Julian Steward

Julian Haynes Steward (January 31, 1902 – February 6, 1972) was an American anthropologist best known for his role in developing "the concept and method" of cultural ecology, as well as a scientific theory of culture change.

Julian Haynes Steward | |

|---|---|

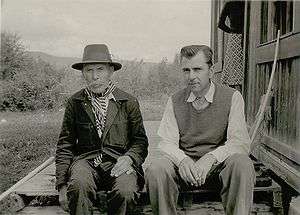

Unidentified Native Man (Carrier Indian) (possibly Steward's informant, Chief Louis Billy Prince) and Julian Steward (1902–1972) Outside Wood Building, 1940 | |

| Born | January 31, 1902 |

| Died | February 6, 1972 (aged 70) |

| Education | B.A. in Zoology, Cornell University (1925)

M.A. in Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley (1928) Ph.D. in Anthropology, University of California, Berkeley (1929) |

| Occupation | Anthropologist |

| Spouse(s) | Dorothy Nyswander (1894–1998) (married 1930–1932); Jane Cannon Steward (1908–1988) (married 1933–1972) |

| Children | Garriott Steward

Michael Steward two grandchildren |

| Anthropology |

|---|

|

|

Key theories |

|

Lists

|

Early life and education

Steward was born in Washington, D.C., where he lived on Monroe Street, NW, and later, Macomb Street in Cleveland Park.

At age 16, Steward left an unhappy childhood in Washington, D.C. to attend boarding school in Deep Springs Valley, California, in the Great Basin. Steward's experience at the newly established Deep Springs Preparatory School (which later became Deep Springs College), high in the White Mountains had a significant influence on his academic and career interests. Steward’s “direct engagement” with the land (specifically, subsistence through irrigation and ranching) and the Northern Paiute that lived there became a “catalyst” for his theory and method of cultural ecology. (Kerns 1999; Murphy 1977)

As an undergraduate, Steward studied for a year at Berkeley under Alfred Kroeber and Robert Lowie, after which he transferred to Cornell University, from which he graduated in 1925 with a B.Sc. in Zoology. Although Cornell, like most universities at the time, had no anthropology department, its president, Livingston Farrand, had previously held appointment as a professor of anthropology at Columbia University. Farrand advised Steward to continue pursuing his interest (or, in Steward's words, his already chosen "life work") in anthropology at Berkeley (Kerns 2003:71–72). Steward studied under Kroeber and Lowie—and was taught by Oskar Schmieder in regional geography—at Berkeley, where his dissertation The Ceremonial Buffoon of the American Indian, a Study of Ritualized Clowning and Role Reversals was accepted in 1929.

Career

Steward went on to establish an anthropology department at the University of Michigan, where he taught until 1930, when he was replaced by Leslie White, with whose model of "universal" cultural evolution he disagreed, although it went on to become popular and gained the department fame/notoriety. In 1930 Steward moved to the University of Utah, which appealed to him for its proximity to the Sierra Nevada, and nearby archaeological fieldwork opportunities in California, Nevada, Idaho, and Oregon.

Steward's research interests centered on "subsistence"—the dynamic interaction of man, environment, technology, social structure, and the organization of work—an approach Kroeber regarded as "eccentric", original, and innovative. (EthnoAdmin 2003) In 1931, Steward, pressed for money, began fieldwork on the Great Basin Shoshone under the auspices of Kroeber's Culture Element Distribution (CED) survey; in 1935 he received an appointment to the Smithsonian's Bureau of American Ethnography (BAE), which published some of his most influential works. Among them: Basin-Plateau Aboriginal Sociopolitical Groups (1938), which "fully explicated" the paradigm of cultural ecology, and marked a shift away from the diffusionist orientation of American anthropology.

For eleven years Steward became an administrator of considerable clout, editing the Handbook of South American Indians. He also took a position at the Smithsonian Institution, where he founded the Institute for Social Anthropology in 1943. He also served on a committee to reorganize the American Anthropological Association and played a role in the creation of the National Science Foundation. He was also active in archaeological pursuits, successfully lobbying Congress to create the Committee for the Recovery of Archaeological Remains (the beginning of what is known today as 'salvage archaeology') and worked with Gordon Willey to establish the Viru Valley project, an ambitious research program centered in Peru.

Steward searched for cross-cultural regularities in an effort to discern laws of culture and culture change. His work explained variation in the complexity of social organization as being limited to within a range possibilities by the environment. In evolutionary terms, he located this view of cultural ecology as "multi-linear", in contrast to the unilinear typological models popular in the 19th century, and Leslie White's "universal" approach. Steward's most important theoretical contributions came during his teaching years at Columbia (1946–53).

Steward's most theoretically productive years were from 1946–1953, while teaching at Columbia University. At this time, Columbia saw an influx of World War II veterans who were attending school thanks to the GI Bill. Steward quickly developed a coterie of students who would go on to have enormous influence in the history of anthropology, including Sidney Mintz, Eric Wolf, Roy Rappaport, Stanley Diamond, Robert Manners, Morton Fried, Robert F. Murphy, and influenced other scholars such as Marvin Harris. Many of these students participated in the Puerto Rico Project, yet another large-scale group research study that focused on modernization in Puerto Rico.

Steward left Columbia for the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he chaired the Anthropology Department and continued to teach until his retirement in 1968. There he undertook yet another large-scale study, a comparative analysis of modernization in eleven third world societies. The results of this research were published in three volumes entitled Contemporary Change in Traditional Societies. Steward died in 1972.

Work and influence

In addition to his role as a teacher and administrator, Steward is most remembered for his method and theory of cultural ecology. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, American anthropology was suspicious of generalizations and often unwilling to draw broader conclusions from the meticulously detailed monographs that anthropologists produced. Steward is notable for moving anthropology away from this more particularist approach and developing a more nomothetic, social-scientific direction. His theory of "multilinear" cultural evolution examined the way in which societies adapted to their environment. This approach was more nuanced than Leslie White's theory of "universal evolution", which was influenced by thinkers such as Lewis Henry Morgan. Steward's interest in the evolution of society also led him to examine processes of modernization. He was one of the first anthropologists to examine the way in which national and local levels of society were related to one another. He questioned the possibility of creating a social theory which encompassed the entire evolution of humanity; yet, he also argued that anthropologists are not limited to description of specific, existing cultures. Steward believed it is possible to create theories analyzing typical, common culture, representative of specific eras or regions. As the decisive factors determining the development of a given culture, he pointed to technology and economics, while noting that there are secondary factors, such as political systems, ideologies, and religions. These factors push the evolution of a given society in several directions at the same time.

Coming from a scientific background, Steward initially focused on ecosystems and physical environments, but soon took interest on how these environments could influence cultures (Clemmer 1999: ix). It was during Steward's teaching years at Columbia, which lasted until 1952, that he wrote arguably his most important theoretical contributions: "Cultural Causality and Law: A Trial Formulation of the Development of Early Civilizations (1949b), "Area Research: Theory and Practice" (1950), "Levels of Sociocultural Integration" (1951), "Evolution and Process (1953a), and "The Cultural Study of Contemporary Societies: Puerto Rico" (Steward and Manners 1953). Clemmer writes, "Altogether, the publications released between 1949 and 1953 represent nearly the entire gamut of Steward's broad range of interests: from cultural evolution, prehistory, and archaeology to the search for causality and cultural "laws" to area studies, the study of contemporary societies, and the relationship of local cultural systems to national ones (Clemmer 1999: xiv)." We can clearly see that Steward's diversity in subfields, extensive and comprehensive field work and a profound intellect coalesce in the form of a brilliant anthropologist.

In regard to Steward's Great Basin work, Clemmer writes, " ... [his approach] might be characterized as a perspective that people are in large part defined by what they do for a living, can be seen in his growing interest in studying the transformation of slash-and-burn horticulturists into national proletariats in South America" (Clemmer 1999: xiv). Clemmer does mention two works that contradict his characteristic style and reveal a less familiar aspect to his work, which are "Aboriginal and Historic Groups of the Ute Indians of Utah: An Analysis and Native Components of the White River Ute Indians" (1963b) and "The Northern Paiute Indians" (Steward and Wheeler-Vogelin 1954; Clemmer 1999; xiv).

References

- Clemmer, Richard O., L. Daniel Myers, and Mary Elizbeth Rudden, eds. Julian Steward and the Great Basin: the Making of an Anthropologist. University of Utah Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0874809497

- DeCamp, Elise. Julian Steward. accessed Dec. 4, 2007

- Kerns, Virginia. 2003: 151 Scenes From The High Desert: Julian Steward's Life and Theory University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252076350

- Manners, Robert A. Julian H. Steward accessed Dec. 4, 2007

- Steward, Julian H. Theory of Culture Change. University of Illinois Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0252002953