Flora of Scotland

The flora of Scotland is an assemblage of native plant species including over 1,600 vascular plants, more than 1,500 lichens and nearly 1,000 bryophytes. The total number of vascular species is low by world standard but lichens and bryophytes are abundant and the latter form a population of global importance. Various populations of rare fern exist, although the impact of 19th-century collectors threatened the existence of several species. The flora is generally typical of the north west European part of the Palearctic realm and prominent features of the Scottish flora include boreal Caledonian forest (much reduced from its natural extent), heather moorland and coastal machair.[1] In addition to the native varieties of vascular plants there are numerous non-native introductions, now believed to make up some 43% of the species in the country.[2][3]

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_822246.jpg)

There are a variety of important trees species and specimens; a Grand Fir in Argyll is the tallest tree in the United Kingdom and the Fortingall Yew may be the oldest tree in Europe. The Arran Whitebeams, Shetland Mouse-ear and Scottish Primrose are endemic flowering plants and there are a variety of endemic mosses and lichens. Conservation of the natural environment is well developed and various organisations play an important role in the stewardship of the country's flora. Numerous references to the country's flora appear in folklore, song and poetry.

Habitats

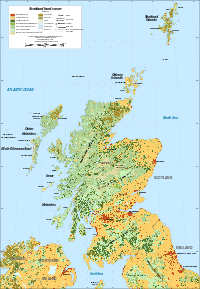

Scotland enjoys a diversity of temperate ecologies, incorporating both deciduous and coniferous woodlands, and moorland, montane, estuarine, freshwater, oceanic, and tundra landscapes.[4] Approximately 14% of Scotland is wooded, much of it forestry plantations, but prior to human clearing there would have been much larger areas of boreal Caledonian and broad-leaved forest.[5] Although much reduced, significant remnants of the native Scots Pine woodlands can be found in places.[6] Seventeen percent of Scotland is covered by heather moorland and peatland. Caithness and Sutherland have some of the largest and most intact areas of blanket bog in the world, supporting a distinctive wildlife community.[7][8] Seventy-five percent of Scotland's land is classed as agricultural (including some moorland) with urban areas accounting for around 3% of the total. The number of islands with terrestrial vegetation is nearly 800, about 600 of them lying off the west coast. Scotland has more than 90% of the volume and 70% of the total surface area of fresh water in the United Kingdom. There are more than 30,000 freshwater lochs and 6,600 river systems.[4]

Below the tree line there are several zones of climax forest. Birch dominates to the west and north, Scots Pine with Birch and oak in the eastern Highlands and oak (both Quercus robur and Q. petrea) with Birch in the Central Lowlands and Borders.[9] Much of the Scottish coastline consists of machair, a fertile dune pasture land formed as sea levels subsided after the last ice age. Machairs have received considerable ecological and conservational attention, chiefly because of their unique ecosystems.[10]

Flowering plants and shrubs

The total number of vascular species is low by world standards, partly due to the effects of Pleistocene glaciations (which eliminated all or nearly all species) and the subsequent creation of the North Sea (which created a barrier to re-colonisation).[1][11] Nonetheless, there are a variety of important species and assemblages. Heather moor containing Ling, Bell Heather, Cross-leaved Heath, Bog Myrtle and fescues is generally abundant and contains various smaller flowering species such as Cloudberry and Alpine Ladies-mantle.[12] Cliffs and mountains host a diversity of arctic and alpine plants including Alpine Pearlwort, Mossy Cyphal, Mountain Avens and Fir Clubmoss.[13] On the Hebridean islands of the west coast, there are plantago pastures, which grow well in locations exposed to sea spray and include Red Fescue, Sea Plantain and Sea Pink.[14] The machair landscapes include rare species such as Irish Lady's Tresses, Yellow Rattle and numerous orchids[10] along with more common species such as Marram and Buttercup, Ragwort, Bird's-foot Trefoil and Ribwort Plantain.[15] Scots Lovage, (Ligusticum scoticum) first recorded in 1684 by Robert Sibbald, and the Oyster Plant are common plants of the coasts.[16]

Aquatic species

Bogbean and Water Lobelia are common plants of moorland pools and lochans.[17] The Least (Nuphar pumila), Yellow and White Water-lilies are also widespread.[18] Pipewort has generated some botanical controversy regarding its discovery, classification and distribution. It was found growing on Skye in the 18th century, although there was subsequent confusion as to both the discoverer and the correct scientific name – now agreed to be Eriocaulon aquaticum. The European range of this plant is confined to Scotland and western Ireland and it is one of only a small number of species which is common in North America, but very restricted in Europe.[19] There are a few localised examples of the Rigid Hornwort (Ceratophyllum demersum).[20]

Grasses and sedges

Grasses and sedges are common everywhere except dune systems (where marram grass may be locally abundant) and stony mountain tops and plateaux. The total number of species is large, 84 have been recorded on the verges of a single road in West Lothian.[21] Smooth Meadow-grass and Broad-leaved Meadow-grass are widespread in damp lowland conditions, Wood Sedge (Carex sylvatica) in woodlands, and Oval Sedge and Early Hair-grass on upland moors.[22] In damp conditions Phragmites reeds[23] and several species of Juncus are found abundantly including Jointed Rush, Soft Rush and Toad Rush, and less commonly the introduced species Slender Rush.[24] Common Cottongrass is a familiar site on marshy land,[25] but Saltmarsh Sedge (Carex salina) was only discovered for the first time in 2004 at the head of Loch Duich.[26]

Endemic species

Shetland Mouse-ear (Cerastium nigrescens) is an endemic plant found in Shetland. It was first recorded in 1837 by Shetland botanist Thomas Edmondston. Although reported from two other sites in the 19th century, it currently grows only on two serpentine hills on the island of Unst.[27][28]

The Scottish Primrose (Primula scotica), is endemic to the north coast including Caithness and Orkney. It is closely related to the Arctic species Primula stricta and Primula scandinavica.[29][30]

Young's Helleborine (Epipactis youngiana) is a rare endemic orchid principally found on bings created by the coal-mining industry in the Central Lowlands and classified as endangered.[31][32]

The St Kilda Dandelion (Taraxacum pankhurstianum) is a species of dandelion endemic to the island of Hirta, identified in 2012.[33]

Rare species

Some of Scotland's flowering plant species have extremely restricted ranges in the country. These include Diapensia lapponica, found only on the slopes of Sgurr an Utha, Argyll[34] and Mountain Bearberry, recorded at only a few mainland locations, and on Skye and Orkney.[35] The pinewoods of Strathspey contain rare species such as Creeping Lady's Tresses, Twinflower and the One-flowered Wintergreen. Plans to protect the Intermediate Wintergreen, also found here, were introduced in 2008.[36][37] Other nationally rare species include Tufted Saxifrage, Alpine Catchfly, Sword-leaved Helleborine, Norwegian Sandwort, Dark-red Helleborine, Iceland Purslane, Small Cow-wheat and Yellow Oxytropis.[38][39][40][41]

Invasive plants

A number of non-native, invasive species have been identified as a threat to native biodiversity, including Giant Hogweed, Japanese Knotweed and Rhododendron. In May 2008 it was announced that psyllid lice from Japan, which feed on the Knotweed, may be introduced to the UK to bring the plant under control. This would be the first time that an alien species has been used in Britain in this way. Scientists at the Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux International do not believe the lice will cause any environmental damage.[42] Over-grazing caused by the large numbers of Red Deer and sheep has also resulted in the impoverishment of moorland and upland habitats and a loss of native woodland.[43]

Deciduous trees

Only thirty-one species of deciduous tree and shrub are native to Scotland, including 10 willows, four whitebeams and three birch and cherry species.[44]

The Meikleour Beech hedges located in Perth and Kinross were planted in the autumn of 1745 by Jean Mercer and her husband, Robert Murray Nairne. This European Beech hedge, which is 530 metres (0.3 miles) in length, reaches 30 metres (100 ft) in height and is noted in the Guinness World Records as the tallest and longest hedge on Earth.[45][46]

The Arran Whitebeams are species unique to the Isle of Arran. The Arran Whitebeam (Sorbus arranensis) and the Cut-leaved Whitebeam (S. pseudofennica) are amongst the most endangered tree species in the world if rarity is measured by numbers alone. Only 236 S. pseudofennica and 283 S. arranensis were recorded as mature trees in 1980.[47][48] The trees developed in a highly complex fashion involving the Rock Whitebeam (S. rupicola), which is found on nearby Holy Isle but not Arran, interbreeding with the Rowan (S. aucuparia) to produce the new species. In 2007 it was announced that two specimens of a third new hybrid, the Catacol Whitebeam (S. pseudomeinichii) had been discovered by researchers on Arran. This tree is a cross between the native Rowan and S. pseudofennica.[49]

Shakespeare makes reference to Birnam Wood being used as camouflage for Malcolm Canmore’s army before the battle at Dunsinane with MacBeth. There is an ancient tree, the Birnam Oak, standing a few hundred metres from the centre of Birnam. It may well have been part of Birnam Wood at the time of the battle 900 years ago, and remains part of the legend.[50][51]

Research into the possible commercial use of Sea Buckthorn was undertaken by Moray College commencing in 2006. The orange berries can be processed into jams, liquors and ointments and the hardy species grows well even on exposed west coasts.[52]

Conifers

The Scots Pine and Common Juniper are the only coniferous trees definitely native to Scotland with Yew a possible contender.[44]

The Fortingall Yew is an ancient tree in the churchyard of the village of Fortingall in Perthshire. Various estimates have put its age at between 2,000 and 5,000[53] years; recent research into yew tree ages[54][55] suggests that it is likely to be nearer the lower limit of 2,000 years. This still makes it the oldest tree in Europe, although there is an older Norway Spruce root system in Sweden.[56][57]

At 64.3 metres (211 ft), a Grand Fir planted beside Loch Fyne, Argyll in the 1870s was named as the UK’s tallest tree in 2011.[58] The next four tallest trees in the UK are all found in Scotland. The Stronardron Douglas Fir which grows near Dunans Castle in Argyll is recorded as 63.79 metres (209.3 ft). Diana’s Grove Grand Fir at Blair Castle, which was measured at 62.7 metres (206 ft) is the next highest. Dùghall Mòr (Scottish Gaelic for "Big Douglas"), another Douglas Fir located in Reelig Glen near Inverness, reaches just over 62 metres (203 ft) in height and was considered to be the tallest tree in Britain until a survey undertaken by Sparsholt College in 2009 (which named the Stronardron fir as the highest). This survey concluded that the Hermitage Douglas Fir near Dunkeld came next in height, standing at 61.31 metres (201 ft).[59][60]

Ferns

Bracken is very common in upland areas, Beech Fern in woods and other shaded locations and Scaly Male Fern in wooded or open areas.[61] Wilsons Filmy-fern is a common upland variety in the Highlands, along with the Tunbridge Filmy-fern, Alpine Lady-fern and the rarer stunted form Newman’s Lady-fern (A. distentifolium var. flexile) which is endemic to Scotland.[39][62][63] The Killarney Fern, once found on Arran was thought to be extinct in Scotland,[64] but has been discovered on Skye in its gametophyte form.[65]

Scotland's populations of Alpine Woodsia and Oblong Woodsia are on the edge of their natural ranges. The UK distribution of the former is confined to Angus, Perthshire, Argyll and north Wales, and of the latter to Angus, the Moffat Hills, north Wales and two locations in England. The plants were first identified as separate species by John Bolton in 1785 and came under severe threat from Victorian fern collectors in the mid 19th century.[66] Cystopteris dickieana, first discovered in a sea cave in Kincardineshire, is a rare fern in a UK context whose distribution is confined to Scotland, although recent research suggests that it may be a variant of C. fragilis rather than a species in its own right.[67][68]

Non-vascular plants

Scotland provides ideal growing conditions for many bryophyte species, due to the damp climate, absence of lengthy droughts and winters without protracted hard frosts. In addition, the country's diverse geology, numerous exposed rocky crags and screes and deep, damp ravines coupled with a relatively pollution-free atmosphere enables a diversity of species to exist. This unique assemblage is in marked contrast to the relative impoverishment of the native vascular plants.[69] There are about 920 species of moss and liverwort in Scotland, with 87% of UK and 60% of European bryophytes represented. Scotland's bryophyte flora is globally important and this small country may host as many as 5% of the world’s species (in 0.05% of the Earth's land area, similar in size to South Carolina or Assam). The mountains of the North-west Highlands host a unique bryophyte community called the "Northern Hepatic Mat", which is dominated by a variety of rare liverworts, such as Pleurozia purpurea and Anastrophyllum alpinum.[70][71]

Scotland has played an important part in the development of the understanding of bryology, with pioneers such as Archibald Menzies and Sir William Hooker commencing explorations at the end of the eighteenth century. Tetrodontium brownianum is named after Robert Brown who first discovered the plant growing at Roslin near Edinburgh and several other species such as Plagiochila atlantica and Anastrepta orcadensis were also first discovered in the country.[71]

Mosses

Sphagnum, is common and harvested commercially for use in hanging baskets and wreaths, and for medical purposes.[72] Glittering Wood-moss, Woolly Hair-moss (Racomitrium lanuginosum) and Bristly Haircap (Polytrichum piliferum) are amongst many other abundant natives.[73][74][75] Endemic species include the Scottish Thread-moss, Dixon’s Thread Moss and Scottish Beard-moss.[70][76] In the Cairngorms there are small stands of Snow Brook-moss and Alpine Thyme-moss, and an abundance of Icy Rock-moss, the latter's UK population being found only here and at one site in England.[77][78] The west coast is rich in oceanic mosses such as Cyclodictyon laetevirens and the Ben Lawers range also provides habitats for various rare species such as Tongue-leaved Gland Moss. Perthshire Beard-moss is a European endemic, occurring at only four European sites outside Scotland and it is classified as "Critically Endangered".[71][76]

Liverworts and hornworts

There are numerous common liverworts such as Conocephalum conicum and Marchantia polymorpha.[71][79] Autumn Flapwort (Jamesoniella autumnali), a nationally scarce species most commonly found in the sessile oak woods of western Scotland, was discovered at a site on Ben Lomond in 2008. The species is named after the Scottish botanist, William Jameson.[80] Northern prongwort is an endemic liverwort found only in the Beinn Eighe nature reserve.[81] The high Cairngorms provide sites for a variety of other unusual liverworts including Marsupella arctica, the European distribution of which is confined to two sites here and Svalbard.[77]

Hornworts are scarce in Scotland, Carolina Hornwort (Phaeoceros carolinianus) for example, having been found only in Lauderdale.[82]

Lichens

Lichens are abundant, with 37% of European species represented in just 0.75% of the European land area.[3] Most rock surfaces, except those in very exposed places, or that are kept constantly wet by sea or fresh water, become grown with lichens. Reindeer Moss (Cladonia rangiferina) is a common species. The trunks and branches of large trees are an important lichen habitat, Tree Lungwort being particularly conspicuous. In the past lichens were widely used for dyeing clothing.[83]

Graphis alboscripta and Halecania rhypodiza are endemic species. The former is found in the hazel woodlands of the west coast and the latter at only two sites in the Highlands.[84][85] The British ranges of 35 species are confined to the Cairngorm Mountains. These include Alectoria ochroleuca, Rinodian parasitica and Cladonia trassii. Other nationally rare species found here are Jamesiella scotica, Cladonia botrytes and Ramalina polymorpha.[86]

Conservation

Conservation of the natural environment is well developed in the United Kingdom. There are various public sector organisations with an important role in the stewardship of the country's flora. Scottish Natural Heritage is the statutory body responsible for natural heritage management in Scotland. One of their duties is to establish National Nature Reserves. Until 2004 there were 73, but a review carried out in that year resulted in a significant number of sites losing their NNR status, and as of 2006 there are 55.[87] Forestry and Land Scotland serves as the forestry department of the Scottish Government and is one of the country's largest landowners. The Joint Nature Conservation Committee is the statutory adviser to Government on UK and international nature conservation.

The country has two national parks. Cairngorms National Park includes the largest area of arctic mountain landscape in the UK. Sites designated as of importance to natural heritage take up 39% of the land area, two thirds of which are of Europe-wide importance.[88] Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park includes Britain's largest body of freshwater, the mountains of Breadalbane and the sea lochs of Argyll.

There are also numerous charitable and voluntary organisations with an important role to play, of which the more prominent include the following. The National Trust for Scotland is the conservation charity that protects and promotes Scotland's natural and cultural heritage. With over 270,000 members it is the largest conservation charity in Scotland. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds promotes conservation of birds and other wildlife through the protection and re-creation of habitats. The John Muir Trust is a charity whose main role is as a guardian of wild land and wildlife, through the ownership of land and the promotion of education and conservation. The trust owns and manages estates in various locations, including Knoydart, Assynt, and on the isle of Skye.[89] Trees for Life is a charity that aims to restore a "wild forest" in the Northwest Highlands and Grampian Mountains.[90]

Under the auspices of the European Unions Habitats Directive, as at 31 March 2003 a total of 230 sites in Scotland covering an area of 8,748.08 km2 (3,377.65 sq mi) had been submitted by the UK government to the European Commission as candidate Special Areas of Conservation (cSAC).[91]

The Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 prohibits the uprooting of plants without a landowner's permission and the collection of any part of the most threatened species, which are listed in Schedule 8. In 2012 the Scottish Government published a "Code of Practice on Non-Native Species" to help people understand their responsibilities and provide guidance as to which public body has responsibility for the various habitats involved.[92]

Flora in Scottish culture

Plants feature heavily in Gaelic and Scottish folklore, song and poetry.

The thistle has been one of the national emblem of the Scots nation since the reign of Alexander III (1249–1286) and was used on silver coins issued by James III in 1470.[93] Today, it forms part of the emblem of the Scottish Rugby Union. As legend has it, an invading army had attempted to sneak up at night on the Scots. One, perhaps barefooted, unwelcome foreign soldier stumbled upon a Scots Thistle, and cried out in pain, thus alerting Scots to their presence. Some sources suggest the specific occasion was the Battle of Largs, which marked the beginning of the departure of the Viking monarch Haakon IV of Norway, who had harried the coast for some years.[94] Spiky plants such as brambles appear to have been used around forts[95] since time immemorial, so the story, whether it factually relates to the Haakon episode or not, likely is the culmination of more than one such event over time. In some variants, it is invading English which stumble on a thistle, but the story predates this time.

Numerous plants are referred to in Scottish song and verse. These include Robert Burns A Red, Red Rose, Hugh MacDiarmid's A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle, Sorley MacLean's Hallaig,[96] Harry Lauder's I Love A Lassie and in the 21st century, Runrig's And The Accordions Played.[97] The last two lyrics include a reference to the bluebell. The "Scottish Bluebell" is Campanula rotundifolia, (known elsewhere as the "Harebell") rather than Hyacinthoides non-scripta, the "Common Bluebell".[98]

Trees held an important place in Gaelic culture from the earliest times. Particularly large trees were venerated, and the most valuable such as oak, Common Hazel and Apple were classed as "nobles". The less important Common Alder, Common Hawthorn and Gean were classed as "commoners", and there were "lower orders" and "slaves" such as Eurasian Aspen and Juniper. The alphabet was learned as a mnemonic using tree names. Rowan was regularly planted close to Highland houses as a protection from witchcraft.[99]

Various plants are said to have apotropaic qualities, notably Mountain Ash. Henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) may have been used as a hallucinogen as long ago as the Neolithic period.[100][101] This tradition has recently been taken up once again by New Agers.[102]

See also

- Botanical Society of Scotland

- Gardens in Scotland

- Category:Scottish botanists

- List of Scottish plants

- Category:Lists of the vascular plants of the British Isles

- List of the mosses of Britain and Ireland

- Fauna of Scotland

- Traditional dyes of the Scottish Highlands, many of which use plants.

- Forestry in Scotland

References

- Lusby, Phillip and Wright, Jenny (2002) Scottish Wild Plants: Their History, Ecology and Conservation. Edinburgh. Mercat. ISBN 1-84183-011-9

- Ratcliffe, Derek (1977) Highland Flora. Inverness. HIDB. ISBN 0-902347-56-X

- Shaw, Philip and Thompson, Des (eds.) (2006) The Nature of the Cairngorms: Diversity in a changing environment. Edinburgh. The Stationery Office. ISBN 0-11-497326-1.

- Smout, T.C. MacDonald, R. and Watson, Fiona (2007) A History of the Native Woodlands of Scotland 1500–1920. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-3294-7.

- Webster, Mary McCallum (1978) Flora of Moray, Nairn & East Inverness. Aberdeen University Press. ISBN 0-900015-42-X

Notes

- "Flowering Plants and Ferns" Archived 21 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine SNH. Retrieved 26 April 2008

- "Natural Heritage Trends. Species diversity: plant species" Archived 1 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine SNH. Retrieved 26 April 2008

- "LICHENS: Biodiversity & Conservation" RBGE. Retrieved 26 April 2008

- "Scottish wildlife habitats". Scottish Natural Heritage. Archived from the original on 22 December 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- Edlin, H.D. (1956). Trees, Woods and Man. London: Collins.

- Preston, C.D.; Pearman, D.A.; Dines, T.D. (2002). New Atlas of the British and Irish Flora. Oxford University Press.

- Ratcliffe, D.A. (7 October 1998). "Flow Country: The Peatlands of Caithness and Sutherland". JNCC. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "North Highland Peatlands". Scottish Natural Heritage. Archived from the original on 28 November 2005. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- Tivy, Joy "The Bio-climate" in Clapperton, Chalmers M. (ed.) (1983) Scotland: A New Study. Newton Abbott. David & Charles.

- "The Natural Environment: Machair" Wildlife Hebrides. Retrieved 25 April 2008 Archived 20 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Lusby and Wright (2001) p. 3.

- Ratcliffe (1977) pp. 37, 70.

- Slack, Alf "Flora" in Slesser, Malcolm (1970) The Island of Skye. Edinburgh. Scottish Mountaineering Club. pp 45–58.

- Fraser Darling, F., and Boyd, J.M. (1969) Natural History in the Highlands and Islands, London, Bloomsbury ISBN 1-870630-98-X

- Ratcliffe (1977) p. 100.

- Lusby and Wright (2001) p. 50.

- Ratcliffe (1977) pp. 50, 75.

- Lusby and Wright (2001) p. 69.

- Lusby and Wright (2001) pp. 42–3.

- Stace, Clive et al. "Ceratophyllum demersum" Archived 8 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Interactive Flora of NW Europe. Retrieved 15 May 2008.

- "Vegetation change on highway verges in south-east Scotland." JSTOR. Journal of Biogeoraphy. 13 pp. 109–107. Retrieved 5 June 2008.

- Webster (1978) pp. 469, 481–3, 497–98, 514.

- Webster (1978) p. 483.

- Webster (1978) pp. 435–41.

- Webster (1978) p. 460.

- "Search for sedge species starts". BBC News. 1 February 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- Scott, W. & Palmer, R. (1987) The Flowering Plants and Ferns of the Shetland Islands. Shetland Times. Lerwick.

- Scott, W. Harvey, P., Riddington, R. & Fisher, M. (2002) Rare Plants of Shetland. Shetland Amenity Trust. Lerwick.

- "Caithness plants: Primula scotica" caithness.org. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- Orkney Islands Council: "Where to see Primula scotica" Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine Orkney Islands Council. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- Lusby and Wright (2001) p. 8.

- This British red listed species is known from only six sites in the UK – five in Scotland and one in northern England. See "Species Action Plan: Young's Helleborine (Epipactis youngiana)" Archived 30 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine UK Biodiversity Action Plan. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- "New Dandelion Found". Royal Botanical Garden Edinburgh. Retrieved 29 June 2012.

- Grant Roger, J. (1952). "Diapensia lapponica in Scotland". Transactions of the Botanical Society of Scotland. 36: 34–37.

- Lusby and Wright (2001) pp. 22–3.

- "Experts join forces to halt decline of rare forest plant" (18 March 2008) Edinburgh. The Scotsman.

- "Twinflower" Archived 5 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine Trees for Life. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- Ratcliffe (1977) pp. 61, 90.

- Nazgy, Laszlo et al. "Vascular Plants", in Shaw and Thompson (2006) pp. 215–231.

- Lusby and Wright (2001) pp. 14, 48.

- "Small Cow-wheat distributions for Scotland 1999 to 2005" Archived 14 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine UK National Biodiversity Network, Scottish Wildlife Trust. Retrieved through GBIF data portal 17 July 2008.

- Johnston, Ian (5 May 2008) "Britain calls on alien parasites to take fight to Japanese knotweed". Edinburgh. The Scotsman.

- Skye & Lochalsh Biodiversity Action Plan Archived 11 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine (2003) (pdf) Skye and Lochalsh Biodiversity Group. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- Smout (2007) p. 2.

- "World's tallest hedge gets the chop!" Archived 8 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Scottish Natural Heritage. Retrieved 1 May 2008.

- "Meikleour Beech Hedge" Big Tree Country.co.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2008.

- Donald Rodger, John Stokes & James Ogilve (2006). Heritage Trees of Scotland. The Tree Council. p. 58. ISBN 0-904853-03-9.

- Eric Bignal (1980). "The endemic whitebeams of North Arran". The Glasgow Naturalist. 20 (1): 60–64.

- "Catacol whitebeam" BBC. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- "Birnam Oak" Big Tree Country. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- "The Birnam Oak Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Forestry Commission. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- Rollo, Sarah (5 January 2008) "Moray pioneers berry crop trials". Aberdeen. Press and Journal.

- "The Fortingall Yew" Archived 17 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Forestry Commission. Retrieved 1 May 2008.

- Harte, J. (1996) "How old is that old yew?" At the Edge 4: 1–9.

- Kinmonth, F. (2006). Ageing the yew – no core, no curve? International Dendrology Society Yearbook 2005: 41–46.

- "Oldest Living Tree Found in Sweden" National Geographic. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- "Wanted: Fat, old, gnarled trees" (28 June 2007) Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 29 September 2007. "The Fortingall Yew near Callendar in Scotland – believed to be the oldest tree in the UK and possibly Europe."

- Copping, Jasper (4 June 2011) "Britain's record-breaking trees identified" London. The Telegraph. Retrieved 10 July 2011. This source quotes Johnson, Owen (2011) Champion Trees of Britain and Ireland: The Tree Register Handbook. London. Kew Publishing but does not refer to the next tallest trees.

- "Scotland remains home to Britain's tallest tree as Dughall Mor reaches new heights" Archived 3 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Forestry Commission. Retrieved 26 April 2008

- "Scots fir is 'tallest tree in UK' " BBC NEWS. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Ratcliffe (1977) p. 9, 31, 50.

- Ratcliffe, (1977) pp. 40, 67.

- "Habitat account – Rocky habitats and caves: 8110 Siliceous scree of the montane to snow levels (Androsacetalia alpinae and Galeopsietalia ladani)". JNCC. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- Ratcliffe (1977) page 40.

- "Skye Flora". plant-identification.co.uk. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- Lusby and Wright (2001) pp. 107–09.

- Parks, J.C., Dyer, F.A. and Lindsay, S. (2000) "Allozyme, Spore and Frond Variation in Some Scottish Populations of the Ferns Cystopteris dickieana and Cystopteris fragilis". Edinburgh Journal of Botany 57: pp. 83–105. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- Lusby (2002) pp. 35–37.

- "Why Scotland has so many mosses and liverworts" SNH. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- "Mosses and Liverworts in Scotland" Archived 23 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine SNH. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- "Bryology (mosses, liverworts and hornworts)" Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Retrieved 15 May 2008.

- "Sphagnum moss (Sphagnum spp.)" ForestHarvest. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- Hobbs, V.J. and N. M. Pritchard (March 1987) "Population Dynamics of the Moss Polytrichum Piliferum in North-East Scotland". The Journal of Ecology 75 No. 1 pp. 177–192. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- "Hylocomium splendens: Mountain Fern Moss" Rook.Org. Retrieved 16 May 2008. Archived 22 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Species Profile: Glittering wood-moss" Archived 31 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine Trees for Life. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- "Moss Species Action Plan US8" Archived 4 September 2004 at the Wayback Machine (2001) (pdf) Stirling Council. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- Rothero, Gordon "Bryophytes", in Shaw and Thompson (2006) p. 200.

- Note that Moss is also the name given to substantial areas of bog in Scotland such as the Solway Moss. See for example An Account of the Mosses in Scotland. In a Letter from the Right Honourable George Earl of Cromertie, &c. Fellow of the Royal Society, to Dr. Hans Sloane, R. S. Secr., by George Earl of Cromertie Philosophical Transactions The Royal Society. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- Ratcliffe (1977) p.27.

- "Rare plant discovered on Ben Lomond". NTS. Retrieved 7 May 2008.

- David Bell & David Long (2012). "European Herbertus and the 'Viking prongwort'" (PDF). Field Bryology. 106: 3–14.

- "Return of the Hornworts" British Bryological Society. Retrieved 15 May 2008.

- Ratcliffe (1977) page 42.

- "Species & Habitat Detail" Biodiversity Scotland. Retrieved 5 July 2008. Archived 20 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Lichen Species Action Plan US6" Archived 8 September 2004 at the Wayback Machine. (pdf) Stirling Council. Retrieved 5 July 2008.

- Fryday, Alan "Lichens", in Shaw and Thompson (2006) pp. 177–90.

- "SNH Annual Review 2006" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- "The Park". CNPA. Archived from the original on 7 February 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2007.

- "Welcome to the John Muir Trust" Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- "Vision statement". Trees for Life. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 3 January 2007.

- "Trends: The Seas around Scotland". Scottish Natural Heritage. Archived from the original on 4 August 2004. Retrieved 26 April 2008. Quoting the Scottish Office. (1998). People and nature. A new approach to SSSI designations in Scotland. The Scottish Office, Edinburgh. Retrieved 2 January 2007.

- "Code of Practice on Non-Native Species" Scottish Government. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- Duncan, John A. "The story Behind the Scottish Thistle the national emblem of Scotland:'A Prickly Tale'." scotshistoryonline. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- Vandaveer, Chelsie (2003) "Why is thistle the emblem of Scotland?" Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine killerplants.com Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- Brice, M. (1999) Forts and Fortresses – From the Hill Forts of Prehistory to Modern Times: The Definitive Visual Account of the Science of Fortification. Chancellor Press. Retrieved 26 April 2008.

- Text of the poem in Gaelic, with Sorley Maclean's own translation into English Archived 21 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2 June 2007.

- From the 2007 album Everything You See. See "And The Accordions Played". Archived 17 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine jimwillsher.co.uk. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- Ratcliffe (1977) p. 63.

- Smout (2007) pp. 78–80.

- Barclay, G. J. and Russell-White, C. (1993) "Excavations in the ceremonial complex of the fourth to second millennium BC and Balfarg/Balbirnie, Glenrothes, Fife." Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 123 pp.43–210.

- Barclay and Russell-White's findings have been contested by Long, D. J. et al. (1999) "Black Henbane (Hyoscyamus niger L.) in the Scottish Neolithic: A Re-evaluation of Palynological Findings from Grooved Ware Pottery at Balfarg Riding School and Henge, Fife." Academic Press. Retrieved 28 April 2008.

- "The Rowan Tree" Celtic Society. Retrieved 26 April 2008.