Scotland in the modern era

Scotland in the modern era, from the end of the Jacobite risings and beginnings of industrialisation in the 18th century to the present day, has played a major part in the economic, military and political history of the United Kingdom, British Empire and Europe, while recurring issues over the status of Scotland, its status and identity have dominated political debate.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Scotland |

|

|

|

|

By Region |

|

|

Scotland made a major contribution to the intellectual life of Europe, particularly in the Enlightenment, producing major figures including the economist Adam Smith, philosophers Francis Hutcheson and David Hume, and scientists William Cullen, Joseph Black and James Hutton. In the 19th century major figures included James Watt, James Clerk Maxwell, Lord Kelvin and Sir Walter Scott. Scotland's economic contribution to the Empire and the industrial revolution included its banking system and the development of cotton, coal mining, shipbuilding and an extensive railway network. Industrialisation and changes to agriculture and society led to depopulation and clearances of the largely rural highlands, migration to the towns and mass emigration, where Scots made a major contribution to the development of countries including the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

In the 20th century, Scotland played a major role in the British and allied effort in the two world wars and began to suffer a sharp industrial decline, going through periods of considerable political instability. The decline was particularly acute in the second half of the 20th century, but was compensated for to a degree by the development of an extensive oil industry, technological manufacturing and a growing service sector. This period also increasing debates about the place of Scotland within the United Kingdom, the rise of the Scottish National Party and after a referendum in 1999 the establishment of a devolved Scottish Parliament.

Late 18th century and 19th century

With the advent of the Union with England and the demise of Jacobitism, thousands of Scots, mainly Lowlanders, took up positions of power in politics, civil service, the army and navy, trade, economics, colonial enterprises and other areas across the nascent British Empire. Historian Neil Davidson notes that "after 1746 there was an entirely new level of participation by Scots in political life, particularly outside Scotland". Davidson also states that "far from being 'peripheral' to the British economy, Scotland – or more precisely, the Lowlands – lay at its core".[1]

Politics

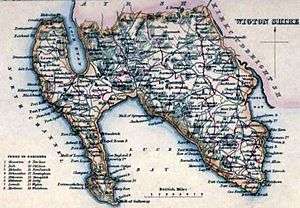

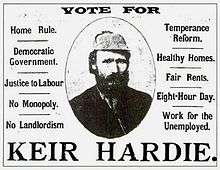

Scottish politics in the late 18th century and throughout the 19th century was dominated by the Whigs and (after 1859) their successors the Liberal Party. From the Scottish Reform Act 1832 (which increased the number of Scottish MPs and significantly widened the franchise to include more of the middle classes), until the end of the century they managed to gain a majority of the Westminster Parliamentary seats for Scotland, although these were often outnumbered by the much larger number of English and Welsh Conservatives.[2] English-educated Scottish peer Lord Aberdeen (1784–1860) led a coalition government from 1852 to 1855, but in general very few Scots held office in the government.[3] From the mid-century there were increasing calls for Home Rule for Scotland and when the Conservative Lord Salisbury became prime minister in 1885 he responded to pressure for more attention to be paid to Scottish issues by reviving the post of Secretary of State for Scotland, which had been in abeyance since 1746.[4] He appointed the Duke of Richmond, a wealthy landowner who was both Chancellor of Aberdeen University and Lord Lieutenant of Banff.[5] Towards the end of the century the first Scottish Liberal to become prime minister was the Earl of Rosebery (1847–1929), like Aberdeen before him a product of the English education system.[6] In the later 19th century the issue of Irish Home Rule led to a split among the Liberals, with a minority breaking away to form the Liberal Unionists in 1886.[2] The growing importance of the working classes was marked by Keir Hardie's success in the Mid Lanarkshire by-election, 1888, leading to the foundation of the Scottish Labour Party, which was absorbed into the Independent Labour Party in 1895, with Hardie as its first leader.[7]

The main unit of local government was the parish, and since it was also part of the church, the elders imposed public humiliation for what the locals considered immoral behaviour, including fornication, drunkenness, wife beating, cursing and Sabbath breaking. The main focus was on the poor and the landlords ("lairds") and gentry, and their servants, were not subject to the parish's discipline. The policing system weakened after 1800 and disappeared in most places by the 1850s.[8]

Enlightenment

In the 18th century, the Scottish Enlightenment brought the country to the front of intellectual achievement in Europe. Perhaps the poorest country in Western Europe in 1707, Scotland reaped the economic benefits of free trade within the British Empire together with the intellectual benefits of a highly developed university system.[9] Under these twin stimuli, Scottish thinkers began questioning assumptions previously taken for granted; and with Scotland's traditional connections to France, then in the throes of the Enlightenment, the Scots began developing a uniquely practical branch of humanism to the extent that Voltaire said "we look to Scotland for all our ideas of civilization".[10]

The first major philosopher of the Scottish Enlightenment was Francis Hutcheson, who held the Chair of Philosophy at the University of Glasgow from 1729 to 1746. A moral philosopher who produced alternatives to the ideas of Thomas Hobbes, one of his major contributions to world thought was the utilitarian and consequentialist principle that virtue is that which provides, in his words, "the greatest happiness for the greatest numbers". Much of what is incorporated in the scientific method (the nature of knowledge, evidence, experience, and causation) and some modern attitudes towards the relationship between science and religion were developed by his proteges David Hume and Adam Smith.[11]

Hume became a major figure in the sceptical philosophical and empiricist traditions of philosophy. He and other Scottish Enlightenment thinkers developed what he called a 'science of man',[12] which was expressed historically in works by authors including James Burnett, Adam Ferguson, John Millar and William Robertson, all of whom merged a scientific study of how humans behave in ancient and primitive cultures with a strong awareness of the determining forces of modernity. Indeed, modern sociology largely originated from this movement.[13] Adam Smith developed and published The Wealth of Nations, the first work on modern economics. It had an immediate impact on British economic policy and still frames 21st century discussions on globalisation and tariffs.[14] The focus of the Scottish Enlightenment ranged from intellectual and economic matters to the specifically scientific as in the work of William Cullen, physician and chemist, James Anderson, an agronomist, Joseph Black, physicist and chemist, and James Hutton, the first modern geologist.[11][15] While the Scottish Enlightenment is traditionally considered to have concluded toward the end of the 18th century,[12] disproportionately large Scottish contributions to British science and letters continued for another 50 years or more, thanks to such figures as James Hutton, James Watt, William Murdoch, James Clerk Maxwell, Lord Kelvin and Sir Walter Scott.[16]

Religion

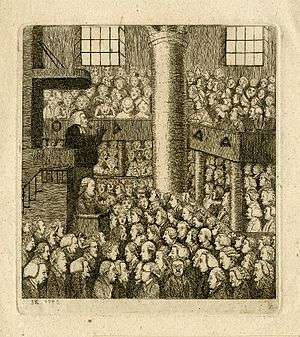

The late 18th and 19th centuries saw a fragmentation of the Church of Scotland that had been created in the Reformation. These fractures were prompted by issues of government and patronage, but reflected a wider division between the Evangelicals and the Moderate Party over fears of fanaticism by the former and the acceptance of Enlightenment ideas by the latter. The legal right of lay patrons to present clergymen of their choice to local ecclesiastical livings led to minor schisms from the church. The first in 1733, known as the First Secession, led to the creation of a series of secessionist churches. The second in 1761 lead to the foundation of the independent Relief Church.[17] Gaining strength in the Evangelical Revival of the later 18th century[18] and after prolonged years of struggle, in 1834 the Evangelicals gained control of the General Assembly and passed the Veto Act, which allowed congregations to reject unwanted "intrusive" presentations to livings by patrons. The following "Ten Years' Conflict" of legal and political wrangling ended in defeat for the non-intrusionists in the civil courts. The result was a schism from the church by some of the non-intrusionists led by Dr Thomas Chalmers known as the Great Disruption of 1843. Roughly a third of the clergy, mainly from the North and Highlands, formed the separate Free Church of Scotland. In the late 19th century the major debates were between fundamentalist Calvinists and theological liberals, who rejected a literal interpretation of the Bible. This resulted in a further split in the Free Church as the rigid Calvinists broke away to form the Free Presbyterian Church in 1893.[17] There were, however, also moves towards reunion, beginning with the unification of some secessionist churches into the United Secession Church in 1820, which united with the Relief Church in 1847 to form the United Presbyterian Church, which in turn joined with the Free Church in 1900. The removal of legislation on lay patronage allowed the majority of the Free Church to rejoin Church of Scotland in 1929. The schisms left small denominations including the Free Presbyterians and a remnant as the Free Church from 1900.[17]

By the mid-18th century, Catholicism had been reduced to the fringes of the country, particularly the Gaelic-speaking areas of the Highlands and Islands. Conditions grew worse for Catholics after the Jacobite risings and Catholicism was reduced to little more than a poorly run mission. However, Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and the influx of large numbers of Irish immigrants, particularly after the famine years of the late 1840s, principally to the growing lowland centres like Glasgow, led to a transformation of its fortunes. In 1878, despite opposition, a Roman Catholic ecclesiastical hierarchy was restored to the country, and Catholicism became a significant denomination within Scotland.[17] Also important was Episcopalianism, which had retained supporters through the civil wars and changes of regime in the 17th century. Since most Episcopalians had given their support to the Jacobite risings in the early 18th century they suffered a decline in fortunes, but revived in the 19th as the issue of succession receded, becoming established as the Episcopal Church in Scotland in 1804, as an autonomous organisation in communion with the Church of England.[17] Baptist, Congregationalist and Methodist churches also appeared in Scotland in the 18th century, but did not begin significant growth until the 19th century,[17] partly because more radical and evangelical traditions already existed within the Church of Scotland and the free churches. From 1879 they were joined by the evangelical revivalism of the Salvation Army, which attempted to make major inroads in the growing urban centres.[18]

Industrial Revolution

During the Industrial Revolution, Scotland became one of the commercial and industrial centres of the British Empire.[19] With tariffs with England now abolished, the potential for trade for Scottish merchants was considerable, especially with Colonial America. However, the economic benefits of union were very slow to appear, primarily because Scotland was too poor to exploit the opportunities of the greatly expanded free market. Scotland in 1750 was still a poor rural, agricultural society with a population of 1.3 million.[20] Some progress was visible, such as the sales of linen and cattle to England, the cash flows from military service, and the tobacco trade that was dominated by Glasgow after 1740. The clippers belonging to the Glasgow Tobacco Lords were the fastest ships on the route to Virginia.[21] Merchants who profited from the American trade began investing in leather, textiles, iron, coal, sugar, rope, sailcloth, glassworks, breweries, and soapworks, setting the foundations for the city's emergence as a leading industrial centre after 1815.[22] The tobacco trade collapsed during the American Revolution (1776–83), when it sources were cut off by the British blockade of American ports. However, trade with the West Indies began to make up for the loss of the tobacco business,[23] reflecting the extensive growth of the cotton industry, the British demand for sugar and the demand in the West Indies for herring and linen goods. During 1750–1815, 78 Glasgow merchants not only specialised in the importation of sugar, cotton, and rum from the West Indies, but diversified their interests by purchasing West Indian plantations, Scottish estates, or cotton mills. They were not to be self-perpetuating due to the hazards of the trade, the incident of bankruptcy, and the changing complexity of Glasgow's economy.[24]

Linen was Scotland's premier industry in the 18th century and formed the basis for the later cotton, jute,[25] and woollen industries.[26] Scottish industrial policy was made by the Board of Trustees for Fisheries and Manufactures in Scotland, which sought to build an economy complementary, not competitive, with England. Since England had woollens, this meant linen. Encouraged and subsidised by the Board of Trustees so it could compete with German products, merchant entrepreneurs became dominant in all stages of linen manufacturing and built up the market share of Scottish linens, especially in the American colonial market.[27] The British Linen Company, established in 1746, was the largest firm in the Scottish linen industry in the 18th century, exporting linen to England and America. As a joint-stock company, it had the right to raise funds through the issue of promissory notes or bonds. With its bonds functioning as bank notes, the company gradually moved into the business of lending and discounting to other linen manufacturers, and in the early 1770s banking became its main activity. Renamed the British Linen Bank in 1906, it was one of Scotland's premier banks until it was bought out by the Bank of Scotland in 1969.[28] It joined the established Scottish banks such as the Bank of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1695) and the Royal Bank of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1727).[29] Glasgow would soon follow and Scotland had a flourishing financial system by the end of the century. There were over 400 branches, amounting to one office per 7000 people, double the level in England. The banks were more lightly regulated than those in England. Historians often emphasise that the flexibility and dynamism of the Scottish banking system contributed significantly to the rapid development of the economy in the 19th century.[30][31]

From about 1790 textiles became the most important industry in the west of Scotland, especially the spinning and weaving of cotton, which flourished until in 1861 the American Civil War cut off the supplies of raw cotton.[32] The industry never recovered, but by that time Scotland had developed heavy industries based on its coal and iron resources. The invention of the hot blast for smelting iron (1828) revolutionised the Scottish iron industry. As a result, Scotland became a centre for engineering, shipbuilding and the production of locomotives. Toward the end of the 19th century, steel production largely replaced iron production.[33]

Coal mining became a major industry, and continued to grow into the 20th century, producing the fuel to heat homes, factories and drive steam engines, locomotives and steamships. By 1914 there were 1,000,000 coal miners in Scotland. The stereotype emerged early on of Scottish colliers as brutish, non-religious and socially isolated serfs;[34] that was an exaggeration, for their life style resembled coal miners everywhere, with a strong emphasis on masculinity, egalitarianism, group solidarity, and support for radical labour movements.[35]

Britain was the world leader in the construction of railways, and their use to expand trade and coal supplies. The first successful locomotive-powered line in Scotland, between Monkland and Kirkintilloch, opened in 1831.[36] Not only was good passenger service established by the late 1840s, but an excellent network of freight lines reduce the cost of shipping coal, and made products manufactured in Scotland competitive throughout Britain. For example, railways opened the London market to Scottish beef and milk. They enabled the Aberdeen Angus to become a cattle breed of worldwide reputation.[37][38]

Urbanisation

.jpg)

Scotland was already one of the most urbanised societies in Europe by 1800.[39] The industrial belt ran across the country from southwest to northeast; by 1900 the four industrialised counties of Lanarkshire, Renfrewshire, Dunbartonshire, and Ayrshire contained 44 per cent of the population.[40] Glasgow and the River Clyde became a major shipbuilding centre. Glasgow became one of the largest cities in the world, and known as "the Second City of the Empire" after London.[41] Shipbuilding on Clydeside (the river Clyde through Glasgow and other points) began when the first small yards were opened in 1712 at the Scott family's shipyard at Greenock. After 1860 the Clydeside shipyards specialised in steamships made of iron (after 1870, made of steel), which rapidly replaced the wooden sailing vessels of both the merchant fleets and the battle fleets of the world. It became the world's pre-eminent shipbuilding centre. Clydebuilt became an industry benchmark of quality, and the river's shipyards were given contracts for warships, as well as prestigious liners. It reached its peak in the years 1900–18, with an output of 370 ships completed in 1913, and even more during the First World War.[42]

The industrial developments, while they brought work and wealth, were so rapid that housing, town-planning, and provision for public health did not keep pace with them, and for a time living conditions in some of the towns and cities were notoriously bad, with overcrowding, high infant mortality, and growing rates of tuberculosis.[43] The companies attracted rural workers, as well as immigrants from Catholic Ireland, by inexpensive company housing that was a dramatic move upward from the inner-city slums. This paternalistic policy led many owners to support government sponsored housing programs as well as self-help projects among the respectable working class.[44]

Highlands

Modern historians suggest that due to economic and social change, the clan system in the highlands was already declining by the time of the failed 1745 rising.[45] In its aftermath the British government enacted a series of laws that attempted to speed the process, including a ban on the bearing of arms, the wearing of tartan and limitations on the activities of the Episcopalian Church. Most of the legislation was repealed by the end of the 18th century as the Jacobite threat subsided. There was soon a process of the rehabilitation of highland culture. Tartan had already been adopted for highland regiments in the British army, which poor highlanders joined in large numbers until the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, but by the 19th century it had largely been abandoned by the ordinary people. In the 1820s, as part of the Romantic revival, tartan and the kilt were adopted by members of the social elite, not just in Scotland, but across Europe.[46][47] The international craze for tartan and for idealising a romanticised highlands was set off by the Ossian cycle published by Scottish poet James Macpherson's in 1761–2.[48][49] Sir Walter Scott's Waverley novels further helped popularise Scottish life and history. His "staging" of the royal Visit of King George IV to Scotland in 1822 and the king's wearing of tartan resulted in a massive upsurge in demand for kilts and tartans that could not be met by the Scottish linen industry. The designation of individual clan tartans was largely defined in this period and they became a major symbol of Scottish identity.[50] The fashion for all things Scottish was maintained by Queen Victoria who help secure the identity of Scotland as a tourist resort and the popularity of the tartan fashion. Her Highland enthusiasm led to the design of two tartan patterns, "Victoria" and "Balmoral", the latter named after her castle Balmoral in Aberdeenshire, which from 1852 became a major royal residence.[47]

The reality of the Highlands was that of an agriculturally marginal region, with only an estimated 9% of its land suitable for arable production.[51](p18) It was subject to recurrent famine and, from the 18th century onwards, was experiencing population growth.[52]:415–416 The sale of black cattle out of the region balanced an inward trade of oatmeal that was essential to sustain the peasant population.[52]:48-49 Highland landlords, who, through their integration into Scottish landowning society, were now exposed to the costs of living in London or Edinburgh and were becoming chronically indebted.[53](p417) Rents were increased. Factors and land surveyors who had studied the economic principles of the Scottish Enlightenment put forward plans for agricultural improvement to landowners who were looking to maximise the income from their lands. The usual result was the eviction of tenants who had farmed run rig arable plots and raised livestock on common grazing. Typically they were offered crofts and expected to work in other industries such as fishing or kelping.[lower-alpha 1][52]:79 Some chose to emigrate, rejecting the loss of status from farmer to crofter.[54]:173[55]:208 In the southeastern Highlands there was migration to the growing cities of the Lowlands. These evictions were the first phase of the Highland clearances.

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, the few successful industries of the Highlands went into decline: cattle prices fell and the kelp industry virtually disappeared over a few years.[56]:370–371[57]:187-191

Crofting communities had become common in the Islands and the Western Highlands. Population growth had continued, causing overcrowding: crofts were subdivided, giving less land per person on which to grow food. Their occupiers were dependent on the highly productive potato for survival. When potato blight arrived in Scotland in 1846, a famine of much greater seriousness than earlier events resulted. The blight lasted for about 10 years. Landowners were now without rents from their destitute tenants and were expected by the government to provide famine relief to them. Fortunately many Highland estates now had new owners after hereditary landlords had been compelled to sell due to their debts. These had the funds to support their tenants in the short term, and most did so. Estates that had introduced sheep farming tenants also had the income to assist their crofters. Given the length of the famine, and with suggestions that the government might introduce an "able-bodied" Poor Law, so formalising the cost of famine relief for landowners, a long-term solution was needed. It was cheaper for a landlord to pay the fare for a tenant to emigrate than have an open-ended commitment to provide food. Almost 11,000 people were provided with "assisted passages" by their landlords between 1846 and 1856, with the greatest number travelling in 1851. A further 5,000 emigrated to Australia, through the Highland and Island Emigration Society. To this should be added an unknown, but significant number, who paid their own fares to emigrate, and a further unknown number assisted by the Colonial Land and Emigration commission.[58]:201,207,268[51]:320[57]:187–189

The unequal concentration of land ownership remained an emotional subject and eventually became a cornerstone of liberal radicalism. The politically powerless poor crofters embraced the popularly oriented, fervently evangelical Presbyterian revival after 1800[59] and the breakaway "Free Church" after 1843. This evangelical movement was led by lay preachers who themselves came from the lower strata, and whose preaching was implicitly critical of the established order. The religious change energised the crofters and separated them from the landlords; it helped prepare them for their successful and violent challenge to the landlords in the 1880s through the Highland Land League.[60] Violence began on the Isle of Skye when Highland landlords cleared their lands for sheep and deer parks. It was quieted when the government stepped in passing the Crofters' Holdings (Scotland) Act, 1886 to reduce rents, guarantee fixity of tenure, and break up large estates to provide crofts for the homeless.[61] In 1885 three Independent Crofter candidates were elected to Parliament, which listened to their pleas. The results included explicit security for the Scottish smallholders; the legal right to bequeath tenancies to descendants; and creating a Crofting Commission. The Crofters as a political movement faded away by 1892, and the Liberal Party gained most of their votes.[62]

Emigration

The population of Scotland grew steadily in the 19th century, from 1,608,000 in the census of 1801 to 2,889,000 in 1851 and 4,472,000 in 1901.[63] Even with the growth of industry there were insufficient good jobs, as a result, during the period 1841–1931, about 2 million Scots emigrated to North America and Australia, and another 750,000 Scots relocated to England. By the 21st century, there were about as many people who were Scottish Canadians and Scottish Americans as the 5 million remaining in Scotland.[64] Scots born migrants played a leading role in the foundation and principles of the United States (John Witherspoon, John Paul Jones, Andrew Carnegie),[65] Canada (John A MacDonald, James Murray, Tommy Douglas),[66] Australia (Lachlan Macquarie, Thomas Brisbane, Andrew Fisher)[67] and New Zealand (James Mckenzie, Peter Fraser).[68]

Education

A legacy of the Reformation in Scotland was the aim of having a school in every parish, which was underlined by an act of the Scottish parliament in 1696 (reinforced in 1801). In rural communities these obliged local landowners (heritors) to provide a schoolhouse and pay a schoolmaster, while ministers and local presbyteries oversaw the quality of the education. In many Scottish towns, burgh schools were operated by local councils.[69] One of the effects of this extensive network of schools was the growth of the "democratic myth" in the 19th century, which created the widespread belief that many a "lad of pairts" had been able to rise up through the system to take high office and that literacy was much more widespread in Scotland than in neighbouring states, particularly England.[70] Historians now accept that very few boys were able to pursue this route to social advancement and that literacy was not noticeably higher than comparable nations, as the education in the parish schools was basic, short and attendance was not compulsory.[71]

Industrialisation, urbanisation and the Disruption of 1843 all undermined the tradition of parish schools. From 1830 the state began to fund buildings with grants, then from 1846 it was funding schools by direct sponsorship, and in 1872 Scotland moved to a system like that in England of state-sponsored largely free schools, run by local school boards.[71] Overall administration was in the hands of the Scotch (later Scottish) Education Department in London.[72] Education was now compulsory from five to thirteen and many new board schools were built. Larger urban school boards established "higher grade" (secondary) schools as a cheaper alternative to the burgh schools. The Scottish Education Department introduced a Leaving Certificate Examination in 1888 to set national standards for secondary education and in 1890 school fees were abolished, creating a state-funded national system of free basic education and common examinations.[70]

The five Scottish universities had been oriented to clerical and legal training, after the religious and political upheavals of the 17th century they recovered with a lecture-based curriculum that was able to embrace economics and science, offering a high quality liberal education to the sons of the nobility and gentry. It helped the universities to become major centres of medical education and to put Scotland at the forefront of Enlightenment thinking.[70] In the mid 19th century, the historic University of Glasgow became a leader in British higher education by providing the educational needs of youth from the urban and commercial classes, as well as the upper class. It prepared students for non-commercial careers in government, the law, medicine, education, and the ministry and a smaller group for careers in science and engineering.[73] Scottish universities would admit women from 1892.[70]

Literature

Although Scotland increasingly adopted the English language and wider cultural norms, its literature developed a distinct national identity and began to enjoy an international reputation. Allan Ramsay (1686–1758) laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, as well as leading the trend for pastoral poetry, helping to develop the Habbie stanza as a poetic form.[74] James Macpherson was the first Scottish poet to gain an international reputation, claiming to have found poetry written by Ossian, he published translations that acquired international popularity, being proclaimed as a Celtic equivalent of the Classical epics. Fingal written in 1762 was speedily translated into many European languages, and its deep appreciation of natural beauty and the melancholy tenderness of its treatment of the ancient legend did more than any single work to bring about the Romantic movement in European, and especially in German, literature, influencing Herder and Goethe.[75] Eventually it became clear that the poems were not direct translations from the Gaelic, but flowery adaptations made to suit the aesthetic expectations of his audience.[76]

Robert Burns and Walter Scott were highly influenced by the Ossian cycle. Burns, an Ayrshire poet and lyricist, is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and a major figure in the Romantic movement. As well as making original compositions, Burns also collected folk songs from across Scotland, often revising or adapting them. His poem (and song) "Auld Lang Syne" is often sung at Hogmanay (the last day of the year), and "Scots Wha Hae" served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem of the country.[77] Scott began as a poet and also collected and published Scottish ballads. His first prose work, Waverley in 1814, is often called the first historical novel.[78] It launched a highly successful career that probably more than any other helped define and popularise Scottish cultural identity.[79]

In the late 19th century, a number of Scottish-born authors achieved international reputations. Robert Louis Stevenson's work included the urban Gothic novella Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), and played a major part in developing the historical adventure in books like Kidnapped and Treasure Island. Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes stories helped found the tradition of detective fiction. The "kailyard tradition" at the end of the century, brought elements of fantasy and folklore back into fashion as can be seen in the work of figures like J. M. Barrie, most famous for his creation of Peter Pan and George MacDonald whose works including Phantasies played a major part in the creation of the fantasy genre.[80]

Art and architecture

Scotland in this era produced some of the most significant British artists and architects. The influence of Italy was particularly significant, with over fifty Scottish artists and architects known to have travelled there in the period 1730–80.[81] Many painters of the early part of the eighteenth century remained largely artisans, like the members of the Norie family, James (1684–1757) and his sons, who painted the houses of the peerage with Scottish landscapes that were pastiches of Italian and Dutch landscapes.[82] The painters Allan Ramsay (1713–84),[83] Gavin Hamilton (1723–98),[84] the brothers John (1744–1768/9) and Alexander Runciman (1736–85),[85] Jacob More (1740–93)[82] and David Allan (1744–96),[86] mostly began in the tradition of the Nories, but were artists of European significance, spending considerable portions of their careers outside Scotland, and were to varying degree influenced by forms of Neoclassicism.

The shift in attitudes to a romantic view of the Highlands at the end of the 18th century had a major impact on Scottish art.[87] Romantic depictions can be seen in the work of 18th-century artists including Jacob More,[87] and Alexander Runciman.[88] and the next generation of artists, including the portraits of Henry Raeburn (1756–1823),[89] and the landscapes of Alexander Nasmyth (1758–1840)[90] and John Knox (1778–1845).[91] The Royal Scottish Academy of Art was created in 1826, allowing professional painters to more easily exhibit and sell their works.[92] Andrew Geddes (1783–1844) and David Wilkie (1785–1841) were among the most successful portrait painters. The tradition of highland landscape painting was continued by figures such as Horatio McCulloch (1806–67), Joseph Farquharson (1846–1935) and William McTaggart (1835–1910).[93] Aberdeen born William Dyce (1806–64), emerged as one of the most significant figures in art education in the United Kingdom.[94] The Glasgow School, which developed in the late 19th century, and flourished in the early 20th century, produced a distinctive blend of influences including the Celtic Revival the Arts and Crafts Movement, and Japonisme, which found favour throughout the modern art world of continental Europe and helped define the Art Nouveau style. Among the most prominent members were the loose collective of The Four: acclaimed architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh, his wife the painter and glass artist Margaret MacDonald, her sister the artist Frances, and her husband, the artist and teacher Herbert MacNair.[95]

Scotland produced some of the most significant British architects of the 18th century, including: Colen Campbell (1676–1729), James Gibbs (1682–1754), James (1732–94), John (1721–92) and Robert Adam (1728–92) and William Chambers (1723–96), who all created work that to some degree looked to classical models. Edinburgh's New Town was the focus of this classical building boom in Scotland. From the mid-eighteenth century the it was laid out according to a plan of rectangular blocks with open squares, drawn up by James Craig. This classicism, together with its reputation as a major centre of the Enlightenment, resulted in the city being nicknamed "The Athens of the North".[96] However, the centralisation of much of the government administration, including the king's works, in London, meant that a number of Scottish architects spent most of all of their careers in England, where they had a major impact on Georgian architecture.[97]

Early 20th century

In the 20th century Scotland made a major contribution to the British participation in the two world wars and suffered relative economic decline, which only began to be offset with the exploitation of North Sea Oil and Gas from the 1970s and the development of new technologies and service industries. This was mirrored by a growing sense of cultural and political distinctiveness, which towards the end of the century, culminated in the establishment of a separate Scottish Parliament within the confines of the United Kingdom.

Before the First World War 1901–13

In the Khaki Election of 1900, nationalist concern with the Boer War meant that the Conservatives and their Liberal Unionist allies gained a majority of Scottish seats for the first time, although the Liberals regained their ascendancy in the next election. Various organisations, including the Independent Labour Party, joined to make the British Labour Party in 1906, with Keir Hardie as its first chairman.[98] The Unionists and Conservatives merged in 1912,[2] usually known as the Conservatives in England and Wales, they adopted the name Unionist Party in Scotland.[99]

The years before the First World War were the golden age of the inshore fisheries. Landings reached new heights, and Scottish catches dominated Europe's herring trade, accounting for a third of the British catch. High productivity came about thanks to the transition to more productive steam-powered boats, while the rest of Europe's fishing fleets were slower because they were still powered by sails.[100] However, in general the Scottish economy stagnated leading to growing unemployment and political agitation among industrial workers.[98]

First World War 1914–18

Scotland played a major role in the British effort in the First World War.[101] It especially provided manpower, ships, machinery, food (particularly fish) and money.[102] With a population of 4.8 million in 1911, Scotland sent 690,000 men to the war, of whom 74,000 died in combat or from disease, and 150,000 were seriously wounded.[103][104] Thus, although Scots were only 10 per cent of the British population, they made up 15 per cent of the national armed forces and eventually accounted for 20 per cent of the dead.[105] Concern for their families' standard of living made men hesitate to enlist; voluntary enlistment rates went up after the government guaranteed a weekly stipend for life to the survivors of men who were killed or disabled.[106] Clydeside shipyards and the engineering shops of west-central Scotland became the most significant centre of shipbuilding and arms production in the Empire. In the Lowlands, particularly Glasgow, poor working and living conditions led to industrial and political unrest.[105] After the end of the war in June 1919 the German fleet interned in Scapa Flow was scuttled by its crews, to avoid its ships being taken over by the victorious allies.[107]

Inter-war period 1919–38

After World War I the Liberal Party began to disintegrate. As the Liberals splintered Labour emerged to become the party of progressive politics in Scotland, gaining a solid following among working classes of the urban lowlands, and as a result the Unionists were able to gain most of the votes of the middle classes, who now feared Bolshevik revolution, setting the social and geographical electoral pattern in Scotland that would last until the late 20th century.[2] With all the main parties committed to the Union new nationalist and independent political groupings began to emerge, including the National Party of Scotland in 1928 and Scottish Party in 1930. They joined together to form the Scottish National Party (SNP) in 1934 with the goal of creating an independent Scotland, but it enjoyed little electoral success in the Westminster system.[108]

The interwar years were marked by economic stagnation in rural and urban areas, and high unemployment. Thoughtful Scots pondered their declension, as the main social indicators such as poor health, bad housing, and long-term mass unemployment, pointed to terminal social and economic stagnation at best, or even a downward spiral. The heavy dependence on obsolescent heavy industry and mining was a central problem, and no one offered workable solutions. The despair reflected what Finlay (1994) describes as a widespread sense of hopelessness that prepared local business and political leaders to accept a new orthodoxy of centralised government economic planning when it arrived during the Second World War.[109]

The shipbuilding industry had expanded by a third during the war and had expected continued prosperity, but instead it shrank drastically. A serious depression hit the economy by 1922 and it did not fully recover until 1939.[110] The most skilled craftsmen were especially hard hit, because there were few alternative uses for their specialised skills. The yards went into a long period of decline, interrupted only by the Second World War's temporary expansion.[111] The war had seen the emergence of a radical movement led by militant trades unionists. John MacLean became a key political figure in what became known as Red Clydeside, and in January 1919, the British Government, fearful of a revolutionary uprising, deployed tanks and soldiers in central Glasgow. Formerly a Liberal stronghold, the industrial districts switched to Labour by 1922, with a base in the Irish Catholic working class districts. Women were especially active in building neighbourhood solidarity on housing and rent issues. However, the "Reds" operated within the Labour Party and had little influence in Parliament; in the face of heavy unemployment the workers' mood changed to passive despair by the late 1920s.[112]

Emigration of young people continued apace with 400,000 Scots, ten per cent of the population, estimated to have left the country between 1921 and 1931.[113] The economic stagnation was only one factor; other push factors included a zest for travel and adventure, and the pull factors of better job opportunities abroad, personal networks to link into, and the basic cultural similarity of the United States, Canada, and Australia. Government subsidies for travel and relocation facilitated the decision to emigrate. Personal networks of family and friends who had gone ahead and wrote back, or sent money, prompted emigrants to follow.[114]

Scottish renaissance

In the early 20th century there was a new surge of activity in Scottish literature and art, influenced by modernism and resurgent nationalism, known as the Scottish Renaissance.[115] The leading figure in the movement was Hugh MacDiarmid (the pseudonym of Christopher Murray Grieve). MacDiarmid attempted to revive the Scots language as a medium for serious literature in poetic works including "A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle" (1936), developing a form of Synthetic Scots that combined different regional dialects and archaic terms.[115] Other writers that emerged in this period, and are often treated as part of the movement, include the poets Edwin Muir and William Soutar, the novelists Neil Gunn, George Blake, Nan Shepherd, A J Cronin, Naomi Mitchison, Eric Linklater and Lewis Grassic Gibbon, and the playwright James Bridie. All were born within a fifteen-year period (1887 and 1901) and, although they cannot be described as members of a single school they all pursued an exploration of identity, rejecting nostalgia and parochialism and engaging with social and political issues.[115]

In art, the first significant group to emerge in the 20th century were the Scottish Colourists in the 1920s: John Duncan Fergusson (1874–1961), Francis Cadell (1883–1937), Samuel Peploe (1871–1935) and Leslie Hunter (1877–1931).[116] Influenced by the Fauvists, they have been described as the first Scottish modern artists and were the major mechanism by which post-impressionism reached Scotland.[117] In the inter-war period, elements of modernism and the Scottish Renaissance, were incorporated into art by figures including Stanley Cursiter (1887–1976), who was influenced by Futurism, and William Johnstone (1897–1981), whose work marked a move towards abstraction.[118] Johnstone also played a part in developing the concept of a Scottish Renaissance with poet Hugh MacDiarmid, which attempted to introduce elements of modernism into Scottish cultural life and bring it into line with contemporary art elsewhere.[119] James McIntosh Patrick (1907–98) and Edward Baird (1904–) were influenced by elements of surrealism.[118]

Second World War 1939–45

.jpg)

The Second World War brought renewed prosperity, despite extensive bombing of cities by the Luftwaffe. It saw the invention of radar by Robert Watson-Watt, which was invaluable in the Battle of Britain, as was the leadership at RAF Fighter Command of Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding.[120]

As in World War I, Scapa Flow in Orkney served as an important Royal Navy base. Attacks on Scapa Flow and Rosyth gave RAF fighters their first successes downing bombers in the Firth of Forth and East Lothian.[121] The shipyards and heavy engineering factories in Glasgow and Clydeside played a key part in the war effort, and suffered attacks from the Luftwaffe, enduring great destruction and loss of life.[113] As transatlantic voyages involved negotiating north-west Britain, Scotland played a key part in the battle of the North Atlantic.[122] Shetland's relative proximity to occupied Norway resulted in the Shetland Bus by which fishing boats helped Norwegians fled the Nazis, and expeditions across the North Sea to assist resistance.[123] Perhaps Scotland's most unusual wartime episode occurred in 1941 when Rudolf Hess flew to Renfrewshire, possibly intending to broker a peace deal through the Duke of Hamilton.[124]

Scottish industry came out of the depression slump by a dramatic expansion of its industrial activity, absorbing unemployed men and many women as well. The shipyards were the centre of more activity, but many smaller industries produced the machinery needed by the British bombers, tanks and warships.[113] Agriculture prospered, as did all sectors except for coal mining, which was operating mines near exhaustion. Real wages, adjusted for inflation, rose 25 per cent, and unemployment temporarily vanished. Increased income, and the more equal distribution of food, obtained through a tight rationing system, dramatically improved the health and nutrition; the average height of 13-year-olds in Glasgow increased by 2 inches.[125]

Prime Minister Winston Churchill appointed Labour politician Tom Johnston as Secretary of State for Scotland in February 1941; he controlled Scottish affairs until the war ended. As Devine (1999) concludes, "Johnson was a giant figure in Scottish politics and is revered to this day as the greatest Scottish Secretary of the century ... in essence, Johnson was promised the powers of a benign dictator".[126] Johnston launched numerous initiatives to promote Scotland. Opposed to the excessive concentration of industry in the English Midlands, he attracted 700 businesses and 90,000 new jobs through his new Scottish Council of Industry. He set up 32 committees to deal with any number of social and economic problems, ranging from juvenile delinquency to sheep farming. He regulated rents, and set up a prototype national health service, using new hospitals set up in the expectation of large numbers of casualties from German bombing. His most successful venture was setting up a system of hydro electricity using water power in the Highlands.[127] A long-standing supporter of the Home Rule movement, Johnston persuaded Churchill of the need to counter the nationalist threat north of the border and created a Scottish Council of State and a Council of Industry as institutions to devolve some power away from Whitehall.[128]

Postwar 1946–present

Postwar politics

In this period the Labour Party usually won most Scottish parliamentary seats, losing this dominance briefly to the Unionists in the 1950s. Support in Scotland was critical to Labour's overall electoral fortunes as without Scottish MPs it would have gained only three UK electoral victories in the 20th century (1945, 1966 and 1997).[129] The number of Scottish seats represented by Unionists (known as Conservatives from 1965 onwards) went into steady decline from 1959 onwards, until it fell to zero in 1997.[130] The Scottish National Party gained its first seat at Westminster in 1945 and became a party of national prominence during the 1970s, achieving 11 MPs in 1974.[108] However, a referendum on devolution in 1979 was unsuccessful as it did not achieve the support of 40 per cent of the electorate (despite a small majority of those who voted supporting the proposal) and the SNP went into electoral decline during the 1980s.[108] The introduction in 1989 by the Thatcher-led Conservative government of the Community Charge (widely known as the Poll Tax), one year before the rest of the United Kingdom, contributed to a growing movement for a return to direct Scottish control over domestic affairs.[131] On 11 September 1997, the 700th anniversary of Battle of Stirling Bridge, the Blair-led Labour government again held a referendum on the issue of devolution. A positive outcome led to the establishment of a devolved Scottish Parliament in 1999.[132] The new Scottish Parliament Building, adjacent to Holyrood House in Edinburgh, opened in 2004.[133] The SNP won half of the Scottish vote with 50.0% in the 2015 UK General Election. It's best ever electoral result, eclipsing their previous 1970s peak in Westminster elections, the SNP also had success in the Scottish Parliamentary elections with their system of mixed member proportional representation. It became the official opposition in 1999, a minority government in 2007, a majority government from 2011 and a second minority government in 2016.[134]

Economics

After World War II, Scotland's economic situation became progressively worse due to overseas competition, inefficient industry, and industrial disputes.[135] This only began to change in the 1970s, partly due to the discovery and development of North Sea oil and gas and partly as Scotland moved towards a more service-based economy. The discovery of the giant Forties oilfield in October 1970 signalled that Scotland was about to become a major oil producing nation, a view confirmed when Shell Expro discovered the giant Brent oilfield in the northern North Sea east of Shetland in 1971. Oil production started from the Argyll field (now Ardmore) in June 1975, followed by Forties in November of that year.[136] Deindustrialisation took place rapidly in the 1970s and 1980s, as most of the traditional industries drastically shrank or were completely closed down. A new service-oriented economy emerged to replace traditional heavy industries.[137][138] This included a resurgent financial services industry and the electronics manufacturing of Silicon Glen.[139]

Twentieth-century religion

In the 20th century existing Christian denominations were joined by other organisations, including the Brethren and Pentecostal churches. Although some denominations thrived, after World War II there was a steady overall decline in church attendance and resulting church closures for most denominations.[18] In the 2011 census, 53.8% of the Scottish population identified as Christian (declining from 65.1% in 2001). The Church of Scotland is the largest religious grouping in Scotland, with 32.4% of the population. The Roman Catholic Church accounted for 15.9% of the population and is especially important in West Central Scotland and the Highlands. In recent years other religions have established a presence in Scotland, mainly through immigration and higher birth rates among ethnic minorities, with a small number of converts. Those with the most adherents in the 2011 census are Islam (1.4%, mainly among immigrants from South Asia), Hinduism (0.3%), Buddhism (0.2%) and Sikhism (0.2%). Other minority faiths include the Bahá'í Faith and small Neopagan groups. There are also various organisations which actively promote humanism and secularism, included within the 43.6% who either indicated no religion or did not state a religion in the 2011 census.[140]

Twentieth-century education

The Scottish education system underwent radical change and expansion in the 20th century. In 1918 Roman Catholic schools were brought into the system, but retained their distinct religious character, access to schools by priests and the requirement that school staff be acceptable to the Church. The school leaving age was raised to 14 in 1901, and although plans to raise it to 15 in the 1940s were never ratified, increasing numbers stayed on beyond elementary education and it was eventually raised to 16 in 1973. As a result, secondary education was the major area of growth in the inter-war period, particularly for girls, who stayed on in full-time education in increasing numbers throughout the century. New qualifications were developed to cope with changing aspirations and economics, with the Leaving Certificate being replaced by the Scottish Certificate of Education Ordinary Grade ('O-Grade') and Higher Grade ('Higher') qualifications in 1962, which became the basic entry qualification for university study. The centre of the education system also became more focused on Scotland, with the ministry of education partly moving north in 1918 and then finally having its headquarters relocated to Edinburgh in 1939.[70] After devolution, in 1999 the new Scottish Executive set up an Education Department and an Enterprise, Transport and Lifelong Learning Department, which together took over its functions.[141] One of the major diversions from practice in England, possible because of devolution, was the abolition of student tuition fees in 1999, instead retaining a system of means-tested student grants.[142]

New literature

.jpg)

Some writers that emerged after the Second World War followed MacDiarmid by writing in Scots, including Robert Garioch and Sydney Goodsir Smith. Others demonstrated a greater interest in English language poetry, among them Norman MacCaig, George Bruce and Maurice Lindsay.[115][143] George Mackay Brown from Orkney, and Iain Crichton Smith from Lewis, wrote both poetry and prose fiction shaped by their distinctive island backgrounds.[115] The Glaswegian poet Edwin Morgan became known for translations of works from a wide range of European languages. He was also the first Scots Makar (the official national poet), appointed by the inaugural Scottish government in 2004.[144] Many major Scottish post-war novelists, such as Muriel Spark, James Kennaway, Alexander Trocchi, Jessie Kesson and Robin Jenkins spent much or most of their lives outside Scotland, but often dealt with Scottish themes, as in Spark's Edinburgh-set The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961)[115] and Kennaway's script for the film Tunes of Glory (1956).[145] Successful mass-market works included the action novels of Alistair MacLean, and the historical fiction of Dorothy Dunnett.[115] A younger generation of novelists that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s included Shena Mackay, Alan Spence, Allan Massie and the work of William McIlvanney.[115]

From the 1980s Scottish literature enjoyed another major revival, particularly associated with a group of Glasgow writers focused around meetings in the house of critic, poet and teacher Philip Hobsbaum. Also important in the movement was Peter Kravitz, editor of Polygon Books. Members of the group that would come to prominence as writers included James Kelman, Alasdair Gray, Liz Lochhead, Tom Leonard and Aonghas MacNeacail.[115] In the 1990s major, prize-winning, Scottish novels that emerged from this movement included Irvine Welsh's Trainspotting (1993), Warner's Morvern Callar (1995), Gray's Poor Things (1992) and Kelman's How Late It Was, How Late (1994).[115] These works were linked by a sometimes overtly political reaction to Thatcherism that explored marginal areas of experience and used vivid vernacular language (including expletives and Scots dialect). Scottish crime fiction has been a major area of growth with the success of novelists including Val McDermid, Frederic Lindsay, Christopher Brookmyre, Quintin Jardine, Denise Mina and particularly the success of Edinburgh's Ian Rankin and his Inspector Rebus novels.[115] This period also saw the emergence of a new generation of Scottish poets that became leading figures on the UK stage, including Don Paterson, Robert Crawford, Kathleen Jamie and Carol Ann Duffy.[115] Glasgow-born Carol Ann Duffy was named as Poet Laureate in May 2009, the first woman, the first Scot and the first openly gay poet to take the post.[146]

Modern art

Important post-war artists included Anne Redpath (1895–1965), most famous for her two dimensional depictions of everyday objects,[147] Alan Davie (1920–), influenced by jazz and Zen Buddhism, who moved further into abstract expressionism[118] and sculptor and artist Eduardo Paolozzi (1924–2005), who was a pioneer of pop art and in a varied career produced many works that examined juxtapositions between fantasy and the modern world.[147] John Bellany (1942–), mainly focusing on the coastal communities of his birth and Alexander Moffat (1943–), who concentrated on portraiture, both grouped under the description of "Scottish realism", were among the leading Scottish intellectuals from the 1960s.[148] The artists associated with Moffat and the Glasgow School of Art are sometimes known as the "new Glasgow Boys", or "Glasgow pups"[149] and include Steven Campbell (1953–2007), Peter Howson (1958–), Ken Currie (1960–) and Adrian Wisniewski (1958–). Their figurative work has a comic book like quality and puts an emphasis on social commentary.[150] Since the 1990s, the most commercially successful artist has been Jack Vettriano, whose work usually consists of figure composition, with his most famous painting The Singing Butler (1992), often cited as the best selling print in Britain. However, he has received little acclaim from critics.[151] Contemporary artists emerging from the Glasgow include Douglas Gordon (1966–), working in the medium of installation art,[152] Susan Philipsz who works in sound installations, Richard Wright, noted for his intricate wall paintings[153] and Lucy McKenzie (1977–), whose painting is often sexually explicit.[154]

Notes

- Kelp was harvested from the seashore and burnt to produce minerals used in glassmaking.

References

- N. Davidson, The Origins of Scottish Nationhood (London: Pluto Press, 2000), ISBN 0-7453-1608-5, pp. 94–5.

- T. M. Devine and R. J. Finlay, Scotland in the Twentieth Century (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996), ISBN 0-7486-0839-7, pp. 64–5.

- M. Oaten, Coalition: the Politics and Personalities of Coalition Government from 1850 (London: Harriman House, 2007), ISBN 1-905641-28-1, pp. 37–40.

- F. Requejo and K-J Nagel, Federalism Beyond Federations: Asymmetry and Processes of Re-symmetrization in Europe (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2011),ISBN 1-4094-0922-8, p. 39.

- J. G. Kellas, "Unionists as nationalists", in W. Lockley, ed., Anglo-Scottish Relations from 1900 to Devolution and Beyond (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-19-726331-3, p. 52.

- K. Kumar, The Making of English National Identity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), ISBN 0-521-77736-4, p. 183.

- D. Howell, British Workers and the Independent Labour Party, 1888–1906 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984), ISBN 0-7190-1791-2, p. 144.

- T. M. Devine, The Scottish Nation, 1700–2000 (London: Penguin Books, 2001), ISBN 0-14-100234-4, pp. 84–89.

- A. Herman, How the Scots Invented the Modern World (London: Crown Publishing Group, 2001), ISBN 0-609-80999-7.

- José Manuel Barroso (28 November 2006), "The Scottish enlightenment and the challenges for Europe in the 21st century; climate change and energy", EUROPA: Enlightenment Lecture Series, Edinburgh University, archived from the original on 22 September 2007, retrieved 22 March 2012

- "The Scottish enlightenment and the challenges for Europe in the 21st century; climate change and energy", The New Yorker, 11 October 2004, archived from the original on 29 May 2011, retrieved 6 February 2016

- M. Magnusson (10 November 2003), "Review of James Buchan, Capital of the Mind: how Edinburgh Changed the World", New Statesman, archived from the original on 29 May 2011, retrieved 27 April 2014

- A. Swingewood, "Origins of Sociology: The Case of the Scottish Enlightenment," The British Journal of Sociology, vol. 21, no. 2 (June 1970), pp. 164–80 in JSTOR.

- M. Fry, Adam Smith's Legacy: His Place in the Development of Modern Economics (London: Routledge, 1992), ISBN 0-415-06164-4.

- J. Repcheck, The Man Who Found Time: James Hutton and the Discovery of the Earth's Antiquity (Cambridge, MA: Basic Books, 2003), ISBN 0-7382-0692-X, pp. 117–43.

- E. Wills, Scottish Firsts: a Celebration of Innovation and Achievement (Edinburgh: Mainstream, 2002), ISBN 1-84018-611-9.

- J. T. Koch, Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1–5 (London: ABC-CLIO, 2006), ISBN 1-85109-440-7, pp. 416–17.

- G. M. Ditchfield, The Evangelical Revival (Abingdon: Routledge, 1998), ISBN 1-85728-481-X, p. 91.

- T. A. Lee, Seekers of Truth: the Scottish Founders of Modern Public Accountancy (Bingley: Emerald Group, 2006), ISBN 0-7623-1298-X, pp. 23–4.

- Henry Hamilton, An Economic History of Scotland in the Eighteenth Century (1963).

- The Tobacco Lords: A study of the Tobacco Merchants of Glasgow and their Activities, Virginia Historical Society, JSTOR 4248011

- T. M. Devine, "The Colonial Trades and Industrial Investment in Scotland, c. 1700–1815," Economic History Review, Feb 1976, vol. 29 (1), pp. 1–13.

- R. H. Campbell, "The Anglo-Scottish Union of 1707. II: The Economic Consequences," Economic History Review, April 1964 vol. 16, pp. 468–477 in JSTOR.

- T. M. Devine, "An Eighteenth-Century Business Élite: Glasgow-West India Merchants, c 1750–1815," Scottish Historical Review, April 1978, vol. 57 (1), pp. 40–67.

- Louise Miskell and C. A. Whatley, "'Juteopolis' in the Making: Linen and the Industrial Transformation of Dundee, c. 1820–1850," Textile History, Autumn 1999, vol. 30 (2), pp. 176–98.

- Alastair J. Durie, "The Markets for Scottish Linen, 1730–1775," Scottish Historical Review vol. 52, no. 153, Part 1 (April 1973), pp. 30–49 in JSTOR.

- Alastair Durie, "Imitation in Scottish Eighteenth-Century Textiles: The Drive to Establish the Manufacture of Osnaburg Linen," Journal of Design History, 1993, vol. 6 (2), pp. 71–6.

- C. A. Malcolm, The History of the British Linen Bank (1950).

- R. Saville, Bank of Scotland: a History, 1695–1995 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press 1996), ISBN 0-7486-0757-9.

- M. J. Daunton, Progress and Poverty: An Economic and Social History of Britain 1700–1850 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), ISBN 0-19-822281-5, p. 344.

- T. Cowen and R. Kroszner, "Scottish Banking before 1845: A Model for Laissez-Faire?", Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, vol. 21, (2), (May 1989), pp. 221–31 in JSTOR.

- W. O. Henderson, The Lancashire Cotton Famine 1861–65 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1934), p. 122.

- C. A. Whatley, The Industrial Revolution in Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), ISBN 0-521-57643-1, p. 51.

- C. A. Whatley, "Scottish 'collier serfs', British coal workers? Aspects of Scottish collier society in the eighteenth century", Labour History Review, Fall 1995, vol. 60 (2), pp. 66–79.

- A. Campbell, The Scottish Miners, 1874–1939 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000), ISBN 0-7546-0191-9.

- C. F. Marshall, A History of Railway Locomotives Until 1831 (1926, BoD – Books on Demand, 2010), ISBN 3-86195-239-4, p. 223.

- O. Checkland and S. G. Checkland, Industry and Ethos: Scotland, 1832–1914 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 1989), ISBN 0-7486-0102-3, pp. 17–52.

- W. Vamplew, "Railways and the Transformation of the Scottish Economy", Economic History Review, Feb 1971, vol. 24 (1), pp. 37–54.

- William Ferguson, The Identity of the Scottish Nation: An Historic Quest (1998) online edition.

- I.H. Adams, The Making of Urban Scotland (Croom Helm, 1978).

- J. F. MacKenzie, "The second city of the Empire: Glasgow – imperial municipality", in F. Driver and D. Gilbert, eds, Imperial Cities: Landscape, Display and Identity (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2003), ISBN 0-7190-6497-X, pp. 215–23.

- J. Shields, Clyde Built: a History of Ship-Building on the River Clyde (Glasgow: William MacLellan, 1949).

- C. H. Lee, Scotland and the United Kingdom: the Economy and the Union in the Twentieth Century (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1995), ISBN 0-7190-4101-5, p. 43.

- J. Melling, "Employers, industrial housing and the evolution of company welfare policies in Britain's heavy industry: west Scotland, 1870–1920", International Review of Social History, Dec 1981, vol. 26 (3), pp. 255–301.

- R. C. Ray, Highland Heritage: Scottish Americans in the American South (UNC Press Books, 2001), ISBN 0-8078-4913-8, p. 41.

- J. L. Roberts, The Jacobite Wars: Scotland and the Military Campaigns of 1715 and 1745 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2002), ISBN 1-902930-29-0, pp. 193–5.

- Marco Sievers (October 2007). The Highland Myth as an Invented Tradition of 18th and 19th Century and Its Significance for the Image of Scotland. GRIN Verlag. pp. 22–25. ISBN 978-3-638-81651-9.

- P. Morère, Scotland and France in the Enlightenment (Bucknell University Press, 2004), ISBN 0-8387-5526-7, pp. 75–6.

- William Ferguson (1998). The Identity of the Scottish Nation: An Historic Quest. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-7486-1071-6.

- Norman C Milne (May 2010). Scottish Culture and Traditions. Paragon Publishing. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-899820-79-5.

- Devine, T M (2018). The Scottish Clearances: A History of the Dispossessed, 1600–1900. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0241304105.

- Richards, Eric (2000). The Highland Clearances People, Landlords and Rural Turmoil (2013 ed.). Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited. ISBN 978-1-78027-165-1.

- Richards, Eric (1985). A History of the Highland Clearances, Volume 2: Emigration, Protest, Reasons. Beckenham, Kent and Sydney, Australia: Croom Helm Ltd. ISBN 978-0709922599.

- Devine, T M (2006). Clearance and Improvement: Land, Power and People in Scotland, 1700–1900. Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd. ISBN 978-1-906566-23-4.

- McLean, Marianne (1991). The People of Glengarry: Highlanders in Transition, 1745-1820. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773511569.

- Lynch, Michael (1991). Scotland, a New History (1992 ed.). London: Pimlico. ISBN 9780712698931.

- Devine, T M (1994). Clanship to Crofters' War: The social transformation of the Scottish Highlands (2013 ed.). Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-9076-9.

- Devine, T M (1995). The Great Highland Famine: Hunger, Emigration and the Scottish Highlands in the Nineteenth Century. Edinburgh: Birlinn Limited. ISBN 1 904607 42 X.

- T. M. Divine (1999), The Scottish Nation, Viking, ISBN 0-670-88811-7

- J. Hunter (1974), "The Emergence of the Crofting Community: The Religious Contribution 1798–1843", Scottish Studies, 18: 95–111

- I. Bradley (December 1987), "'Having and Holding': The Highland Land War of the 1880s", History Today, 37: 23–28

- Ewen A. Cameron (June 2005), "Communication or Separation? Reactions to Irish Land Agitation and Legislation in the Highlands of Scotland, c. 1870–1910", English Historical Review, 120: 633–66, doi:10.1093/ehr/cei124

- A. K. Cairncross, The Scottish Economy: A Statistical Account of Scottish Life by Members of the Staff of Glasgow University (Glasgow: Glasgow University Press, 1953), p. 10.

- R. A. Houston and W. W. Knox, eds, The New Penguin History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 2001), ISBN 0-14-026367-5, p. xxxii.

- J. H. Morrison, John Witherspoon and the Founding of the American Republic (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2005).

- J. M. Bunsted, "Scots", Canadian Encyclopedia, archived from the original on 27 May 2011, retrieved 20 September 2017

- M. D. Prentis, The Scots in Australia (Sydney NSW: UNSW Press, 2008), ISBN 1-921410-21-3.

- "Scots", Te Ara, archived from the original on 27 May 2011, retrieved 22 November 2011

- "School education prior to 1873", Scottish Archive Network, 2010, archived from the original on 2 July 2011, retrieved 1 November 2013

- R. Anderson, "The history of Scottish Education pre-1980", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, Scottish Education: Post-Devolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1625-X, pp. 219–28.

- T. M. Devine, The Scottish Nation, 1700–2000 (London: Penguin Books, 2001), ISBN 0-14-100234-4, pp. 91–100.

- "Education records", National Archive of Scotland, 2006, archived from the original on 2 July 2011, retrieved 18 November 2011

- Paul L. Robertson, "The Development of an Urban University: Glasgow, 1860–1914", History of Education Quarterly, Winter 1990, vol. 30 (1), pp. 47–78.

- J. Buchan (2003), Crowded with Genius, Harper Collins, p. 311, ISBN 0060558881

- J. Buchan (2003), Crowded with Genius, Harper Collins, p. 163, ISBN 0060558881

- D. Thomson (1952), The Gaelic Sources of Macpherson's "Ossian", Aberdeen: Oliver & Boyd

- L. McIlvanney (Spring 2005), "Hugh Blair, Robert Burns, and the Invention of Scottish Literature", Eighteenth-Century Life, 29 (2): 25–46, doi:10.1215/00982601-29-2-25

- K. S. Whetter (2008), Understanding Genre and Medieval Romance, Ashgate, p. 28, ISBN 0754661423

- N. Davidson (2000), The Origins of Scottish Nationhood, Pluto Press, p. 136, ISBN 0745316085

- "Cultural Profile: 19th and early 20th century developments", Visiting Arts: Scotland: Cultural Profile, archived from the original on 5 November 2011

- J. Wormald (2005). Scotland: A History. OUP Oxford. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-19-162243-4.

- I. Baudino, "Aesthetics and Mapping the British Identity in Painting", in A. Müller and I. Karremann, ed., Mediating Identities in Eighteenth-Century England: Public Negotiations, Literary Discourses, Topography (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2011), ISBN 1409426181, p. 153.

- "Alan Ramsey", Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved 7 May 2012.

- "Gavin Hamilton", Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved 7 May 2012.

- I. Chilvers, ed., The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., 2009), ISBN 019953294X, p. 554.

- The Houghton Mifflin Dictionary of Biography (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2003), ISBN 061825210X, pp. 34–5.

- C. W. J. Withers, Geography, Science and National Identity: Scotland Since 1520 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), ISBN 0521642027, pp. 151–3.

- E. K. Waterhouse, Painting in Britain, 1530 to 1790 (Yale University Press, 5th edn., 1994), ISBN 0300058330, p. 293.

- C. C. Ochterbeck, ed., Michelin Green Guide: Great Britain Edition (Michelin, 5th edn., 2007), ISBN 1906261083, p. 84.

- I. Chilvers, ed., The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., 2009), ISBN 019953294X, p. 433.

- D. Kemp, The Pleasures and Treasures of Britain: A Discerning Traveller's Companion (Dundurn, 1992), ISBN 1550021591, p. 401.

- L. A. Rose, M. Macaroon, V. Crow, Frommer's Scotland (John Wiley & Sons, 12th edn., 2012), ISBN 1119992761, p. 23.

- F. M. Szasz, Scots in the North American West, 1790–1917 (University of Oklahoma Press, 2000), ISBN 0806132531, p. 136.

- I. Chilvers, ed., The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., 2009), ISBN 019953294X, p. 195.

- S. Tschudi-Madsen, The Art Nouveau Style: a Comprehensive Guide (Courier Dover, 2002), ISBN 0486417948, pp. 283–4.

- "Old and New Towns of Edinburgh – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. 20 November 2008. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- M. Glendinning, R. MacInnes and A. MacKechnie, A History of Scottish Architecture: from the Renaissance to the Present Day (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2002), ISBN 978-0-7486-0849-2, p. 73.

- J. Hearn, Claiming Scotland: National Identity and Liberal Culture (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2000), ISBN 1-902930-16-9, p. 45.

- L. Bennie, J. Brand and J. Mitchell, How Scotland Votes (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997), ISBN 0-7190-4510-X, p. 60.

- C. Reid, "Intermediation, Opportunism and the State Loans Debate in Scotland's Herring Fisheries before World War I," International Journal of Maritime History, June 2004, vol. 16 (1), pp. 1–26.

- C. M. M. Macdonald and E. W. McFarland, eds, Scotland and the Great War (Edinburgh: Tuckwell Press, 1999), ISBN 1-86232-056-X.

- D. Daniel, "Measures of enthusiasm: new avenues in quantifying variations in voluntary enlistment in Scotland, August 1914 – December 1915", Local Population Studies, Spring 2005, Issue 74, pp. 16–35.

- I. F. W. Beckett and K. R. Simpson, eds. A Nation in Arms: a Social Study of the British Army in the First World War (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1985), ISBN 0-7190-1737-8, p. 11.

- R. A. Houston and W. W. Knox, eds, The New Penguin History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 2001), ISBN 0-14-026367-5, p. 426.

- J. Buchanan, Scotland (Langenscheidt, 3rd edn., 2003), ISBN 981-234-950-2, p. 49.

- D. Coetzee, "A life and death decision: the influence of trends in fertility, nuptiality and family economies on voluntary enlistment in Scotland, August 1914 to December 1915", Family and Community History, Nov 2005, vol. 8 (2), pp. 77–89.

- E. B. Potter, Sea Power: a Naval History (Naval Institute Press, 2nd edn., 1981), ISBN 0-87021-607-4, p. 231.

- C. Cook and J. Stevenson, The Longman Companion to Britain since 1945 (Pearson Education, 2nd edn., 2000), ISBN 0-582-35674-1, p. 93.

- R. J. Finlay, "National identity in crisis: politicians, intellectuals and the 'end of Scotland', 1920–1939," History, June 1994, vol. 79, (256), pp. 242–59.

- N. K. Buxton, "Economic growth in Scotland between the Wars: the role of production structure and rationalization", Economic History Review, Nov 1980, vol. 33 (4), pp. 538–55.

- A. J. Robertson, "Clydeside revisited: A reconsideration of the Clyde shipbuilding industry 1919–1938" in W. H. Chaloner and B. M. Ratcliffe, eds., Trade and Transport: Essays in Economic History in Honour of T. S. Willan (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1977), ISBN 0-8476-6013-3, pp. 258–78.

- I. McLean, The Legend of Red Clydeside (1983, rpt, J. Donald, 2000), ISBN 0-85976-516-4.

- J. Buchanan, Scotland (Langenscheidt, 3rd edn., 2003), ISBN 981-234-950-2, p. 51.

- A. McCarthy, "Personal Accounts of Leaving Scotland, 1921–1954", Scottish Historical Review,' Oct 2004, vol. 83 (2), Issue 216, pp. 196–215.

- "The Scottish 'Renaissance' and beyond", Visiting Arts: Scotland: Cultural Profile, archived from the original on 5 November 2011

- "The Scottish Colourists", Visit Scotland.com, archived from the original on 29 April 2008, retrieved 7 May 2010

- I. Chilvers, ed., The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 4th edn., 2009), ISBN 019953294X, p. 575.

- M. Gardiner, Modern Scottish Culture (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), ISBN 0748620273, p. 173.

- D. Macmillan, "Review: Painters in Parallel: William Johnstone & William Gillies", Scotsman.com, 19 January 2012, retrieved 8 May 2012.

- R. Finlay, Modern Scotland: 1914–2000 (London: Profile Books, 2004), ISBN 1-86197-308-X, pp. 162–97.

- P. Wykeham, Fighter Command (Manchester: Ayer, rpt., 1979), ISBN 0-405-12209-8, p. 87.

- J. Creswell, Sea Warfare 1939–1945 (Berkeley, University of California Press, 2nd edn., 1967), p. 52.

- D. Howarth, The Shetland Bus: A WWII Epic of Escape, Survival, and Adventure (Guilford, DE: Lyons Press, 2008), ISBN 1-59921-321-4.

- J. Leasor Rudolf Hess: The Uninvited Envoy (Kelly Bray: House of Stratus, 2001), ISBN 0-7551-0041-7, p. 15.

- T. M. Devine, The Scottish Nation, 1700–2000 (London: Penguin Books, 2001), ISBN 0-14-100234-4, pp. 549–50.

- T. M. Devine, The Scottish Nation, 1700–2000 (London: Penguin Books, 2001), ISBN 0-14-100234-4, pp. 551–2.

- T. M. Devine, The Scottish Nation, 1700–2000 (London: Penguin Books, 2001), ISBN 0-14-100234-4, pp. 553–4.

- G. Walker, Thomas Johnston (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988), ISBN 0-7190-1997-4, pp. 153 and 174.

- L. Bennie, J. Brand and J. Mitchell, How Scotland Votes (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997), ISBN 0-7190-4510-X, p. 46.

- S. Ball and I. Holliday, Mass Conservatism: the Conservatives and the Public Since the 1880s (Abdingdon: Routledge, 2002), ISBN 0-7146-5223-7, p. 33.

- "The poll tax in Scotland 20 years on", BBC News, 1 April 2009, archived from the original on 28 May 2011, retrieved 19 November 2011

- "Devolution to Scotland", BBC News, 14 October 2002, archived from the original on 28 May 2011, retrieved 14 November 2006

- "The New Scottish Parliament at Holyrood" (PDF). Audit Scotland, Sep 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 10 December 2006.

- A. Black (18 May 2011), "Scottish election: SNP profile", BBC News, archived from the original on 4 June 2011, retrieved 21 June 2018

- W. Knox, Industrial Nation: Work, Culture and Society in Scotland, 1800–Present (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1999), ISBN 0-7486-1085-5, p. 255.

- J. Vickers and G. Yarrow, Privatization: an Economic Analysis (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 6th edn., 1995), ISBN 0-262-72011-6, p. 317.

- P. L. Payne, "The end of steelmaking in Scotland, c. 1967–1993", Scottish Economic and Social History, 1995, vol. 15 (1), pp. 66–84.

- R. Finlay, Modern Scotland: 1914–2000 (London: Profile Books, 2004), ISBN 1-86197-308-X, ch. 9.

- H. Stewart (6 May 2007), "Celtic Tiger Burns Brighter at Holyrood", Guardian.co.uk, archived from the original on 28 May 2011, retrieved 25 April 2008

- "Religion (detailed)" (PDF). Scotland's Census 2011. National Records of Scotland. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- J. Fairley, "The Enterprise and Lifelong Learning Department and the Scottish Parliament", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, Scottish Education: Post-Devolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1625-X, pp. 132–40.

- D. Cauldwell, "Scottish Higher Education: Character and Provision", in T. G. K. Bryce and W. M. Humes, eds, Scottish Education: Post-Devolution (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2nd edn., 2003), ISBN 0-7486-1625-X, pp. 62–73.

- P. Kravitz (1999), Introduction to The Picador Book of Contemporary Scottish Fiction, Ted Smart, p. xxvii, ISBN 0-330-33550-2

- The Scots Makar, The Scottish Government, 16 February 2004, archived from the original on 5 November 2011, retrieved 28 October 2007

- Royle, Trevor (1983), James & Jim: a Biography of James Kennaway, Mainstream, pp. 185–95, ISBN 978-0-906391-46-4

- "Duffy reacts to new Laureate post", BBC News, 1 May 2009, archived from the original on 5 November 2011

- L. A. Rose, M. Macaroon and V. Crow, Frommer's Scotland (John Wiley & Sons, 12th edn., 2012), ISBN 1119992761, p. 25.