), suameca (from mid-day to sunset), zasca was the time from sunset to midnight and chaqüi the time from midnight to sunrise.[17]

Weeks and months

About the configuration of the weeks in the Muisca calendar different chroniclers show various subdivisions. Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada describes a month of 30 days comprising three weeks of ten days,[18] Pedro Simón stated the Muisca had a month composed of two weeks of 15 days[19] and José Domingo Duquesne and Javier Ocampo López wrote the Muisca week had just three days, with ten weeks in a month.[19][20] Izquierdo suggests, however, that the concept for a standardized week was alien to the Muisca indeed, who instead organized the days of the month in terms of the varying activities of their social life.[21]

The Muisca, like the Incas in the Central Andes, very probably took notice of the difference between the synodic month (29 days, 12 hours, 44 minutes); the time between two full Moons, and the sidereal month (27 days, 7 hours, 43 minutes); the time it takes for the Moon to reach the same position with respect to the stars.[15]

Years

The Muisca word for year was zocam, which is always used in combination with a number: zocam ata, "year one", zocam bosa, "year two". Following the works of Duquesne, three types of years were used; Rural years, Common years and Priest's years. The years were composed of different sets of months:

- The Rural Year contained 12 synodic months,

- The Priest's Year composed of 37 synodic months, or 12 + 12 + 13 synodic months (the 13th was a leap month, called "deaf" in Spanish),

- The Common Year composed by 20 months, making a full common Muisca year 600 days or 1.64 times a Gregorian year.[8][22] Izquierdo suggests, however, that this year, unlike the Rural and the Priest's years, was based on the sidereal lunar cycle.[23]

Centuries and higher time spans

According to Duquesne, the Muisca used devised a Priest's Century by scaling up The Priest's Year by gueta (20 times 37 months; 740) which approximately equals 60 Gregorian years.[22][24] The same scholar referred to a Common Century (siglo vulgar) comprising 20 times 20 months.[25] Pedro Simón's differences on the accounts of the mythical arrival of Bochica to the Muisca territory brings clues about the nature of the Priest's Century. According Simón, the century (edad) corresponded to 70 (setenta) years, however, Izquierdo suggests that such a value is typo of 60 (sesenta) years, which is a value that better matches the entire calendar's description.[26] Besides the centuries, the chronicles describe further periods of time: the Astronomical Revolution as called by Duquesne, corresponds to 5 Priest's Years or 185 synodical months, thus comprising a quarter of a Priest's Century. Simón describes also an additional time period named the Bxogonoa which corresponds to 5 Priest's Centuries. Again, both Duquesne and Humboldt describe another time span, the Dream of Bochica which accounted for 100 Priest's Centuries, which correspond to 2000 Priest's Years or 5978 Gregorian years.[27] After the analysis of all these many units of time, Izquierdo proposed a hierarchical organization where these periods are the product of multiplying the months of The Priest's Year by both 5 and the first three powers of 20:[27]

| First order | Second order | Third order | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time period | Synodical months | Time period | Synodical months | Time period | Synodical months |

| Priest's year | Priest's Century | Arrival of Bochica | |||

| Astronomical Revolution | Bxogonoa | Dream of Bochica | |||

Calendar

To name the months, the Muisca did not use higher numbers than 10, except for the 20th month, indicated with the 'perfect' number gueta. The calendar table shows the different sets of zocam ("years") with the sets of months, as published by Alexander von Humboldt.[8] The meaning of each month has been described by Duquesne in 1795 and summarized by Izquierdo Peña in 2009.[28]

| Gregorian year 12 months |

Month 30 days |

Rural year 12 or 13 months |

Common year 20 months |

Holy year 37 months |

Symbols; "meanings" - activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Ata | Ata | Ata | Jumping toad; "start of the year" |

| 2 | Bosa | Nose and nostrils | |||

| 3 | Mica | Open eyes and nose; "to look for", "to find" | |||

| 4 | Muyhica | Two closed eyes; "black thing", "to grow" | |||

| 5 | Hisca | Two fingers together; "green thing", "to enjoy" | |||

| 6 | Ta | Stick and cord; "sowing" - harvest | |||

| 7 | Cuhupqua | Two ears covered; "deaf person" | |||

| 8 | Suhuza | Tail; "to spread" | |||

| 9 | Aca | Toad with tail connected to other toad; "the goods" | |||

| 10 | Ubchihica | Ear; "shining Moon", "to paint" | |||

| 11 | Ata | ||||

| 12 | Bosa | ||||

| 2 | 13 | Bosa | Mica | ||

| 14 | Muyhica | ||||

| 15 | Hisca | ||||

| 16 | Ta | ||||

| 17 | Cuhupqua | ||||

| 18 | Suhuza | harvest | |||

| 19 | Aca | ||||

| 20 | Gueta | Lying or stretched toad; "sowing field", "to touch" | |||

| 21 | Bosa | Ata | |||

| 22 | Bosa | ||||

| 23 | Mica | ||||

| 24 | Muyhica | ||||

| 3 | 25 | Mica | Hisca | ||

| 26 | Ta | ||||

| 27 | Cuhupqua | ||||

| 28 | Suhuza | ||||

| 29 | Aca | ||||

| 30 | Ubchihica | harvest | |||

| 31 | Ata | ||||

| 32 | Bosa | ||||

| 33 | Mica | ||||

| 34 | Muyhica | ||||

| 35 | Hisca | ||||

| 36 | Ta | Embolismic month | |||

| 4 | 37 | Deaf month | Chuhupqua | End of the holy year; full cycle | |

Celebrations

The Gregorian month of December was a month of celebrations with yearly feasts, especially in Sugamuxi called huan, according to Pedro Simón.[29]

Archeological evidences

The archeological evidence for the Muisca calendar and its use is found in ceramics, textiles, spindles, petroglyphs, sites and stones.[30]

Important findings are:

- Choachí Stone, found in the first half of the 20th century in the municipality of Choachí may represent a calculator to convert the different parts of the complex Muisca calendar[31][32]

- Ceremonial flute (fotuto ceremonial), decorated flute made of a marine snail shell, found in Socorro, Santander, located in the Archeology Museum Sogamoso[33]

- Decorated textile, found in Belén, Boyacá and located in the museum of Pasca, regarded as a "Muisca codex"[34]

- El Infiernito, astronomical site of the Muisca near Villa de Leyva[35]

- Jaboque, in this humedal ancient menhirs were found, indicating an astronomical knowledge of the Muisca[36]

References

- Izquierdo Peña, 2014, 11:48

- Izquierdo Peña, 2014, 13:25

- Izquierdo Peña, 2014, 12:40

- Ocampo López, 2007, Ch.V, p.188

- Humboldt, 1807, Part 1

- (in Spanish) 1619 - Muisca numbers according to Bernardo de Lugo - accessed 29-04-2016

- Humboldt, 1807, Part 2

- Humboldt, 1807, Part 3

- Duquesne, 1795

- Restrepo, 1892

- Ocampo López, 2007, Ch. V, p.228-229

- Izquierdo Peña, 2009, p.1-170

- Izquierdo Peña, 2009

- Izquierdo Peña, 2009

- Izquierdo Peña, 2014, 56:35

- (in Spanish) Calendario lunar de los muiscas - accessed 28-04-2016

- (in Spanish) Calendario muisca - Pueblos Originarios - accessed 28-04-2016

- Izquierdo Peña, 2009, p.32

- Izquierdo Peña, 2009, p.33

- Ocampo López, 2007, Ch.V, p.228

- Izquierdo Peña, 2011, p.110

- Duquesne, 1795, p.3

- Izquierdo Peña, 2011, p.115

- Izquierdo Peña, 2014, 20:35

- Izquierdo Peña, 2014, 22:05

- Izquierdo Peña, 2014, 50:25

- Izquierdo Peña, 2011, p.114

- Izquierdo Peña, 2009, p.30

- Izquierdo Peña, 2014, 18:00

- Izquierdo Peña, 2014, 1:17:25

- Izquierdo Peña, 2009, p.86

- Izquierdo Peña, 2014, 1:09:00

- Izquierdo Peña, 2014, 1:09:55

- Izquierdo Peña, 2014, 1:13:00

- Santos, 2015

- Jaboque Petroform Menhirs - accessed 05-05-2016

Bibliography

- Acosta, Joaquín. 1848. Compendio histórico del descubrimiento y colonización de la Nueva Granada en el siglo décimo sexto, 1-460. Beau Press. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Duquesne, José Domingo. 1795. Disertación sobre el calendario de los muyscas, indios naturales de este Nuevo Reino de Granada - Dissertation about the Muisca calendar, indigenous people of this New Kingdom of Granada, 1-17. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Humboldt, Alexander von. 1807. VI.Sitios de las Cordilleras y monumentos de los pueblos indígenas de América - Calendario de los indios muiscas - Parte 1 - Views of the Cordilleras and Monuments of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas - Muisca calendar - Part 1. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Humboldt, Alexander von. 1807. VI.Sitios de las Cordilleras y monumentos de los pueblos indígenas de América - Calendario de los indios muiscas - Parte 2. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Humboldt, Alexander von. 1807. VI.Sitios de las Cordilleras y monumentos de los pueblos indígenas de América - Calendario de los indios muiscas - Parte 3. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Izquierdo Peña, Manuel Arturo. 2014. Calendario Muisca - Muisca calendar. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Izquierdo Peña, Manuel Arturo. 2009. The Muisca Calendar: An approximation to the timekeeping system of the ancient native people of the northeastern Andes of Colombia (PhD), 1-170. Université de Montréal. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Ocampo López, Javier. 2007. Grandes culturas indígenas de América - Great indigenous cultures of the Americas, 1–238. Plaza & Janes Editores Colombia S.A..

- Restrepo, Vicente. 1892. Crítica de los trabajos arqueológicos del Dr. José Domingo Duquesne - Review of the archeological works of Dr. José Domingo Duquesne, 1–44. Accessed 2016-07-08.

- Santos, Gisele. 2015. El Infiernito: sacred site of the Muisca civilization of Colombia. Ancient Origins. Accessed 2016-07-08.