Scottish national identity

Scottish national identity is a term referring to the sense of national identity, as embodied in the shared and characteristic culture, languages and traditions,[1] of the Scottish people.

Although the various dialects of Gaelic, the Scots language and Scottish English are distinctive, people associate them all together as Scottish with a shared identity, as well as a regional or local identity. Parts of Scotland, like Glasgow, the Outer Hebrides, Orkney, Shetland, the north east of Scotland and the Scottish Borders retain a strong sense of regional identity, alongside the idea of a Scottish national identity.[2]

History

Pre-Union

Early Middle Ages

In the early Middle Ages, what is now Scotland was divided between four major ethnic groups and kingdoms. In the east were the Picts, who fell under the leadership of the kings of Fortriu.[3] In the west were the Gaelic (Goidelic)-speaking people of Dál Riata with close links with the island of Ireland, from which they brought with them the name Scots.[4] In the south-west was the British (Brythonic) Kingdom of Strathclyde, often named Alt Clut.[5] Finally there were the 'English', the Angles, a Germanic people who had established a number of kingdoms in Great Britain, including the Kingdom of Bernicia, part of which was in the south-east of modern Scotland.[6] In the late eighth century this situation was transformed by the beginning of ferocious attacks by the Vikings, who eventually settled in Galloway, Orkney, Shetland and the Hebrides. These threats may have speeded a long-term process of gaelicisation of the Pictish kingdoms, which adopted Gaelic language and customs. There was also a merger of the Gaelic and Pictish crowns. When he died as king of the combined kingdom in 900, Domnall II (Donald II) was the first man to be called rí Alban (i.e. King of Alba).[7]

High Middle Ages

In the High Middle Ages the word "Scot" was only used by Scots to describe themselves to foreigners, amongst whom it was the most common word. They called themselves Albanach or simply Gaidel. Both "Scot" and Gaidel were ethnic terms that connected them to the majority of the inhabitants of Ireland. At the beginning of the thirteenth century, the author of De Situ Albanie noted: "The name Arregathel [Argyll] means margin of the Scots or Irish, because all Scots and Irish are generally called 'Gattheli'."[8] Scotland came to possess a unity which transcended Gaelic, French and Germanic ethnic differences and by the end of the period, the Latin, French and English word "Scot" could be used for any subject of the Scottish king. Scotland's multilingual Scoto-Norman monarchs and mixed Gaelic and Scoto-Norman aristocracy all became part of the "Community of the Realm", in which ethnic differences were less divisive than in Ireland and Wales.[9] This identity was defined in opposition to English attempts to annexe the country and as a result of social and cultural changes. The resulting antipathy towards England dominated Scottish foreign policy well into the fifteenth century, making it extremely difficult for Scottish kings like James III and James IV to pursue policies of peace towards their southern neighbour.[10] In particular the Declaration of Arbroath asserted the ancient distinctiveness of Scotland in the face of English aggression, arguing that it was the role of the king to defend the independence of the community of Scotland. This document has been seen as the first "nationalist theory of sovereignty".[11]

Late Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages has often been seen as the era in which Scottish national identity was initially forged, in opposition to English attempts to annexe the country, led by figures such as Robert the Bruce and William Wallace and as a result of social and cultural changes. English invasions and interference in Scotland have been judged to have created a sense of national unity and a hatred towards England which dominated Scottish foreign policy well into the 15th century, making it extremely difficult for Scottish kings like James III and James IV to pursue policies of peace towards their southern neighbour.[10] In particular the Declaration of Arbroath (1320) asserted the ancient distinctiveness of Scotland in the face of English aggression, arguing that it was the role of the king was to defend the independence of the community of Scotland and has been seen as the first "nationalist theory of sovereignty".[11]

The adoption of Middle Scots by the aristocracy has been seen as building a sense of national solidarity and culture between rulers and ruled, although the fact that North of the Tay Gaelic still dominated, may have helped widen the cultural divide between Highlands and Lowlands.[12] The national literature of Scotland created in the late medieval period employed legend and history in the service of the crown and nationalism, helping to foster a sense of national identity at least within its elite audience. The epic poetic history of The Brus and Wallace helped outline a narrative of united struggle against the English enemy. Arthurian literature differed from conventional version of the legend by treating Arthur as a villain and Mordred, the son of the king of the Picts, as a hero.[12] The origin myth of the Scots, systematised by John of Fordun (c. 1320-c. 1384), traced their beginnings from the Greek prince Gathelus and his Egyptian wife Scota, allowing them to argue superiority over the English, who claimed their descent from the Trojans, who had been defeated by the Greeks.[11]

It was in this period that the national flag emerged as a common symbol. The image of St. Andrew martyred bound to an X-shaped cross first appeared in the Kingdom of Scotland during the reign of William I and was again depicted on seals used during the late 13th century; including on one particular example used by the Guardians of Scotland, dated 1286.[13] Use of a simplified symbol associated with Saint Andrew, the saltire, has its origins in the late 14th century; the Parliament of Scotland decreed in 1385 that Scottish soldiers wear a white Saint Andrew's Cross on their person, both in front and behind, for the purpose of identification. Use of a blue background for the Saint Andrew's Cross is said to date from at least the 15th century.[14] The earliest reference to the Saint Andrew's Cross as a flag is to be found in the Vienna Book of Hours, circa 1503.[15]

Like most western European monarchies, the Scottish crown in the fifteenth century adopted the example of the Burgundian court, through formality and elegance putting itself at the centre of culture and political life, defined with display, ritual and pageantry, reflected in elaborate new palaces and patronage of the arts.[16] Renaissance ideas began to influence views on government, described as New or Renaissance monarchy, which emphasised the status and significance of the monarch. The Roman Law principle that "a king is emperor in his own kingdom" can be seen in Scotland from the mid-fifteenth century. In 1469 Parliament passed an act that declared that James III possessed "full jurisdiction and empire within his realm".[17] From the 1480s the king's image on his silver groats showed him wearing a closed, arched, imperial crown, in place of the open circlet of medieval kings, probably the first coin image of its kind outside of Italy. It soon began to appear in heraldry, on royal seals, manuscripts, sculptures and the steeples of churches with royal connections, as at St. Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh.[17]

Sixteenth century

The idea of imperial monarchy emphasised the dignity of the crown and included its role as a unifying national force, defending national borders and interest, royal supremacy over the law and a distinctive national church within the Catholic communion. James V was the first Scottish monarch to wear the closed imperial crown, in place of the open circlet of medieval kings, suggesting a claim to absolute authority within the kingdom.[17] His diadem was reworked to include arches in 1532, which were re-added when it was reconstructed in 1540 in what remains the Crown of Scotland.[17] During her brief personal rule Mary, Queen of Scots brought many of the elaborate court activities that she had grown up with at the French court, with balls, masques and celebrations, designed to illustrate the resurgence of the monarchy and to facilitate national unity.[18] However, her personal reign ended in civil war, deposition, imprisonment and execution in England. Her infant son James VI was crowned King of Scots in 1567.[19]

By the early modern era Gaelic had been in geographical decline for three centuries and had begun to be a second class language, confined to the Highlands and Islands. It was gradually being replaced by Middle Scots, which became the language of both the nobility and the majority population. Scots was derived substantially from Old English, with Gaelic and French influences. It was called Inglyshe in the fifteenth century and was very close to the language spoken in northern England,[20] but by the sixteenth century it had established orthographic and literary norms largely independent of those developing in England.[21] From the mid-sixteenth century, written Scots was increasingly influenced by the developing Standard English of Southern England due to developments in royal and political interactions with England.[22] With the increasing influence and availability of books printed in England, most writing in Scotland came to be done in the English fashion.[23] Unlike many of his predecessors, James VI generally despised Gaelic culture.[24]

After the Reformation there was the development of a national kirk that claimed to represent all of Scotland. It became the subject of national pride, and was often compared with the less clearly reformed church in neighbouring England. Jane Dawson suggests that the loss of national standing in the contest for dominance of Britain between England and France suffered by the Scots, may have led them to stress their religious achievements.[25] A theology developed that saw the kingdom as in a covenant relationship with God. Many Scots saw their country as a new Israel and themselves as a holy people engaged in a struggle between the forces of Christ and Antichrist, the later being identified with the resurgent papacy and the Roman Catholic Church. This view was reinforced by events elsewhere that demonstrated that Reformed religion was under threat, such as the 1572 Massacre of St Bartholomew in France and the Spanish Armada in 1588.[25] These views were popularised through the first Protestant histories, such as Knox's History of the Reformation and George Buchanan's Rerum Scoticarum Historia.[26] This period also saw a growth of a patriotic literature facilitated by the rise of popular printing. Published editions of medieval poetry by John Barbour and Robert Henryson and the plays of David Lyndsay all gained a new audience.[27]

Seventeenth century

In 1603, James VI King of Scots inherited the throne of the Kingdom of England and left Edinburgh for London where he would reign as James I.[28] The Union was a personal or dynastic union, with the crowns remaining both distinct and separate—despite James' best efforts to create a new "imperial" throne of "Great Britain".[29] James used his Royal prerogative powers to take the style of "King of Great Britain"[30] and to give an explicitly British character to his court and person, and attempted to create a political union between England and Scotland.[31] The two parliaments established a commission to negotiate a union, formulating an instrument of union between the two countries. However, the idea of political union was unpopular, and when James dropped his policy of a speedy union, the topic quietly disappeared from the legislative agenda. When the House of Commons attempted to revive the proposal in 1610, it was met with a more open hostility.[32]

The Protestant identification of Scotland as a "new Israel", emphasising a covenant with God,[33] emerged at the front of national politics in 1637, as Presbyterians rebelled against Charles I's liturgical reforms and signed the National Covenant.[34] In the subsequent Wars of Three Kingdoms Scottish armies marched under the saltire of St. Andrew, rather than the lion rampant, with slogans such as "Religion, Crown, Covenant and Country".[35] After defeats at Dunbar (1650) and Worcester (1651) Scotland was occupied and in 1652 declared part of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland. Although it had supporters, the independence of Scotland as a kingdom was restored with the Stuart monarchy in 1660.[36]

In the Glorious Revolution in 1688–89, the Catholic James VII was replaced by the Protestant William of Orange, Stadtholder of the Netherlands and his wife Mary, James's daughter, on the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland.[36] The final settlement restored Presbyterianism and abolished the bishops, who had generally supported James. The result left the nation divided between a predominately Presbyterian Lowland and a predominately Episcopalian Highland region.[37] Support for James, which became known as Jacobitism, from the Latin (Jacobus) for James, led to a series of risings, beginning with John Graham of Claverhouse, Viscount Dundee. His forces, almost all Highlanders, defeated William's forces at the Battle of Killiecrankie in 1689, but they took heavy losses and Dundee was slain in the fighting. Without his leadership the Jacobite army was soon defeated at the Battle of Dunkeld.[38] During the following years, William proposed a complete union to the Parliament of Scotland in 1700 and 1702, but the proposals were rejected.[39]

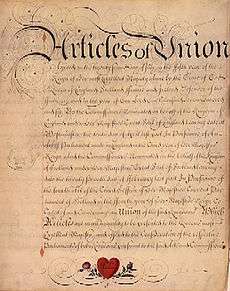

Union

William's successor was Mary's sister Anne, who had no surviving children and so the Protestant succession seemed in doubt. The English Parliament passed the Act of Settlement 1701, which fixed the succession on Sophia of Hanover and her descendants. However, the Scottish Parliament's parallel Act of Security, merely prohibited a Roman Catholic successor, leaving open the possibility that the crowns would diverge. Rather than risk the possible return of James Francis Edward Stuart, then living in France, the English parliament pressed for full union of the two countries, passing the Alien Act 1705, which threatened to make all Scotsmen unable to hold property in England unless moves toward union were made and would have severely damaged the cattle and linen trades. A political union between Scotland and England was also seen as economically attractive, promising to open up the much larger markets of England, as well as those of the growing Empire.[40] However, there was widespread, if disunited opposition and mistrust in the general population.[41] Sums paid to Scottish commissioners and leading political figure have been described as bribes, but the existence of direct bribes is disputed.[42] The Treaty of Union confirmed the Hanoverian succession. The Church of Scotland and Scottish law and courts remained separate, while Scotland retained its distinctive system of parish schools. The English and Scottish parliaments were replaced by a combined Parliament of Great Britain, but it sat in Westminster and largely continued English traditions without interruption. Forty-five Scots were added to the 513 members of the House of Commons and 16 Scots to the 190 members of the House of Lords.[42] Rosalind Mitchison argues that the parliament became a focus of national political life, but it never attained the position of a true centre of national identity attained by its English counterpart.[43] It was also a full economic union, replacing the Scottish systems of currency, taxation and laws regulating trade.[42] The Privy Council was abolished, which meant that effective government in Scotland lay in the hands of unofficial "managers".[44]

Early Union (1707–1832)

Jacobitism

Jacobitism was revived by the unpopularity of the union with England in 1707.[41] In 1708 James Francis Edward Stuart, the son of James VII, who became known as "The Old Pretender", attempted an invasion with French support.[45] The two most serious risings were in 1715 and 1745. The first was soon after the death of Anne and the accession of the first Hanoverian king George I. It envisaged simultaneous uprisings in England, Wales and Scotland, but they only developed in Scotland and Northern England. John Erskine, Earl of Mar, raised the Jacobite clans in the Highlands. Mar was defeated at Battle of Sheriffmuir and day later part of his forces, who had joined up with risings in northern England and southern Scotland, were defeated at the Battle of Preston. By the time the Old Pretender arrived in Scotland the rising was all but defeated and he returned to continental exile.[46] The 1745 rising was led by Charles Edward Stuart, son of the Old Pretender, often referred to as Bonnie Prince Charlie or the Young Pretender.[47] His support was almost exclusively among the Highland clans. The rising enjoyed initial success, with Highland armies defeating Hanoverian forces and occupying Edinburgh before an abortive march that reached Derby in England.[48] Charles' position in Scotland began to deteriorate as the Scottish Whig supporters rallied and regained control of Edinburgh. He retreated north to be defeated at Culloden on 16 April 1746.[49] There were bloody reprisals against his supporters and foreign powers abandoned the Jacobite cause, with the court in exile forced to leave France. The Old Pretender died in 1760 and the Young Pretender, without legitimate issue, in 1788. When his brother, Henry, Cardinal of York, died in 1807, the Jacobite cause was at an end.[50] The Jacobite risings highlighted the social and cultural schism within Scotland, between the "improved," English and Scots-speaking Lowlands and the underdeveloped Gaelic-speaking Highlands.[51]

Language

After the Union in 1707 and the shift of political power to England, the use of Scots was discouraged by many in authority and education, as was the notion of Scottishness itself.[52] Many leading Scots of the period, such as David Hume, considered themselves Northern British rather than Scottish.[53] They attempted to rid themselves of their Scots in a bid to establish standard English as the official language of the newly formed Union.[23] Many well-off Scots took to learning English through the activities of those such as Thomas Sheridan, who in 1761 gave a series of lectures on English elocution. Charging a guinea at a time (about £200 in today's money[54]) they were attended by over 300 men, and he was made a freeman of the City of Edinburgh. Following this, some of the city's intellectuals formed the Select Society for Promoting the Reading and Speaking of the English Language in Scotland.[55] Nevertheless, Scots remained the vernacular of many rural lowland communities and the growing number of urban working-class Scots.[56] In the Highlands, Gaelic language and culture persisted, and the region as a whole was seen as an "other" by lowlanders.

Literature and Romanticism

Although Scotland increasingly adopted the English language and wider cultural norms, its literature developed a distinct national identity and began to enjoy an international reputation. Allan Ramsay (1686–1758) laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, as well as leading the trend for pastoral poetry, helping to develop the Habbie stanza as a poetic form.[57] James Macpherson was the first Scottish poet to gain an international reputation, claiming to have found poetry written by ancient bard Ossian, he published translations that acquired international popularity, being proclaimed as a Celtic equivalent of the Classical epics. Fingal written in 1762 was speedily translated into many European languages, and its deep appreciation of natural beauty and the melancholy tenderness of its treatment of the ancient legend did more than any single work to bring about the Romantic movement in European, and especially in German, literature, influencing Herder and Goethe.[58] Eventually it became clear that the poems were not direct translations from the Gaelic, but flowery adaptations made to suit the aesthetic expectations of his audience.[59]

Robert Burns and Walter Scott were highly influenced by the Ossian cycle. Burns, an Ayrshire poet and lyricist, is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and a major figure in the Romantic movement. As well as making original compositions, Burns also collected folk songs from across Scotland, often revising or adapting them. His poem (and song) "Auld Lang Syne" is often sung at Hogmanay (the last day of the year), and "Scots Wha Hae" served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem of the country.[60] Scott began as a poet and also collected and published Scottish ballads. His first prose work, Waverley in 1814, is often called the first historical novel.[61] It launched a highly successful career that probably more than any other helped define and popularise Scottish cultural identity.[62]

Tartanry

In the 1820s, as part of the Romantic revival, tartan and the kilt were adopted by members of the social elite, not just in Scotland, but across Europe.[63][64] Walter Scott's "staging" of the royal Visit of King George IV to Scotland in 1822 and the king's wearing of tartan resulted in a massive upsurge in demand for kilts and tartans that could not be met by the Scottish linen industry. The designation of individual clan tartans was largely defined in this period and they became a major symbol of Scottish identity.[65] The fashion for all things Scottish was maintained by Queen Victoria who help secure the identity of Scotland as a tourist resort and the popularity of the tartan fashion.[64] This "tartanry" identified Scottish identity with the previously despised or distrusted Highland identity and may have been a response to the disappearance of traditional Highland society, increasing industrialisation and urbanisation.[66]

The romanticisation of the Highlands and the adoption of Jacobitism into mainstream culture have been seen as defusing the potential threat to the Union with England, the House of Hanover and the dominant Whig government.[67] In many countries Romanticism played a major part in the emergence of radical independence movements through the development of national identities. Tom Nairn argues that Romanticism in Scotland did not develop along the lines seen elsewhere in Europe, leaving a "rootless" intelligentsia, who moved to England or elsewhere and so did not supply a cultural nationalism that could be communicated to the emerging working classes.[68] Graeme Moreton and Lindsay Paterson both argue that the lack of interference of the British state in civil society meant that the middle classes had no reason to object to the union.[68] Atsuko Ichijo argues that national identity cannot be equated with a movement for independence.[69] Moreton suggests that there was a Scottish nationalism, but that it was expressed in terms of "Unionist nationalism".[70]

Victorian and Edwardian eras (1832–1910)

Industrialisation

From the second half of the eighteenth century Scotland was transformed by the process of Industrial Revolution, emerging as one of the commercial and industrial centres of the British Empire.[71] It began with trade with Colonial America, first in tobacco and then rum, sugar and cotton.[72][73] The cotton industry declined due to blockades during the American Civil War, but by this time Scotland had developed as a centre for coal mining, engineering, shipbuilding and the production of locomotives, with steel production largely replacing iron production in the late nineteenth century.[74] This resulted in rapid urbanisation in the industrial belt that ran across the country from southwest to northeast; by 1900 the four industrialised counties of Lanarkshire, Renfrewshire, Dunbartonshire, and Ayrshire contained 44 per cent of the population.[75] These industrial developments, while they brought work and wealth, were so rapid that housing, town-planning, and provision for public health did not keep pace with them, and for a time living conditions in some of the towns and cities were notoriously bad, with overcrowding, high infant mortality, and growing rates of tuberculosis.[76] The new companies attracted rural workers, as well as large numbers immigrants from Catholic Ireland, changing the religious balance and national character, particularly in the urban centres of the west.[77] In cities like Glasgow a sense of civic pride emerged as it expanded to become the "second city of the Empire", while the corporation remodelled the town and controlled transport, communications and housing.[78]

Michael Lynch sees a new British state emerging in the wake of the Reform Act of 1832.[79] This began the widening of the electoral franchise, from less than 5,000 landholders, which was to continue with further acts in 1868 and 1884.[80] Lynch argues that there were concentric identities for Scots, where "a new Scottishness, a new Britishness and a revised sense of local pride – were held together by a phenomenon bigger than all of them – a Greater Britain whose stability rested on the Empire".[78] Lynch also argues that the three main institutions which protected Scotland's identity - the Church, education and the law - were all on the retreat in this period.[81]

Religious fragmentation

The late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw a fragmentation of the Church of Scotland that had been created in the Reformation. These fractures were prompted by issues of government and patronage, but reflected a wider division between the Evangelicals and the Moderate Party over fears of fanaticism by the former and the acceptance of Enlightenment ideas by the latter. The legal right of lay patrons to present clergymen of their choice to local ecclesiastical livings led to minor schisms from the church. The first in 1733, known as the First Secession, led to the creation of a series of secessionist churches. The second in 1761 lead to the foundation of the independent Relief Church.[82] Gaining strength in the Evangelical Revival of the later eighteenth century[83] and after prolonged years of struggle, in 1834 the Evangelicals gained control of the General Assembly and passed the Veto Act, which allowed congregations to reject unwanted "intrusive" presentations to livings by patrons. The following "Ten Years' Conflict" of legal and political wrangling ended in defeat for the non-intrusionists in the civil courts. The result was a schism from the church by some of the non-intrusionists led by Dr Thomas Chalmers known as the Great Disruption of 1843. Roughly a third of the clergy, mainly from the North and Highlands, formed the separate Free Church of Scotland. In the late nineteenth century the major debates were between fundamentalist Calvinists and theological liberals, who rejected a literal interpretation of the Bible. This resulted in a further split in the Free Church as the rigid Calvinists broke away to form the Free Presbyterian Church in 1893.[82] Until the Disruption the Church of Scotland had been seen as the religious expression of national identity and the guardian of Scotland's morals. It had considerable control over moral discipline, schools and the poor law system, but after 1843 it was a minority church, with reduced moral authority and control of the poor and education.[84]

In the late nineteenth century the established church began to recover, embarking on a programme of church building to rival the Free Church, increasing its number of parishes from 924 in 1843 to 1,437 by 1909.[85] There were also moves towards reunion, beginning with the unification of some secessionist churches into the United Secession Church in 1820, which united with the Relief Church in 1847 to form the United Presbyterian Church, which in turn joined with the Free Church in 1900. The removal of legislation on lay patronage allowed the majority of the Free Church to rejoin Church of Scotland in 1929. The schisms left small denominations including the Free Presbyterians and a remnant as the Free Church from 1900.[82]

Education

The Industrial Revolution and rapid urbanisation undermined the effectiveness of the Scottish church school system that had grown up since the Reformation, creating major gaps in provision and religious divisions would begin to undermine the unity of the system.[86] The publication of George Lewis's Scotland: a Half Educated Nation in 1834 began a major debate on the suitability of the parish school system, particularly in rapidly expanding urban areas.[81] Aware of the growing shortfall in provision the Kirk set up an education committee in 1824. The committee had established 214 "assembly schools" between 1824 and 1865 and 120 "sessional schools", were mainly established by kirk sessions in towns and aimed at the children of the poor.[87] The Disruption of 1843 fragmented the kirk school system, with 408 teachers in schools joining the breakaway Free Church. By May 1847 it was claimed that 500 schools had been built by the new church, along with two teacher training colleges and a ministerial training college.[88] The influx of large numbers of Irish immigrants in the nineteenth century led to the establishment of Catholic schools, particularly in the urban west of the country, beginning with Glasgow in 1817.[89] The church schools system was now divided between three major bodies, the established Kirk, the Free Church and the Catholic Church.[87] The perceived problems and fragmentation of the Scottish school system led to a process of secularisation, as the state took increasing control. From 1830 the state began to fund buildings with grants, then from 1846 it was funding schools by direct sponsorship.[90] The 1861 Education Act removed the provision stating that Scottish teachers had to be members of the Church of Scotland or subscribe to the Westminster Confession. Under the 1872 Education (Scotland) Act, approximately 1,000 regional School Boards were established[91] which took over the schools of the old and new kirks.[92] and the boards undertook a major programme that created large numbers of grand, purpose-built schools.[92] Overall administration was in the hands of the Scotch (later Scottish) Education Department in London.[90]

Law

The union with England meant that Scottish law was perceived as being increasingly Anglicised. Particularly in the first third of the nineteenth century, there a number of reforms to the judicial system and legal procedure that brought it increasingly in to line with English practice, such as trial by jury in civil cases, which was introduced in 1814. As Home Secretary in the 1820s, Robert Peel justified changes on the grounds that the Scottish system was "totally different from English practice and rather repugnant to English feelings".[93] New areas of public policy that had not been part of Scottish law, in areas such as public health, working conditions, the protection of investors, were legislated for by the British Parliament, challenging the uniqueness of the Scottish system.[81] In the late nineteenth century, commercial law saw increasing assimilation as Scottish law was replaced by increasingly English-based measures such as the Partnership Act 1890 and the Sale of Goods Act 1893. Lord Rosebery summed up the fears of Anglicisation in 1882, stating that the new legislation was framed on the principle that "every part of the United Kingdom must be English, because it is part of the United Kingdom".[93]

Early nationalist movements

Unlike many parts of continental Europe there was no major insurrection in Scotland in the 1840s and early moves toward nationalism tended to be aimed at improvement of the union, rather than its abolition. The first political organisation with such a nationalist agenda was the National Association for the Vindication of Scottish Rights, formed in 1853. It highlighted grievances, drew comparisons with the more generous treatment of Ireland and argued that there should be more Scottish MPs at Westminster. Having attracted few figures of significance the association was wound up in 1856,[94] but it provided an agenda drawn upon by subsequent national movements.[79] Resentment over the preferential deal discussed for Ireland during the Irish Home Rule debates in the later nineteenth century revived interest in constitutional reform and helped create a politically significant Scottish Home Rule movement. However, this was not a movement that aimed at independence. It argued for the devolution of Scottish business to Edinburgh to make Westminster more efficient and it was taken for granted that the union was vital to the progress and improvement of Scotland. Meanwhile, Scottish Highland crofters took inspiration from the Irish Land League set up to campaign for land reform in Ireland and defend the interests of Irish tenant farmers. Highlanders in turn founded the Highland Land League. The efforts for land reform in the Highlands expanded into a parliamentary arm of the movement, the Crofters Party. In the event, unlike the highly successful Irish Parliamentary Party, the new political party proved short-lived and was soon co-opted by the Liberal Party, but not before helping secure key concessions from the Liberals, which resulted in the rights of crofters becoming enshrined in law. Not all Scots saw common cause with Irish nationalism - the widely popular Scottish Unionist Association that emerged in 1912 from a merger of the Scottish Conservatives and Liberal Unionists referred to the Irish Union of 1801, while the union between Scotland and England was taken for granted and largely unthreatened.[94]

World Wars (1914–1960)

In the years leading up to the first World War, Scotland found herself on the verge of devolution. The Liberals were in power at Whitehall, largely confirmed by the Scots, and they were about to legislate on Irish Home Rule. Gaelic culture was on the rise, and long lasting disputes within the Church had finally been settled.

Economic conditions, 1914–1922

Between 1906 and 1908, output of the Clyde shipbuilding industry declined by 50 percent.[95] At the time, the steel and engineering industries were also depressed. These were ominous signs for an economy based on eight staple industries (agriculture, coal mining, shipbuilding, engineering, textiles, building, steel, and fishing) which accounted for 60 percent of Scotland's industrial output. With 12.5 percent of the UK production output and 10.5 percent of its population, Scotland's economy was a significant part of the overall British picture. Despite economic hardship, Scotland participated in World War I. Initially enthusiastic about the war, with Scotland mobilising 22 out of the 157 battalions which made up the British Expeditionary Force, concern about the wartime threat to an exporting economy soon came to the forefront. Fear that the war would lead to disastrous conditions for industrial areas, with increased unemployment, abated as the German offensive on the Western Front came to a halt. In the Glasgow Herald, MP William Raeburn said:

The War has falsified almost every prophecy. Food was to be an enormous price [sic] unemployment rife ... Revolution was to be feared. What are the facts? The freight market ... is now active and prosperous ... Prices of food have risen very little, and the difficulty at present is to get sufficient labour, skilled and unskilled. We have not only maintained our own trades, but have been busy capturing our enemies'.

However, the textile industry was immediately impacted by 30– to 40-percent increases in freight and insurance costs. Coal mining was also affected, since the German and Baltic markets disappeared during the war; the German market had consisted of 2.9 million tons. Enlistment resulted in a decline of efficiency, since the remaining miners were less skilled, older or in poor physical condition. The fishing industry was affected because the main importers of herring were Germany and Russia, and the war resulted in the enlistment of a large number of fishermen in the Royal Naval Reserve.

Industries benefiting from the war were shipbuilding and munitions. Although they had a positive effect on employment, their production had a limited future; when the war ended in 1918, so did the orders which had kept the Clyde shipyards busy. The war scarred the Scottish economy for years to come.

World War I had exacted an enormous sacrifice from the Scots; the National War Memorial White Paper estimated a loss of about 100,000 men. At five percent of the male population, this was nearly double the British average. Capital from the expanded munitions industry moved south with the control of much Scottish business. English banks took over Scottish banks, and the remaining Scottish banks switched much of their investment to government stocks or English businesses. According to the Glasgow Herald (usually no friend of nationalism), "Ere long the commercial community will be sighing for a banking William Wallace to free them from southern oppression".

The war brought a new desolation to the Scottish Highlands. Forests were cut, and death and migration ended traditional industries. Schemes were made to restore the area: reforestation, railway construction and industrialisation of the islands along a Scandinavian pattern emphasising deep-sea fishing. However, implementing the plans depended on continuing British economic prosperity.

A reorganisation of the railways was critically important. The newly created Ministry of Transport suggested nationalising the railways with a separate, autonomous Scottish region. The scheme would greatly strain the Scottish railways, as had been seen under wartime national control (leading to upgraded maintenance and wages and a rise in expenses). A Scottish company would be forced to uphold the standards, although it would be carrying just over half the freight of the English railway. A campaign, headed by a coalition of Scottish MPs from the Labour, Liberal and Conservative parties, used the rhetoric of nationalism to secure the amalgamation of Scottish and English railways.

This was an example of how nationalism could be tied to economics; any economic disadvantage relative to the rest of the UK could be used by politicians to justify intervention by a devolved or independent administration.[96] Scotland had been near a vote on devolution before the outbreak of World War I; although economic problems were not new, they were not a case for nationalism before 1914. Governmental intervention was social in nature from 1832 to 1914, when the major issues were social welfare and the educational system. Actions affecting the economy were not considered functions of government before 1914.

The Scottish electorate increased from 779,012 in 1910 to 2,205,383 in 1918 due to the Representation of the People Act 1918, which entitled women over 30 to vote and increased the number of male voters by 50 percent.[97] Although Labour had home rule on its program, supporting it with two planks (self-determination for the Scottish people and the restoration of Scotland to the Scottish people), the Unionists received 32 seats in the Commons—up from seven in 1910. The period following World War I was one of unprecedented depression because of the war's impact on the economy.

Economic conditions from 1922–1960

The Scottish economy was heavily dependent on international trade. A decline in the trade would mean over capacity in shipping and a fall in owner's profit. This again would lead to fewer orders for new ships, and this slump would then spread to the other heavy industries. In 1921 the shipbuilding industry had been hit by the combination of a vanishing naval market, the surplus of products of U.S. shipyards, and confiscated enemy ships.

Scotland needed to plan its way out of trouble. In 1930 the Labour government had, though it was considered a purely cosmetic move, encouraged regional industrial development groups, which led to the forming of the Scottish National Development Council (SNDC). The forming of the SNDC later led to the set up of the Scottish Economy Committee (SEC). Neither of these bodies sought a cure for Scotland's ills by nationalist political solutions, and many of those who were actively involved in them joined in a comprehensive condemnation of any form of home rule.[98] However, at the same time the secretary of the committee justified its existence by stating: "It is undoubtedly true that Scotland's national economy tends to pass unnoticed in the hands of the Ministry of Labour and the Board of Trade". Because increasing legislation required more Scottish statutes, the importance of the legal and the administrative in the years between the wars grew. The move of the administration to St. Andrew's House was considered an important act, but while welcoming the move in 1937, Walter Elliot – the Secretary of State then – feared the changes:

"[...] will not in themselves dispose of the problems whose solution a general improvement in Scottish social and economic conditions depends [...] it is the consciousness of their existence which is reflected in, not in the small and unimportant Nationalist Party, but in the dissatisfaction and uneasiness amongst moderate and reasonable people of every view or rank – a dissatisfaction expressed in every book published about Scotland now for several years".

As government began to play an increasingly interventionist role in the economy, it became easy to advocate a nationalist remedy to ensure that it was in what ever was deemed Scotland's interest. As before 1914, the easy conditions of world trade after 1945 made Scottish industry prosper, and any need for drastic political interventions were postponed until the late 1950s, when the economic progress of Scotland started to deteriorate, and shipbuilding and engineering companies were forced to shut down. But even if the decline in the late 1950s meant an increasing degree of intervention from the government, there was no evidence of any other political change. Even the Scottish Council's inquiry into the Scottish economy in 1960 was specific: "The proposal for a Scottish Parliament [...] implies constitutional changes of a kind that place it beyond our remit although it is fair to say that we do not regard it as a solution".

Literary renaissance

While the post 1914 period appears to have been devoted to the economic questions and problems of Scotland, it also saw the birth of a Scottish literary renaissance in the 1924–1934 decade.

In the late 18th and 19th century, industrialisation had swept across Scotland with great speed. Such was the rate of industrialisation that the Scottish society had failed to adequately adapt to the massive changes which industrialisation had brought. The Scottish intelligentsia was overwhelmed by the growth of the Scottish industrial revolution, and the new entrepreneurial bourgeoisie linked to it. It was "deprived of its typical nationalist role. [...] There was no call for its usual services".[99] These 'services' would normally lead the nation to the threshold of political independence. So the, indeed, very well known intelligentsia of Scotland was operating on an entirely different stage, though it was not really Scottish at all. As a contrast, or perhaps a reaction to this, an entirely different literary "school" erupted in the late 19th century: the Kailyard.

Along with Tartanry, Kailyard has come to represent a "cultural sub-nationalism". The Kailyard literature, and the garish symbols of Tartanry, fortified each other and became a sort of substitute for nationalism. The parochialism of the Kailyard, and the myths of an irreversible past of the Tartanry, came to represent a politically impotent nationalism.

One of the first to recognise this "lack of teeth" was the poet Hugh MacDiarmid. MacDiarmid, both a nationalist and a socialist, saw the parochialism of the Scottish literature as a sign of English hegemony, hence it had to be destroyed. He tried to do this through his poetry, and used his own reworking of old Scots or "Lallans" (Lowland Scots) in the tradition of Robert Burns instead of Scots Gaelic or standard English.[100] MacDiarmid's "crusade" brought along other writers and poets, like Lewis Grassic Gibbon and Edwin Muir; but this literary renaissance lasted only for about ten years.

1960–present day

Research conducted by the Scottish Social Attitudes Survey in 1979 found that more than 95% of those living in Scotland identified as "Scottish" in varying degrees, with more than 80% identifying themselves as "British" in varying degrees.[101] When forced to choose a single national identity between "Scottish" and "British", 57% identified as Scottish and 39% identified as British.[101] British national identity entered a sharp decline in Scotland from 1979 until the advent of devolution in 1999. In 2000, when forced to choose a single national identity between "Scottish" and "British", 80% identified as Scottish and only 13% identified as British, however 60% still identified as British to some degree.[102][103]

Polling conducted since 2014 has indicated that when forced to choose between "Scottish" and "British" identities, British national identity has risen to between 31-36% in Scotland and Scottish national identity has fallen to between 58-62%.[104] Other national identities such as "European" and "English" have remained fairly static in Scotland since 1999 at between 1-2%.[102]

Among the most commonly cited reasons for the rise in Scottish national identity and coinciding decline in British national identity in Scotland between 1979-1999 is the Premiership of Margaret Thatcher and the consecutive Premiership of John Major from 1979-1997: Conservative Prime Ministers who finished second behind the Labour Party in Scotland though won the ballot across the UK as a whole and implemented unpopular policies such as the ill-fated poll tax in Scotland.[105][106] The establishment of a devolved Scottish Parliament in 1999 and the holding of a referendum on Scottish independence in 2014 have been recognised as factors contributing to a gradual rise in British national identity in Scotland and a decline in Scottish national identity since 1999.[101][104]

Devolution

Scottish National Party and Scottish independence

The Scottish National Party (or SNP) is a political party in Scotland which seeks to remove Scotland from the United Kingdom in favour of forming an independent Scottish state. The party sat on the fringes of politics in Scotland after losing the Motherwell parliamentary constituency at the 1945 general election, until the party won a by-election in the Labour stronghold of Hamilton in 1967. In the subsequent 1970 general election, the party gained its first seat in a UK Parliamentary election in the Western Isles.

In 1970, large quantities of oil were discovered off the coast of Scotland. The SNP exploited this with their highly successful "It's Scotland's Oil" campaign: arguing that during the 1973–75 recession that the oil would belong within the territorial boundaries of an independent Scotland and would help to mitigate the effects of the economic recession in Scotland should Scotland become independent.[107][108] The party won 7 seats and 21.9% of the vote in the February 1974 general election and won 11 seats and 30.4% of the vote in the October 1974 general election, before losing the vast majority of their seats to Labour and the Conservatives in 1979.

A referendum was held on Scottish devolution in 1979, which would result in the establishment of a devolved autonomous Scottish Assembly, however the referendum failed to pass as despite a narrow lead for the devolution side, with 52% in favour of devolution, a low turnout of 32.9% of the entire Scottish electorate failed to meet the required 40% turnout threshold set out by the UK Parliament for the election outcome to be valid.[109]

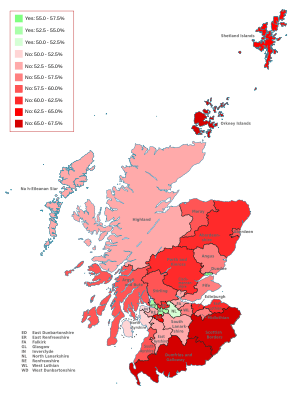

The establishment of a devolved Scottish Parliament in 1999 has since provided the SNP with a platform to win elections in Scotland, forming a minority government from 2007 until 2011, and a majority government from 2011 until 2016, during which time the Parliament approved the holding of a referendum on Scottish independence from the UK which was held with the consent of the United Kingdom government. The referendum was held on 18 September 2014, with 55.3% voting against independence and 44.7% voting in favour on a high turnout of 84.6%.

The vast majority of those identifying their national identity more as "British" support Scotland remaining a part of the United Kingdom, with a smaller majority of those identifying their national identity more as "Scottish" supporting Scottish independence.[110] However, many independence supporters also identify as "British" in varying degrees, with a majority of those describing their national identity as "More Scottish than British" being supportive of Scottish independence.[110]

The SNP returned to office as a minority government in 2016. The First Minister of Scotland Nicola Sturgeon said in the immediate aftermath of the 2016 UK EU membership referendum that second referendum on Scottish independence was "highly likely" after Scotland voted to remain within the EU on a margin of 62% remain 38% leave, despite a UK-wide result of 52% leave,[111] however she subsequently put the plans on hold after facing a setback at the 2017 general election where the SNP lost 21 out of its 56 seats from 2015 and saw its vote share fall from 50.0% to 36.9%.[112]. However, in the 2019 general election, the SNP won 48 of Scotland's 59 seats [113], with the SNP's manifesto stating "It’s a vote for Scotland’s right to choose our own future in a new independence referendum."[114]

Cultural icons

Cultural icons in Scotland have changed over the centuries, e.g., the first national instrument was the clàrsach or Celtic harp until it was replaced by the Great Highland bagpipe in the 15th century.[115] Symbols like tartan, the kilt and bagpipes are widely but not universally liked by Scots; their establishment as symbols for the whole of Scotland, especially in the Lowlands, dates back to the early 19th century. This was the age of pseudo-pageantry: the visit of King George IV to Scotland organised by Sir Walter Scott. Scott, very much a Unionist and Tory, was at the same time a great populariser of Scottish mythology through his writings.

See also

- A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle

- A Man's A Man for A' That

- Jock Tamsons Bairns

- Scottish people

- Scottish cringe

- List of Scotland-related topics

References

- "National identity | Definition of national identity in US English by Oxford Dictionaries".

- Lynch, Michael (2001). The Oxford Companion to Scottish history. Oxford University Press. pp. 504–509. ISBN 978-0-19-211696-3.

- A. P. Smyth, Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0-7486-0100-7, pp. 43–6.

- A. Woolf, From Pictland to Alba: 789 – 1070 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0-7486-1234-3, pp. 57–67.

- A. Macquarrie, "The kings of Strathclyde, c. 400–1018", in G. W. S. Barrow, A. Grant and K. J. Stringer, eds, Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998), ISBN 0-7486-1110-X, p. 8.

- J. R. Maddicott and D. M. Palliser, eds, The Medieval State: essays presented to James Campbell (London: Continuum, 2000), ISBN 1-85285-195-3, p. 48.

- A. O. Anderson, Early Sources of Scottish History, A.D. 500 to 1286 (General Books LLC, 2010), vol. i, ISBN 1-152-21572-8, p. 395.

- A. O. Anderson, Early Sources of Scottish History: AD 500–1286, 2 Vols, (Edinburgh, 1922). vol. i. p. cxviii.

- G. W. S. Barrow, Kingship and Unity: Scotland 1000–1306 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0-7486-0104-X, pp. 122–43.

- A. D. M. Barrell, Medieval Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), ISBN 0-521-58602-X, p. 134.

- C. Kidd, Subverting Scotland's Past: Scottish Whig Historians and the Creation of an Anglo-British Identity 1689–1830 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), ISBN 0-521-52019-3, pp. 17–18.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-7486-0276-3, pp. 66–7.

- "Feature: Saint Andrew seals Scotland's independence". The National Archives of Scotland. 28 November 2007. Archived from the original on 16 September 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

- Bartram, Graham (2004). British Flags & Emblems. Tuckwell Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-86232-297-4.

The blue background dates back to at least the 15th century.

www.flaginstitute.org Archived 9 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine - Bartram, Graham (2001), "The Story of Scotland's Flags" (PDF), Proceedings of the XIX International Congress of Vexillology, York, United Kingdom: Fédération internationale des associations vexillologiques, pp. 167–172, retrieved 9 December 2009

- Wormald (1991), p. 18.

- A. Thomas, "The Renaissance", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0191624330, p. 188.

- A. Thomas, "The Renaissance", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), ISBN 0191624330, pp. 192–3.

- P. Croft, King James (Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), ISBN 0-333-61395-3, p. 11.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 60–1.

- J. Corbett, D. McClure and J. Stuart-Smith, "A Brief History of Scots" in J. Corbett, D. McClure and J. Stuart-Smith, eds, The Edinburgh Companion to Scots (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1596-2, p. 9ff.

- J. Corbett, D. McClure and J. Stuart-Smith, "A Brief History of Scots" in J. Corbett, D. McClure and J. Stuart-Smith, eds, The Edinburgh Companion to Scots (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1596-2, p. 10ff.

- J. Corbett, D. McClure and J. Stuart-Smith, "A Brief History of Scots" in J. Corbett, D. McClure and J. Stuart-Smith, eds, The Edinburgh Companion to Scots (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1596-2, p. 11.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, p. 40.

- J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0-7486-1455-9, pp. 232–3.

- C. Erskine, "John Knox, George Buccanan and Scots prose" in A. Hadfield, ed., The Oxford Handbook of English Prose 1500–1640 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), ISBN 0199580685, p. 636.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0-7126-9893-0, p. 184.

- D. Ross, Chronology of Scottish History (Geddes & Grosset, 2002), ISBN 1-85534-380-0, p. 56.

- D. L. Smith, A History of the Modern British Isles, 1603–1707: The Double Crown (Wiley-Blackwell, 1998), ISBN 0631194029, ch. 2.

- Larkin; Hughes, eds. (1973). Stuart Royal Proclamations: Volume I. Clarendon Press. p. 19.

- Lockyer, R. (1998). James VI and I. London: Addison Wesley Longman. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-0-582-27962-9.

- R. Lockyer, James VI and I, (London: Longman, 1998), ISBN 0-582-27962-3, p. 59.

- J. E. A. Dawson, Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), ISBN 0748614559, p. 340.

- J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, p. 22.

- M. Lynch, "National Identify: 3 1500–1700" in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 439–41.

- J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 241–5.

- J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 252–3.

- J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 283–4.

- M. Lynch, Scotland: A New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0712698930, pp. 307–09.

- J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, p. 202.

- M. Pittock, Jacobitism (St. Martin's Press, 1998), ISBN 0312213069, p. 32.

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805, p. 314.

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805, p. 128.

- J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 282–4.

- M. Pittock, Jacobitism (St. Martin's Press, 1998), ISBN 0-312-21306-9, p. 33.

- R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-415-27880-5, pp. 269–74.

- M. McLaren, Bonnie Prince Charlie (New York, NY: Dorset Press, 1972), pp. 39–40.

- M. McLaren, Bonnie Prince Charlie (New York, NY: Dorset Press, 1972), pp. 69–75.

- M. McLaren, Bonnie Prince Charlie (New York, NY: Dorset Press, 1972), pp. 145–150.

- J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0-14-013649-5, p. 298.

- I. Duncan, "Walter Scott, James Hogg and Scottish Gothic", in D. Punter, ed., A New Companion to The Gothic (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2015), ISBN 1119062500, p. 124.

- C. Jones, A Language Suppressed: The Pronunciation of the Scots Language in the 18th Century (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1993), p. vii.

- C. Jones, A Language Suppressed: The Pronunciation of the Scots Language in the 18th Century (Edinburgh: John Donald, 1993), p. 2.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- J. Corbett, D. McClure and J. Stuart-Smith, "A Brief History of Scots" in J. Corbett, D. McClure and J. Stuart-Smith, eds, The Edinburgh Companion to Scots (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1596-2, p. 13.

- J. Corbett, D. McClure and J. Stuart-Smith, "A Brief History of Scots" in J. Corbett, D. McClure and J. Stuart-Smith, eds, The Edinburgh Companion to Scots (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1596-2, p. 14.

- J. Buchan (2003), Crowded with Genius, Harper Collins, p. 311, ISBN 978-0060558888.

- J. Buchan (2003), Crowded with Genius, Harper Collins, p. 163, ISBN 978-0060558888.

- D. Thomson (1952), The Gaelic Sources of Macpherson's "Ossian", Aberdeen: Oliver & Boyd.

- L. McIlvanney (Spring 2005), "Hugh Blair, Robert Burns, and the Invention of Scottish Literature", Eighteenth-Century Life, 29 (2): 25–46, doi:10.1215/00982601-29-2-25.

- K. S. Whetter (2008), Understanding Genre and Medieval Romance, Ashgate, p. 28, ISBN 978-0754661429.

- N. Davidson (2000), The Origins of Scottish Nationhood, Pluto Press, p. 136, ISBN 978-0745316086.

- J. L. Roberts, The Jacobite Wars: Scotland and the Military Campaigns of 1715 and 1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2002), ISBN 1-902930-29-0, pp. 193–5.

- M. Sievers, The Highland Myth as an Invented Tradition of 18th and 19th Century and Its Significance for the Image of Scotland (GRIN Verlag, 2007), ISBN 3638816516, pp. 22–5.

- N. C. Milne, Scottish Culture and Traditions (Paragon Publishing, 2010), ISBN 1-899820-79-5, p. 138.

- I. Brown, From Tartan to Tartanry: Scottish Culture, History and Myth (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010), ISBN 0748638776, pp. 104–105.

- F. McLynn, The Jacobites (London: Taylor & Francis, 1988), ISBN 0415002672, p. 211.

- A. Ichijo, Scottish Nationalism and the Idea of Europe: Concepts Of Europe and the Nation (London: Routledge, 2004), ISBN 0714655910, pp. 35–6.

- A. Ichijo, Scottish Nationalism and the Idea of Europe: Concepts Of Europe and the Nation (London: Routledge, 2004), ISBN 0714655910, p. 37.

- A. Ichijo, Scottish Nationalism and the Idea of Europe: Concepts Of Europe and the Nation (London: Routledge, 2004), ISBN 0714655910, pp. 3–4.

- T. A. Lee, Seekers of Truth: the Scottish Founders of Modern Public Accountancy (Bingley: Emerald Group, 2006), ISBN 0-7623-1298-X, pp. 23–4.

- Robert, Joseph C. (1976), "The Tobacco Lords: A study of the Tobacco Merchants of Glasgow and their Activities", The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 84 (1): 100–102, JSTOR 4248011.

- R. H. Campbell, "The Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707. II: The Economic Consequences," Economic History Review, April 1964 vol. 16, pp. 468–477 in JSTOR.

- C. A. Whatley, The Industrial Revolution in Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), ISBN 0-521-57643-1, p. 51.

- I. H. Adams, The Making of Urban Scotland (Croom Helm, 1978).

- C. H. Lee, Scotland and the United Kingdom: the Economy and the Union in the Twentieth Century (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), ISBN 0-7190-4101-5, p. 43.

- J. Melling, "Employers, industrial housing and the evolution of company welfare policies in Britain's heavy industry: west Scotland, 1870–1920", International Review of Social History, Dec 1981, vol. 26 (3), pp. 255–301.

- M. Lynch, Scotland a New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0-7126-9893-0, p. 359.

- M. Lynch, Scotland a New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0-7126-9893-0, p. 358.

- O. Checkland and S. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd ed., 1989), ISBN 0748601023, p. 66.

- M. Lynch, Scotland a New History (London: Pimlico, 1992), ISBN 0-7126-9893-0, p. 357.

- J. T. Koch, Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1–5 (London: ABC-CLIO, 2006), ISBN 1-85109-440-7, pp. 416–17.

- G. M. Ditchfield, The Evangelical Revival (Abingdon: Routledge, 1998), ISBN 1-85728-481-X, p. 91.

- S. J. Brown, "The Disruption" in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 170-2.

- C. Brooks, "Introduction", in C. Brooks, ed., The Victorian Church: Architecture and Society (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), ISBN 0-7190-4020-5, pp. 17–18.

- T. M. Devine, The Scottish Nation, 1700–2000 (London: Penguin Books, 2001), ISBN 0-14-100234-4, pp. 91–100.

- O. Checkland and S. G. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland, 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0748601023, p. 111.

- G. Parsons, "Church and state in Victorian Scotland: disruption and reunion", in G. Parsons and J. R. Moore, eds, Religion in Victorian Britain: Controversies (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988), ISBN 0719025133, p. 116.

- J. C. Conroy, "Catholic Education in Scotland", in M. A. Hayes and L. Gearon, eds, Contemporary Catholic Education (Gracewing, 2002), ISBN 0852445288, p. 23.

- "Education records", National Archive of Scotland, 2006, archived from the original on 2 July 2011

- L. Patterson, "Schools and schooling: 3. Mass education 1872–present", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 566–9.

- O. Checkland and S. G. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland, 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989), ISBN 0748601023, pp. 112–13.

- I. G. C., Hutchison, "Political relations in the nineteenth century", in T. Christopher Smout, ed, Anglo-Scottish Relations from 1603 to 1900 (London: OUP/British Academy, 2005), ISBN 0197263305, p. 256.

- T. M. Devine, "In bed with an elephant: almost three hundred years of the Anglo-Scottish Union", Scottish Affairs, 57, Autumn 2006, p. 2.

- Harvie, Christopher: "No Gods and Precious Few Heroes", Edinburgh University Press, 1993 – p. 1

- Campbell, R. H.: "The Economic Case for Nationalism" from Rosalind Mitchinson: The Roots of Nationalism: Studies in Northern Europe, John Donald Publishers, 1980 – p. 143

- Lynch, Michael: Scotland – A New History, Pimlico, 1992 – p. 428

- Campbell, R. H.: "The Economic Case for Nationalism" from Rosalind Mitchinson: The Roots of Nationalism: Studies in Northern Europe, John Donald Publishers, 1980 – p. 150

- Nairn, Tom: The Break Up of Britain, Low and Brydone Printers, 1977 – p. 154

- Thomsen, Robert Christian: Tartanry, Aalborg Universitet, 1995 – p. 77

- "British Social Attitudes Survey" (PDF). Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- "What Scotland Thinks". Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- "What Scotland Thinks". Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- "What Scotland Thinks". Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- "Scotland's independence leader on how Margaret Thatcher helped Scottish nationalism". Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- Tilley, James; Heath, Anthony (2007). "The decline of British national pride". The British Journal of Sociology. 58 (4): 661–678. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00170.x. PMID 18076390.

- Lynch, Michael: "Scotland – A New History", Pimlico, 1992 – p. 446

- Pugh, Martin: "State and Society – British Political and Social History 1870–1992", Arnold, 1994 – p. 293

- Osmond, John: "The Divided Kingdom", Constable, 1988 – p. 71

- "Scottish Social Attitudes: From Indeyref1 to Indeyref2?, page 8" (PDF). 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- "Scotland must have choice over future". Scottish Government. 13 March 2017. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- "Nicola Sturgeon puts Scottish independence referendum bill on hold". BBC. 27 June 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- "General Election 2019: full results and analysis". House of Commons Library. 28 January 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- "SNP Manifesto - General Election 2019". Scottish National Party. 26 November 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Farmer, Henry George (1947): A History of Music in Scotland London, 1947 p. 202.

Further reading

- Abstract of Constructing National Identity: Arts and Landed Elites in Scotland, by Frank Bechhofer, David McCrone, Richard Kiely and Robert Stewart, Research Centre for Social Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Cambridge University Press, 1999

- Abstract of The markers and rules of Scottish national identity, by Richard Kiely, Frank Bechhofer, Robert Stewart and David McCrone, The Sociological Review, Volume 49 Page 33 – February 2001,

- National Identities in Post-Devolution Scotland, by Ross Bond and Michael Rosie, Institute of Governance, University of Edinburgh, June 2002

- Abstract of Near and far: banal national identity and the press in Scotland, by Alex Law, University of Abertay Dundee, Media, Culture and Society, Vol. 23, No. 3, 299–317 (2001)

- Abstract of Scottish national identities among inter-war migrants in North America and Australasia, by Angela McCarthy, The Journal of Imperial & Commonwealth History, Volume 34, Number 2 / June 2006

- Scottish Newspapers and Scottish National Identity in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, by IGC Hutchison, University of Stirling, 68th IFLA Council and General Conference, 18–24 August 2002

- Condor, Susan and Jackie Abell (2007) Vernacular constructions of 'national identity' in post-devolution Scotland and England (pp. 51–76) in J. Wilson & K. Stapleton (Eds) Devolution and Identity Aldershot: Ashgate.

- PDF file from essex.ac.uk: Welfare Solidarity in a Devolved Scotland, by Nicola McEwen, Politics, School of Social and Political Studies, University of Edinburgh, European Consortium for Political Research Joint Sessions, 28 March – 2 April 2003