Plastic pollution

Plastic pollution is the accumulation of plastic objects and particles (e.g. plastic bottles, bags and microbeads) in the Earth's environment that adversely affects wildlife, wildlife habitat, and humans.[1][2] Plastics that act as pollutants are categorized into micro-, meso-, or macro debris, based on size.[3] Plastics are inexpensive and durable, and as a result levels of plastic production by humans are high.[4] However, the chemical structure of most plastics renders them resistant to many natural processes of degradation and as a result they are slow to degrade.[5] Together, these two factors have led to a high prominence of plastic pollution in the environment.

Plastic pollution can afflict land, waterways and oceans. It is estimated that 1.1 to 8.8 million tonnes of plastic waste enters the ocean from coastal communities each year.[6] Living organisms, particularly marine animals, can be harmed either by mechanical effects, such as entanglement in plastic objects, problems related to ingestion of plastic waste, or through exposure to chemicals within plastics that interfere with their physiology. Effects on humans include disruption of various hormonal mechanisms.

As of 2018, about 380 million tonnes of plastic is produced worldwide each year. From the 1950s up to 2018, an estimated 6.3 billion tonnes of plastic has been produced worldwide, of which an estimated 9% has been recycled and another 12% has been incinerated.[7] This large amount of plastic waste enters the environment, with studies suggesting that the bodies of 90% of seabirds contain plastic debris.[8][9] In some areas there have been significant efforts to reduce the prominence of free range plastic pollution, through reducing plastic consumption, litter cleanup, and promoting plastic recycling.[10][11]

Some researchers suggest that by 2050 there could be more plastic than fish in the oceans by weight.[12]

Causes

The trade in plastic waste has been identified as "a main culprit" of marine litter.[lower-alpha 1] Countries importing the waste plastics often lack the capacity to process all the material. As a result, the United Nations has imposed a ban on waste plastic trade unless it meets certain criteria.[lower-alpha 2]

Types of plastic debris

There are three major forms of plastic that contribute to plastic pollution: microplastics as well as mega- and macro-plastics. Mega- and micro plastics have accumulated in highest densities in the Northern Hemisphere, concentrated around urban centers and water fronts. Plastic can be found off the coast of some islands because of currents carrying the debris. Both mega- and macro-plastics are found in packaging, footwear, and other domestic items that have been washed off of ships or discarded in landfills. Fishing-related items are more likely to be found around remote islands.[14][15] These may also be referred to as micro-, meso-, and macro debris.

Plastic debris is categorized as either primary or secondary. Primary plastics are in their original form when collected. Examples of these would be bottle caps, cigarette butts, and microbeads.[16] Secondary plastics, on the other hand, account for smaller plastics that have resulted from the degradation of primary plastics.[17]

Microdebris

Microdebris are plastic pieces between 2 mm and 5 mm in size.[15] Plastic debris that starts off as meso- or macrodebris can become microdebris through degradation and collisions that break it down into smaller pieces.[3] Microdebris is more commonly referred to as nurdles.[3] Nurdles are recycled to make new plastic items, but they easily end up released into the environment during production because of their small size. They often end up in ocean waters through rivers and streams.[3] Microdebris that come from cleaning and cosmetic products are also referred to as scrubbers. Because microdebris and scrubbers are so small in size, filter-feeding organisms often consume them.[3]

Nurdles enter the ocean by means of spills during transportation or from land based sources. The Ocean Conservancy reported that China, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam dump more plastic in the sea than all other countries combined.[18] It is estimated that 10% of the plastics in the ocean are nurdles, making them one of the most common types of plastic pollution, along with plastic bags and food containers.[19][20] These micro-plastics can accumulate in the oceans and allow for the accumulation of Persistent Bio-accumulating Toxins such as bisphenol A, polystyrene, DDT, and PCB's which are hydrophobic in nature and can cause adverse health affects.[21][22]

A 2004 study by Richard Thompson from the University of Plymouth, UK, found a great amount of microdebris on the beaches and waters in Europe, the Americas, Australia, Africa, and Antarctica.[5] Thompson and his associates found that plastic pellets from both domestic and industrial sources were being broken down into much smaller plastic pieces, some having a diameter smaller than human hair.[5] If not ingested, this microdebris floats instead of being absorbed into the marine environment. Thompson predicts there may be 300,000 plastic items per square kilometre of sea surface and 100,000 plastic particles per square kilometre of seabed.[5] International pellet watch collected samples of polythene pellets from 30 beaches from 17 countries which were then analysed for organic micro-pollutants. It was found that pellets found on beaches in America, Vietnam and southern Africa contained compounds from pesticides suggesting a high use of pesticides in the areas.[23]

Macrodebris

Plastic debris is categorized as macrodebris when it is larger than 20 mm. These include items such as plastic grocery bags.[3] Macrodebris are often found in ocean waters, and can have a serious impact on the native organisms. Fishing nets have been prime pollutants. Even after they have been abandoned, they continue to trap marine organisms and other plastic debris. Eventually, these abandoned nets become too difficult to remove from the water because they become too heavy, having grown in weight up to 6 tonnes.[3]

Plastic production

Decomposition of plastics

Plastics themselves contribute to approximately 10% of discarded waste. Many kinds of plastics exist depending on their precursors and the method for their polymerization. Depending on their chemical composition, plastics and resins have varying properties related to contaminant absorption and adsorption. Polymer degradation takes much longer as a result of saline environments and the cooling effect of the sea. These factors contribute to the persistence of plastic debris in certain environments.[15] Recent studies have shown that plastics in the ocean decompose faster than was once thought, due to exposure to sun, rain, and other environmental conditions, resulting in the release of toxic chemicals such as bisphenol A. However, due to the increased volume of plastics in the ocean, decomposition has slowed down.[24] The Marine Conservancy has predicted the decomposition rates of several plastic products. It is estimated that a foam plastic cup will take 50 years, a plastic beverage holder will take 400 years, a disposable nappy will take 450 years, and fishing line will take 600 years to degrade.[5]

Persistent organic pollutants

It was estimated that global production of plastics is approximately 250 mt/yr. Their abundance has been found to transport persistent organic pollutants, also known as POPs. These pollutants have been linked to an increased distribution of algae associated with red tides.[15]

Commercial pollutants

In 2019, the group Break Free From Plastic organized over 70,000 volunteers in 51 countries to collect and identify plastic waste. These volunteers collected over "59,000 plastic bags, 53,000 sachets and 29,000 plastic bottles," as reported by The Guardian. Nearly half of the items were identifiable by consumer brands. The most common brands were Coca-Cola, Nestlé, and Pepsico.[25][26]

Major plastic polluter countries

Mismanaged plastic waste polluters

Top 12 mismanaged plastic waste polluters

In 2018 approximate 513 million tonnes of plastics wind up in the oceans every year out of which the 83,1% is from the following 20 countries: China is the most mismanaged plastic waste polluter leaving in the sea the 27.7% of the world total, second Indonesia with the 10.1%, third Philippines with 5.9%, fourth Vietnam with 5.8%, fifth Sri Lanka 5.0%, sixth Thailand with 3.2%, seventh Egypt with 3.0%, eighth Malaysia with 2.9%, ninth Nigeria with 2.7%, tenth Bangladesh with 2.5%, eleventh South Africa with 2.0%, twelfth India with 1.9%, thirteenth Algeria with 1.6%, fourteenth Turkey with 1.5%, fifteenth Pakistan with 1.5%, sixteenth Brazil with 1.5%, seventeenth Myanmar with 1.4%, eighteenth Morocco with 1.0%, nineteenth North Korea with 1.0%, twentieth United States with 0.9%. The rest of world's countries combined wind up the 16.9% of the mismanaged plastic waste in the oceans, according to a study published by Science, Jambeck et al (2015).[6][27][28]

All the European Union countries combined would rank eighteenth on the list.[6][27]

A 2019 study calculated the mismanaged plastic waste, in millions of metric tonnes (Mt) per year:

- 52 Mt - Asia

- 17 Mt - Africa

- 7.9 Mt - Latin America & Caribbean

- 3.3 Mt - Europe

- 0.3 Mt - US & Canada

- 0.1 Mt - Oceania (Australia, New Zealand, etc.)[29]

Total plastic waste polluters

Around 275 million tonnes of plastic waste is generated each year around the world; between 4.8 million and 12.7 million tonnes is dumped into the sea. About 60% of the plastic waste in the ocean comes from the following top 5 countries.[30] The table below list the top 20 plastic waste polluting countries in 2010 according to a study published by Science, Jambeck et al (2015).[6][27]

| Position | Country | Plastic pollution (in 1000 tonnes per year) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | China | 8820 |

| 2 | Indonesia | 3220 |

| 3 | Philippines | 1880 |

| 4 | Vietnam | 1830 |

| 5 | Sri Lanka | 1590 |

| 6 | Thailand | 1030 |

| 7 | Egypt | 970 |

| 8 | Malaysia | 940 |

| 9 | Nigeria | 850 |

| 10 | Bangladesh | 790 |

| 11 | South Africa | 630 |

| 12 | India | 600 |

| 13 | Algeria | 520 |

| 14 | Turkey | 490 |

| 15 | Pakistan | 480 |

| 16 | Brazil | 470 |

| 17 | Myanmar | 460 |

| 18 | Morocco | 310 |

| 19 | North Korea | 300 |

| 20 | United States | 280 |

All the European Union countries combined would rank eighteenth on the list.[6][27]

In a study published by Environmental Science & Technology, Schmidt et al (2017) calculated that 10 rivers: two in Africa (the Nile and the Niger) and eight in Asia (the Ganges, Indus, Yellow, Yangtze, Hai He, Pearl, Mekong and Amur) "transport 88–95% of the global plastics load into the sea.".[31][32][33][34]

The Caribbean Islands are the biggest plastic polluters per capita in the world. Trinidad and Tobago produces 1.5 kilograms of waste per capita per day, is the biggest plastic polluter per capita in the world. At least 0.19 kg per person per day of Trinidad and Tobago's plastic debris end up in the ocean, or for example Saint Lucia which generates more than four times the amount of plastic waste per capita as China and is responsible for 1.2 times more improperly disposed plastic waste per capita than China. Of the top thirty global polluters per capita, ten are from the Caribbean region. These are Trinidad and Tobago, Antigua and Barbuda, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Guyana, Barbados, Saint Lucia, Bahamas, Grenada, Anguilla and Aruba, according to a set of studies summarized by Forbes (2019).[35]

Effects on the environment

The distribution of plastic debris is highly variable as a result of certain factors such as wind and ocean currents, coastline geography, urban areas, and trade routes. Human population in certain areas also plays a large role in this. Plastics are more likely to be found in enclosed regions such as the Caribbean. It serves as a means of distribution of organisms to remote coasts that are not their native environments. This could potentially increase the variability and dispersal of organisms in specific areas that are less biologically diverse. Plastics can also be used as vectors for chemical contaminants such as persistent organic pollutants and heavy metals.[15]

Plastic pollution as a cause of climate change

In 2019 a new report "Plastic and Climate" was published. According to the report, in 2019, production and incineration of plastic will contribute greenhouse gases in the equivalent of 850 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO

2) to the atmosphere. In current trend, annual emissions from these sources will grow to 1.34 billion tonnes by 2030. By 2050 plastic could emit 56 billion tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions, as much as 14 percent of the earth's remaining carbon budget.[36] By 2100 it will emit 260 billion tonnes, more than half of the carbon budget. Those are emission from production, transportation, incineration, but there are also releases of methane and effects on phytoplankton.[37]

Effects of plastic on land

Plastic pollution on land poses a threat to the plants and animals – including humans who are based on the land.[38] Estimates of the amount of plastic concentration on land are between four and twenty three times that of the ocean. The amount of plastic poised on the land is greater and more concentrated than that in the water.[39] Mismanaged plastic waste ranges from 60 percent in East Asia and Pacific to one percent in North America. The percentage of mismanaged plastic waste reaching the ocean annually and thus becoming plastic marine debris is between one third and one half the total mismanaged waste for that year.[40][41]

Chlorinated plastic can release harmful chemicals into the surrounding soil, which can then seep into groundwater or other surrounding water sources and also the ecosystem of the world.[42] This can cause serious harm to the species that drink the water.

Plastic pollution in tap water

A 2017 study found that 83% of tap water samples taken around the world contained plastic pollutants.[43][44] This was the first study to focus on global drinking water pollution with plastics,[45] and showed that with a contamination rate of 94%, tap water in the United States was the most polluted, followed by Lebanon and India. European countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany and France had the lowest contamination rate, though still as high as 72%.[43] This means that people may be ingesting between 3,000 and 4,000 microparticles of plastic from tap water per year.[45] The analysis found particles of more than 2.5 microns in size, which is 2500 times bigger than a nanometer. It is currently unclear if this contamination is affecting human health, but if the water is also found to contain nano-particle pollutants, there could be adverse impacts on human well-being, according to scientists associated with the study.[46]

However, plastic tap water pollution remains under-studied, as are the links of how pollution transfers between humans, air, water, and soil.[47]

Effects of plastic on oceans

As of 2016 it was estimated that there was approximately 150 million tonnes of plastic pollution in the world's oceans, estimated to grow to 250 million tonnes in 2025.[50] Another study estimated that in 2012, it was approximately 165 million tonnes.[21] The Ocean Conservancy reported that China, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam dump more plastic in the sea than all other countries combined.[18]

Still another scientific study based on material flow analysis estimated that there is a stock of 86 million tons of plastic marine debris in the worldwide ocean as of the end of 2013, assuming that 1.4% of global plastics produced from 1950 to 2013 has entered the ocean and has accumulated there. [51]

One study estimated that there are more than 5 trillion plastic pieces (defined into the four classes of small microplastics, large microplastics, meso- and macroplastics) afloat at sea.[49]

The litter that is being delivered into the oceans is toxic to marine life, and humans. The toxins that are components of plastic include diethylhexyl phthalate, which is a toxic carcinogen, as well as lead, cadmium, and mercury.

Plankton, fish, and ultimately the human race, through the food chain, ingest these highly toxic carcinogens and chemicals. Consuming the fish that contain these toxins can cause an increase in cancer, immune disorders, and birth defects.[52]

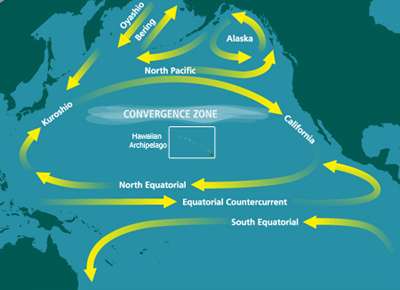

The majority of the litter near and in the ocean is made up of plastics and is a persistent pervasive source of marine pollution.[53] According to Dr. Marcus Eriksen of The 5 Gyres Institute, there are 5.25 trillion particles of plastic pollution that weigh as much as 270,000 tonnes (2016). This plastic is taken by the ocean currents and accumulates in large vortexes known as ocean gyres. The majority of the gyres become pollution dumps filled with plastic.

Sources of ocean-based plastic pollution

In October 2019, when research revealed most ocean plastic pollution comes from Chinese cargo ships,[54] an Ocean Cleanup spokesperson said: "Everyone talks about saving the oceans by stopping using plastic bags, straws and single use packaging. That's important, but when we head out on the ocean, that's not necessarily what we find."[55]

Almost 20% of plastic debris that pollutes ocean water, which translates to 5.6 million tonnes, comes from ocean-based sources. MARPOL, an international treaty, "imposes a complete ban on the at-sea disposal of plastics".[56][57] Merchant ships expel cargo, sewage, used medical equipment, and other types of waste that contain plastic into the ocean. In the United States, the Marine Plastic Pollution Research and Control Act of 1987 prohibits discharge of plastics in the sea, including from naval vessels.[58][59] Naval and research vessels eject waste and military equipment that are deemed unnecessary. Pleasure crafts release fishing gear and other types of waste, either accidentally or through negligent handling. The largest ocean-based source of plastic pollution is discarded fishing gear (including traps and nets), estimated to be up to 90% of plastic debris in some areas.[3]

Continental plastic litter enters the ocean largely through storm-water runoff, flowing into watercourses or directly discharged into coastal waters.[60] Plastic in the ocean has been shown to follow ocean currents which eventually form into what is known as Great Garbage Patches.[61] Knowledge of the routes that plastic follows in ocean currents comes from accidental container drops from ship carriers. For example, in May 1990 The Hansa Carrier, sailing from Korea to the United States, broke apart due to a storm, ultimately resulting in thousands of dumped shoes; these eventually started showing up on the U.S western coast, and Hawaii.[62]

The impact of microplastic and macroplastic into the ocean is not subjected to infiltration directly by dumping of plastic into marine ecosystems, but through polluted rivers that lead or create passageways to oceans across the globe. Rivers can either act as a source or sink depending on the context. Rivers receive and gather majority of plastic but can also prevent a good percentage from entering the ocean. Rivers are the dominant source of plastic pollution in the marine environment [63] contributing nearly 80% in recent studies.[64] The amount of plastic that is recorded to be in the ocean is considerably less than the amount of plastic that is entering the ocean at any given time. According to a study done in the UK, there are "ten top" macroplastic dominant typologies that are solely consumer related (located in the table below).[65] Within this study, 192,213 litter items were counted with an average of 71% being plastic and 59% were consumer related macroplastic items.[65] Even though freshwater pollution is the major contributor to marine plastic pollution there is little studies done and data collection for the amount of pollution going from freshwater to marine. Majority of papers conclude that there is minimal data collection of plastic debris in freshwater environments and natural terrestrial environments, even though these are the major contributor. The need for policy change in production, usage, disposal, and waste management is necessary to decrease the amount and potential of plastic to enter freshwater environments.[66]

| Present study top ten | Litter rate in the UK (Elliott and Elliott, 2018) | Litter rate ranking |

|---|---|---|

|

Variable (e.g. crisp packets 3.7%; sweet wrappers 3.1%) | 5 |

|

6.9% | 6 |

|

Unknown | - |

|

31.9% | 2 |

|

Variable (e.g. wet wipes 31.3%; Sanitary towels 21.3%) | 1 |

|

Unknown | - |

|

13.5% littered | 3 |

|

5.1% | 7 |

|

13.1% | 4 |

|

Variable (e.g. Straws 3.1%, Cutlery 0.5%; stirrers 0.2%) | 8 |

Land-based sources of ocean plastic pollution

Estimates for the contribution of land-based plastic vary widely. While one study estimated that a little over 80% of plastic debris in ocean water comes from land-based sources, responsible for 800,000 tonnes (880,000 short tons) every year.[3] In 2015, Jambeck et al. calculated that 275 million tonnes (303 million short tons) of plastic waste was generated in 192 coastal countries in 2010, with 4.8 to 12.7 million tonnes (5.3 to 14 million short tons) entering the ocean – a percentage of only up to 5%.[6]

In a study published by Science, Jambeck et al (2015) estimated that the 10 largest emitters of oceanic plastic pollution worldwide are, from the most to the least, China, Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Egypt, Malaysia, Nigeria, and Bangladesh.[6]

A source that has caused concern is landfills. Most waste in the form of plastic in landfills are single-use items such as packaging. Discarding plastics this way leads to accumulation.[15] Although disposing of plastic waste in landfills has less of a gas emission risk than disposal through incineration, the former has space limitations. Another concern is that the liners acting as protective layers between the landfill and environment can break, thus leaking toxins and contaminating the nearby soil and water.[67] Landfills located near oceans often contribute to ocean debris because content is easily swept up and transported to the sea by wind or small waterways like rivers and streams. Marine debris can also result from sewage water that has not been efficiently treated, which is eventually transported to the ocean through rivers. Plastic items that have been improperly discarded can also be carried to oceans through storm waters.[3]

Plastic pollution in the Pacific Ocean

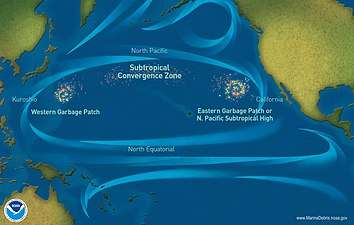

In the Pacific Gyre, specifically 20°N-40°N latitude, large bodies with floating marine debris can be found.[68] Models of wind patterns and ocean currents indicate that the plastic waste in the northern Pacific is particularly dense where the Subtropical Convergence Zone (STCZ), 23°N-37°N latitude, meets a southwest-northeast line, found north of the Hawaiian archipelago.[68]

In the Pacific, there are two mass buildups: the western garbage patch and the eastern garbage patch, the former off the coast of Japan and the latter between Hawaii and California. The two garbage patches are both part of the great Pacific garbage patch, and are connected through a section of plastic debris off the northern coast of the Hawaiian islands. It is approximated that these garbage patches contain 90 million tonnes (100 million short tons) of debris.[68] The waste is not compact, and although most of it is near the surface of the pacific, it can be found up to more than 30 metres (100 ft) deep in the water.[68]

Research published in April 2017[69] reported "the highest density of plastic rubbish anywhere in the world" on remote and uninhabited Henderson Island in South Pacific as a result of the South Pacific Gyre. The beaches contain an estimated 37.7 million items of debris together weighing 17.6 tonnes. In a study transect on North Beach, each day 17 to 268 new items washed up on a 10-metre section. The study noted that purple hermit crabs (Coenobita spinosus) make their homes in plastic containers washed up on beaches.[70][71][72]

Effects on animals

Plastic pollution has the potential to poison animals, which can then adversely affect human food supplies.[73][74] Plastic pollution has been described as being highly detrimental to large marine mammals, described in the book Introduction to Marine Biology as posing the "single greatest threat" to them.[75] Some marine species, such as sea turtles, have been found to contain large proportions of plastics in their stomach.[73] When this occurs, the animal typically starves, because the plastic blocks the animal's digestive tract.[73] Sometimes Marine mammals are entangled in plastic products such as nets, which can harm or kill them.[73]

Entanglement

Entanglement in plastic debris has been responsible for the deaths of many marine organisms, such as fish, seals, turtles, and birds. These animals get caught in the debris and end up suffocating or drowning. Because they are unable to untangle themselves, they also die from starvation or from their inability to escape predators.[3] Being entangled also often results in severe lacerations and ulcers. In a 2006 report known as Plastic Debris in the World's Oceans,[76] it was estimated that at least 267 different animal species have suffered from entanglement and ingestion of plastic debris.[5] It has been estimated that over 400,000 marine mammals perish annually due to plastic pollution in oceans.[73] Marine organisms get caught in discarded fishing equipment, such as ghost nets. Ropes and nets used to fish are often made of synthetic materials such as nylon, making fishing equipment more durable and buoyant. These organisms can also get caught in circular plastic packaging materials, and if the animal continues to grow in size, the plastic can cut into their flesh. Equipment such as nets can also drag along the seabed, causing damage to coral reefs.[77]

Ingestion

Marine animals

Sea turtles are affected by plastic pollution. Some species are consumers of jelly fish, but often mistake plastic bags for their natural prey. This plastic debris can kill the sea turtle by obstructing the oesophagus.[77] Baby sea turtles are particularly vulnerable according to a 2018 study by Australian scientists.[78]

So too are whales. Large amounts of plastics have been found in the stomachs of beached whales.[77] Plastic debris started appearing in the stomach of the sperm whale since the 1970s, and has been noted to be the cause of death of several whales.[79][80] In June 2018, more than 80 plastic bags were found inside a dying pilot whale that washed up on the shores of Thailand.[81] In March 2019, a dead Cuvier's beaked whale washed up in the Philippines with 88 lbs of plastic in its stomach.[82] In April 2019, following the discovery of a dead sperm whale off of Sardinia with 48 pounds of plastic in its stomach, the World Wildlife Foundation warned that plastic pollution is one of the most dangerous threats to sea life, noting that five whales have been killed by plastic over a two-year period.[83]

Some of the tiniest bits of plastic are being consumed by small fish, in a part of the pelagic zone in the ocean called the Mesopelagic zone, which is 200 to 1000 metres below the ocean surface, and completely dark. Not much is known about these fish, other than that there are many of them. They hide in the darkness of the ocean, avoiding predators and then swimming to the ocean's surface at night to feed.[84] Plastics found in the stomachs of these fish were collected during Malaspina's circumnavigation, a research project that studies the impact of global change on the oceans.[85]

A study conducted by Scripps Institution of Oceanography showed that the average plastic content in the stomachs of 141 mesopelagic fish over 27 different species was 9.2%. Their estimate for the ingestion rate of plastic debris by these fish in the North Pacific was between 12,000 and 24,000 tonnes per year.[86] The most popular mesopelagic fish is the lantern fish. It resides in the central ocean gyres, a large system of rotating ocean currents. Since lantern fish serve as a primary food source for the fish that consumers purchase, including tuna and swordfish, the plastics they ingest become part of the food chain. The lantern fish is one of the main bait fish in the ocean, and it eats large amounts of plastic fragments, which in turn will not make them nutritious enough for other fish to consume.[87]

Another study found bits of plastic outnumber baby fish by seven to one in nursery waters off Hawaii. After dissecting hundreds of larval fish, the researchers discovered that many fish species ingested plastic particles. Plastics were also found in flying fish, which are eaten by top predators such as tunas and most Hawaiian seabirds.[88]

Deep sea animals have been found with plastics in their stomachs.[89]

Birds

Plastic pollution does not only affect animals that live solely in oceans. Seabirds are also greatly affected. In 2004, it was estimated that gulls in the North Sea had an average of thirty pieces of plastic in their stomachs.[90] Seabirds often mistake trash floating on the ocean's surface as prey. Their food sources often has already ingested plastic debris, thus transferring the plastic from prey to predator. Ingested trash can obstruct and physically damage a bird's digestive system, reducing its digestive ability and can lead to malnutrition, starvation, and death. Toxic chemicals called polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) also become concentrated on the surface of plastics at sea and are released after seabirds eat them. These chemicals can accumulate in body tissues and have serious lethal effects on a bird's reproductive ability, immune system, and hormone balance. Floating plastic debris can produce ulcers, infections and lead to death. Marine plastic pollution can even reach birds that have never been at the sea. Parents may accidentally feed their nestlings plastic, mistaking it for food.[91] Seabird chicks are the most vulnerable to plastic ingestion since they can't vomit up their food like the adult seabirds.[92]

After the initial observation that many of the beaches in New Zealand had high concentrations of plastic pellets, further studies found that different species of prion ingest the plastic debris. Hungry prions mistook these pellets for food, and these particles were found intact within the birds' gizzards and proventriculi. Pecking marks similar to those made by northern fulmars in cuttlebones have been found in plastic debris, such as styrofoam, on the beaches on the Dutch coast, showing that this species of bird also mistake plastic debris for food.[77]

An estimate of 1.5 million Laysan albatrosses, which inhabit Midway Atoll, all have plastics in their digestive system. Midway Atoll is halfway between Asia and North America, and north of the Hawaiian archipelago. In this remote location, the plastic blockage has proven deadly to these birds. These seabirds choose red, pink, brown, and blue plastic pieces because of similarities to their natural food sources. As a result of plastic ingestion, the digestive tract can be blocked resulting in starvation. The windpipe can also be blocked, which results in suffocation.[5] The debris can also accumulate in the animal's gut, and give them a false sense of fullness which would also result in starvation. On the shore, thousands of birds corpses can be seen with plastic remaining where the stomach once was. The durability of the plastics is visible among the remains. In some instances, the plastic piles are still present while the bird's corpse has decayed.[5]

Similar to humans, animals exposed to plasticizers can experience developmental defects. Specifically, sheep have been found to have lower birth weights when prenatally exposed to bisphenol A. Exposure to BPA can shorten the distance between the eyes of a tadpole. It can also stall development in frogs and can result in a decrease in body length. In different species of fish, exposure can stall egg hatching and result in a decrease in body weight, tail length, and body length.[9]

Effects on humans

Compounds that are used in manufacturing pollute the environment by releasing chemicals into the air and water. Some compounds that are used in plastics, such as phthalates, bisphenol A (BRA), polybrominated diphenyl ether (PBDE), are under close statute and might be very hurtful. Even though these compounds are unsafe, they have been used in the manufacturing of food packaging, medical devices, flooring materials, bottles, perfumes, cosmetics and much more. The large dosage of these compounds are hazardous to humans, destroying the endocrine system. BRA imitates the female's hormone called estrogen. PBD destroys and causes damage to thyroid hormones, which are vital hormone glands that play a major role in the metabolism, growth and development of the human body. Although the level of exposure to these chemicals varies depending on age and geography, most humans experience simultaneous exposure to many of these chemicals. Average levels of daily exposure are below the levels deemed to be unsafe, but more research needs to be done on the effects of low dose exposure on humans.[93] A lot is unknown on how severely humans are physically affected by these chemicals. Some of the chemicals used in plastic production can cause dermatitis upon contact with human skin.[94] In many plastics, these toxic chemicals are only used in trace amounts, but significant testing is often required to ensure that the toxic elements are contained within the plastic by inert material or polymer.[94] Children and women during their reproduction age are at most at risk and more prone to damaging their immune as well as their reproductive system from these hormone-disrupting chemicals.

It can also affect humans because it may create an eyesore that interferes with enjoyment of the natural environment.[95]

Clinical significance

Due to the pervasiveness of plastic products, most of the human population is constantly exposed to the chemical components of plastics. 95% of adults in the United States have had detectable levels of BPA in their urine. Exposure to chemicals such as BPA have been correlated with disruptions in fertility, reproduction, sexual maturation, and other health effects.[67] Specific phthalates have also resulted in similar biological effects.

Thyroid hormone axis

Bisphenol A affects gene expression related to the thyroid hormone axis, which affects biological functions such as metabolism and development. BPA can decrease thyroid hormone receptor (TR) activity by increasing TR transcriptional corepressor activity. This then decreases the level of thyroid hormone binding proteins that bind to triiodothyronine. By affecting the thyroid hormone axis, BPA exposure can lead to hypothyroidism.[9]

Sex hormones

BPA can disrupt normal, physiological levels of sex hormones. It does this by binding to globulins that normally bind to sex hormones such as androgens and estrogens, leading to the disruption of the balance between the two. BPA can also affect the metabolism or the catabolism of sex hormones. It often acts as an antiandrogen or as an estrogen, which can cause disruptions in gonadal development and sperm production.[9]

Reduction efforts

Efforts to reduce the use of plastics and to promote plastic recycling have occurred. Some supermarkets charge their customers for plastic bags, and in some places more efficient reusable or biodegradable materials are being used in place of plastics. Some communities and businesses have put a ban on some commonly used plastic items, such as bottled water and plastic bags.[96]

In January 2019 a "Global Alliance to End Plastic Waste" was created by companies in the plastics industry. The alliance aims to clean the environment from existing waste and increase recycling, but it does not mention reduction in plastic production as one of its targets.[97]

Biodegradable and degradable plastics

The use of biodegradable plastics has many advantages and disadvantages. Biodegradables are biopolymers that degrade in industrial composters. Biodegradables do not degrade as efficiently in domestic composters, and during this slower process, methane gas may be emitted.[93]

There are also other types of degradable materials that are not considered to be biopolymers, because they are oil-based, similar to other conventional plastics. These plastics are made to be more degradable through the use of different additives, which help them degrade when exposed to UV rays or other physical stressors.[93] yet, biodegradation-promoting additives for polymers have been shown not to significantly increase biodegradation.[98]

Although biodegradable and degradable plastics have helped reduce plastic pollution, there are some drawbacks. One issue concerning both types of plastics is that they do not break down very efficiently in natural environments. There, degradable plastics that are oil-based may break down into smaller fractions, at which point they do not degrade further.[93]

A Parliamentary committee in the United Kingdom also found that compostable and biodegradable plastics could add to marine pollution because there is a lack of infrastructure to deal with these new types of plastic, as well as a lack of understanding about them on the part of consumers.[99] For example, these plastics need to be sent to industrial composting facilities to degrade properly, but no adequate system exists to make sure waste reaches these facilities.[99] The committee thus recommended to reduce the amount of plastic used rather than introducing new types of it to the market.[99]

Incineration

Up to 60% of used plastic medical equipment is incinerated rather than deposited in a landfill as a precautionary measure to lessen the transmission of disease. This has allowed for a large decrease in the amount of plastic waste that stems from medical equipment. If plastic waste is not incinerated and disposed of properly, a harmful amount of toxins can be released and dispersed as a gas through air or as ash through air and waterways.[67] Many studies have been done concerning the gaseous emissions that result from the incineration process.

Policy

Agencies such as the US Environmental Protection Agency and US Food and Drug Administration often do not assess the safety of new chemicals until after a negative side effect is shown. Once they suspect a chemical may be toxic, it is studied to determine the human reference dose, which is determined to be the lowest observable adverse effect level. During these studies, a high dose is tested to see if it causes any adverse health effects, and if it does not, lower doses are considered to be safe as well. This does not take into account the fact that with some chemicals found in plastics, such as BPA, lower doses can have a discernible effect.[100] Even with this often complex evaluation process, policies have been put into place in order to help alleviate plastic pollution and its effects. Government regulations have been implemented that ban some chemicals from being used in specific plastic products.

In Canada, the United States, and the European Union, BPA has been banned from being incorporated in the production of baby bottles and children's cups, due to health concerns and the higher vulnerability of younger children to the effects of BPA.[67] Taxes have been established in order to discourage specific ways of managing plastic waste. The landfill tax, for example, creates an incentive to choose to recycle plastics rather than contain them in landfills, by making the latter more expensive.[93] There has also been a standardization of the types of plastics that can be considered compostable.[93] The European Norm EN 13432, which was set by the European Committee for Standardization (CEN), lists the standards that plastics must meet, in terms of compostability and biodegradability, in order to officially be labeled as compostable.[93][101]

Institutional arrangements in Canada

The Canadian federal government formed a current institution that protects marine areas; this includes the mitigation of plastic pollution. In 1997, Canada adopted legislation for oceans management and passed the Oceans Act.[102] Federal governance, Regional Governance, and Aboriginal Peoples are the actors involved in the process of decision-making and implementation of the decision. The Regional Governance bodies are federal, provincial, and territorial government agencies that hold responsibilities of the marine environment. Aboriginal Peoples in Canada have treaty and non-treaty rights related to ocean activities. According to the Canadian government, they respect these rights and work with Aboriginal groups in oceans management activities.[102]

With the Oceans Act made legal, Canada made a commitment to conserve and protect the oceans. The Ocean Acts' underlying principle is sustainable development, precautionary and integrated management approach to ensure that there is a comprehensive understanding in protecting marine areas. In the integrated management approach, the Oceans Act designates federal responsibility to the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans Canada for any new and emerging ocean-related activities.[102] The Act encourages collaboration and coordination within the government that unifies interested parties. Moreover, the Oceans Act engages any Canadians who are interested in being informed of the decision-making regarding ocean environment.

In 2005, federal organizations developed the Federal Marine Protected Areas Strategy.[102] This strategy is a collaborative approach implemented by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Parks Canada, and Environment Canada to plan and manage federal marine protected areas. The federal marine protected areas work with Aboriginal groups, industries, academia, environmental groups, and NGOs to strengthen marine protected areas. The federal marine protected areas network consists of three core programs: Marine Protected Areas, Marine Wildlife Areas, and National Marine Conservation Areas.[102] The MPA is a program to be noted because it is significant in protecting ecosystems from the effects of industrial activities. The MPA guiding principles are Integrated Management, ecosystem-based management approach, Adaptive Management Approach, Precautionary Principle, and Flexible Management Approach.[102] All five guiding principles are used collectively and simultaneously to collaborate and respect legislative mandates of individual departments, to use scientific knowledge and traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) to manage human activities, to monitor and report on programs to meet conservation objectives of MPAs, to use best available information in the absence of scientific certainty, and to maintain a balance between conservation needs and sustainable development objectives.[102]

Collection

The two common forms of waste collection include curbside collection and the use of drop-off recycling centers. About 87 percent of the population in the United States (273 million people) have access to curbside and drop-off recycling centers. In curbside collection, which is available to about 63 percent of the United States population (193 million people), people place designated plastics in a special bin to be picked up by a public or private hauling company.[103] Most curbside programs collect more than one type of plastic resin, usually both PETE and HDPE.[104] At drop-off recycling centers, which are available to 68 percent of the United States population (213 million people), people take their recyclables to a centrally located facility.[103] Once collected, the plastics are delivered to a materials recovery facility (MRF) or handler for sorting into single-resin streams to increase product value. The sorted plastics are then baled to reduce shipping costs to reclaimers.[104]

There are varying rates of recycling per type of plastic, and in 2017, the overall plastic recycling rate was approximately 8.4% in the United States. Approximately 2.7 million tonnes (3.0 million short tons) of plastics were recycled in the U.S. in 2017, while 24.3 million tonnes (26.8 million short tons) plastic were dumped in landfills the same year. Some plastics are recycled more than others; in 2017 about 31.2 percent of HDPE bottles and 29.1 percent of PET bottles and jars were recycled.[105]

In 21 May 2019, a new service model called "Loop" to collect packaging from consumers and reuse it, began to function in the New York region, US. Consumers drop packages in special shipping totes and then a pick up collect them. Partners include Procter & Gamble, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Unilever, Mars Petcare, The Clorox Company, The Body Shop, Coca-Cola, Mondelēz, Danone and other firms.[106] It has begun with several thousand households, but there are 60,000 on the waiting list. The target of the service is not only stop single use plastic, but to stop single use generally by recycling consumer product containers of various materials.[107]

Non-usage and reduction in usage

European Union

In 2015 The European Union adopted a directive, that require a reduction in the consumption of single use plastic bags per person, to 90 by the year 2019 and to 40 by the year 2025.[108] In April 2019, the European Union adopted a law banning almost all types of single use plastic, except bottles, from the beginning of the year 2021.[109]

China

In 2020 China published its plan to cut 30% of plastic waste in 5 years. As part of this plan, single use plastic bags and straws will be banned[110][111]

India

The government of India decided to ban single use plastics and take a number of measures to recycle and reuse plastic, from 2 October 2019[112]

The Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Government of India, has requested various governmental departments to avoid the use of plastic bottles to provide drinking water during governmental meetings, etc., and to instead make arrangements for providing drinking water that do not generate plastic waste.[113][114] The state of Sikkim has restricted the usage of plastic water bottles (in government functions and meetings) and styrofoam products.[115] The state of Bihar has banned the usage of plastic water bottles in governmental meetings.[116]

The 2015 National Games of India, organised in Thiruvananthapuram, was associated with green protocols.[117] This was initiated by Suchitwa Mission that aimed for "zero-waste" venues. To make the event "disposable-free", there was ban on the usage of disposable water bottles.[118] The event witnessed the usage of reusable tableware and stainless steel tumblers.[119] Athletes were provided with refillable steel flasks.[120] It is estimated that these green practices stopped the generation of 120 tonnes of disposable waste.[121]

The city of Bangalore in 2016 banned the plastic for all purpose other than for few special cases like milk delivery etc.[122]

The state of Maharashtra, India effected the Maharashtra Plastic and Thermocol Products ban 23 June 2018, subjecting plastic users to fines and potential imprisonment for repeat offenders.[123][124]

Albania

In July 2018, Albania became the first country in Europe to ban lightweight plastic bags.[125][126][127] Albania's environment minister Blendi Klosi said that businesses importing, producing or trading plastic bags less than 35 microns in thickness risk facing fines between 1 million to 1.5 million lek (€7,900 to €11,800).[126]

Bali

In Bali, a pair of two sisters, Melati and Isabel Wijsen, have gone through efforts to ban plastic bags in 2019.[128][129] Their organization Bye Bye Plastic Bags has spread to 28 locations around the world.

United States of America

In 2009, Washington University in St. Louis became the first university in the United States to ban the sale of plastic, single-use water bottles.[130]

In 2009, District of Columbia required all businesses that sell food or alcohol to charge an additional 5 cents for each carryout plastic or paper bag.[131]

In 2011 and 2013, Kauai, Maui and Hawaii prohibit non-biodegradable plastic bags at checkout as well as paper bags containing less than 40 percent recycled material. In 2015, Honolulu was the last major county approving the ban.[131]

In 2015, California prohibited large stores from providing plastic bags, and if so a charge of $0.10 per bag and has to meet certain criteria.[131]

In 2016, Illinois adopted the legislation and established “Recycle Thin Film Friday” in effort toe reclaim used thin-film plastic bags and encourage reusable bags.[131]

In 2019 The New York (state) banned single use plastic bags and introduced a 5-cent fee for using single use paper bags. The ban will enter into force in 2020. This will not only reduce plastic bag usage in New York state (23,000,000,000 every year until now), but also eliminate 12 million barrels of oil used to make plastic bags used by the state each year.[132][133]

The state of Maine ban Styrofoam (polystyrene) containers in May 2019.[134]

In 2019 the Giant Eagle retailer became the first big US retailer that committed to completely phase out plastic by 2025. The first step - stop using single use plastic bags - will begun to be implemented already on January 15, 2020.[135]

In 2019, Delaware, Maine, Oregon and Vermont enacted on legislation. Vermont also restricted single-use straws and polystyrene containers.[131]

In 2019, Connecticut imposed a $0.10 charge on single-use plastic bags at point of sale, and is going to ban them on July 1, 2021.[131]

Nigeria

In 2019, The House of Representatives of Nigeria banned the production, import and usage of plastic bags in the country.[136]

Israel

In Israel, 2 cities: Eilat and Herzliya, decided to ban the usage of single use plastic bags and cutlery on the beaches.[137] In 2020 Tel Aviv joined them, banning also the sale of single use plastic on the beaches.[138]

United Kingdom

In January 2019, the Iceland supermarket chain, which specializes in frozen foods, pledged to "eliminate or drastically reduce all plastic packaging for its store-brand products by 2023."[139]

As of 2020, 104 communities achieved the title of "Plastic free community" in United Kingdom, 500 want to achieve it.[140]

After 2 schoolgirls Ella and Caitlin launched a petition about it, Burger King and McDonald's in the United Kingdom and Ireland pledged to stop sending plastic toys with their meals. McDonald's pledged to do it from the year 2021. McDonald's also pledged to use a paper wrap for it meals and books that will be sent with the meals. The transmission will begin already in March 2020.[141]

Kenya

In August 2017, Kenya has one of the world’s harshest plastic bag bans. Fines of $38,000 or up to four years in jail to anyone that was caught producing, selling, or using a plastic bag.[142]

Vanuatu

On July 30, 2017, Vanuatu’s Independence Day, made an announcement of stepping towards the beginning of not using plastic bags and bottles. Making it one of the first Pacific nations to do so and will start banning the importation of single-use plastic bottles and bags.[142]

Taiwan

In February 2018, Taiwan restricted the use if single-use plastic cups, straws, utensils and bags; the ban will also include an extra charge for plastic bags and updates their recycling regulations and aiming by 2030 it would be completely enforced.[142]

Action for creating awareness

Earth Day

In 2019, the Earth Day Network partnered with Keep America Beautiful and National Cleanup Day for the inaugural nationwide Earth Day CleanUp. Cleanups were held in all 50 states, five US territories, 5,300 sites and had more than 500,000 volunteers.[143][144]

Earth Day 2020 is the 50th Anniversary of Earth Day. Celebrations will include activities such as the Great Global CleanUp, Citizen Science, Advocacy, Education, and art. This Earth Day aims to educate and mobilize more than one billion people to grow and support the next generation of environmental activists, with a major focus on plastic waste[145][146]

World Environment Day

Every year, 5 June is observed as World Environment Day to raise awareness and increase government action on the pressing issue. In 2018, India was host to the 43rd World Environment Day and the theme was "Beat Plastic Pollution", with a focus on single-use or disposable plastic. The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change of India invited people to take care of their social responsibility and urged them to take up green good deeds in everyday life. Several states presented plans to ban plastic or drastically reduce thei use.[147]

Other actions

On 11 April 2013 in order to create awareness, artist Maria Cristina Finucci founded The Garbage Patch State at UNESCO[148] headquarters in Paris, France, in front of Director General Irina Bokova. This was the first of a series of events under the patronage of UNESCO and of the Italian Ministry of the Environment.[149]

See also

- Citizen Science, cleanup projects that people can take part in.

- Cocos (Keeling) Islands

- Diisononyl phthalate, a phthalate used as a plasticizer.

- Great Pacific garbage patch, an area of exceptionally high concentrations of pelagic plastics, chemical sludge, and other debris

- Marina DeBris (Australian artist)

- Marine pollution

- Municipal solid waste

- Microplastics

- National Cleanup Day

- Plastic-eating organisms

- Plastic particle water pollution

- Plastic Pollution Coalition

- Plastic soup

- Plasticulture

- Plastiglomerate

- Plastisphere

- Rubber pollution

- United Nations Ocean Conference

- Zero waste

Notes

- "Campaigners have identified the global trade in plastic waste as a main culprit in marine litter, because the industrialised world has for years been shipping much of its plastic “recyclables” to developing countries, which often lack the capacity to process all the material."[13]

- "The new UN rules will effectively prevent the US and EU from exporting any mixed plastic waste, as well plastics that are contaminated or unrecyclable — a move that will slash the global plastic waste trade when it comes into effect in January 2021."[13]

References

- "Plastic pollution". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- Laura Parker (June 2018). "We Depend on Plastic. Now We're Drowning in It". NationalGeographic.com. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- Hammer, J; Kraak, MH; Parsons, JR (2012). "Plastics in the marine environment: the dark side of a modern gift". Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 220: 1–44. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-3414-6_1. ISBN 978-1461434139. PMID 22610295.

- Hester, Ronald E.; Harrison, R. M. (editors) (2011). Marine Pollution and Human Health. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 84–85. ISBN 184973240X

- Le Guern, Claire (March 2018). "When The Mermaids Cry: The Great Plastic Tide". Coastal Care. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- Jambeck, Jenna R.; Geyer, Roland; Wilcox, Chris; et al. (2015). "Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean" (PDF). Science. 347 (6223): 768–71. Bibcode:2015Sci...347..768J. doi:10.1126/science.1260352. PMID 25678662. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- "The known unknowns of plastic pollution". The Economist. 3 March 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- Nomadic, Global (29 February 2016). "Turning rubbish into money – environmental innovation leads the way".

- Mathieu-Denoncourt, Justine; Wallace, Sarah J.; de Solla, Shane R.; Langlois, Valerie S. (November 2014). "Plasticizer endocrine disruption: Highlighting developmental and reproductive effects in mammals and non-mammalian aquatic species". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 219: 74–88. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.11.003. PMID 25448254.

- Walker, Tony R.; Xanthos, Dirk (2018). "A call for Canada to move toward zero plastic waste by reducing and recycling single-use plastics". Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 133: 99–100. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.02.014.

- "Picking up litter: Pointless exercise or powerful tool in the battle to beat plastic pollution?". unenvironment.org. 18 May 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Sutter, John D. (12 December 2016). "How to stop the sixth mass extinction". CNN. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Clive Cookson 2019.

- Walker, T.R.; Reid, K.; Arnould, J.P.Y.; Croxall, J.P. (1997). "Marine debris surveys at Bird Island, South Georgia 1990–1995". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 34: 61–65. doi:10.1016/S0025-326X(96)00053-7.

- Barnes, D. K. A.; Galgani, F.; Thompson, R. C.; Barlaz, M. (14 June 2009). "Accumulation and fragmentation of plastic debris in global environments". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 364 (1526): 1985–1998. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0205. PMC 2873009. PMID 19528051.

- Pettipas, Shauna; Bernier, Meagan; Walker, Tony R. (2016). "A Canadian policy framework to mitigate plastic marine pollution". Marine Policy. 68: 117–22. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2016.02.025.

- Driedger, Alexander G.J.; Dürr, Hans H.; Mitchell, Kristen; Van Cappellen, Philippe (March 2015). "Plastic debris in the Laurentian Great Lakes: A review" (PDF). Journal of Great Lakes Research. 41 (1): 9–19. doi:10.1016/j.jglr.2014.12.020.

- Hannah Leung (21 April 2018). "Five Asian Countries Dump More Plastic into Oceans Than Anyone Else Combined: How You Can Help". Forbes. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

China, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam are dumping more plastic into oceans than the rest of the world combined, according to a 2017 report by Ocean Conservancy

- Knight 2012, p. 11.

- Knight 2012, p. 13.

- Knight 2012, p. 12.

- User, Super. "Small, Smaller, Microscopic!". Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- Otaga, Y. (2009). "International Pellet Watch: Global monitoring of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in coastal waters. 1. Initial phase data on PCBs, DDTs, and HCHs" (PDF). Marine Pollution Bulletin. 58 (10): 1437–46. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.06.014. PMID 19635625.

- Chemical Society, American. "Plastics in Oceans Decompose, Release Hazardous Chemicals, Surprising New Study Says". Science Daily. Science Daily. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- Chalabi, Mona (9 November 2019). "Coca-Cola is world's biggest plastics polluter – again". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "Global Brand Audit Report 2019". Break Free From Plastic. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "Top 20 Countries Ranked by Mass of Mismanaged Plastic Waste". Earth Day.org. 4 June 2018.

- Kushboo Sheth (18 September 2019). "Countries Putting The Most Plastic Waste Into The Oceans". worldatlas.com.

- Lebreton, Laurent; Andrady, Anthony (2019). "Future scenarios of global plastic waste generation and disposal". Palgrave Communications. Nature. 5 (1). doi:10.1057/s41599-018-0212-7. ISSN 2055-1045. Lebreton2019. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

the Asian continent was in 2015 the leading generating region of plastic waste with 82 Mt, followed by Europe (31 Mt) and Northern America (29 Mt). Latin America (including the Caribbean) and Africa each produced 19 Mt of plastic waste while Oceania generated about 0.9 Mt.

- "Plastic Oceans". futureagenda.org. London.

- Cheryl Santa Maria (8 November 2017). "STUDY: 95% of plastic in the sea comes from 10 rivers". The Weather Network.

- Duncan Hooper; Rafael Cereceda (20 April 2018). "What plastic objects cause the most waste in the sea?". Euronews.

- Christian Schmidt; Tobias Krauth; Stephan Wagner (11 October 2017). "Export of Plastic Debris by Rivers into the Sea". Environmental Science & Technology. 51 (21): 12246–53. Bibcode:2017EnST...5112246S. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b02368. PMID 29019247.

The 10 top-ranked rivers transport 88–95% of the global load into the sea

- Harald Franzen (30 November 2017). "Almost all plastic in the ocean comes from just 10 rivers". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

It turns out that about 90 percent of all the plastic that reaches the world's oceans gets flushed through just 10 rivers: The Yangtze, the Indus, Yellow River, Hai River, the Nile, the Ganges, Pearl River, Amur River, the Niger, and the Mekong (in that order).

- Daphne Ewing-Chow (20 September 2019). "Caribbean Islands Are The Biggest Plastic Polluters Per Capita In The World". Forbes.

- "Sweeping New Report on Global Environmental Impact of Plastics Reveals Severe Damage to Climate". Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL). Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- Plastic & Climate: The Hidden Costs of a Plastic Planet (PDF). May 2019. Retrieved 28 May 2019.

- "An underestimated threat: Land-based pollution with microplastics". sciencedaily.com. 5 February 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Plastic planet: How tiny plastic particles are polluting our soil". unenvironment.org. 3 April 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Mismanaged plastic waste". Our World in Data. 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- McCarthy, Niall. "The Countries Polluting The Oceans The Most". statista.com. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Aggarwal,Poonam; (et al.) Interactive Environmental Education Book VIII. Pitambar Publishing. p. 86. ISBN 8120913736

- "Invisibles". orbmedia.org. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- "Synthetic Polymer Contamination in Global Drinking Water". orbmedia.org. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- "Your tap water may contain plastic, researchers warn (Update)". Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- editor, Damian Carrington Environment (5 September 2017). "Plastic fibres found in tap water around the world, study reveals". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 15 September 2017.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Lui, Kevin. "Plastic Fibers Are Found in '83% of the World's Tap Water'". Time. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- "Great Pacific Garbage Patch". Marine Debris Division – Office of Response and Restoration. NOAA. 11 July 2013. Archived from the original on 17 April 2014.

- Eriksen, Marcus (10 December 2014). "Plastic Pollution in the World's Oceans: More than 5 Trillion Plastic Pieces Weighing over 250,000 Tons Afloat at Sea". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e111913. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k1913E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111913. PMC 4262196. PMID 25494041.

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation; McKinsey & Company; World Economic Forum (2016). "The New Plastics Economy — Rethinking the future of plastics" (PDF). Ellen MacArthur Foundation. p. 29. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- {{Jang, Y. C., Lee, J., Hong, S., Choi, H. W., Shim, W. J., & Hong, S. Y. 2015. Estimating the global inflow and stock of plastic marine debris using material flow analysis: a preliminary approach. Journal of the Korean Society for Marine Environment and Energy, 18(4), 263-273.}}

- Fernandez, Esteve; Chatenoud, Liliane (1 July 1999). "Fish consumption and cancer risk". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 70 (1): 85–90. doi:10.1093/ajcn/70.1.85. PMID 10393143.

- Walker, T. R. (2018). "Drowning in debris: Solutions for a global pervasive marine pollution problem". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 126: 338. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.11.039.

- Ryan, Peter G.; Dilley, Ben J.; Ronconi, Robert A.; Connan, Maëlle (2019). "Rapid increase in Asian bottles in the South Atlantic Ocean indicates major debris inputs from ships". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (42): 20892–97. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11620892R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1909816116. PMC 6800376. PMID 31570571.

- "Multimedia". 27 February 2012.

- Muhammad Taufan (26 January 2017). "Oceans of Plastic: Fixing Indonesia's Marine Debris Pollution Laws". The Diplomat. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

MARPOL Annex V contains regulations on vessel-borne garbage and its disposal. It sets limit on what may be disposed at sea and imposes a complete ban on the at-sea disposal of plastics.

- Stephanie B. Borrelle; Chelsea M. Rochman; Max Liboiron; Alexander L. Bond; Amy Lusher; Hillary Bradshaw; and Jennifer F. Provencher (19 September 2017). "Opinion: Why we need an international agreement on marine plastic pollution". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (38): 9994–97. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.9994B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1714450114. PMC 5617320. PMID 28928233.

the 1973 Annex V of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, as modified by the Protocol of 1978 (MARPOL), is an international agreement that addresses plastic pollution. MARPOL, which bans ships from dumping plastic at sea

- Derraik, José G.B. (September 2002). "The pollution of the marine environment by plastic debris: a review". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 44 (99): 842–52. doi:10.1016/S0025-326X(02)00220-5. PMID 12405208.

In the USA, for instance, the Marine Plastics Pollution Research and Control Act of 1987 not only adopted Annex V, but also extended its application to US Navy vessels

- Craig S. Alig; Larry Koss; Tom Scarano; Fred Chitty (1990). "CONTROL OF PLASTIC WASTES ABOARD NAVAL SHIPS AT SEA" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. ProceedingsoftheSecondInternational Conference on Marine Debris, 2–7 April 1989, Honolulu, Hawaii. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

The U.S. Navy is taking a proactive approach to comply with the prohibition on the at-sea discharge of plastics mandated by the Marine Plastic Pollution Research and Control Act of 1987

- Cozar, Andres (2014). "Plastic debris in the open ocean". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (28): 10239–44. Bibcode:2014PNAS..11110239C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1314705111. PMC 4104848. PMID 24982135.

- "Great Pacific Garbage Patch". Marine debris program. NOAA. 11 July 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- "Ocean Currents". SEOS. SEOS. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- Schmidt, Christian; Krauth, Tobias; Wagner, Stephan (7 November 2017). "Export of Plastic Debris by Rivers into the Sea". Environmental Science & Technology. 51 (21): 12246–12253. Bibcode:2017EnST...5112246S. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b02368. ISSN 0013-936X. PMID 29019247.

- Schmidt, Christian; Krauth, Tobias; Wagner, Stephan (7 November 2017). "Export of Plastic Debris by Rivers into the Sea". Environmental Science & Technology. 51 (21): 12246–12253. Bibcode:2017EnST...5112246S. doi:10.1021/acs.est.7b02368. ISSN 0013-936X. PMID 29019247.

- Winton, Debbie J.; Anderson, Lucy G; Rocliffe, Stephen; Loiselle, Steven (November 2019). "Macroplastic pollution in freshwater environments: focusing public and policy action". Science of the Total Environment. 704: 135242. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135242. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 31812404.

- Segar, D. (1982). "Ocean waste disposal monitoring--Can it meet management needs?". Oceans 82. IEEE. pp. 1277–1281. doi:10.1109/oceans.1982.1151934.

- North, Emily J.; Halden, Rolf U. (1 January 2013). "Plastics and environmental health: the road ahead". Reviews on Environmental Health. 28 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1515/reveh-2012-0030. PMC 3791860. PMID 23337043.

- "Marine Debris in the North Pacific A Summary of Existing Information and Identification of Data Gaps" (PDF). United States Environmental Protection Agency. 24 July 2015.

- Lavers, Jennifer L.; Bond, Alexander L. (2017). "Exceptional and rapid accumulation of anthropogenic debris on one of the world's most remote and pristine islands". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (23): 6052–55. doi:10.1073/pnas.1619818114. PMC 5468685. PMID 28507128.

- Remote South Pacific island has highest levels of plastic rubbish in the world, Dani Cooper, ABC News Online, 16 May 2017

- Hunt, Elle (15 May 2017). "38 million pieces of plastic waste found on uninhabited South Pacific island". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- "No one lives on this remote Pacific island – but it's covered in 38 million pieces of our trash". Washington Post. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- Daniel D. Chiras (2004). Environmental Science: Creating a Sustainable Future. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 517–18. ISBN 0763735698

- Knight 2012, p. 5.

- Karleskint, George; (et al.) (2009).Introduction to Marine Biology. Cengage Learning. p. 536. ISBN 0495561975

- "Plastic Debris in the World's Oceans". Greenpeace International. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- Gregory, M. R. (14 June 2009). "Environmental implications of plastic debris in marine settings – entanglement, ingestion, smothering, hangers-on, hitch-hiking and alien invasions". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 364 (1526): 2013–25. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0265. PMC 2873013. PMID 19528053.

- Gabbatiss, Josh (13 September 2018). "Half of dead baby turtles found by Australian scientists have stomachs full of plastic". The Independent. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- Chua, Marcus A.H.; Lane, David J.W.; Ooi, Seng Keat; Tay, Serene H.X.; Kubodera, Tsunemi (5 April 2019). "Diet and mitochondrial DNA haplotype of a sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) found dead off Jurong Island, Singapore". PeerJ. 7: e6705. doi:10.7717/peerj.6705. PMC 6452849. PMID 30984481.

- de Stephanis, Renaud; Giménez, Joan; Carpinelli, Eva; Gutierrez-Exposito, Carlos; Cañadas, Ana (April 2013). "As main meal for sperm whales: Plastics debris". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 69 (1–2): 206–has 14. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2013.01.033. hdl:10261/75929. PMID 23465618.

- "Whale dies from eating more than 80 plastic bags". The Guardian. 2 June 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- "Dead Philippines whale had 40 kg of plastic in stomach". BBC. 18 March 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- Barry, Colleen (2 April 2019). "WWF Sounds Alarm After 48 Pounds of Plastic Found in Dead Whale". Truthdig. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- Parker, L. (2014). New Map Reveals Extent of Ocean Plastic. National Geographic

- Fernandez-Armesto, F. (2006). Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration

- Carson, Henry S.; Colbert, Steven L.; Kaylor, Matthew J.; McDermid, Karla J. (2011). "Small plastic debris changes water movement and heat transfer through beach sediments". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 62 (8): 1708–13. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.05.032. PMID 21700298.

- Moore, C. J. (2014) Choking the Oceans with Plastic. New York Times

- "Where plastic outnumbers fish by seven to one". BBC News. 12 November 2019.

- Taylor, Matthew (15 November 2017). "Plastics found in stomachs of deepest sea creatures". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Hill, Marquita K. (1997). Understanding Environmental Pollution. Cambridge University Press. p. 257. ISBN 1139486403

- Rodríguez, A; et al. (2012). "High prevalence of parental delivery of plastic debris in Cory's shearwaters (Calonectris diomedea)" (PDF). Marine Pollution Bulletin. 64 (10): 2219–2223. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2012.06.011. hdl:10261/56764. PMID 22784377.

- Derraik, J. G. B. (2002) The Pollution of the Marine Environment by Plastic Debris: a review

- Thompson, R. C.; Moore, C. J.; vom Saal, F. S.; Swan, S. H. (14 June 2009). "Plastics, the environment and human health: current consensus and future trends". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 364 (1526): 2153–66. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0053. PMC 2873021. PMID 19528062.

- Brydson, J. A. (1999). Plastics Materials. Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 103–04. ISBN 0750641320

- (1973). Polyvinyl Chloride Liquor Bottles: Environmental Impact Statement. United States. Department of the Treasury (contributor).

- Malkin, Bonnie (8 July 2009). "Australian town bans bottled water". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

- Staff, Waste360 (16 January 2019). "New Global Alliance to End Plastic Waste Has Launched". Waste360. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

- Selke, Susan; Auras, Rafael; Nguyen, Tuan Anh; Castro Aguirre, Edgar; Cheruvathur, Rijosh; Liu, Yan (2015). "Evaluation of Biodegradation-Promoting Additives for Plastics". Environmental Science & Technology. 49 (6): 3769–77. Bibcode:2015EnST...49.3769S. doi:10.1021/es504258u. PMID 25723056.

- "Plastic alternatives may worsen marine pollution, MPs warn". The Guardian. 12 September 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- Groff, Tricia (2010). "Bisphenol A: invisible pollution". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 22 (4): 524–29. doi:10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833b03f8. PMID 20489636.

- "EN 13432". Green Plastics.

- Government of Canada (2014). "Oceans Act: Governance for sustainable marine ecosystems". Government of Canada. Government of Canada.

- "AF&PA Releases Community Recycling Survey Results". Archived from the original on 2 June 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- "Life cycle of a plastic product". Americanchemistry.com. Archived from the original on 17 March 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2012.

- "Facts and Figures about Materials, Waste and Recycling". United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Lorraine Chow J, Lorraine (25 January 2019). "World's Biggest Brands Join Ambitious New Packaging Model". Ecowatch. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- HIRSH, SOPHIE. "'Loop' Launches in the U.S., Bringing Customers the Products They Love in a Milkman Model". Greenmatters. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Barbière, Cécile (29 April 2015). "EU to halve plastic bag use by 2019". Euroactive. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Matthews, Lyndsey (16 April 2019). "Single-Use Plastics Will Be Banned in Europe by 2021". Afar. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- "Single-use plastic: China to ban bags and other items". BBC. 20 January 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- "China to ban single-use plastic bags and straws". Deutsche Welle. 20 January 2020. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Mathew, Liz (5 September 2019). "From 2 October, Govt to crack down on single-use plastic". The Indian Express. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- "Avoiding use of bottled water" (PDF). Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "Avoiding use of bottled water" (PDF). Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "Ban on Styrofoam Products and Packaged Water Bottles". Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "Bihar bans plastic packaged water bottles". Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "Green rules of the National Games". The Hindu.

- "National Games: Green Panel Recommends Ban on Plastic". The New Indian Express.

- "Kochi a 'Museum City' Too". The New Indian Express. 8 February 2016. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- "National Games 2015: Simple Steps To Keep Games Green". yentha.com. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- "Setting a New Precedent". The New Indian Express.

- "Plastic ban in Bangalore" (PDF).

- "Plastic ban in Maharashtra: What is allowed, what is banned". TheIndianExpress. 27 June 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "Plastic Waste Management in Maharashtra". Maharashtra Pollution Control Board. 23 June 2018. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- "Rama: Albania the first country in Europe to ban plastic bags lawfully | Radio Tirana International". rti.rtsh.al. 13 June 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "Albania bans non-biodegradable plastic bags". Tirana Times. 4 July 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- "Balkans bans the bag". makeresourcescount.eu. 3 July 2017. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- Paddock, Richard C. (3 July 2020). "After Fighting Plastic in 'Paradise Lost,' Sisters Take On Climate Change". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

- "How Teenage Sisters Pushed Bali To Say 'Bye-Bye' To Plastic Bags". NPR.org. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- "Water bottle ban a success; bottled beverage sales have plummeted | The Source | Washington University in St. Louis". The Source. 20 April 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- https://www.ncsl.org/research/environment-and-natural-resources/plastic-bag-legislation.aspx

- Nace, Trevor (23 April 2019). "New York Officially Bans Plastic Bags". Forbes. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Gold, Michael (22 April 2019). "Paper or Plastic? Time to Bring Your Own Bag". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Rosane, Olivia (1 May 2019). "Maine First U.S. State to Ban Styrofoam Containers". Ecowatch. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- Rosane, Olivia (18 December 2019). "Giant Eagle Becomes First U.S. Retailer of Its Size to Set Single-Use Plastic Phaseout". Ecowatch. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Opara, George (21 May 2019). "Reps pass bill banning plastic bags, prescribe fines against offenders". Daily Post. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Ben Zikri, Almog; Rinat, Zafrir (3 June 2019). "In First for Israel, Two Seaside Cities Ban Plastic Disposables on Beaches". Haaretz. Retrieved 4 June 2019.

- Peleg, Bar (31 March 2020). "Citing Environmental Concerns, Tel Aviv Bans Disposables on Beaches". Haaretz. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- Martinko, Katherine (17 January 2018). "UK supermarket promises to go plastic-free by 2023". TreeHugger. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- Turn, Anna (2 March 2020). "Is It Really Possible To Go 'Plastic Free'? This Town Is Showing The World How". Huffington post. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- Rosane, Olivia (18 March 2020). "McDonald's UK Happy Meals Will Be Plastic Toy Free". Ecowatch. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- "16 Times Countries and Cities Have Banned Single-Use Plastics". Global Citizen. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Earth Day 2019 CleanUp

- Earth Day Network Launches Great Global Clean Up

- Earth Day 50th Anniversary Great Global CleanUp

- Plans Underway for 50th Anniversary of Earth Day

- "All You Need To Know About India's 'Beat Plastic Pollution' Movement". 13 November 2018.

- "The garbage patch territory turns into a new state". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). 22 May 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Bibliography