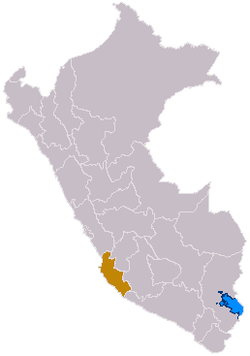

Chincha culture

The Chincha culture consisted of a Native Peruvian people living near the Pacific Ocean in south west Peru. The Chincha Kingdom and their culture flourished in the Late Intermediate Period (900 CE - 1450 CE), also known as the regional states period of pre-Columbian Peru. They became part of the Inca Empire around 1480. They were prominent as sea-going traders and lived in a large and fertile oasis valley. La Centinela is an archaeological ruin associated with the Chincha. It is located near the present-day city of Chincha Alta.

The Chincha disappeared as a people a few decades after the Spanish conquest of Peru, which began in 1532. They died in large numbers from European diseases and the political chaos which accompanied and followed the Spanish invasion.

The Chincha gave their name to the Chinchaysuyo Region, the Chincha Islands, to the animal known as the chinchilla (literally "Little Chincha"), and the city of Chincha Alta. The word "Chinchay" or "Chincha", means "Ocelot" in Quechua.

Setting

Chincha is one of the largest valleys on Pacific Ocean coast of Peru. The valley is about 220 kilometres (140 mi) south of Lima, Peru. The surrounding desert is virtually rainless but the Chincha River flowing down from the Andes waters an extensive valley in the shape of a triangle about 25 kilometres (16 mi) north to south along the coast and extending about 20 kilometres (12 mi) inland. 22,000 hectares (54,000 acres) of land is cultivated in the present day valley and the cultivated land in pre-Columbian times may not have been much less. The Pisco River valley is located 25 kilometres (16 mi) south and is of similar size.[1]

Chincha history

Pre-Chincha era

Human beings have lived along the Peruvian coast for at least 10,000 years. The earliest settlers were probably fishermen, exploiting the rich maritime resources of the Humboldt Current. Irrigation agriculture in river valleys developed later. The first settled communities known in the Chincha valley date from about 800 BCE and belong to the Paracas culture.[2] Later, from 100 BCE to 800 CE the Chincha valley was influenced by the Ica-Nazca culture.[3] The Chincha valley was also influenced, and possibly under the control of the Wari empire, from about 500 CE to 1000 CE.[4]

Between the 9th and 10th centuries, there was a shift in the lifestyle and culture of the coastal inhabitants, with different techniques and styles appearing at the shore region. Some scholars claim that the change was the product of a migratory wave of unknown origin, identifying this culture as the "Pre-Chincha" culture. The rudimentary Pre-Chincha culture relied extensively on fishing and shell gathering.

Chincha era

In the 11th century, the sophisticated and warlike culture known as the Chincha began, possibly the product of a migratory wave from the highlands. The Chincha had developed systems of architecture, agriculture and irrigation. The Chincha culture came to dominate the whole valley. The Chincha worshiped a jaguar god, and believed themselves to be descended from jaguars, who gave them their warlike and dominating tendencies. The Chincha fertilized their fields with dead birds and guano, and this knowledge was passed on to later peoples. The Chincha merchants maintained trade routes by land with herds of camelids used as beasts of burden reaching the Collao (Altiplano) and Cusco. Moreover, the Chincha learned seafaring skills; and new technologies such as raft construction with balsa logs, being the largest capable of carrying twenty people in addition to a large cargo, and the use of the sail, only known by some cultures of Ecuador and Peru in the Pre-Columbian era of the Americas; allowing the Chincha to have extensive maritime trade routes and perhaps traveled as far as Central America by boat (raft). The Chincha sea-going "traders" worshiped a star known to them as Chundri, that may have served for navigation.[5]

The Chincha ruin of La Centinela was one of the first archaeological sites in Peru to be investigated by archaeologists. The site covers more than 75 hectares (190 acres) and consists of two large pyramids, La Centinela and Tambo de Mora, constructed of adobe and serving as the habitations of the leaders of the Chincha people. The surrounding residential area housed artisans of silver, textiles, wood, and ceramics,[6] although, like most pre-Columbian monumental archaeological sites, the main purpose of La Centinela was probably ceremonial rather than residential or commercial.

A network of roads radiated out from La Centinela, running in straight lines, as was the Andean custom. The roads are still visible. The roads extended east and south of la Centinela and led to outlying ceremonial centers and also facilitated the transportation of goods to the Paracas valley to the south and toward the highlands of the Andes which rise about 20 kilometres (12 mi) inland from La Centinela.[7]

According to an early Spanish chronicle, the population of Chincha consisted of 30,000 heads of households, among which were 12,000 agriculturalists, 10,000 fishermen, and 6,000 traders. The numbers suggest a total population of more than 100,000 people under Chincha control, likely in a larger area than the Chincha valley itself. The larger than normal number of fishermen and traders in the population illustrates the commercial nature of the Chincha state and the importance of the sea to their economy.[8] The Chincha like the Chimor and some other Andean cultures used money for commerce.

Chincha and the Incas

Several 16th century Spaniards recorded Chincha history from indigenous Peruvian informants. Although those chronicles are often contradictory, the broad outlines of Chincha history can be discerned. Pedro Cieza de León described Chincha as a "great province, esteemed in ancient times...splendid and grand...so famous throughout Peru as to be feared by many natives." The Chinchas were expanding up and down the coast of Peru and into the Andes highlands at about the same time the Incas were creating their empire in the 14th and 15th centuries.

The Chincha controlled a rich and prominent oracle named Chinchaycamac, probably near La Centinela, which garnered contributions from the Chincha people and others, indicating surpluses of wealth.[9]

The Chinchas were most famous for maritime commerce. Pedro Pizarro said that Atahualpa claimed that the ruler of Chincha controlled 100,000 sea-going rafts, undoubtedly an exaggeration, but illustrating the importance of Chincha and trade.[10] Voyages via balsa raft up and down the Pacific coast from southern Colombia to northern Chile, possibly as far as Mexico, were a long-standing practice, the trade largely being in luxury items such as worked gold and silver and ritually-important Spondylus and Strombus seashells.[11] Some authorities have asserted that the Chincha gained influence and control over much of this maritime trade only late in the fifteenth century. The Incas captured and dismantled the economy of the Chimu in northern Peru about 1470 and gave control of the trade to the Chincha, whose location near the Inca homeland in the highlands made Chincha a convenient entrepot.[12] The source of both the balsa logs for rafts and the Spondylus and Strombus seashells was in Ecuador, 1,400 kilometres (870 mi) to the north, thus strengthening the view that the Chincha had an extensive reach to their trading activities.[13]

The first expedition of the Incas to the Chincha Kingdom was led by the General Capac Yupanqui, Pachacuti's brother, under the rule of the emperor Pachacuti (ruled 1438-71). According to some sources it was an attempt to establish a friendly relationship rather than a conquest, upon the arriving at Chincha, Ccapac Yupanqui said not wanting anything more than the acceptance of Cuzco superiority and gave gifts to the Chincha curacas to show the Inca magnificence. The Chincha had no trouble recognizing the Inca and continue living peacefully in their dominion. The next emperor, Topa Inca Yupanqui (ruled 1471-93) brought the Chincha Kingdom into a true territorial annexation to the empire, but the rulers of Chincha retained much of their political and economic autonomy and their traditional leadership. The Chincha king was required to spend several months each year attending the court of the Inca emperor, although he was given the honors of the highest Inca nobles.[14]

The lord of Chincha was the only person in the Atahualpa's entourage carried on a litter at the meeting with the Spanish. In the Inca culture, the use of a litter in presence of the Sapa Inca was an outstanding honor. The Chincha possibly supported the Atahualpa's faction at the Inca civil war, Atahualpa said that the lord of Chincha was his friend and the greatest lord of the lowlands. The Chincha lord was initially mistaken for Atahualpa because of his displayed wealth at the meeting with Francisco Pizarro, and then killed in the battle of Cajamarca in 1532 in which the emperor Atahualpa was captured by the Spaniards.

Spanish rule

The Spanish first appeared in the Chincha valley in 1534 and a Dominican Roman Catholic mission was founded by 1542. With the arrival of the Spaniards, the population of Chincha declined precipitously, mostly due to European diseases and political turmoil. Demographers have estimated a 99 percent decline in population in the first 85 years of Spanish rule. Chincha never regained its earlier prominence.[15]

See also

Other reading

- Caceres Macedo, Justo. Prehispanic Cultures of Peru. Peruvian Natural History Museum, 1985.

- Rostworowski de Diez Canseco, María. History of the Inca Realm. Cambridge University Press, 1999.

References

- Wallace, Dwight T. (1991), "The Chincha roads: economics and symbolism," in Ancient road networks and settlement hierarchies in the New World edited by Charles D. Trombold, New YorK: Cambridge University Press, p. 256; Google Earth

- Stanish, Charles, Tantalean, Henry, Nigra, Benjamin T., and Griffin, Laura (2014), "A 2,300-year-old architectural and astronomical complex in the Chincha Valley, Peru", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Vol. 111, No. 20, p. 7218

- Prouix, Donald A. (2007), "The Nasca Culture: An Introduction," University of Massachusetts, P. 5, http://people.umass.edu/proulx/online_pubs/Nasca_Overview_Zurich.pdf, accessed 8 August 2016

- Bergh, Susan and Lumbreras, Luis Guillermo (2012), Lords of the Ancient Andes, London: Thames & Hudson, p. 2 (cover)

- Canseco, Maria Rostworowski de Diez (1999). History of the Inca Realm. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521637596.

- Tavero Vega, Lizardo, "La Centinela", http://www.arqueologiadelperu.com.ar/lacentinela.htm, accessed 12 August 2016

- Wallace, pp. 253-255

- Rostworowski de Diez Canseco, Maria (1999), History of the Inca Realm, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 205–206

- Nigra, Ben, Jones, Terrah, Bongers, Jacob, Stanish, Charles, Tantalean, Henry and Perez, Kelita (2014), "The Chincha Kingdom: The Archaeology and Ethnohistory of the Late Intermediate Period South Coast, Peru," Backdirt 2014, p. 39, http://ioa.ucla.edu/sites/default/files/backdirt2014_full_lr_update.pdf, accessed 18 August 2016

- Nigra et al, p. 40

- Dewan, Leslie and Hosler, Dorothy (2008), "Ancient Maritime Trade on Balsa Rafts: An Engineering Analysis," Journal of Archaeological Research, Vol. 64, pp. 19–20

- Sandweiss, Daniel H. and Reid, David A. (2015), "Negotiated Subjugation: Maritime Trade and the Incorporation of Chincha into the Inca Empire", The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology, Vol. 0, Issue 0, http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15564894.2015.1105885, accessed 18 August 2016

- Emanuel, Jeff (2012), "Crown Jewel of the Fleet: Design, Construction, and Use of the Seagoing Balsas of the Pre-Columbian Andean Coast," in Proceedings of the 13th International Symposium on Boats and Ship Archaeology (ISBSA 13), Amsterdam, Netherlands, 8–12 October 2012, http://scholar.harvard.edu/emanuel/mbian-Balsa_ISBSA-13, accessed 2 August 2016

- Nigra et al, pp. 39-40; Sandweiss, Daniel H. (1992), The Archaeology of Chincha Fishermen: Specialization and Status in Inka Peru, Bulletin of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, pp. 5

- Sandweiss, (1992), pp. 23-24