Mezcala culture

The Mezcala culture (sometimes referred to as the Balsas culture) is the name given to a Mesoamerican culture that was based in the Guerrero state of southwestern Mexico,[1] in the upper Balsas River region.[2] The culture is poorly understood but is believed to have developed during the Middle and Late Preclassic periods of Mesoamerican chronology,[1] between 700 and 200 BC.[2] The culture continued into the Classic period (c.250-650 AD) when it coexisted with the great metropolis of Teotihuacan.[3]

Archaeologists have studied the culture through limited controlled excavations, the examination of looted artifacts, and the study of Mezcala sculptures found as dedicatory offerings at the Aztec complex of Tenochtitlan.

Archaeological excavations

The Mezcala cultural region has been heavily looted by the local population, as these items have proven desirable on the art market.[4] In terms of its archaeological resources, the present-day state of Guerrero has not seen extensive professional excavations; prehistoric cultures found there are among the least understood in Mexico.[1] Only one Preclassic Mezcala site, Ahuinahuac, has been investigated by archaeologists undertaking controlled excavations.[2] Excavations of Classic period Mezcala sites have taken place at Organera Xochipala and El Mirador.[5] The sculptural style of the Mezcala culture is largely known from looted andesite and serpentine artifacts.[1]

History

Based on excavations in Guerrero, examination of looted artifacts, and excavation of Mezcala artifacts at Teotihuacan, archaeologists have given the name "Mezcala culture" to a Mesoamerican culture that was based in the present-day Guerrero state of southwestern Mexico,[1] in the upper Balsas River region.[2] Archaeologists believe that the culture developed during the Middle and Late Preclassic periods of Mesoamerican chronology,[1] between 700 and 200 BC.[2] and continued into the Classic period (c.250-650 AD). At this time, the great metropolis of Teotihuacan developed to the north in the Valley of Mexico.[3]

In the Mezcala area, Teotihuacan influence is pervasive. At the same time, there was also considerable influence going the other way, from the Mezcala area to Teotihuacan.[6]

Anthropologists characterized the western societies as chiefdoms, at a time when states rose in Central Mexico. Unlike other areas of western Mexico, the Guerrero tradition in ceramics and site planning shows influence from Central Mexico. For instance, settlements along the Balsas River had pyramids, central plazas and ball courts.[7]

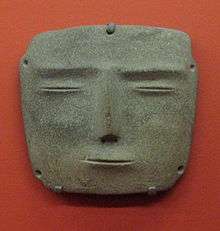

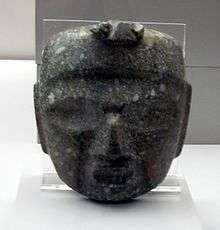

The later Aztecs apparently excavated Mezcala sculptures and valued them, since the works have been found among the dedicatory offerings excavated at the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan,[8] built in the 14th and 15th centuries. These included over fifty-six masks and ninety-eight figurines.[9] Twenty-six of the figurines were divided equally between two stone boxes and arranged in south-facing rows.[10]

Sculpture

Mezcala-style sculpture is characterised by abstract facial features, suggested by lines and differences in texture.[3] The sculptural style of the Mezcala culture may have been influenced by the Olmecs. In turn, it may have influenced the development of sculpture at the Classic-period metropolis of Teotihuacan in the Valley of Mexico.[1]

See also

Notes

- Coe and Koontz 1962, 2002, p.55.

- López Austin and López Luján 2001, p.88.

- Matos Moctezuma 2002c, p.465.

- López Austin and López Luján 2001, p.88. Coe and Koontz 1962, 2002, p.55.

- López Austin and López Luján 2001, p. 124

- Evans and Webster 2013, p.320.

- López Austin and López Luján 2001, pp.123-124

- Coe and Koontz 1962, 2002, pp.55-56.

- Matos Moctezuma 2002b, p.460.

- Matos Moctezuma 2002a, p.53.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mezcala culture. |

- Coe, Michael D.; Rex Koontz (2002) [1962]. Mexico: from the Olmecs to the Aztecs (5th, revised and enlarged ed.). London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-28346-X. OCLC 50131575.

- Evans, Susan Toby; David L. Webster (eds.). Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 1136801855.

- López Austin, Alfredo; Leonardo López Luján (2001) [1996]. Bernard R. Ortiz de Montellano (ed.). Mexico's Indigenous Past. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-3214-0. OCLC 45879556.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo (2002a). "The Templo Mayor, the Great Temple of the Aztecs". In Eduardo Matos Moctezuma and Felipe Solis Olguín (ed.). Aztecs. London: Royal Academy of Arts. pp. 48–55. ISBN 1-90397-322-8. OCLC 56096386.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo (2002b). "239: Tlaloc". In Eduardo Matos Moctezuma and Felipe Solis Olguín (ed.). Aztecs. London: Royal Academy of Arts. pp. 459–460. ISBN 1-90397-322-8. OCLC 56096386.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo (2002c). "261: Mask". In Eduardo Matos Moctezuma and Felipe Solis Olguín (ed.). Aztecs. London: Royal Academy of Arts. p. 465. ISBN 1-90397-322-8. OCLC 56096386.

Further reading

- Reyna Robles, Rosa María (2003). La Organera-Xochipala: Un sitio del Epiclásico en la Región Mezcala de Guerrero (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. ISBN 9789703503339.

- Reyna Robles, Rosa María (November–December 2006). "La Organera-Xochipala, Guerrero". Arqueología Mexicana (in Spanish). Mexico City, Mexico: Editorial Raíces. XIV (82). Archived from the original on 2015-04-14.