Pollution

Pollution is the introduction of contaminants into the natural environment that cause adverse change.[1] Pollution can take the form of chemical substances or energy, such as noise, heat or light. Pollutants, the components of pollution, can be either foreign substances/energies or naturally occurring contaminants. Pollution is often classed as point source or nonpoint source pollution. In 2015, pollution killed 9 million people in the world.[2][3]

Major forms of pollution include: Air pollution, light pollution, littering, noise pollution, plastic pollution, soil contamination, radioactive contamination, thermal pollution, visual pollution, water pollution.

History

Air pollution has always accompanied civilizations. Pollution started from prehistoric times, when man created the first fires. According to a 1983 article in the journal Science, "soot" found on ceilings of prehistoric caves provides ample evidence of the high levels of pollution that was associated with inadequate ventilation of open fires."[4] Metal forging appears to be a key turning point in the creation of significant air pollution levels outside the home. Core samples of glaciers in Greenland indicate increases in pollution associated with Greek, Roman, and Chinese metal production.[5]

Urban pollution

The burning of coal and wood, and the presence of many horses in concentrated areas made the cities the primary sources of pollution. The Industrial Revolution brought an infusion of untreated chemicals and wastes into local streams that served as the water supply. King Edward I of England banned the burning of sea-coal by proclamation in London in 1272, after its smoke became a problem;[6][7] the fuel was so common in England that this earliest of names for it was acquired because it could be carted away from some shores by the wheelbarrow.

It was the Industrial Revolution that gave birth to environmental pollution as we know it today. London also recorded one of the earlier extreme cases of water quality problems with the Great Stink on the Thames of 1858, which led to construction of the London sewerage system soon afterward. Pollution issues escalated as population growth far exceeded viability of neighborhoods to handle their waste problem. Reformers began to demand sewer systems and clean water.[8]

In 1870, the sanitary conditions in Berlin were among the worst in Europe. August Bebel recalled conditions before a modern sewer system was built in the late 1870s:

Waste-water from the houses collected in the gutters running alongside the curbs and emitted a truly fearsome smell. There were no public toilets in the streets or squares. Visitors, especially women, often became desperate when nature called. In the public buildings the sanitary facilities were unbelievably primitive....As a metropolis, Berlin did not emerge from a state of barbarism into civilization until after 1870."[9]

The primitive conditions were intolerable for a world national capital, and the Imperial German government brought in its scientists, engineers, and urban planners to not only solve the deficiencies, but to forge Berlin as the world's model city. A British expert in 1906 concluded that Berlin represented "the most complete application of science, order and method of public life," adding "it is a marvel of civic administration, the most modern and most perfectly organized city that there is."[10]

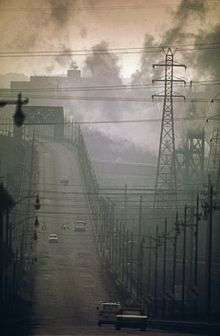

The emergence of great factories and consumption of immense quantities of coal gave rise to unprecedented air pollution and the large volume of industrial chemical discharges added to the growing load of untreated human waste. Chicago and Cincinnati were the first two American cities to enact laws ensuring cleaner air in 1881. Pollution became a major issue in the United States in the early twentieth century, as progressive reformers took issue with air pollution caused by coal burning, water pollution caused by bad sanitation, and street pollution caused by the 3 million horses who worked in American cities in 1900, generating large quantities of urine and manure. As historian Martin Melosi notes, the generation that first saw automobiles replacing the horses saw cars as "miracles of cleanliness".[11] By the 1940s, however, automobile-caused smog was a major issue in Los Angeles.[12]

Other cities followed around the country until early in the 20th century, when the short lived Office of Air Pollution was created under the Department of the Interior. Extreme smog events were experienced by the cities of Los Angeles and Donora, Pennsylvania in the late 1940s, serving as another public reminder.[13]

Air pollution would continue to be a problem in England, especially later during the industrial revolution, and extending into the recent past with the Great Smog of 1952. Awareness of atmospheric pollution spread widely after World War II, with fears triggered by reports of radioactive fallout from atomic warfare and testing.[14] Then a non-nuclear event – the Great Smog of 1952 in London – killed at least 4000 people.[15] This prompted some of the first major modern environmental legislation: the Clean Air Act of 1956.

Pollution began to draw major public attention in the United States between the mid-1950s and early 1970s, when Congress passed the Noise Control Act, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the National Environmental Policy Act.[16]

Severe incidents of pollution helped increase consciousness. PCB dumping in the Hudson River resulted in a ban by the EPA on consumption of its fish in 1974. National news stories in the late 1970s – especially the long-term dioxin contamination at Love Canal starting in 1947 and uncontrolled dumping in Valley of the Drums – led to the Superfund legislation of 1980.[17] The pollution of industrial land gave rise to the name brownfield, a term now common in city planning.

The development of nuclear science introduced radioactive contamination, which can remain lethally radioactive for hundreds of thousands of years. Lake Karachay – named by the Worldwatch Institute as the "most polluted spot" on earth – served as a disposal site for the Soviet Union throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Chelyabinsk, Russia, is considered the "Most polluted place on the planet".[18]

Nuclear weapons continued to be tested in the Cold War, especially in the earlier stages of their development. The toll on the worst-affected populations and the growth since then in understanding about the critical threat to human health posed by radioactivity has also been a prohibitive complication associated with nuclear power. Though extreme care is practiced in that industry, the potential for disaster suggested by incidents such as those at Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima pose a lingering specter of public mistrust. Worldwide publicity has been intense on those disasters.[19] Widespread support for test ban treaties has ended almost all nuclear testing in the atmosphere.[20]

International catastrophes such as the wreck of the Amoco Cadiz oil tanker off the coast of Brittany in 1978 and the Bhopal disaster in 1984 have demonstrated the universality of such events and the scale on which efforts to address them needed to engage. The borderless nature of atmosphere and oceans inevitably resulted in the implication of pollution on a planetary level with the issue of global warming. Most recently the term persistent organic pollutant (POP) has come to describe a group of chemicals such as PBDEs and PFCs among others. Though their effects remain somewhat less well understood owing to a lack of experimental data, they have been detected in various ecological habitats far removed from industrial activity such as the Arctic, demonstrating diffusion and bioaccumulation after only a relatively brief period of widespread use.

.jpg)

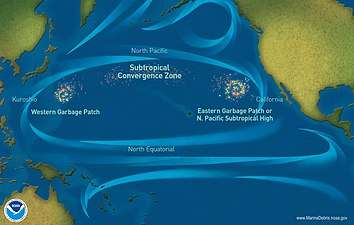

A much more recently discovered problem is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a huge concentration of plastics, chemical sludge and other debris which has been collected into a large area of the Pacific Ocean by the North Pacific Gyre. This is a less well known pollution problem than the others described above, but nonetheless has multiple and serious consequences such as increasing wildlife mortality, the spread of invasive species and human ingestion of toxic chemicals. Organizations such as 5 Gyres have researched the pollution and, along with artists like Marina DeBris, are working toward publicizing the issue.

Pollution introduced by light at night is becoming a global problem, more severe in urban centres, but nonetheless contaminating also large territories, far away from towns.[21]

Growing evidence of local and global pollution and an increasingly informed public over time have given rise to environmentalism and the environmental movement, which generally seek to limit human impact on the environment.

Forms of pollution

The major forms of pollution are listed below along with the particular contaminant relevant to each of them:

- Air pollution: the release of chemicals and particulates into the atmosphere. Common gaseous pollutants include carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and nitrogen oxides produced by industry and motor vehicles. Photochemical ozone and smog are created as nitrogen oxides and hydrocarbons react to sunlight. Particulate matter, or fine dust is characterized by their micrometre size PM10 to PM2.5.

- Electromagnetic pollution: the overabundance of electromagnetic radiation in their non-ionizing form, like radio waves, etc, that people are constantly exposed at, especially in large cities. It's still unknown whether or not those types of radiation have any effects on human health, though.

- Light pollution: includes light trespass, over-illumination and astronomical interference.

- Littering: the criminal throwing of inappropriate man-made objects, unremoved, onto public and private properties.

- Noise pollution: which encompasses roadway noise, aircraft noise, industrial noise as well as high-intensity sonar.

- Plastic pollution: involves the accumulation of plastic products and microplastics in the environment that adversely affects wildlife, wildlife habitat, or humans.

- Soil contamination occurs when chemicals are released by spill or underground leakage. Among the most significant soil contaminants are hydrocarbons, heavy metals, MTBE,[22] herbicides, pesticides and chlorinated hydrocarbons.

- Radioactive contamination, resulting from 20th century activities in atomic physics, such as nuclear power generation and nuclear weapons research, manufacture and deployment. (See alpha emitters and actinides in the environment.)

- Thermal pollution, is a temperature change in natural water bodies caused by human influence, such as use of water as coolant in a power plant.

- Visual pollution, which can refer to the presence of overhead power lines, motorway billboards, scarred landforms (as from strip mining), open storage of trash, municipal solid waste or space debris.

- Water pollution, by the discharge of wastewater from commercial and industrial waste (intentionally or through spills) into surface waters; discharges of untreated domestic sewage, and chemical contaminants, such as chlorine, from treated sewage; release of waste and contaminants into surface runoff flowing to surface waters (including urban runoff and agricultural runoff, which may contain chemical fertilizers and pesticides; also including human feces from open defecation – still a major problem in many developing countries); groundwater pollution from waste disposal and leaching into the ground, including from pit latrines and septic tanks; eutrophication and littering.

Pollutants

A pollutant is a waste material that pollutes air, water, or soil. Three factors determine the severity of a pollutant: its chemical nature, the concentration, the area affected and the persistence.

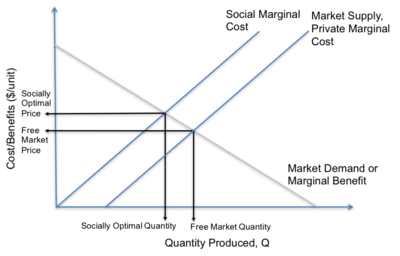

Cost of pollution

Pollution has a cost.[23][24][25] Manufacturing activities that cause air pollution impose health and clean-up costs on the whole of society, whereas the neighbors of an individual who chooses to fire-proof his home may benefit from a reduced risk of a fire spreading to their own homes. A manufacturing activity that causes air pollution is an example of a negative externality in production. A negative externality in production occurs “when a firm’s production reduces the well-being of others who are not compensated by the firm."[26] For example, if a laundry firm exists near a polluting steel manufacturing firm, there will be increased costs for the laundry firm because of the dirt and smoke produced by the steel manufacturing firm.[27] If external costs exist, such as those created by pollution, the manufacturer will choose to produce more of the product than would be produced if the manufacturer were required to pay all associated environmental costs. Because responsibility or consequence for self-directed action lies partly outside the self, an element of externalization is involved. If there are external benefits, such as in public safety, less of the good may be produced than would be the case if the producer were to receive payment for the external benefits to others. However, goods and services that involve negative externalities in production, such as those that produce pollution, tend to be over-produced and underpriced since the externality is not being priced into the market.[26]

Pollution can also create costs for the firms producing the pollution. Sometimes firms choose, or are forced by regulation, to reduce the amount of pollution that they are producing. The associated costs of doing this are called abatement costs, or marginal abatement costs if measured by each additional unit.[28] In 2005 pollution abatement capital expenditures and operating costs in the US amounted to nearly $27 billion.[29]

Socially optimal level of pollution

Society derives some indirect utility from pollution, otherwise there would be no incentive to pollute. This utility comes from the consumption of goods and services that create pollution. Therefore, it is important that policymakers attempt to balance these indirect benefits with the costs of pollution in order to achieve an efficient outcome.[30]

It is possible to use environmental economics to determine which level of pollution is deemed the social optimum. For economists, pollution is an “external cost and occurs only when one or more individuals suffer a loss of welfare,” however, there exists a socially optimal level of pollution at which welfare is maximized.[31] This is because consumers derive utility from the good or service manufactured, which will outweigh the social cost of pollution until a certain point. At this point the damage of one extra unit of pollution to society, the marginal cost of pollution, is exactly equal to the marginal benefit of consuming one more unit of the good or service.[32]

In markets with pollution, or other negative externalities in production, the free market equilibrium will not account for the costs of pollution on society. If the social costs of pollution are higher than the private costs incurred by the firm, then the true supply curve will be higher. The point at which the social marginal cost and market demand intersect gives the socially optimal level of pollution. At this point, the quantity will be lower and the price will be higher in comparison to the free market equilibrium.[32] Therefore, the free market outcome could be considered a market failure because it “does not maximize efficiency”.[26]

This model can be used as a basis to evaluate different methods of internalizing the externality. Some examples include tariffs, a carbon tax and cap and trade systems.

Sources and causes

Air pollution comes from both natural and human-made (anthropogenic) sources. However, globally human-made pollutants from combustion, construction, mining, agriculture and warfare are increasingly significant in the air pollution equation.[33]

Motor vehicle emissions are one of the leading causes of air pollution.[34][35][36] China, United States, Russia, India[37] Mexico, and Japan are the world leaders in air pollution emissions. Principal stationary pollution sources include chemical plants, coal-fired power plants, oil refineries,[38] petrochemical plants, nuclear waste disposal activity, incinerators, large livestock farms (dairy cows, pigs, poultry, etc.), PVC factories, metals production factories, plastics factories, and other heavy industry. Agricultural air pollution comes from contemporary practices which include clear felling and burning of natural vegetation as well as spraying of pesticides and herbicides[39]

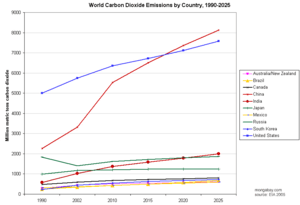

About 400 million metric tons of hazardous wastes are generated each year.[40] The United States alone produces about 250 million metric tons.[41] Americans constitute less than 5% of the world's population, but produce roughly 25% of the world's CO

2,[42] and generate approximately 30% of world's waste.[43][44] In 2007, China overtook the United States as the world's biggest producer of CO

2,[45] while still far behind based on per capita pollution (ranked 78th among the world's nations).[46]

In February 2007, a report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), representing the work of 2,500 scientists, economists, and policymakers from more than 120 countries, confirmed that humans have been the primary cause of global warming since 1950. Humans have ways to cut greenhouse gas emissions and avoid the consequences of global warming, a major climate report concluded. But to change the climate, the transition from fossil fuels like coal and oil needs to occur within decades, according to the final report this year from the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).[47]

Some of the more common soil contaminants are chlorinated hydrocarbons (CFH), heavy metals (such as chromium, cadmium – found in rechargeable batteries, and lead – found in lead paint, aviation fuel and still in some countries, gasoline), MTBE, zinc, arsenic and benzene. In 2001 a series of press reports culminating in a book called Fateful Harvest unveiled a widespread practice of recycling industrial byproducts into fertilizer, resulting in the contamination of the soil with various metals. Ordinary municipal landfills are the source of many chemical substances entering the soil environment (and often groundwater), emanating from the wide variety of refuse accepted, especially substances illegally discarded there, or from pre-1970 landfills that may have been subject to little control in the U.S. or EU. There have also been some unusual releases of polychlorinated dibenzodioxins, commonly called dioxins for simplicity, such as TCDD.[48]

Pollution can also be the consequence of a natural disaster. For example, hurricanes often involve water contamination from sewage, and petrochemical spills from ruptured boats or automobiles. Larger scale and environmental damage is not uncommon when coastal oil rigs or refineries are involved. Some sources of pollution, such as nuclear power plants or oil tankers, can produce widespread and potentially hazardous releases when accidents occur.

In the case of noise pollution the dominant source class is the motor vehicle, producing about ninety percent of all unwanted noise worldwide.

Effects

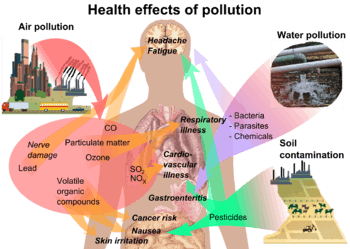

Human health

Adverse air quality can kill many organisms, including humans. Ozone pollution can cause respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, throat inflammation, chest pain, and congestion. Water pollution causes approximately 14,000 deaths per day, mostly due to contamination of drinking water by untreated sewage in developing countries. An estimated 500 million Indians have no access to a proper toilet,[52][53] Over ten million people in India fell ill with waterborne illnesses in 2013, and 1,535 people died, most of them children.[54] Nearly 500 million Chinese lack access to safe drinking water.[55] A 2010 analysis estimated that 1.2 million people died prematurely each year in China because of air pollution.[56] The high smog levels China has been facing for a long time can do damage to civilians' bodies and cause different diseases.[57] The WHO estimated in 2007 that air pollution causes half a million deaths per year in India.[58] Studies have estimated that the number of people killed annually in the United States could be over 50,000.[59]

Oil spills can cause skin irritations and rashes. Noise pollution induces hearing loss, high blood pressure, stress, and sleep disturbance. Mercury has been linked to developmental deficits in children and neurologic symptoms. Older people are majorly exposed to diseases induced by air pollution. Those with heart or lung disorders are at additional risk. Children and infants are also at serious risk. Lead and other heavy metals have been shown to cause neurological problems. Chemical and radioactive substances can cause cancer and as well as birth defects.

An October 2017 study by the Lancet Commission on Pollution and Health found that global pollution, specifically toxic air, water, soils and workplaces, kills nine million people annually, which is triple the number of deaths caused by AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria combined, and 15 times higher than deaths caused by wars and other forms of human violence.[60] The study concluded that "pollution is one of the great existential challenges of the Anthropocene era. Pollution endangers the stability of the Earth’s support systems and threatens the continuing survival of human societies."[3]

Environment

Pollution has been found to be present widely in the environment. There are a number of effects of this:

- Biomagnification describes situations where toxins (such as heavy metals) may pass through trophic levels, becoming exponentially more concentrated in the process.

- Carbon dioxide emissions cause ocean acidification, the ongoing decrease in the pH of the Earth's oceans as CO

2 becomes dissolved. - The emission of greenhouse gases leads to global warming which affects ecosystems in many ways.

- Invasive species can outcompete native species and reduce biodiversity. Invasive plants can contribute debris and biomolecules (allelopathy) that can alter soil and chemical compositions of an environment, often reducing native species competitiveness.

- Nitrogen oxides are removed from the air by rain and fertilise land which can change the species composition of ecosystems.

- Smog and haze can reduce the amount of sunlight received by plants to carry out photosynthesis and leads to the production of tropospheric ozone which damages plants.

- Soil can become infertile and unsuitable for plants. This will affect other organisms in the food web.

- Sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides can cause acid rain which lowers the pH value of soil.

- Organic pollution of watercourses can deplete oxygen levels and reduce species diversity.

Environmental health information

The Toxicology and Environmental Health Information Program (TEHIP)[61] at the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) maintains a comprehensive toxicology and environmental health web site that includes access to resources produced by TEHIP and by other government agencies and organizations. This web site includes links to databases, bibliographies, tutorials, and other scientific and consumer-oriented resources. TEHIP also is responsible for the Toxicology Data Network (TOXNET)[62] an integrated system of toxicology and environmental health databases that are available free of charge on the web.

TOXMAP is a Geographic Information System (GIS) that is part of TOXNET. TOXMAP uses maps of the United States to help users visually explore data from the United States Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) Toxics Release Inventory and Superfund Basic Research Programs.

School outcomes

A 2019 paper linked pollution to adverse school outcomes for children.[63]

Regulation and monitoring

To protect the environment from the adverse effects of pollution, many nations worldwide have enacted legislation to regulate various types of pollution as well as to mitigate the adverse effects of pollution.

Pollution control

Pollution control is a term used in environmental management. It means the control of emissions and effluents into air, water or soil. Without pollution control, the waste products from overconsumption, heating, agriculture, mining, manufacturing, transportation and other human activities, whether they accumulate or disperse, will degrade the environment. In the hierarchy of controls, pollution prevention and waste minimization are more desirable than pollution control. In the field of land development, low impact development is a similar technique for the prevention of urban runoff.

Pollution control devices

- Air pollution control

- Thermal oxidizer

- Dust collection systems

- Scrubbers

- Sewage treatment

- Sedimentation (Primary treatment)

- Activated sludge biotreaters (Secondary treatment; also used for industrial wastewater)

- Aerated lagoons

- Constructed wetlands (also used for urban runoff)

- Industrial wastewater treatment

- API oil-water separators[38][68]

- Biofilters

- Dissolved air flotation (DAF)

- Powdered activated carbon treatment

- Ultrafiltration

- Vapor recovery systems

- Phytoremediation

Perspectives

The earliest precursor of pollution generated by life forms would have been a natural function of their existence. The attendant consequences on viability and population levels fell within the sphere of natural selection. These would have included the demise of a population locally or ultimately, species extinction. Processes that were untenable would have resulted in a new balance brought about by changes and adaptations. At the extremes, for any form of life, consideration of pollution is superseded by that of survival.

For humankind, the factor of technology is a distinguishing and critical consideration, both as an enabler and an additional source of byproducts. Short of survival, human concerns include the range from quality of life to health hazards. Since science holds experimental demonstration to be definitive, modern treatment of toxicity or environmental harm involves defining a level at which an effect is observable. Common examples of fields where practical measurement is crucial include automobile emissions control, industrial exposure (e.g. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) PELs), toxicology (e.g. LD50), and medicine (e.g. medication and radiation doses).

"The solution to pollution is dilution", is a dictum which summarizes a traditional approach to pollution management whereby sufficiently diluted pollution is not harmful.[69][70] It is well-suited to some other modern, locally scoped applications such as laboratory safety procedure and hazardous material release emergency management. But it assumes that the diluent is in virtually unlimited supply for the application or that resulting dilutions are acceptable in all cases.

Such simple treatment for environmental pollution on a wider scale might have had greater merit in earlier centuries when physical survival was often the highest imperative, human population and densities were lower, technologies were simpler and their byproducts more benign. But these are often no longer the case. Furthermore, advances have enabled measurement of concentrations not possible before. The use of statistical methods in evaluating outcomes has given currency to the principle of probable harm in cases where assessment is warranted but resorting to deterministic models is impractical or infeasible. In addition, consideration of the environment beyond direct impact on human beings has gained prominence.

Yet in the absence of a superseding principle, this older approach predominates practices throughout the world. It is the basis by which to gauge concentrations of effluent for legal release, exceeding which penalties are assessed or restrictions applied. One such superseding principle is contained in modern hazardous waste laws in developed countries, as the process of diluting hazardous waste to make it non-hazardous is usually a regulated treatment process.[71] Migration from pollution dilution to elimination in many cases can be confronted by challenging economical and technological barriers.

Greenhouse gases and global warming

Carbon dioxide, while vital for photosynthesis, is sometimes referred to as pollution, because raised levels of the gas in the atmosphere are affecting the Earth's climate. Disruption of the environment can also highlight the connection between areas of pollution that would normally be classified separately, such as those of water and air. Recent studies have investigated the potential for long-term rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide to cause slight but critical increases in the acidity of ocean waters, and the possible effects of this on marine ecosystems.

Rossby waves and surface air pollution

Air pollution fluctuations have been known to strongly depend on the weather dynamics. A recent study developed a multi-layered network analysis and detected strong interlinks between the geopotential height of the upper air ( 5 km) and surface air pollution in both China and the USA.[74] This study indicates that Rossby waves significantly affect air pollution fluctuations through the development of cyclone and anticyclone systems, and further affect the local stability of the air and the winds. The Rossby waves impact on air pollution has been observed in the daily fluctuations in surface air pollution. Thus, the impact of Rossby waves on human life is significant and rapid warming of the Arctic could slow down Rossby waves, thus increasing human health risks.

Most polluting industries

The Pure Earth, an international non-for-profit organization dedicated to eliminating life-threatening pollution in the developing world, issues an annual list of some of the world's most polluting industries.[75]

- Lead-Acid Battery Recycling

- Industrial Mining and Ore Processing

- Lead Smelting

- Tannery Operations

- Artisanal Small-Scale Gold Mining

- Industrial/Municipal Dumpsites

- Industrial Estates

- Chemical Manufacturing

- Product Manufacturing

- Dye Industry

A 2018 report by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy and GRAIN says that the meat and dairy industries are poised to surpass the oil industry as the world's worst polluters.[76]

World’s worst polluted places

Pure Earth issues an annual list of some of the world's worst polluted places.[77]

- Agbogbloshie, Ghana

- Chernobyl, Ukraine

- Citarum River, Indonesia

- Dzershinsk, Russia

- Hazaribagh, Bangladesh

- Kabwe, Zambia

- Kalimantan, Indonesia

- Matanza Riachuelo, Argentina

- Niger River Delta, Nigeria

- Norilsk, Russia

See also

- Anthropocene

- Biological contamination

- Chemical contamination

- Environmental health

- Environmental racism

- Hazardous Substances Data Bank

- Marine pollution

- Overpopulation

- Pollutant release and transfer register

- Pollutants

- Polluter pays principle

- Pollution haven hypothesis

- Regulation of greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act

- Rossby wave

- Plastic pollution

|

|

|

Other |

References

- "Pollution – Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. 2010-08-13. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- Beil, Laura (15 November 2017). "Pollution killed 9 million people in 2015". Sciencenews.org. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- Carrington, Damian (October 20, 2017). "Global pollution kills 9m a year and threatens 'survival of human societies'". The Guardian. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- Spengler, John D.; Sexton, K. A. (1983). "Indoor Air Pollution: A Public Health Perspective". Science. 221 (4605): 9–17 [p. 9]. Bibcode:1983Sci...221....9S. doi:10.1126/science.6857273. PMID 6857273.

- Hong, Sungmin; et al. (1996). "History of Ancient Copper Smelting Pollution During Roman and Medieval Times Recorded in Greenland Ice". Science. 272 (5259): 246–249 [p. 248]. Bibcode:1996Sci...272..246H. doi:10.1126/science.272.5259.246.

- David Urbinato (Summer 1994). "London's Historic "Pea-Soupers"". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 2006-08-02.

- "Deadly Smog". PBS. 2003-01-17. Retrieved 2006-08-02.

- Lee Jackson, Dirty Old London: The Victorian Fight Against Filth (2014)

- Cited in David Clay Large, Berlin (2000) pp 17-18

- Hugh Chisholm (1910). The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th edition. p. 786.

- Patrick Allitt, A Climate of Crisis: America in the Age of Environmentalism (2014) p 206

- Jeffry M. Diefendorf; Kurkpatrick Dorsey (2009). City, Country, Empire: Landscapes in Environmental History. University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 44–49. ISBN 978-0-8229-7277-8.

- Fleming, James R.; Knorr, Bethany R. "History of the Clean Air Act". American Meteorological Society. Retrieved 2006-02-14.

- Patrick Allitt, A Climate of Crisis: America in the Age of Environmentalism (2014) pp. 15–21

- 1952: London fog clears after days of chaos (BBC News)

- John Tarantino. "Environmental Issues". The Environmental Blog. Archived from the original on 2012-01-11. Retrieved 2011-12-10.

- Judith A. Layzer, "Love Canal: hazardous waste and politics of fear" in Layzer, The Environmental Case (CQ Press, 2012) pp. 56–82.

- Lenssen, "Nuclear Waste: The Problem that Won't Go Away", Worldwatch Institute, Washington, D.C., 1991: 15.

- Friedman, Sharon M. (2011). "Three Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima: An analysis of traditional and new media coverage of nuclear accidents and radiation". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 67 (5): 55–65. Bibcode:2011BuAtS..67e..55F. doi:10.1177/0096340211421587.

- Jonathan Medalia, Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty: Background and Current Developments (Diane Publishing, 2013.)

- Falchi, Fabio; Cinzano, Pierantonio; Duriscoe, Dan; Kyba, Christopher C. M.; Elvidge, Christopher D.; Baugh, Kimberly; Portnov, Boris A.; Rybnikova, Nataliya A.; Furgoni, Riccardo (2016-06-01). "The new world atlas of artificial night sky brightness". Science Advances. 2 (6): e1600377. arXiv:1609.01041. Bibcode:2016SciA....2E0377F. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1600377. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 4928945. PMID 27386582.

- Concerns about MTBE from U.S. EPA website

- The staggering economic cost of air pollution By Chelsea Harvey, Washington Post, January 29, 2016

- Freshwater Pollution Costs US At Least $4.3 Billion A Year, Science Daily, November 17, 2008

- The human cost of China's untold soil pollution problem, The Guardian, Monday 30 June 2014 11.53 EDT

- Jonathan., Gruber (2013). Public finance and public policy (4th ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4292-7845-4. OCLC 819816787.

- D., Kolstad, Charles (2011). Environmental economics (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-973264-7. OCLC 495996799.

- "Abatement and Marginal Abatement Cost (MAC)". www.econport.org. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

- EPA,OA,OP,NCEE, US. "Pollution Abatement Costs and Expenditures: 2005 Survey | US EPA". US EPA. Retrieved 2018-03-07.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "18.1 Maximizing the Net Benefits of Pollution | Principles of Economics". open.lib.umn.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-07.

- William), Pearce, David W. (David (1990). Economics of natural resources and the environment. Turner, R. Kerry. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-3987-0. OCLC 20170416.

- R., Krugman, Paul (2013). Microeconomics. Wells, Robin. (3rd ed.). New York: Worth Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4292-8342-7. OCLC 796082268.

- Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, 1972

- Environmental Performance Report 2001 Archived 2007-11-12 at the Wayback Machine (Transport, Canada website page)

- State of the Environment, Issue: Air Quality (Australian Government website page)

- "Pollution". 11 April 2007. Archived from the original on 11 April 2007. Retrieved 1 December 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Laboratory, Oak Ridge National. "Top 20 Emitting Countries by Total Fossil-Fuel CO2 Emissions for 2009". Cdiac.ornl.gov. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- Beychok, Milton R. (1967). Aqueous Wastes from Petroleum and Petrochemical Plants (1st ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-07189-1. LCCN 67019834.

- Silent Spring, R Carlson, 1962

- "Pollution Archived 2009-10-21 at the Wayback Machine". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2009.

- "Solid Waste – The Ultimate Guide". Ppsthane.com. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- "Revolutionary CO

2 maps zoom in on greenhouse gas sources". Purdue University. April 7, 2008. - "Waste Watcher" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- Alarm sounds on US population boom. August 31, 2006. The Boston Globe.

- "China overtakes US as world's biggest CO

2 emitter". Guardian.co.uk. June 19, 2007. - "Ranking of the world's countries by 2008 per capita fossil-fuel CO2 emission rates.". CDIAC. 2008.

- "Global Warming Can Be Stopped, World Climate Experts Say". News.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- Beychok, Milton R. (January 1987). "A data base for dioxin and furan emissions from refuse incinerators". Atmospheric Environment. 21 (1): 29–36. Bibcode:1987AtmEn..21...29B. doi:10.1016/0004-6981(87)90267-8.

- World Resources Institute: August 2008 Monthly Update: Air Pollution's Causes, Consequences and Solutions Archived 2009-05-01 at the Wayback Machine Submitted by Matt Kallman on Wed, 2008-08-20 18:22. Retrieved on April 17, 2009

- waterhealthconnection.org Overview of Waterborne Disease Trends Archived 2008-09-05 at the Wayback Machine By Patricia L. Meinhardt, MD, MPH, MA, Author. Retrieved on April 16, 2009

- Pennsylvania State University > Potential Health Effects of Pesticides. Archived 2013-08-11 at the Wayback Machine by Eric S. Lorenz. 2007.

- "Indian Pediatrics". Retrieved May 1, 2008.

- "UNICEF ROSA – Young child survival and development – Water and Sanitation". Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- Isalkar, Umesh (29 July 2014). "Over 1,500 lives lost to diarrhoea in 2013, delay in treatment blamed". The Times of India. Indiatimes. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- "As China Roars, Pollution Reaches Deadly Extremes". The New York Times. August 26, 2007.

- Wong, Edward (1 April 2013). "Air Pollution Linked to 1.2 Million Deaths in China". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- Maji, Kamal Jyoti; Arora, Mohit; Dikshit, Anil Kumar (2017-04-01). "Burden of disease attributed to ambient PM2.5 and PM10 exposure in 190 cities in China". Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 24 (12): 11559–11572. doi:10.1007/s11356-017-8575-7. ISSN 0944-1344. PMID 28321701.

- Chinese Air Pollution Deadliest in World, Report Says. National Geographic News. July 9, 2007.

- David, Michael, and Caroline. "Air Pollution – Effects". Library.thinkquest.org. Retrieved 2010-08-26.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Stanglin, Doug (October 20, 2017). "Global pollution is the world's biggest killer and a threat to survival of mankind, study finds". USA Today. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- "SIS.nlm.nih.gov". SIS.nlm.nih.gov. 2010-08-12. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- "Toxnet.nlm.nih.gov". Toxnet.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- Heissel, Jennifer; Persico, Claudia; Simon, David (2019). "Does Pollution Drive Achievement? The Effect of Traffic Pollution on Academic Performance". doi:10.3386/w25489. hdl:10945/61763. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Zivin, Joshua Graff; Neidell, Matthew (2012-12-01). "The Impact of Pollution on Worker Productivity". American Economic Review. 102 (7): 3652–3673. doi:10.1257/aer.102.7.3652. ISSN 0002-8282. PMC 4576916. PMID 26401055.

- Li, Teng; Liu, Haoming; Salvo, Alberto (2015-05-29). "Severe Air Pollution and Labor Productivity". Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network. SSRN 2581311. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Neidell, Matthew; Gross, Tal; Graff Zivin, Joshua; Chang, Tom Y. (2019). "The Effect of Pollution on Worker Productivity: Evidence from Call Center Workers in China" (PDF). American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 11 (1): 151–172. doi:10.1257/app.20160436. ISSN 1945-7782.

- Salvo, Alberto; Liu, Haoming; He, Jiaxiu (2019). "Severe Air Pollution and Labor Productivity: Evidence from Industrial Towns in China". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 11 (1): 173–201. doi:10.1257/app.20170286. ISSN 1945-7782.

- American Petroleum Institute (API) (February 1990). Management of Water Discharges: Design and Operations of Oil–Water Separators (1st ed.). American Petroleum Institute.

- The 'Solution' to Pollution Is Still 'Dilution', archived from the original on May 4, 2008, retrieved 2013-07-22CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- "What is required". Clean Ocean Foundation. 2001. Archived from the original on 2006-05-19. Retrieved 2006-02-14.

- "The Mixture Rule under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act" (PDF). U.S. Dept. of Energy. 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-26. Retrieved 2012-04-10.

- World Carbon Dioxide Emissions Archived 2008-03-26 at the Wayback Machine (Table 1, Report DOE/EIA-0573, 2004, Energy Information Administration)

- Carbon dioxide emissions chart (graph on Mongabay website page based on Energy Information Administration's tabulated data)

- Y Zhang, J Fan, X Chen, Y Ashkenazy, S Havlin (2019). "Significant Impact of Rossby Waves on Air Pollution Detected by Network Analysis". Geophysical Research Letters. 46 (21): 12476–12485. arXiv:1903.02256. doi:10.1029/2019GL084649.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "World's Worst Pollution Problems" (PDF).

- Gabbatiss, Josh (July 18, 2018). "Meat and dairy companies to surpass oil industry as world's biggest polluters, report finds". The Independent. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- The World's Most Polluted Places: The Top Ten of the Dirty Thirty (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-10-11, retrieved 2013-12-10

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Pollution |

| Look up pollution in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pollution. |

- OEHHA proposition 65 list

- National Toxicology Program – from US National Institutes of Health. Reports and studies on how pollutants affect people

- TOXNET – NIH databases and reports on toxicology

- TOXMAP – Geographic Information System (GIS) that uses maps of the United States to help users visually explore data from the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Toxics Release Inventory and Superfund Basic Research Programs

- EPA.gov – manages Superfund sites and the pollutants in them (CERCLA). Map the EPA Superfund

- Toxic Release Inventory – tracks how much waste US companies release into the water and air. Gives permits for releasing specific quantities of these pollutants each year. Map EPA's Toxic Release Inventory

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry – Top 20 pollutants, how they affect people, what US industries use them and the products in which they are found

- Toxicology Tutorials from the National Library of Medicine – resources to review human toxicology.

- World's Worst Polluted Places 2007, according to the Blacksmith Institute

- The World's Most Polluted Places at Time.com (a division of Time Magazine)

- Chelyabinsk: The Most Contaminated Spot on the Planet Documentary Film by Slawomir Grünberg (1996)

- Nieman Reports | Tracking Toxics When the Data Are Polluted