Moche culture

The Moche civilization (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈmotʃe]; alternatively, the Mochica culture or the Early, Pre- or Proto-Chimú) flourished in northern Peru with its capital near present-day Moche, Trujillo, Peru[1][2] from about 100 to 700 AD during the Regional Development Epoch. While this issue is the subject of some debate, many scholars contend that the Moche were not politically organized as a monolithic empire or state. Rather, they were likely a group of autonomous polities that shared a common culture, as seen in the rich iconography and monumental architecture that survives today.

Moche culture Moche | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100–700 | |||||||||

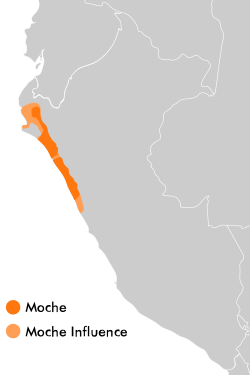

A map of Moche cultural influence | |||||||||

| Status | Culturally united independent polities | ||||||||

| Capital | Moche[1] | ||||||||

| Common languages | Mochica | ||||||||

| Religion | Polytheist | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early Intermediate | ||||||||

• Established | 100 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 700 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Peru |

.svg.png) |

| By chronology |

| By political entity |

| By topic |

|

|

Background

Moche society was agriculturally based, with a significant level of investment in the construction of a network of irrigation canals for the diversion of river water to supply their crops. Their culture was sophisticated; and their artifacts express their lives, with detailed scenes of hunting, fishing, fighting, sacrifice, sexual encounters and elaborate ceremonies. The Moche are particularly noted for their elaborately painted ceramics, gold work, monumental constructions (huacas) and irrigation systems.[3]

Moche history may be broadly divided into three periods – the emergence of the Moche culture in Early Moche (100–300 AD), its expansion and fluorescence during Middle Moche (300–600 AD), and the urban nucleation and subsequent collapse in Late Moche (500–750 AD).[4]

The Salinar culture reigned on the north coast of Peru in 200 BC–200 AD. According to some scholars, this was a short transition period between the Cupisnique and the Moche cultures.[5]

There is considerable parallelism between Moche and Cupisnique iconography and ceramic designs, including the iconography of the 'Spider god'.

Moche cultural sphere

The Moche cultural sphere is centered on several valleys on the north coast of Peru in regions La Libertad, Lambayeque, Jequetepeque, Chicama, Moche, Virú, Chao, Santa, and Nepena[6] and occupied 250 miles of desert coastline and up to 50 miles inland.[7]

The Huaca del Sol, a pyramidal adobe structure on the Rio Moche, was the largest pre-Columbian structure in Peru, but it was partly destroyed when Spanish Conquistadors looted its graves for gold in the 16th century. The nearby Huaca de la Luna is better preserved. Its interior walls contain many colorful murals with complex iconography. The site has been under professional archaeological excavation since the early 1990s.

Other major Moche sites include Sipan, Loma Negra, Dos Cabezas, Pacatnamu, the El Brujo complex, Mocollope, Cerro Mayal, Galindo, Huanchaco, and Pañamarka.

Their adobe huacas have been mostly destroyed by looters and natural forces over the last 1300 years. The surviving ones show that the coloring of their murals was very vibrant. Moche

Southern and Northern Moche

Two distinct regions of the Moche civilization have been identified, Southern and Northern Moche, with each area probably corresponding to a different political entity.[8]

The Southern Moche region, believed to be the heartland of the culture, originally comprised the Chicama and Moche valleys, and was first described by Rafael Larco Hoyle.[8] The Huaca del Sol-Huaca de la Luna site was probably the capital of this region.[8]

The Northern Moche region includes three valley systems:[8]

- The upper Piura Valley, around the Vicús culture region

- The lower Lambayeque Valley system, consisting of three rivers: La Leche, Reque and Zaña

- The lower Jequetepeque Valley system

The Piura was fully part of the Moche phenomenon only for a short time—during its Early Moche, or Early Moche-Vicús phase—and then developed independently.[8]

It appears that there was a lot of independent development among these various Moche centres (except the eastern regions). They all likely had ruling dynasties of their own, related to each other. Centralized control of the whole Moche area may have taken place from time to time, but appears infrequent.[8]

Pampa Grande, in the Lambayeque Valley, on the shore of the Chancay River, became one of the largest Moche sites anywhere, and occupied the area of more than 400 ha. It was prominent in the Moche V period (600–700 AD), and features an abundance of Moche V ceramics.

The site was laid out and built in a short period of time, and has an enormous ceremonial complex. It includes Huaca Fortaleza, which is the tallest ceremonial platform in Peru.[8]

San Jose de Moro is another northern site in the Jequetepeque valley. It was prominent in the Middle and Late Moche Periods (400–850 AD). Numerous Moche tombs have been excavated here, including several burials containing high status female individuals. These women were depicted in Moche iconography as the Priestess.

Material culture

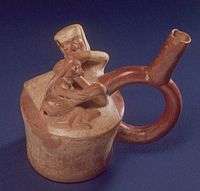

Ceramics

Moche pottery is some of the most varied in the world. The use of mold technology is evident. This would have enabled the mass production of certain forms. But Moche ceramics vary widely in shape and theme, with most important social activities documented in pottery, including war, metalwork, weaving and sex.

Traditional north coast Peruvian ceramic art uses a limited palette, relying primarily on red and white; fineline painting, fully modeled clay, veristic figures, and stirrup spouts. Moche ceramics created between 150–800 CE epitomize this style. Moche pots have been found not just at major north coast archaeological sites, such as Huaca de la luna, Huaca del sol, and Sipan, but also at small villages and unrecorded burial sites as well.

At least 500 Moche ceramics have sexual themes. The most frequently depicted act is anal sex, with scenes of vaginal penetration being very rare. Most pairs are heterosexual, with carefully carved genitalia to show that the anus, rather than the vagina, is being penetrated. Often, an infant is depicted breastfeeding while the couple has sex. Fellatio is sometimes represented, but cunnilingus is absent. Some depict male skeletons masturbating, or being masturbated by living women.[9]

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

Because irrigation was the source of wealth and foundation of the empire, the Moche culture emphasized the importance of circulation and flow. Expanding upon this, Moche artwork frequently depicted the passage of fluids, particularly life fluids through vulnerable human orifices. There are countless images of defeated warriors losing life fluids through their nose, or helpless victims getting their eyes torn out by birds or captors. Images of captive sex-slaves with gaping orifices and leaking fluids portray extreme exposure, humiliation, and a loss of power.

The coloration of Moche pottery is often simple, with yellowish cream and rich red used almost exclusively on elite pieces. White and black are rarely used. The Moche are known for their portraiture pottery. The pottery portraits created by the Moche appear to represent actual individuals. Many of the portraits are of individuals with physical disfigurements or genetic defects.

The realistic detail in Moche ceramics may have helped them serve as didactic models. Older generations could pass down general knowledge about reciprocity and embodiment to younger generations through such portrayals. The sex pots could teach about procreation, sexual pleasure, cultural and social norms, a sort of immortality, and transfer of life and souls, transformation, and the relationship between the two cyclical views of nature and life.[12]

Textiles

The Moche wove textiles, mostly using wool from vicuña and alpaca. Although there are few surviving examples of this, descendants of the Moche people have strong weaving traditions.

Metalwork

The Moche discovered both electrochemical replacement plating and depletion gilding, which they used to cover copper crafts found at Loma Negra in thin layers of gold or silver. Modern attempts were able to recreate a similar chemical plating process using boiling water and salts found naturally in the area. [13]

Gallery

Moche portrait vessel,

Moche portrait vessel,

Musée du quai Branly, Paris Resting deer,

Resting deer,

Larco Museum Collection, Lima- Alpaca wool tapestry (CE 600–900), Lombards Museum

Earplugs of gold inlaid with precious stones

Earplugs of gold inlaid with precious stones

Ceramic depicting anal sex

Ceramic depicting anal sex Moche warrior pot, British Museum, London

Moche warrior pot, British Museum, London Crescent-shaped ornament with bat, CE 1–300 Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn

Crescent-shaped ornament with bat, CE 1–300 Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn Copper alloy mask with shell, CE 1–600 Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Copper alloy mask with shell, CE 1–600 Walters Art Museum, Baltimore_with_Removable_Figural_Handle_-_Walters_543078.jpg) Copper knife with removable figural handle, CE 50–800 Walters Art Museum, Baltimore

Copper knife with removable figural handle, CE 50–800 Walters Art Museum, Baltimore Moche headdress with feline ornamentations, CE 400 Larco Museum, Lima

Moche headdress with feline ornamentations, CE 400 Larco Museum, Lima Gold Moche necklace with feline faces, Larco Museum, Lima

Gold Moche necklace with feline faces, Larco Museum, Lima Gold Moche whistle with turquoise depicting a warrior, CE 1–800 Larco Museum, Lima

Gold Moche whistle with turquoise depicting a warrior, CE 1–800 Larco Museum, Lima Bronze and shell Moche mask depicting the hero Ai Apaec

Bronze and shell Moche mask depicting the hero Ai Apaec_MET_1987.394.150.jpg) Copper ceremonial knife (Tumi), CE 3rd – 7th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Copper ceremonial knife (Tumi), CE 3rd – 7th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Religion

Both iconography and the finds of human skeletons in ritual contexts seem to indicate that human sacrifice played a significant part in Moche religious practices. These rites appear to have involved the elite as key actors in a spectacle of costumed participants, monumental settings and possibly the ritual consumption of blood. The tumi was a crescent-shaped metal knife used in sacrifices. While some scholars, such as Christopher B. Donnan and Izumi Shimada, argue that the sacrificial victims were the losers of ritual battles among local elites, others, such as John Verano and Richard Sutter, suggest that the sacrificial victims were warriors captured in territorial battles between the Moche and other nearby societies. Excavations in plazas near Moche huacas have found groups of people sacrificed together and the skeletons of young men deliberately excarnated, perhaps for temple displays.[14]

The Moche may have also held and tortured the victims for several weeks before sacrificing them, with the intent of deliberately drawing blood. Verano believes that some parts of the victim may have been eaten as well in ritual cannibalism.[14] The sacrifices may have been associated with rites of ancestral renewal and agricultural fertility. Moche iconography features a figure which scholars have nicknamed the "Decapitator"; it is frequently depicted as a spider, but sometimes as a winged creature or a sea monster: together all three features symbolize land, water and air. When the body is included, the figure is usually shown with one arm holding a knife and another holding a severed head by the hair; it has also been depicted as "a human figure with a tiger's mouth and snarling fangs".[15] The "Decapitator" is thought to have figured prominently in the beliefs surrounding the practice of sacrifice.

Collapse

There are several theories as to what caused the demise of the Moche political structure. Some scholars have emphasised the role of environmental change. Studies of ice cores drilled from glaciers in the Andes reveal climatic events between 536 and 594 AD, possibly a super El Niño, that resulted in 30 years of intense rain and flooding followed by 30 years of drought, part of the aftermath of the climate changes of 535–536.[16] These weather events could have disrupted the Moche way of life and shattered their faith in their religion, which had promised stable weather through sacrifices.

Other evidence demonstrates that these events did not cause the final Moche demise. Moche polities survived beyond 650 AD in the Jequetepeque Valley and the Moche Valleys. For instance, in the Jequetepeque Valley, later settlements are characterized by fortifications and defensive works. While there is no evidence of a foreign invasion, as many scholars have suggested in the past (i.e. a Huari invasion), the defensive works suggest social unrest, possibly the result of climatic changes, as factions fought for control over increasingly scarce resources.[17]

Links with other cultures

Chronologically, the Moche was an Early Intermediate Period culture, which was preceded by the Chavín horizon, as well as the Cupisnique, and succeeded by the Huari and Chimú. The Moche co-existed with the Ica-Nazca culture in the south. They are thought to have had some limited contact with the Ica-Nazca because they later mined guano for fertilizer and may have traded with northerners. Moche pottery has been found near Ica, but no Ica-Nazca pottery has been found in Moche territory.

The coastal Moche culture also co-existed (or overlapped in time) with the slightly earlier Recuay culture in the highlands. Some Moche iconographic motifs can be traced to Recuay design elements.

The Moche also interacted with the neighbouring Virú culture. Eventually, by 700 CE, they established control over the Viru.

Archaeological discoveries

In 1899 and 1900, Max Uhle was the first archaeologist to excavate a Moche site, Huaca de la Luna which is where the architectural complex that is known as Huacas de Moche (Pyramids of Moche) is located in the Moche Valley. The name of this architectural complex is where the name of the Moche site and culture came from.[18]

Excavations in 1938 and 1939 by Rafael Larco Hoyle saw the development of the first interpretations of Moche culture, ranking the Moche as being "high on the list of advanced societies" as a civilization. He listed traits of the Moche culture such as "exquisite artworks" and the "creation of large scale facilities and public works" as a testament to this ranking.[18]

Although arguably the most significant event which shaped Moche archaeological research was the Virú Valley Project beginning in 1946 and was led by Willian Duncan Strong and Wendell Bennett. Their stratigraphic excavations in Virú showed an earlier ceramic style, which is known as Gallinazo which appeared to have “abruptly ended”.[18]

In 1987, archaeologists, alerted by the local police, discovered the first intact Moche tomb at Sipán in northern Peru. Inside the tomb, which was carbon dated to about 300 AD, the archaeologists found the mummified remains of a high ranking male, the Lord of Sipán. Also in the tomb were the remains of six other individuals, several animals, and a large variety of ornamental and functional items, many of which were made of gold, silver, and other valuable materials. Continuing excavations of the site have yielded thirteen additional tombs.

In 2005, a mummified Moche woman known as the Lady of Cao was discovered at the Huaca Cao Viejo, part of the El Brujo archaeological site on the outskirts of present-day Trujillo, Peru. It is the best preserved Moche mummy found to date; the elaborate tomb that housed her had unprecedented decoration. The site archaeologists believe that the tomb had been undisturbed since approximately 450 AD. The tomb contained military and ornamental artifacts, including war clubs and spear throwers. The remains of a garroted teenage girl, probably a servant, was also found in the tomb.[19] News of the discovery was announced by Peruvian and U.S. archaeologists in collaboration with National Geographic in May 2006.[20]

In 2005 an elaborate gold mask thought to depict a sea god, with curving rays radiating from a stone-inlaid feline face, was recovered in London. Experts thought that the artifact may have been looted in the late 1980s from an elite tomb at the Moche site of La Mina. Recovered by Scotland Yard, it was returned to Peru in 2006.[21][22]

In 2013 archaeologists unearthed the eighth of a series of finds of female skeleton that started with the Lady of Cao, together taken as confirmation that the Moche were ruled by a succession of priestesses-queens. According to project director Luis Jaime Castillo, "[the] find makes it clear that women didn't just run rituals in this area but governed here and were queens of Mochica society". No entombed men have been found.[23] This discovery was made at the large archaeological site of San José de Moro, located close to the town of Chepen, in the Sechura Desert of the Jequetepeque Valley, in La Libertad Region, Peru.[24]

See also

- Chimu Empire, heavily influenced inheritors of the Moche

- Cultural periods of Peru

- El Señor de Sipán (the Lord of Sipán)

- Moche Crawling Feline

- Vista Alegre, Trujillo

- Víctor Larco

- Buenos Aires, Trujillo

- Moche, Trujillo (Moche City)

- Viracocha

- Virú culture

References

- Cardenas, Maritza (ed.). "Huacas del Sol y de la Luna – Capital de la Cultura-Mochica" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2012-03-29.

- "Las Huacas del Sol y de a Luna". Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- Beck, Roger B.; Black, Linda; Krieger, Larry S.; Naylor, Phillip C.; Shabaka, Dahia Ibo (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- Bawden, G. (2004). "The Art of Moche Politics". In Silverman, H. (ed.). Andean Archaeology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- The Salinar Culture Tampere Museum

- Castillo Butters, Luis Jaime. "Moche Politics in the Jequetepeque Valley" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-11-23.

- James E. McClellan III; Harold Dorn (2006). Science and Technology in World History: An Introduction. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8360-6. p. 40.

- Butters, L. J. C.; Castillo, S. U. (2007). "The Moche of Northern Perú". In Silverman, H.; Isbell, W. (eds.). Handbook of South American Archaeology (PDF). Blackwell Press.

- Weismantel, M. (2004). "Moche sex pots: Reproduction and temporality in ancient South America" (PDF). American Anthropologist. 106 (3): 495–496. doi:10.1525/aa.2004.106.3.495.

- "Pair of Earflares, Winged Messengers (Moche Culture, Peru)". Smarthistory. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- "Steven Zucker and Dr. Sarahh Scher, Moche Portrait Head Bottle". Smarthistory. May 4, 2016. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- Chapdelaine, Claude; Kennedy, Greg; Uceda Castillo, Santiago (1995). "Neutron activation analysis and local production of ritual ceramics at the Moche site, Peru" (PDF). Bulletin de l'Institut Francais d'Etudes Andines. 24 (2): 183–212. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-12. Retrieved 2012-11-26.

- Lechtman, Heather (June 1984). "Pre-Columbian Surface Metallurgy". Scientific American. 250 (6): 56–63. Retrieved 2020-08-05.

- Popson, Colleen P. (March–April 2002). "Grim Rites of the Moche". Archaeology. 55 (2). Retrieved 2013-05-12.

- "Moche Culture". About Peru History. Archived from the original on 2012-05-20. Retrieved 2012-05-22.

- Keys, David (2000). "The Mud of Hades". Catastrophe: an Investigation into the Origins of the Modern World (1st [American] ed.). New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0345444361.

- Davidson, Nick (2 March 2005). "Lost society tore itself apart". BBC Horizon. Retrieved 2005-05-04.

- Quilter, Jeffrey; Koons, Michele (2012). "The fall of the Moche: a critique of claims for South America's first state" (PDF). Latin American Antiquity. 23 (2): 129 – via Cambridge Core.

- El Brujo and Lady of Cao, go2peru.com

- Norris, Scott (May 16, 2006). "Mummy of Tattooed Woman Discovered in Peru Pyramid". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2006-05-16.

- Lovett, Richard A. (August 18, 2006). "Photo in the News: Looted Peru Headdress Recovered in London". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2010-12-18.

- Vecchio, Rick (September 15, 2006). "Looted gold headdress returned to Peru". Peru This Week. AP. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- Sutherland, Scott (August 29, 2013). "Unearthed Peruvian tomb confirms that women ruled over brutal ancient culture". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- Tomb of a Powerful Moche Priestess-Queen Found in Peru. August 13, 2013 nationalgeographic.com

Further reading

- Alva, Walter (October 1988). "Discovering the New World's Richest Unlooted Tomb". National Geographic. Vol. 174 no. 4. pp. 510–555. ISSN 0027-9358. OCLC 643483454.

- The Art of Precolumbian Gold: The Jan Mitchell Collection. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1985. ISBN 978-0297786276.

- Sawyer, Alan R. (1966). Ancient Peruvian ceramics: the Nathan Cummings collection by Alan R. Sawyer. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Schmid, Martin (2007). Die Mochica an der Nordküste Perus Religion und Kunst einer vorinkaischen andinen Hochkultur (in German). Hamburg: Diplomica-Verl. ISBN 978-3-83666-806-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moche culture. |

- Moche Civilization – Ancient History Encyclopedia

- www.themocheroute.pe

- www.larutamoche.pe

- Map of current Moche city (Wikimapia)

- "A Peruvian Woman Warrior of A.D. 450", New York Times article (17 May 2006) by John Noble Wilford.

- "The Lost Civilisation of Peru", transcript of BBC programme, includes bibliography.

- Gallery of Moche erotic pottery at the Larco Museum.

- El Brujo Archaeological project, website with links to National University of Trujillo, IBM, National Geographic and press reports.

- "Temples of Doom", Discover article (March 1999) by Heather Pringle.

- "The Ulluchu fruit: Blood Rituals and Sacrificial Practices Among the Moche People of Ancient Peru" by Francesco Sammarco.

- "Moche pottery and the practice of war", Horniman Museum video on YouTube channel.

- Moche Iconography, Dumbarton Oaks online resource linking to digitized roll-out drawings of Moche ceramic fineline iconography.