Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland (CoS; Scots: The Scots Kirk; Scottish Gaelic: Eaglais na h-Alba), also known by its Scots language name, the Kirk, is the national church of Scotland.[3] It is Presbyterian, having no head of faith or leadership group, and adheres to the Bible and Westminster Confession; the Church of Scotland celebrates two sacraments, Baptism and the Lord's Supper, as well as five other rites, such as confirmation and matrimony.[4][5] It is a member of the World Communion of Reformed Churches.[6]

| Church of Scotland | |

|---|---|

Modern logo of the Church of Scotland | |

| Abbreviation | CoS |

| Classification | Protestant |

| Orientation | Calvinist |

| Theology | Calvinism |

| Polity | Presbyterian[1] |

| Associations | |

| Region | Scotland |

| Founder | John Knox |

| Origin | 1560 (Reformation Parliament) |

| Separated from | Roman Catholic Church |

| Absorbed |

|

| Separations |

|

| Congregations | 1,353 |

| Members |

|

| Official website | churchofscotland |

The Church of Scotland traces its roots back to the beginnings of Christianity in Scotland, but its identity is principally shaped by the Reformation of 1560. According to the Church of Scotland, in 2013 its membership was 398,389,[7] or about 7.5% of the total population, dropping to 380,164 by 2014,[8] 336,000 by 2017,[9] and 325,695 by 2018, representing about 6% of the Scottish population.[10]

According to the 2018 Household Survey, 22% of the Scottish population in 2018 (down from 34% in 2009) reported belonging to the Church of Scotland.[11] The church's motto is "Nec tamen consumebatur"

"'Yet it was not consumed" – Exodus 3:2

History

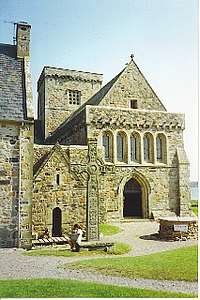

Presbyterian tradition, particularly that of the Church of Scotland, traces its early roots to the Church founded by Saint Columba, through the 6th century Hiberno-Scottish mission.[12][13][14] Tracing their apostolic origin to Saint John,[15][16] the Culdees practised Christian monasticism, a key feature of Celtic Christianity in the region, with a presbyter exercising "authority within the institution, while the different monastic institutions were independent of one another."[17][12][18] The Church in Scotland kept the Christian feast of Easter at a date different from the See of Rome and its monks used a unique style of tonsure.[19] The Synod of Whitby in 664, however, ended these distinctives as it ruled "that Easter would be celebrated according to the Roman date, not the Celtic date."[20] Although Roman influence came to dominate the Church in Scotland,[20] certain Celtic influences remained in the Scottish Church,[21] such as "the singing of metrical psalms, many of them set to old Celtic Christianity Scottish traditional and folk tunes", which later became a "distinctive part of Scottish Presbyterian worship".[22][23]

While the Church of Scotland traces its roots back to the earliest Christians in Scotland, its identity was principally shaped by the Scottish Reformation of 1560. At that point, many in the then church in Scotland broke with Rome, in a process of Protestant reform led, among others, by John Knox. It reformed its doctrines and government, drawing on the principles of John Calvin which Knox had been exposed to while living in Geneva, Switzerland. In 1560, an assembly of some nobles, lairds and burgesses, as well as several churchmen, claiming in defiance of the Queen to be a Scottish Parliament, abolished papal jurisdiction and approved the Scots Confession, but did not accept many of the principles laid out in Knox's First Book of Discipline, which argued, among other things, that all of the assets of the old church should pass to the new. The 1560 Reformation Settlement was not ratified by the crown, as Mary I, a Catholic, refused to do so, and the question of church government also remained unresolved. In 1572 the acts of 1560 were finally approved by the young James VI, but the Concordat of Leith also allowed the crown to appoint bishops with the church's approval. John Knox himself had no clear views on the office of bishop, preferring to see them renamed as 'superintendents' which is a translation of the Greek; but in response to the new Concordat a Presbyterian party emerged headed by Andrew Melville, the author of the Second Book of Discipline.

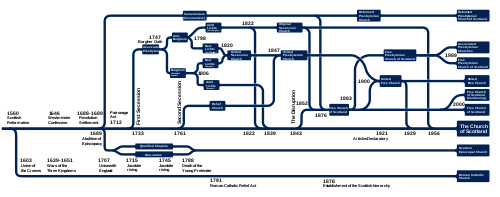

Melville and his supporters enjoyed some temporary successes—most notably in the Golden Act of 1592, which gave parliamentary approval to Presbyterian courts. James VI, who succeeded to the English throne in 1603, believed that Presbyterianism was incompatible with monarchy, declaring "No bishop, no king"[24] and by skillful manipulation of both church and state, steadily reintroduced parliamentary and then diocesan episcopacy. By the time he died in 1625, the Church of Scotland had a full panel of bishops and archbishops. General Assemblies met only at times and places approved by the Crown.

Charles I inherited a settlement in Scotland based on a balanced compromise between Calvinist doctrine and episcopal practice. Lacking the political judgement of his father, he began to upset this by moving into more dangerous areas. Disapproving of the 'plainness' of the Scottish service he, together with his Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, sought to introduce the kind of liturgical practice in use in England. The centrepiece of this new strategy was the Prayer Book of 1637, a slightly modified version of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. Although this was devised by a panel of Scottish bishops, Charles' insistence that it be drawn up in secret and adopted sight-unseen led to widespread discontent. When the Prayer Book was finally introduced at St Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh in mid-1637 it caused an outbreak of rioting, which, starting with Jenny Geddes, spread across Scotland. In early 1638 the National Covenant was signed by large numbers of Scots, protesting at the introduction of the Prayer Book and other liturgical innovations that had not first been tested and approved by free Parliaments and General Assemblies of the Church. In November 1638, the General Assembly in Glasgow, the first to meet for twenty years, not only declared the Prayer Book unlawful, but went on to abolish the office of bishop itself. The Church of Scotland was then established on a Presbyterian basis. Charles' attempt at resistance to these developments led to the outbreak of the Bishops' Wars. In the ensuing civil wars, the Scots Covenanters at one point made common cause with the English parliamentarians—resulting in the Westminster Confession of Faith being agreed by both. This document remains the subordinate standard of the Church of Scotland, but was replaced in England after the Restoration. O

Episcopacy was reintroduced to Scotland after the Restoration, the cause of considerable discontent, especially in the south-west of the country, where the Presbyterian tradition was strongest. The modern situation largely dates from 1690, when after the Glorious Revolution the majority of Scottish bishops were non-jurors, that is, they believed they could not swear allegiance to William II and Mary II while James VII lived. To reduce their influence the Scots Parliament guaranteed Presbyterian governance of the Church by law, excluding what became the Scottish Episcopal Church. Most of the remaining Covenanters, disagreeing with the Restoration Settlement on various political and theological grounds, most notably because the Settlement did not acknowledge the National Covenant and Solemn League and Covenant, also did not join the Church of Scotland, instead forming the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Scotland in 1690.

Controversy still surrounded the relationship between the Church of Scotland's independence and the civil law of Scotland. The interference of civil courts with Church decisions, particularly over the appointment of ministers, following the Church Patronage (Scotland) Act 1711, which gave landowners, or patrons, the right to appoint ministers to vacant pulpits, would lead to several splits. This began with the secession of 1733 and culminated in the Disruption of 1843, when a large portion of the Church broke away to form the Free Church of Scotland. The seceding groups tended to divide and reunite among themselves—leading to a proliferation of Presbyterian denominations in Scotland.

The British Parliament passed the Church of Scotland Act 1921, finally recognising the full independence of the Church in matters spiritual, and as a result of this, and passage of the Church of Scotland (Property and Endowments) Act 1925, the Kirk was able to unite with the United Free Church of Scotland in 1929. The United Free Church of Scotland was itself the product of the union of the former United Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the majority of the Free Church of Scotland in 1900.

Some independent Scottish Presbyterian denominations still remain. These include the Free Church of Scotland—sometimes given the epithet The Wee Frees—(originally formed of those congregations which refused to unite with the United Presbyterian Church in 1900), the United Free Church of Scotland (formed of congregations which refused to unite with the Church of Scotland in 1929), the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland (which broke from the Free Church of Scotland in 1893), the Associated Presbyterian Churches (which emerged as a result of a split in the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland in the 1980s) and the Free Church of Scotland (Continuing) (which emerged from a split in the Free Church of Scotland in 2000).

The motto of the Church of Scotland is nec tamen consumebatur (Latin)—"Yet it was not consumed", an allusion to Exodus 3:2 and the Burning Bush.

Theology and practice

The basis of faith for the Church of Scotland is the Word of God, which it views as being "contained in the Scriptures of the Old and New Testament". Its principal subordinate standard is The Westminster Confession of Faith (1647), although here liberty of opinion is granted on those matters "which do not enter into the substance of the faith" (Art. 2 and 5). (The 19th century Scottish distinction was between 'evangelicals' and 'moderates'.) There is no official document in which substantial matters and insubstantial ones are clearly demarcated.

The Church of Scotland has no compulsory prayer book, although it does have a hymn book (the 4th edition was published in 2005). Its Book of Common Order contains recommendations for public worship, which are usually followed fairly closely in the case of sacraments and ordinances. Preaching is the central focus of most services. Traditionally, Scots worship centred on the singing of metrical psalms and paraphrases, but for generations these have been supplemented with Christian music of all types.[22] The typical Church of Scotland service lasts about an hour. There is normally no sung or responsive liturgy, but worship is the responsibility of the minister in each parish, and the style of worship can vary and be quite experimental. In recent years, a variety of modern song books have been widely used to appeal more to contemporary trends in music, and elements from alternative liturgies including those of the Iona Community are incorporated in some congregations. Although traditionally worship is conducted by the parish minister, participation and leadership by members who are not ministers in services is becoming more frequent, especially in the Highlands and the Borders.

In common with other Reformed denominations, the Church recognises two sacraments: Baptism and Holy Communion (the Lord's Supper). The Church baptises both believing adults and the children of Christian families. Communion in the Church of Scotland today is open to Christians of whatever denomination, without precondition. Communion services are usually taken fairly seriously in the Church; traditionally, a congregation held only three or four per year, although practice now greatly varies between congregations. In some congregations, communion is celebrated once a month.

Theologically, the Church of Scotland is Reformed (ultimately in the Calvinist tradition) and is a member of the World Alliance of Reformed Churches.[6]

Ecumenical relations

The Church of Scotland is a member of ACTS (Action of Churches Together in Scotland) and, through its Committee on Ecumenical Relations, works closely with other denominations in Scotland. The present inter-denominational co-operation marks a distinct change from attitudes in certain quarters of the Church in the early twentieth century and before, when opposition to Irish Roman Catholic immigration was vocal (see Catholicism in Scotland). The Church of Scotland is a member of the World Council of Churches, the Conference of European Churches, the Community of Protestant Churches in Europe, and the World Communion of Reformed Churches. The Church of Scotland is a member of Churches Together in Britain and Ireland and, through its Presbytery of England, is a member of Churches Together in England. The Church of Scotland continues to foster relationships with other Presbyterian denominations in Scotland even where agreement is difficult. In May 2016 the Church of Scotland ratified the Columba Agreement (approved by the Church of England's General Synod in February 2016), calling for the two churches to work more closely together on matters of common interest.

"God's Invitation"

While the Bible is the basis of faith of the Church of Scotland, and the Westminster Confession of Faith is the subordinate standard,[25][26] a request was presented to a General Assembly of the Church of Scotland for a statement explaining the historic Christian faith in jargon-free non-theological language. "God's Invitation" was prepared to fulfil that request. The full statement reads:[27]

God made the world and all its creatures with men and women made in His image.

By breaking His laws people have broken contact with God, and damaged His good world. This we see and sense in the world and in ourselves.

The Bible tells us the Good News that God still loves us and has shown His love uniquely in His Son, Jesus Christ. He lived among us and died on the cross to save us from our sin. But God raised Him from the dead!

In His love, this living Jesus invites us to turn from our sins and enter by faith into a restored relationship with God Who gives true life before and beyond death.

Then, with the power of the Holy Spirit remaking us like Jesus, we—with all Christians—worship God, enjoy His friendship and are available for Him to use in sharing and showing His love, justice, and peace locally and globally until Jesus returns!

In Jesus' name we gladly share with you God's message for all people—You matter to God!

It was approved for use by the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in May 1992.[28]

Current issues

Decline

The Church of Scotland faces many current difficulties. Between 1966 and 2006, the number of members fell from over 1,230,000 to 504,000,[29] reducing further to 446,000 in 2010 [30] and 352,912 by yearend 2015.[7] The Scottish Church Census reported that only around 137,000 people worship on an average Sunday in a Church of Scotland, approximately 41% of the stated membership. On current rates of decline, the Church of Scotland has less than 25 years of existence left.

In April 2016 the Scottish Social Attitudes survey showed just 20% claiming to belong to the Church of Scotland; down from 35% in 1999.[31] The church faces a £5.7 million deficit, and the costly upkeep of many older ecclesiastical buildings. In response the church has decided to 'prune to grow', reducing ministry provision plans from 1,234 to 1,000 funded posts (1,075 established FTE posts, of which 75 will be vacant at any one time) supported by a variety of voluntary and part-time ministries. At the same time the number of candidates accepted for full-time ministry has reduced from 24 (2005) to 8 (2009).[32] Since 2014, the number of full-time candidates accepted into training each year has been in the range of 13 to 16. At the 2016 General Assembly the Moderator pointed to issues such as: 25% of charges without a minister; all but two ministers over the age of 30; falling clergy numbers over the coming six years (anticipated that for each newly recruited minister there will be four retirements).[33]

This lack of those in training towards ministry has threatened the viability of the Kirk's theological training colleges.[34] During the 2019 General Assembly, the Ministries Council announced that they were looking to reduce the number of Academic Partners who train current ministry students from five, to either one or two. The five current academic partners are University of Glasgow, University of Edinburgh, University of Aberdeen, University of St Andrews and, most recently, Highland Theological College.

In 2018, the Ministries Council predicted, that on current trends, the Church of Scotland would have only 611 Full-Time Equivalent Ministers in post due to the age profile of the ministry, and the shortfall in new candidates, down from the 775 in post at that time. This would result in some Presbyteries likely to have less than half of their positions filled.

Women's ordination

Since 1968, all ministries and offices in the church have been open to women and men on an equal basis. In 2004, Alison Elliot was chosen to be Moderator of the General Assembly, the first woman in the post and the first non-minister to be chosen since George Buchanan, four centuries before. In May 2007 the Rev Sheilagh M. Kesting became the first female minister to be Moderator. There are currently 218 serving female ministers, with 677 male ministers.

Human sexuality

There is a division in the Church of Scotland on how the issues surrounding LGBT sexuality should be addressed. Currently, the Kirk allows pastors to enter into same-sex marriages and civil partnerships while also defining marriage as between a man and a woman.[35] This division of approach is illustrated by opposition to an attempt to install as minister an openly homosexual man who intends to live with his partner once appointed to his post.[36] In a landmark decision, the General Assembly (GA) voted on 23 May 2009 by 326 to 267 to ratify the appointment of the Reverend Scott Rennie, the Kirk's first out, non-celibate gay minister. The decision was reached on the basis the presbytery had followed the correct procedure. Rennie had won the overwhelming support of his prospective church members at Queen's Cross, Aberdeen, but his appointment was in some doubt until extensive debate and this vote by the commissioners to the assembly. The GA later agreed upon a moratorium on the appointment of further non-celibate gay people until after a special commission has reported on the matter.[37] (See: LGBT clergy in Christianity)

As a result of these developments, a new grouping of congregations within the church was begun "to declare their clear commitment to historic Christian orthodoxy", known as the Fellowship of Confessing Churches.[38] In May 2011, the GA of the Church of Scotland voted to appoint a theological commission, with a view to fully investigating the matter, reporting to the General Assembly of 2013. Meanwhile, openly homosexual ministers ordained before 2009 would be allowed to keep their posts without fear of sanction.[39] On 20 May 2013, the GA voted in favour of a proposal that allows liberal parishes to opt out of the church's policy on homosexuality.[40] It was reported that seceding congregations had a combined annual income of £1 million.[41] Since 2008, 25 out of 808 (3%) ministers had left over the issue.[42]

The church opposed proposals for blessing of same-sex marriage, stating that "The government's proposal fundamentally changes marriage as it is understood in our country and our culture – that it is a relationship between one man and one woman."[43] However, in 2015, the Church of Scotland's GA voted in favour of recommending that gay ministers be able to enter into same-sex marriages.[44][45] Also in 2015, the GA voted in favour of allowing pastors to enter in same-sex civil partnerships.[46] On 21 May 2016, the GA voted in favour of the approval for gay and lesbian ministers to enter into same-sex marriages.[47] In 2017, it was announced that there is a "report to be debated at the Kirk's General Assembly in May [that] proposes having a church committee research allowing nominated ministers and deacons to carry out the ceremonies, but wants to retain the ability for 'contentious refusal' from those opposed to same-sex marriage."[48] Regarding transgender people, many congregations and clergy within the denomination affirm the full inclusion of transgender and other LGBTI people within the church through Affirmation Scotland.[49][50] A Theological Forum report calling for the approval of same-sex marriage and an apology to homosexuals for past mistreatment was approved by the General Assembly on 25 May 2017.[51] "But despite strong support in the church’s governing body, it is likely to be several years before the first same-sex marriage is conducted by a Kirk minister. The necessary legal changes will first be brought to [the 2018] year’s assembly."[52]

In 2018, the Kirk's assembly voted in favour of drafting a new church law to allow same-sex marriages.[53] The new laws would give ministers the option of performing same-sex marriages and the Kirk is expected to vote on a final poll in 2021.[54]

"The Inheritance of Abraham: A Report on the 'Promised' Land"

In April 2013, the church published a report entitled "The Inheritance of Abraham: A Report on the 'Promised' Land" which included a discussion of Israeli and Jewish claims to the Land of Israel. The report said "there has been a widespread assumption by many Christians as well as many Jewish people that the Bible supports an essentially Jewish state of Israel. This raises an increasing number of difficulties and current Israeli policies regarding the Palestinians have sharpened this questioning", and that "promises about the Land of Israel were never intended to be taken literally". The church responded to criticism by saying that "The Church has never and is not now denying Israel's right to exist; on the contrary, it is questioning the policies that continue to keep peace a dream in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory. This report is against the injustices levelled against the Palestinian people and how land is shared. It is also a reflection of the use or misuse of scripture to claim divine right to land by any group" and says it must "refute claims that scripture offers any peoples a privileged claim for possession of a particular territory".[55]

The Scottish Council of Jewish Communities sharply criticised the report,[56] describing it as follows: "It reads like an Inquisition-era polemic against Jews and Judaism. It is biased, weak on sources, and contradictory. The picture it paints of both Judaism and Israel is barely even a caricature. The arrogance of telling the Jewish people how to interpret Jewish texts and Jewish theology is breathtaking."[57] The report was also criticised by the Anti-Defamation League and the Israeli envoy to the United Kingdom.[58][59][60][61][62]

Reverend Sally Foster-Fulton, who served as the Convener of the Church and Society Council, defended the report, stating that: "This is primarily a report highlighting the continued occupation by the state of Israel and the injustices faced by the Palestinian people as a consequence. It is not a report criticising the Jewish people. Opposing the unjust policies of the state of Israel cannot be equated to anti-Semitism." In an interview with Iran's Press TV, Reverend Stephen Sizer expressed support for the document, stating that "it's news that the Israelis don't want because they want to maintain the idea that they have the Church in their pocket."[63]

Dennis Prager criticized the church, writing that the document was "profoundly anti-Semitic" and "an act of theological forgery; it makes a mockery of the Bible as a coherent document and it renders Christianity inherently anti-Semitic" by "invalidating the Jewish people and invalidating the Jews' historically incontestable claims to the land upon which the only independent states that ever existed were Jewish".[64]

In response to criticism, the church quickly replaced the original version with a modified one, stating that criticism of Israel's policies toward the Palestinians "should not be misunderstood as questioning the right of the State of Israel to exist".[65]

Life Issues

The Church of Scotland is generally anti-abortion, stating that it should be allowed "only on grounds that the continuance of the pregnancy would involve serious risk to the life or grave injury to the health, whether physical or mental, of the pregnant woman."[66]

The Church of Scotland also opposes euthanasia: "The General Assembly has consistently stated that: 'the Christian recognises no right to dispose of his own life even although he may regard those who commit or may attempt to commit suicide with compassion and understanding rather than condemnation'. The Church has frequently stressed its opposition to various attempts to introduce legislation to permit euthanasia, even under strictly controlled circumstances as incompatible with Christianity." The church is associated with the Care Not Killing organisation in "Promoting more and better palliative care./ Ensuring that existing laws against euthanasia and assisted suicide are not weakened or repealed during the lifetime of the current Parliament./ Influencing the balance of public opinion further against any weakening of the law."[67]

Historically, the Church of Scotland supported the death penalty; the General Assembly once called for the "vigorous execution" of Thomas Aikenhead, who was found guilty of blasphemy in 1696.[68] Nowadays, the Kirk strongly disapproves of the death penalty: "The Church of Scotland affirms that capital punishment is always and wholly unacceptable and does not provide an answer even to the most heinous of crimes. It commits itself to working with other churches and agencies to advance this understanding, oppose death sentences and executions and promote the cause of abolition of the death penalty worldwide."[69]

The Church of Scotland does not consider marriage to be a sacrament, and thus not binding forever, and has no moral objection to the remarriage of divorced persons. The minister who is asked to perform a ceremony for someone who has a prior spouse living may inquire for the purpose of ensuring that the problems which led to the divorce do not recur.[70]

Position in Scottish society

| Religion | Percentage of population |

|---|---|

| No religion | 36.7% |

| Church of Scotland | 32.4% |

| Roman Catholic | 15.9% |

| No answer | 7.0% |

| Other Christian | 5.5% |

| Islam | 1.4% |

| Hinduism | 0.3% |

| Other religions | 0.3% |

| Buddhism | 0.2% |

| Sikhism | 0.2% |

| Judaism | 0.1% |

At the time of the 2001 census, the number of respondents who gave their religion as Church of Scotland was 2,146,251 which amounted to 42.4% of the population of Scotland.[71] In 2008 the Church of Scotland had around 995 active ministers, 1,118 congregations, and its official membership at 398,389 comprised about 7.5% of the population of Scotland. Official membership is down some 66.5% from its peak in 1957 of 1.32 million.[72] In the 2011 national census, 32% of Scots identified their religion as "Church of Scotland", more than any other faith group, but falling behind the total of those without religion for the first time.[71] However, by 2013 only 18% of Scots self-identified as Church of Scotland.[73] The Church of Scotland Guild, the Kirk's historical women's movement and open to men and women since 1997, is still the largest voluntary organisation in Scotland.

Along ethnic or racial lines, the Church of Scotland was in historic times, and has remained at present, overwhelmingly white or light-skinned in membership, as have been other branches of Scottish Christianity. According to the 2011 census, among respondents who identified with the Kirk, 96% are white Scots, 3% are other white people, and 1% is either ethnically mixed; Asian, Asian Scottish or Asian British; African; Caribbean or black; or from other ethnic groups.[74]

Although it is the national church,[75] the Kirk is not a state church;[76][77] this and other regards makes it dissimilar to the Church of England (the established church in England).[75] Under its constitution (recognised by the 1921 act of the British Parliament), the Kirk enjoys complete independence from the state in spiritual matters.[75] When in Scotland, the British monarch simply attends church, as opposed to her role in the English Church as Supreme Governor.[75] The monarch's accession oath includes a promise to "maintain and preserve the Protestant Religion and Presbyterian Church Government".[75] She is formally represented at the annual General Assembly by a Lord High Commissioner[78] unless she chooses to attend in person; the role is purely formal, and the monarch has no right to take part in deliberations.[75]

The Kirk is committed to its 'distinctive call and duty to bring the ordinances of religion to the people in every parish of Scotland through a territorial ministry' (Article 3 of its Articles Declaratory). This means the Kirk in practice maintains a presence in every community in Scotland. The Kirk also pools its resources to ensure continuation of this presence.

The Kirk played a leading role in providing universal education in Scotland (the first such provision in the modern world), largely due to its teaching that all should be able to read the Bible. Today it does not operate schools, as these were transferred to the state in the latter half of the 19th century.

Governance and administration

The Church of Scotland is Presbyterian in polity and Reformed in theology. The most recent articulation of its legal position, the Articles Declaratory (1921), spells out the key concepts.

Courts and assemblies

As a Presbyterian church, the Kirk has no bishops but is rather governed by elders and ministers (collectively called presbyters) sitting in a series of courts. Each congregation is led by a Kirk Session. The Kirk Sessions in turn are answerable to regional presbyteries (of which the Kirk currently has over 40). The supreme body is the annual General Assembly, which meets each May in Edinburgh.

Moderator

Each court is convened by the 'moderator'—at the local level of the Kirk Session normally the parish minister who is ex officio member and Moderator of the Session. Congregations where there is no minister, or where the minister is incapacitated may be moderated by a specially trained elder. Presbyteries and the General Assembly elect a moderator each year. The Moderator of the General Assembly serves for the year as the public representative of the Church, but beyond that enjoys no special powers or privileges and is in no sense the leader or official spokesperson of the Kirk. At all levels, moderators may be either elders or ministers. Only Moderators of Kirk Sessions are obliged to be trained for the role.

Councils

At a national level, the work of the Church of Scotland is chiefly carried out by "Councils", each supported by full-time staff mostly based at the Church of Scotland Offices in Edinburgh. The Councils are:

- Council of Assembly

- Church and Society Council

- Ministries Council

- Mission and Discipleship Council

- Social Care Council (based at Charis House, Edinburgh)

- World Mission Council

The Church of Scotland's Social Care Council (known as CrossReach) is the largest provider of social care in Scotland today, running projects for various disadvantaged and vulnerable groups: including care for the elderly; help with alcoholism, drug, and mental health problems; and assistance for the homeless.

The national Church has never shied from involvement in Scottish politics. In 1919, the General Assembly created a Church and Nation Committee, which in 2005 became the Church and Society Council. The Church of Scotland was (and is) a firm opponent of nuclear weaponry. Supporting devolution, it was one of the parties involved in the Scottish Constitutional Convention, which resulted in the setting up of the Scottish Parliament in 1997. Indeed, from 1999–2004 the Parliament met in the Kirk's Assembly Hall in Edinburgh, while its own building was being constructed. The Church of Scotland actively supports the work of the Scottish Churches Parliamentary Office in Edinburgh.

Other Church agencies include:

- Assembly Arrangements Committee

- Committee on Chaplains to HM Forces

- Church of Scotland Guild

- Committee on Church Art and Architecture (part of the Mission and Discipleship Council)

- Ecumenical Relations Committee

- Stewardship and Finance Department

- General Trustees (responsible for church buildings)

- Legal Questions Committee

- Panel on Review and Reform

- Department of the General Assembly

- Safeguarding Service (protection of children and vulnerable adults)

Church offices

The Church of Scotland Offices are located at 121 George Street, Edinburgh. These imposing buildings—popularly known in Church circles as "one-two-one"—were designed in a Scandinavian-influenced style by the architect Sydney Mitchell and built in 1909–1911 for the United Free Church of Scotland. Following the union of the churches in 1929 a matching extension was built in the 1930s.

The offices of the Moderator, Principal Clerk, General Treasurer, Law Department and all the Church councils are located at 121 George Street, with the exception of the Social Care Council (CrossReach). The Principal Clerk to the General Assembly is the Rev Dr George Whyte. Each Council has its own Council Secretary who sit as a senior management team led by the Secretary to the Council of Assembly, currently the Rev Dr Martin Scott.

Publications

The following publications are useful sources of information about the Church of Scotland.

- Life and Work – the monthly magazine of the Church of Scotland.

- Church of Scotland Yearbook (known as "the red book") – published annually with statistical data on every parish and contact information for every minister.

- Reports to the General Assembly (known as "the blue book") – published annually with reports on the work of the church's departments.

- The Constitution and Laws of the Church of Scotland (known as "the green book") edited by the Very Rev Dr James L. Weatherhead, published 1997 by the Church of Scotland, ISBN 0-86153-246-5 and which has now replaced the venerable

- Practice and Procedure in The Church of Scotland edited by Rev. James Taylor Cox, D.D. published by The Committee on General Administration, The Church of Scotland, 1976 (sixth edition) ISBN 0-7152-0326-6

- Fasti Ecclesiae Scoticanae – published irregularly since 1866, contains biographies of ministers.

- The First and Second Books of Discipline of 1560 and 1578.

- The Book of Common Order latest version of 1994.

See also

- History and concepts

- Ministry and congregations

- Organisation

- List of Presbyteries and (former) Synods

- Ministers and elders in the Church of Scotland

- Moderators and clerks in the Church of Scotland

- Issues

- Bodies to which the Church of Scotland is affiliated

- Other bodies

- Legislation

- Commercial Interests

References

- Nimmo, Paul T.; Fergusson, David A. S. (26 May 2016). The Cambridge Companion to Reformed Theology. Cambridge University Press. p. 248. ISBN 9781107027220.

The established and national Church of Scotland was Reformed and Presbyterian, and dominated the Divinity Faculties of the ancient universities.

- Church of Scotland May 2019

- "Queen and the Church". royal.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- "Articles Declaratory of the Constitution of the Church of Scotland". The Church of Scotland. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

The principal subordinate standard of the Church of Scotland is the Westminster Confession of Faith approved by the General Assembly of 1647, containing the sum and substance of the Faith of the Reformed Church. Its government is Presbyterian, and is exercised through Kirk Sessions; Presbyteries, [Provincial Synods deleted by Act V, 1992], and General Assemblies. Its system and principles of worship, orders, and discipline are in accordance with "The Directory for the Public Worship of God," "The Form of Presbyterial Church Government " and "The Form of Process," as these have been or may hereafter be interpreted or modified by Acts of the General Assembly or by consuetude.

- "Joining the Church". Church of Scotland. 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

The usual pattern for joining the Church of Scotland is that infant children of Church members are received into the Church through Baptism. In time it is hoped that the child will come to make his or her own public profession of faith and the congregation will support the family in this task. This public profession of faith is sometimes referred to as confirmation.

- "Members". World Communion of Reformed Churches. 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- "Church of Scotland 'struggling to stay alive'". scotsman.com.

- BST, Harry Farley Mon 21 May 2018 12:22. "Membership decline means Church of Scotland's 'very existence' under threat, report warns". www.christiantoday.com.

- COUNCIL OF ASSEMBLY MAY 2019

- "Scotland's People Annual Report 2018" (PDF). Scottish Government. September 2019.

- Atkins, Gareth (1 August 2016). Making and Remaking Saints in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Manchester University Press. p. 104. ISBN 9781526100238.

For many Presbyterian evangelicals in Scotland, the 'achievements of the Reformation represented the return to a native or national tradition, the rejection of an alien tyranny that had suppressed ... Scotland's true character as a Presbyterian nation enjoying the benefits of civil and religious liberty'. What they had in mind was the mission established by Columba at Iona and the subsequent spread of Christianity through the Culdees of the seventh to eleventh centuries. For Presbyterian scholars in the nineteenth century, these communities of clergy who differed in organisation and ethos from later monastic orders were further evidence of the similarity between early Christianity in Ireland and Scotland and later Presbyterianism. This interpretation of the character of the Celtic Church was an important aspect of Presbyterian identity in global terms. At the first meeting in 1877 of the Alliance of the Reformed Churches holding the Presbyterian System (later the World Alliance of Reformed Churches), Peter Lorimer (1812-79), a Presbyterian professor in London, noted 'that the early Church of St. Patrick, Columba, and Columbanus, was far more nearly allied in its fundamental principles of order and discipline to the Presbyterian than to the Episcopalian Churches of modern times'.

- Taylor, James; Anderson, John (1852). The Pictorial History of Scotland. p. 51.

The zealous Presbyterian maintains, that the church established by Columba was formed on a Presbyterian model, and that it recognized the great principle of clerical equality.

- Bradley, Ian (24 July 2013). Columba. Wild Goose Publications. p. 29. ISBN 9781849522724.

Columba has found favour with enthusiasts for all things Celtic and with those who have seen him as establishing a proto-Presbyterian church clearly distinguishable from the episcopally goverened church favoured by Rome-educated Bishop Ninian.

- Dickens-Lewis, W.F. (1920). "Apostolicity of Presbyterianism: Ancient Culdeeism and Modern Presbyterianism". The Presbyterian Magazine. Presbyterian Church (USA). 26 (1–7): 529.

The Culdees who claimed at the Synod of Whitby apostolic descent from St. John, as against the Romish claim of the authority of St. Peter, retired into Scotland.

- Thomson, Thomas (1896). A History of the Scottish People from the Earliest Times. Blackie. p. 141.

...for the primitive apostolic church which St. John had established in the East and Columba transported to our shores. Thus the days of Culdeeism were numbered, and she was now awaiting the martyrs doom.

- Mackay, John; Mackay, Annie Maclean Sharp (1902). The Celtic Monthly. Archibald Sinclair. p. 236.

- Hannrachain, T. O'; Armstrong, R.; hAnnracháin, Tadhg Ó (30 July 2014). Christianities in the Early Modern Celtic World. Springer. p. 198. ISBN 9781137306357.

Presbyterians after 1690 gave yet more play to 'Culdeeism', a reading of the past wherein 'culdees' (derived from céli dé) were presented as upholding a native, collegiate, proto-presbyterian church government uncontaminated by bishops.

- Rankin, James (1884). The Young Churchman: lessons on the Creed, the Commandments, the means of grace, and the Church. William Blackwood and Sons. p. 84.

For seven whole centuries (AD 400-1100) there existed in Scotland a genuine Celtic Church, apparently of Greek origin, and in close connection with both Ireland and Wales. In this Celtic Church no Pope was recognized, and no prelatical of diocesan bishops existed. Their bishops were of the primitive New Testament style--presbyter-bishops. Easter was kept at a different time from that of Rome. The tonsure of the monks was not, like that of Rome, on the crown, but across the forehead from ear to ear. The monastic system of the Celtic Church was extremely simple--small communities of twelve men were presided over by an abbot (kindred to the Patriarch title of the Greeks), who took precedence of the humble parochial bishops.

- Sawyers, June Skinner (1999). Maverick Guide to Scotland. Pelican Publishing. p. 57. ISBN 9781455608669.

The Celtic Church evolved separated from the Roman Catholic Church. The Celtic Church was primarily monastic, and the monasteries were administered by an abbot. Not as organized as the church in Rome, it was a much looser institution. The Celtic Church celebrated Easter on a different date from the Roman, too. Life within the Celtic Church tended to be ascetic. Education was an important element, as was passion for spreading the word, that is, evangelism. The Celtic brothers led a simple life in simply constructed buildings. The churches and monastic buildings were usually made of wood and wattle and had thatched roofs. After the death of St. Columba in AD 597, the autonomy of the Celtic Church did not last long. The Synod of Whitby in 664 decided, once and for all, that Easter would be celebrated according to the Roman date, not the Celtic date. This was the beginning of the end for the Celtic Church.

- Eggins, Brian (2 March 2015). History & Hope: The Alliance Party in Northern Ireland. History Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780750964753.

After the Synod of Whitby in about 664, the Roman tradition was imposed on the whole Church, though remnants of the Celtic tradition lingered in practice.

- Bowden, John Stephen (2005). Encyclopedia of Christianity. Oxford University Press. p. 242. ISBN 9780195223934.

A distinctive part of Scottish Presbyterian worship is the singing of metrical psalms, many of them set to old Celtic Christianity Scottish traditional and folk tunes. These verse psalms have been exported to Africa, North America and other parts of the world where Presbyterian Scots missionaries or Emigres have been influential.

- Hechter, Michael (1995). Internal Colonialism: The Celtic Fringe in British National Development. Transaction Publishers. p. 168. ISBN 9781412826457.

Last, because Scotland was a sovereign land in the sixteenth century, the Scottish Reformation came under the influence of John Knox rather than Henry Tudor. The organization of the Church of Scotland became Presbyterian, with significant Calvinist influences, rather than Episcopalian. Upon incorporation Scotland was allowed to keep her church intact. These regional religious differences were to an extent superimposed upon linguistic differences in Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. One of the legacies of the Celtic social organization was the persistence of the Celtic languages Gaelic and Welsh among certain groups in the periphery.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Ordinal and Service Book, Open University Press 1931

- Westminster Confession of Faith Archived 22 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine page at Church of Scotland website

- "God's Invitation". Parish Church of Dull and Weem. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011.

- Reports to the General Assembly 1992, Church of Scotland, Edinburgh 1992

- Church of Scotland 2007–2008 Year Book, p. 350

- "church of scotland statistics 1999 - 2010" (PDF).

- "Most people in Scotland 'not religious'". 3 April 2016 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 February 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Kirk's College of Divinity has so few students it is 'scarcely viable'". Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- Scotland, The Church of (24 April 2017). "General Assembly allows ministers and deacons in same-sex marriages". www.churchofscotland.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2 May 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- "BBC - Will & Testament: Presbyterians prepare for a theological battle". bbc.co.uk.

- Church backs first openly gay minister – Herald Scotland Archived 27 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Member Churches Archived 7 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine confessingchurch.org.uk, accessed 7 July 2009

- Severin Carrell. "Church of Scotland votes to allow gay and lesbian ministers". the Guardian.

- "Church of Scotland General Assembly votes to allow gay ministers". BBC News.

- "Kirk could lose £1m a year over gay ordination". Herald Scotland.

- Gledhill, Ruth (21 May 2016). "Church of Scotland votes in favour of ministers in gay marriages". Christian Today. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Church of Scotland against gay marriage law change". bbc.co.uk. BBC News. 1 December 2011. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2013..

- Carrell, Severin (21 May 2015). "Church of Scotland opens door for appointment of married gay ministers". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- "Church of Scotland decision on married gay clergy delayed". www.yahoo.com. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Church of Scotland votes to allow gay ministers in civil partnerships". BBC News. 16 May 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- Association, Press (21 May 2016). "Church of Scotland votes to allow ministers to be in same-sex marriages". the Guardian. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Church of Scotland to debate allowing same-sex marriages - BelfastTelegraph.co.uk". BelfastTelegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- "Affirmation Scotland – seeking to create a more inclusive church". KaleidoScot. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- Church, Queen's Cross. "Affirmation! Scotland · Our Partners · Queen's Cross Church". www.queenscrosschurch.org.uk. Archived from the original on 9 June 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- "Kirk moves towards allowing gay marriage". 25 May 2017 – via www.bbc.com.

- Sherwood, Harriet (25 May 2017). "Church of Scotland in step towards conducting same-sex marriages". the Guardian.

- "Kirk moves closer to gay marriage services". BBC News. 19 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- "Church of Scotland to draft new same-sex marriage laws". the Guardian. Press Association. 19 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- "Israel condemns contentious Church of Scotland report". ynet.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 15 December 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) SCoJeC Rebukes Church of Scotland over General Assembly Report

- Scottish Church denial of Jewish land rights stirs ire Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine by Jewish Telegraphic Agency, (reprinted in the Jerusalem Post), 5 May 2013.

- "Church of Scotland to alter report denying Jews' claims to Israel". Haaretz. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 12 May 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- Atheist Stephen Hawking and Church of Scotland both determined to demonize Israel Archived 28 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine by Rabbi Abraham Cooper, Fox News, 9 May 2013.

- Scottish Church to debate Jewish right to land of Israel Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine by Marcus Dysch, The Jewish Chronicle, 2 May 2013.

- Church of Scotland Insults Jews With Denial of Claim to Israel Archived 20 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine by Liam Hoare, The Jewish Daily Forward, 10 May 2013.

- Church of Scotland: Jews do not have a right to the land of Israel Archived 15 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine by Anshel Pfeffer, Haaretz, May 3, 2013.

- New report questions Israel's claim of "divine right" Archived 8 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Press TV, May 7, 2013.

- "The Church of Scotland's Scandal" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine by Dennis Prager, Townhall.com, May 14, 2013.

- "Church of Scotland Thinks Twice, Grants Israel the Right to Exist" Archived 28 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The Jewish Press, 12 May 2013.

- "Apologetics - Sanctity of Life - Abortion". christian.org.uk. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011.

- "End of life issues". churchofscotland.org.uk.

- Andrew Hill Thomas Aikenhead Archived 1 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography monograph at website of Unitarian Universalist Association, c.1999

- "Criminal justice". churchofscotland.org.uk.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Analysis of Religion in the 2001 Census". The Scottish Government. 17 May 2006. Archived from the original on 23 December 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- 'Kirk failing in its moral obligation to parishioners Archived 17 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine' The Herald 12 May 2008

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Scotland's Census 2011. "Table LC2201SC - Ethnic group by religion" (Spreadsheet). National Records of Scotland. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "How we are organised. The Kirk and the State". Church of Scotland website. Church of Scotland. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- "Church of Scotland". 17 February 2011.

- Brady, Thomas A.; Oberman, Heiko Augustinus; Tracy, James D. (14 March 1994). Handbook of European History 1400 - 1600: Late Middle Ages, Renaissance and Reformation. BRILL. ISBN 9004097627 – via Google Books.

- "Page 3033 | Issue 27310, 3 May 1901 | London Gazette | The Gazette".

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Church of Scotland. |

- Official Church of Scotland website

- 'Church without Walls' report

- website of Action of Churches Together in Scotland

- Church of Scotland daily news monitor and links at Scottish Christian.com

- "Neuroscience and the Church of Scotland". Research Impact - Humanities and Social Science: making a difference. College of Humanities and Social Science, The University of Edinburgh. 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

The Church of Scotland invited a philosopher from the University of Edinburgh to explore scientific challenges to free will and moral responsibility.