Polyvinyl chloride

Polyvinyl chloride (/ˌpɒlivaɪnəl ˈklɔːraɪd/;[6] colloquial: polyvinyl, vinyl;[7] abbreviated: PVC) is the world's third-most widely produced synthetic plastic polymer (after polyethylene and polypropylene[8]). About 40 million tons of PVC are produced each year.

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

poly(1-chloroethylene)[1] | |

| Other names

Polychloroethylene | |

| Identifiers | |

| Abbreviations | PVC |

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.120.191 |

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | Polyvinyl+Chloride |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| Properties | |

| (C2H3Cl)n[2] | |

| Appearance | white, brittle solid |

| Odor | odorless |

| insoluble | |

| Solubility in alcohol | insoluble |

| Solubility in tetrahydrofuran | slightly soluble |

| −10.71×10−6 (SI, 22 °C)[3] | |

| Hazards | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Threshold limit value (TLV) |

10 mg/m3 (inhalable), 3 mg/m3 (respirable) (TWA) |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits):[4] | |

PEL (Permissible) |

15 mg/m3 (inhalable), 5 mg/m3 (respirable) (TWA) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

| Elongation at break | 20–40% |

|---|---|

| Notch test | 2–5 kJ/m2 |

| Glass Transition Temperature | 82 °C (180 °F)[5] |

| Melting point | 100 °C (212 °F) to 260 °C (500 °F)[5] |

| Effective heat of combustion | 17.95 MJ/kg |

| Specific heat (c) | 0.9 kJ/(kg·K) |

| Water absorption (ASTM) | 0.04–0.4 |

| Dielectric Breakdown Voltage | 40 MV/m |

PVC comes in two basic forms: rigid (sometimes abbreviated as RPVC) and flexible. The rigid form of PVC is used in construction for pipe and in profile applications such as doors and windows. It is also used in making bottles, non-food packaging, food-covering sheets,[9] and cards (such as bank or membership cards). It can be made softer and more flexible by the addition of plasticizers, the most widely used being phthalates. In this form, it is also used in plumbing, electrical cable insulation, imitation leather, flooring, signage, phonograph records,[10] inflatable products, and many applications where it replaces rubber.[11] With cotton or linen, it is used in the production of canvas.

Pure polyvinyl chloride is a white, brittle solid. It is insoluble in alcohol but slightly soluble in tetrahydrofuran.

Discovery

PVC was accidentally synthesized in 1872 by German chemist Eugen Baumann.[12] The polymer appeared as a white solid inside a flask of vinyl chloride that had been left exposed to sunlight. In the early 20th century, the Russian chemist Ivan Ostromislensky and Fritz Klatte of the German chemical company Griesheim-Elektron both attempted to use PVC in commercial products, but difficulties in processing the rigid, sometimes brittle polymer thwarted their efforts. Waldo Semon and the B.F. Goodrich Company developed a method in 1926 to plasticize PVC by blending it with various additives. The result was a more flexible and more easily processed material that soon achieved widespread commercial use.

Production

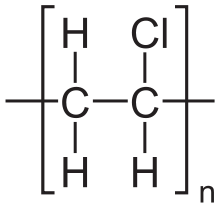

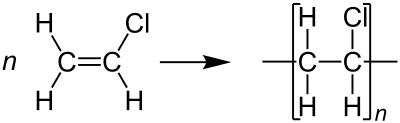

Polyvinyl chloride is produced by polymerization of the vinyl chloride monomer (VCM), as shown.[13]

About 80% of production involves suspension polymerization. Emulsion polymerization accounts for about 12%, and bulk polymerization accounts for 8%. Suspension polymerization affords particles with average diameters of 100–180 μm, whereas emulsion polymerization gives much smaller particles of average size around 0.2 μm. VCM and water are introduced into the reactor along with a polymerization initiator and other additives. The contents of the reaction vessel are pressurized and continually mixed to maintain the suspension and ensure a uniform particle size of the PVC resin. The reaction is exothermic and thus requires cooling. As the volume is reduced during the reaction (PVC is denser than VCM), water is continually added to the mixture to maintain the suspension.[8]

The polymerization of VCM is started by compounds called initiators that are mixed into the droplets. These compounds break down to start the radical chain reaction. Typical initiators include dioctanoyl peroxide and dicetyl peroxydicarbonate, both of which have fragile oxygen-oxygen bonds. Some initiators start the reaction rapidly but decay quickly, and other initiators have the opposite effect. A combination of two different initiators is often used to give a uniform rate of polymerization. After the polymer has grown by about 10 times, the short polymer precipitates inside the droplet of VCM, and polymerization continues with the precipitated, solvent-swollen particles. The weight average molecular weights of commercial polymers range from 100,000 to 200,000, and the number average molecular weights range from 45,000 to 64,000.

Once the reaction has run its course, the resulting PVC slurry is degassed and stripped to remove excess VCM, which is recycled. The polymer is then passed through a centrifuge to remove water. The slurry is further dried in a hot air bed, and the resulting powder is sieved before storage or pelletization. Normally, the resulting PVC has a VCM content of less than 1 part per million. Other production processes, such as micro-suspension polymerization and emulsion polymerization, produce PVC with smaller particle sizes (10 μm vs. 120–150 μm for suspension PVC) with slightly different properties and with somewhat different sets of applications.

PVC may be manufactured from either naphtha or ethylene feedstock.[14] However, in China, where there are substantial stocks, coal is the main starting material for the calcium carbide process. The acetylene so generated is then converted to VCM which usually involves the use of a mercury-based catalyst. The process is also very energy intensive with much waste generated.

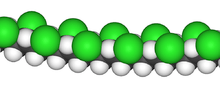

Microstructure

The polymers are linear and are strong. The monomers are mainly arranged head-to-tail, meaning that there are chlorides on alternating carbon centres. PVC has mainly an atactic stereochemistry, which means that the relative stereochemistry of the chloride centres are random. Some degree of syndiotacticity of the chain gives a few percent crystallinity that is influential on the properties of the material. About 57% of the mass of PVC is chlorine. The presence of chloride groups gives the polymer very different properties from the structurally related material polyethylene.[15] The density is also higher than these structurally related plastics.

Producers

About half of the world's PVC production capacity is in China, despite the closure of many Chinese PVC plants due to issues complying with environmental regulations and poor capacities of scale. The largest single producer of PVC as of 2018 is Shin-Etsu Chemical of Japan, with a global share of around 30%.[14] The other major suppliers are based in North America and Western Europe.

Additives

The product of the polymerization process is unmodified PVC. Before PVC can be made into finished products, it always requires conversion into a compound by the incorporation of additives (but not necessarily all of the following) such as heat stabilizers, UV stabilizers, plasticizers, processing aids, impact modifiers, thermal modifiers, fillers, flame retardants, biocides, blowing agents and smoke suppressors, and, optionally, pigments.[16] The choice of additives used for the PVC finished product is controlled by the cost performance requirements of the end use specification (underground pipe, window frames, intravenous tubing and flooring all have very different ingredients to suit their performance requirements). Previously, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were added to certain PVC products as flame retardants and stabilizers.[17]

Plasticizers

Most vinyl products contain plasticizers which are used to make the material softer and more flexible, and lower the glass transition temperature. Plasticizers work by increasing the space and act as a lubricant between the PVC polymer chains. Higher levels of plasticizer result in softer PVC compounds and decrease tensile strength.

A wide variety of substances can be used as plasticizers including phthalates, adipates, trimellitates, polymeric plasticizers and expoxidized vegetable oils. PVC compounds can be created with a very wide range of physical and chemical properties based on the types and amounts of plasticizers and other additives used. Additional selection criteria include their compatibility with the polymer, volatility levels, cost, chemical resistance, flammability and processing characteristics. These materials are usually oily colourless substances that mix well with the PVC particles. About 90% of the plasticizer market, estimated to be millions of tons per year worldwide, is dedicated to PVC.[16]

Phthalate plasticizers

The most common class of plasticizers used in PVC is phthalates, which are diesters of phthalic acid. Phthalates can be categorized as high and low, depending on their molecular weight. Low phthalates such as DEHP and DBP have increased health risks and are generally being phased out. High-molecular-weight phthalates such as DINP, DIDP and DOP are generally considered safer.

Di-2-ethylhexylphthalate

While di-2-ethylhexylphthalate (DEHP) has been medically approved for many years for use in medical devices, it was permanently banned for use in children's products in the US in 2008 by US Congress;[18] the PVC-DEHP combination had proved to be very suitable for making blood bags because DEHP stabilizes red blood cells, minimizing hemolysis (red blood cell rupture). However, DEHP is coming under increasing pressure in Europe. The assessment of potential risks related to phthalates, and in particular the use of DEHP in PVC medical devices, was subject to scientific and policy review by the European Union authorities, and on 21 March 2010, a specific labeling requirement was introduced across the EU for all devices containing phthalates that are classified as CMR (carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic to reproduction).[19] The label aims to enable healthcare professionals to use this equipment safely, and, where needed, take appropriate precautionary measures for patients at risk of over-exposure.

DEHP alternatives, which are gradually replacing it, are adipates, butyryltrihexylcitrate (BTHC), cyclohexane-1,2-dicarboxylic acid diisononylester (DINCH), di(2-ethylhexyl)terephthalate, polymerics and trimellitic acid, and 2-ethylhexylester (TOTM).

phthalate.png)

Metal stabilizers

Liquid mixed metal stabilisers are used in several PVC flexible applications such as calendered films, extruded profiles, injection moulded soles and footwear, extruded hoses and plastisols where PVC paste is spread on to a backing (flooring, wall covering, artificial leather). Liquid mixed metal stabiliser systems are primarily based on barium, zinc and calcium carboxylates. In general liquid mixed metals like BaZn and CaZn require the addition of co-stabilisers, antioxidants and organophosphites to provide optimum performance.

BaZn stabilisers have successfully replaced cadmium-based stabilisers in Europe in many PVC semi-rigid and flexible applications.[20]

In Europe, particularly Belgium, there has been a commitment to eliminate the use of cadmium (previously used as a part component of heat stabilizers in window profiles) and phase out lead-based heat stabilizers (as used in pipe and profile areas) such as liquid autodiachromate and calcium polyhydrocummate by 2015. According to the final report of Vinyl 2010,[21] cadmium was eliminated across Europe by 2007. The progressive substitution of lead-based stabilizers is also confirmed in the same document showing a reduction of 75% since 2000 and ongoing. This is confirmed by the corresponding growth in calcium-based stabilizers, used as an alternative to lead-based stabilizers, more and more, also outside Europe.

Tin-based stabilizers are mainly used in Europe for rigid, transparent applications due to the high temperature processing conditions used. The situation in North America is different where tin systems are used for almost all rigid PVC applications. Tin stabilizers can be divided into two main groups, the first group containing those with tin-oxygen bonds and the second group with tin-sulfur bonds.

Heat stabilizers

One of the most crucial additives are heat stabilizers. These agents minimize loss of HCl, a degradation process that starts above 70 °C (158 °F). Once dehydrochlorination starts, it is autocatalytic. Many diverse agents have been used including, traditionally, derivatives of heavy metals (lead, cadmium). Metallic soaps (metal "salts" of fatty acids) are common in flexible PVC applications, species such as calcium stearate.[8] Addition levels vary typically from 2% to 4%. Tin mercaptides are widely used globally in rigid PVC applications due to their high efficiency and proven performance. Typical usage levels are 0.3 (pipe) to 2.5 phr (foam) depending on the application. Tin stabilizers are the preferred stabilizers for high output PVC and CPVC extrusion. Tin stabilizers have been in use for over 50 years by companies such as PMC organometallix and its predecessors. The choice of the best PVC stabilizer depends on its cost effectiveness in the end use application, performance specification requirements, processing technology and regulatory approvals.

Properties

PVC is a thermoplastic polymer. Its properties are usually categorized based on rigid and flexible PVCs.

| Property | Unit of measurement | Rigid PVC | Flexible PVC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Density[22] | g/cm3 | 1.3–1.45 | 1.1–1.35 |

| Thermal conductivity[23] | W/(m·K) | 0.14–0.28 | 0.14–0.17 |

| Yield strength[22] | psi | 4,500–8,700 | 31–60 |

| MPa | 1,450–3,600 | 10.0–24.8 | |

| Young's modulus[24] | psi | 490,000 | — |

| GPa | 3.4 | — | |

| Flexural strength (yield)[24] | psi | 10,500 | — |

| MPa | 72 | — | |

| Compression strength[24] | psi | 9,500 | — |

| MPa | 66 | — | |

| Coefficient of thermal expansion (linear)[24] | mm/(mm °C) | 5×10−5 | — |

| Vicat B[23] | °C | 65–100 | Not recommended |

| Resistivity[25][26] | Ω m | 1016 | 1012–1015 |

| Surface resistivity[25][26] | Ω | 1013–1014 | 1011–1012 |

Mechanical

PVC has high hardness and mechanical properties. The mechanical properties enhance with the molecular weight increasing but decrease with the temperature increasing. The mechanical properties of rigid PVC (uPVC) are very good; the elastic modulus can reach 1500–3,000 MPa. The soft PVC (flexible PVC) elastic limit is 1.5–15 MPa.

Thermal and fire

The heat stability of raw PVC is very poor, so the addition of a heat stabilizer during the process is necessary in order to ensure the product's properties. Traditional product PVC has a maximum operating temperature around 140 °F (60 °C) when heat distortion begins to occur.[27] Melting temperatures range from 212 °F (100 °C) to 500 °F (260 °C) depending upon manufacture additives to the PVC. The linear expansion coefficient of rigid PVC is small and has good flame retardancy, the limiting oxygen index (LOI) being up to 45 or more. The LOI is the minimum concentration of oxygen, expressed as a percentage, that will support combustion of a polymer and noting that air has 20% content of oxygen.

As a thermoplastic, PVC has an inherent insulation that aids in reducing condensation formation and resisting internal temperature changes for hot and cold liquids.[27]

Electrical

PVC is a polymer with good insulation properties, but because of its higher polar nature the electrical insulating property is inferior to non-polar polymers such as polyethylene and polypropylene.

Since the dielectric constant, dielectric loss tangent value, and volume resistivity are high, the corona resistance is not very good, and it is generally suitable for medium or low voltage and low frequency insulation materials.

Chemical

PVC is chemically resistant to acids, salts, bases, fats, and alcohols, making it resistant to the corrosive effects of sewage, which is why it is so extensively utilized in sewer piping systems. It is also resistant to some solvents, this, however, is reserved mainly for uPVC (unplasticized PVC). Plasticized PVC, also known as PVC-P, is in some cases less resistant to solvents. For example, PVC is resistant to fuel and some paint thinners. Some solvents may only swell it or deform it but not dissolve it, but some, like tetrahydrofuran or acetone, may damage it.

Applications

.jpg)

Pipes

Roughly half of the world's PVC resin manufactured annually is used for producing pipes for municipal and industrial applications.[28] In the private homeowner market, it accounts for 66% of the household market in the US, and in household sanitary sewer pipe applications, it accounts for 75%.[29][30] Buried PVC pipes in both water and sanitary sewer applications that are 100 mm (4 in) in diameter and larger are typically joined by means of a gasket-sealed joint. The most common type of gasket utilized in North America is a metal reinforced elastomer, commonly referred to as a Rieber sealing system.[31] Its lightweight, low cost, and low maintenance make it attractive. However, it must be carefully installed and bedded to ensure longitudinal cracking and overbelling does not occur. Additionally, PVC pipes can be fused together using various solvent cements, or heat-fused (butt-fusion process, similar to joining high-density polyethylene (HDPE) pipe), creating permanent joints that are virtually impervious to leakage.

In February 2007 the California Building Standards Code was updated to approve the use of chlorinated polyvinyl chloride (CPVC) pipe for use in residential water supply piping systems. CPVC has been a nationally accepted material in the US since 1982; California, however, has permitted only limited use since 2001. The Department of Housing and Community Development prepared and certified an environmental impact statement resulting in a recommendation that the commission adopt and approve the use of CPVC. The commission's vote was unanimous, and CPVC has been placed in the 2007 California Plumbing Code.

Electric cables

PVC is commonly used as the insulation on electrical cables such as teck; PVC used for this purpose needs to be plasticized. Flexible PVC coated wire and cable for electrical use has traditionally been stabilised with lead, but these are being replaced with calcium-zinc based systems.

In a fire, PVC-coated wires can form hydrogen chloride fumes; the chlorine serves to scavenge free radicals and is the source of the material's fire retardancy. While hydrogen chloride fumes can also pose a health hazard in their own right, it dissolves in moisture and breaks down onto surfaces, particularly in areas where the air is cool enough to breathe, and is not available for inhalation.[32] Frequently in applications where smoke is a major hazard (notably in tunnels and communal areas), PVC-free cable insulation is preferred, such as low smoke zero halogen (LSZH) insulation.

Construction

PVC is a common, strong but lightweight plastic used in construction. It is made softer and more flexible by the addition of plasticizers. If no plasticizers are added, it is known as uPVC (unplasticized polyvinyl chloride) or rigid PVC.

uPVC is extensively used in the building industry as a low-maintenance material, particularly in Ireland, the United Kingdom, in the United States and Canada. In the US and Canada it is known as vinyl or vinyl siding.[33] The material comes in a range of colors and finishes, including a photo-effect wood finish, and is used as a substitute for painted wood, mostly for window frames and sills when installing insulated glazing in new buildings; or to replace older single-glazed windows, as it does not decompose and is weather-resistant. Other uses include fascia, and siding or weatherboarding. This material has almost entirely replaced the use of cast iron for plumbing and drainage, being used for waste pipes, drainpipes, gutters and downspouts. uPVC is known as having strong resistance against chemicals, sunlight, and oxidation from water.[34]

Signs

Polyvinyl chloride is formed in flat sheets in a variety of thicknesses and colors. As flat sheets, PVC is often expanded to create voids in the interior of the material, providing additional thickness without additional weight and minimal extra cost (see closed-cell PVC foamboard). Sheets are cut using saws and rotary cutting equipment. Plasticized PVC is also used to produce thin, colored, or clear, adhesive-backed films referred to simply as vinyl. These films are typically cut on a computer-controlled plotter (see vinyl cutter) or printed in a wide-format printer. These sheets and films are used to produce a wide variety of commercial signage products, including car body stripes and stickers.

Clothing

PVC fabric is water-resistant, used for its weather-resistant qualities in coats, skiing equipment, shoes, jackets, aprons, and sports bags.

PVC fabric has a niche role in speciality clothing, either to create an artificial leather material or at times simply for its effect. PVC clothing is common in Goth, Punk, clothing fetish and alternative fashions. PVC is less expensive than rubber, leather or latex, which it is used to simulate.

Healthcare

The two main application areas for single-use medically approved PVC compounds are flexible containers and tubing: containers used for blood and blood components, for urine collection or for ostomy products and tubing used for blood taking and blood giving sets, catheters, heart-lung bypass sets, hemodialysis sets etc. In Europe the consumption of PVC for medical devices is approximately 85,000 tons each year. Almost one third of plastic-based medical devices are made from PVC.[35] The reasons for using flexible PVC in these applications for over 50 years are numerous and based on cost effectiveness linked to transparency, light weight, softness, tear strength, kink resistance, suitability for sterilization and biocompatibility.

Flooring

Flexible PVC flooring is inexpensive and used in a variety of buildings, including homes, hospitals, offices, and schools. Complex and 3D designs are possible, which are then protected by a clear wear layer. A middle vinyl foam layer also gives a comfortable and safe feel. The smooth, tough surface of the upper wear layer prevents the buildup of dirt, which prevents microbes from breeding in areas that need to be kept sterile, such as hospitals and clinics.

Wire rope

PVC may be extruded under pressure to encase wire rope and aircraft cable used for general purpose applications. PVC coated wire rope is easier to handle, resists corrosion and abrasion, and may be color-coded for increased visibility. It is found in a variety of industries and environments both indoor and out.[36]

PVC has been used for a host of consumer products. One of its earliest mass-market consumer applications was vinyl record production. More recent examples include wallcovering, greenhouses, home playgrounds, foam and other toys, custom truck toppers (tarpaulins), ceiling tiles and other kinds of interior cladding.

PVC piping is cheaper than metals used in musical instrument making; it is therefore a common alternative when making instruments, often for leisure or for rarer instruments such as the contrabass flute.[37]

Chlorinated PVC

PVC can be usefully modified by chlorination, which increases its chlorine content to or above 67%. Chlorinated polyvinyl chloride, (CPVC), as it is called, is produced by chlorination of aqueous solution of suspension PVC particles followed by exposure to UV light which initiates the free-radical chlorination.[8] The reaction produces CPVC, which can be used in hotter and more corrosive environments than PVC.

Health and safety

Degradation

Degradation during service life, or after careless disposal, is a chemical change that drastically reduces the average molecular weight of the polyvinyl chloride polymer. Since the mechanical integrity of a plastic depends on its high average molecular weight, wear and tear inevitably weakens the material. Weathering degradation of plastics results in their surface embrittlement and microcracking, yielding microparticles that continue on in the environment. Also known as microplastics, these particles act like sponges and soak up persistent organic pollutants (POPs) around them. Thus laden with high levels of POPs, the microparticles are often ingested by organisms in the biosphere.

However there is evidence that three of the polymers (HDPE, LDPE, and PP) consistently soaked up POPs at concentrations an order of magnitude higher than did the remaining two (PVC and PET). After 12 months of exposure, for example, there was a 34-fold difference in average total POPs amassed on LDPE compared to PET at one location. At another site, average total POPs adhered to HDPE was nearly 30 times that of PVC. The researchers think that differences in the size and shape of the polymer molecules can explain why some accumulate more pollutants than others.[38] The fungus Aspergillus fumigatus effectively degrades plasticized PVC.[39] Phanerochaete chrysosporium was grown on PVC in a mineral salt agar.[40] Phanerochaete chrysosporium, Lentinus tigrinus, Aspergillus niger, and Aspergillus sydowii can effectively degrade PVC.[41]

Plasticizers

Phthalates, which are incorporated into plastics as plasticizers, comprise approximately 70% of the US plasticizer market; phthalates are by design not covalently bound to the polymer matrix, which makes them highly susceptible to leaching. Phthalates are contained in plastics at high percentages. For example, they can contribute up to 40% by weight to intravenous medical bags and up to 80% by weight in medical tubing.[42] Vinyl products are pervasive—including toys,[43] car interiors, shower curtains, and flooring—and initially release chemical gases into the air. Some studies indicate that this outgassing of additives may contribute to health complications, and have resulted in a call for banning the use of DEHP on shower curtains, among other uses.[44] Japanese car companies Toyota, Nissan, and Honda eliminated the use of PVC in car interiors since 2007.

In 2004 a joint Swedish-Danish research team found a statistical association between allergies in children and indoor air levels of DEHP and BBzP (butyl benzyl phthalate), which is used in vinyl flooring.[45] In December 2006, the European Chemicals Bureau of the European Commission released a final draft risk assessment of BBzP which found "no concern" for consumer exposure including exposure to children.[46]

EU decisions on phthalates

Risk assessments have led to the classification of low molecular weight and labeling as Category 1B Reproductive agents. Three of these phthalates, DBP, BBP and DEHP were included on annex XIV of the REACH regulation in February 2011 and will be phased out by the EU by February 2015 unless an application for authorisation is made before July 2013 and an authorisation granted. DIBP is still on the REACH Candidate List for Authorisation. Environmental Science & Technology, a peer-reviewed journal published by the American Chemical Society states that it is completely safe.[47]

In 2008 the European Union's Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks (SCENIHR) reviewed the safety of DEHP in medical devices. The SCENIHR report states that certain medical procedures used in high risk patients result in a significant exposure to DEHP and concludes there is still a reason for having some concerns about the exposure of prematurely born male babies to medical devices containing DEHP.[48] The Committee said there are some alternative plasticizers available for which there is sufficient toxicological data to indicate a lower hazard compared to DEHP but added that the functionality of these plasticizers should be assessed before they can be used as an alternative for DEHP in PVC medical devices. Risk assessment results have shown positive results regarding the safe use of High Molecular Weight Phthalates. They have all been registered for REACH and do not require any classification for health and environmental effects, nor are they on the Candidate List for Authorisation. High phthalates are not CMR (carcinogenic, mutagenic or toxic for reproduction), neither are they considered endocrine disruptors.

In the EU Risk Assessment the European Commission has confirmed that di-isononyl phthalate (DINP) and di-isodecyl phthalate (DIDP) pose no risk to either human health or the environment from any current use. The European Commission's findings (published in the EU Official Journal on 13 April 2006)[49] confirm the outcome of a risk assessment involving more than 10 years of extensive scientific evaluation by EU regulators. Following the recent adoption of EU legislation with the regard to the marketing and use of DINP in toys and childcare articles, the risk assessment conclusions clearly state that there is no need for any further measures to regulate the use of DINP. In Europe and in some other parts of the world, the use of DINP in toys and childcare items has been restricted as a precautionary measure. In Europe, for example, DINP can no longer be used in toys and childcare items that can be put in the mouth even though the EU scientific risk assessment concluded that its use in toys does not pose a risk to human health or the environment. The rigorous EU risk assessments, which include a high degree of conservatism and built-in safety factors, have been carried out under the strict supervision of the European Commission and provide a clear scientific evaluation on which to judge whether or not a particular substance can be safely used.

The FDA Paper titled "Safety Assessment of Di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) Released from PVC Medical Devices" states that critically ill or injured patients may be at increased risk of developing adverse health effects from DEHP, not only by virtue of increased exposure relative to the general population, but also because of the physiological and pharmacodynamic changes that occur in these patients compared to healthy individuals.[50]

Lead

Lead had previously been frequently added to PVC to improve workability and stability. Lead has been shown to leach into drinking water from PVC pipes.[51]

In Europe the use of lead-based stabilizers was gradually replaced. The VinylPlus voluntary commitment which began in 2000, saw European Stabiliser Producers Association (ESPA) members complete the replacement of Pb-based stabilisers in 2015.[52][53]

Vinyl chloride monomer

In the early 1970s, the carcinogenicity of vinyl chloride (usually called vinyl chloride monomer or VCM) was linked to cancers in workers in the polyvinyl chloride industry. Specifically workers in polymerization section of a B.F. Goodrich plant near Louisville, Kentucky, were diagnosed with liver angiosarcoma also known as hemangiosarcoma, a rare disease.[54] Since that time, studies of PVC workers in Australia, Italy, Germany, and the UK have all associated certain types of occupational cancers with exposure to vinyl chloride, and it has become accepted that VCM is a carcinogen.[8] Technology for removal of VCM from products has become stringent, commensurate with the associated regulations.

Dioxins

PVC produces HCl upon combustion almost quantitatively related to its chlorine content. Extensive studies in Europe indicate that the chlorine found in emitted dioxins is not derived from HCl in the flue gases. Instead, most dioxins arise in the condensed solid phase by the reaction of inorganic chlorides with graphitic structures in char-containing ash particles. Copper acts as a catalyst for these reactions.[55]

Studies of household waste burning indicate consistent increases in dioxin generation with increasing PVC concentrations.[56] According to the EPA dioxin inventory, landfill fires are likely to represent an even larger source of dioxin to the environment. A survey of international studies consistently identifies high dioxin concentrations in areas affected by open waste burning and a study that looked at the homologue pattern found the sample with the highest dioxin concentration was "typical for the pyrolysis of PVC". Other EU studies indicate that PVC likely "accounts for the overwhelming majority of chlorine that is available for dioxin formation during landfill fires."[56]

The next largest sources of dioxin in the EPA inventory are medical and municipal waste incinerators.[57] Various studies have been conducted that reach contradictory results. For instance a study of commercial-scale incinerators showed no relationship between the PVC content of the waste and dioxin emissions.[58][59] Other studies have shown a clear correlation between dioxin formation and chloride content and indicate that PVC is a significant contributor to the formation of both dioxin and PCB in incinerators.[60][61][62]

In February 2007, the Technical and Scientific Advisory Committee of the US Green Building Council (USGBC) released its report on a PVC avoidance related materials credit for the LEED Green Building Rating system. The report concludes that "no single material shows up as the best across all the human health and environmental impact categories, nor as the worst" but that the "risk of dioxin emissions puts PVC consistently among the worst materials for human health impacts."[63]

In Europe the overwhelming importance of combustion conditions on dioxin formation has been established by numerous researchers. The single most important factor in forming dioxin-like compounds is the temperature of the combustion gases. Oxygen concentration also plays a major role on dioxin formation, but not the chlorine content.[64]

The design of modern incinerators minimises PCDD/F formation by optimising the stability of the thermal process. To comply with the EU emission limit of 0.1 ng I-TEQ/m3 modern incinerators operate in conditions minimising dioxin formation and are equipped with pollution control devices which catch the low amounts produced. Recent information is showing for example that dioxin levels in populations near incinerators in Lisbon and Madeira have not risen since the plants began operating in 1999 and 2002 respectively.

Several studies have also shown that removing PVC from waste would not significantly reduce the quantity of dioxins emitted. The EU Commission published in July 2000 a Green Paper on the Environmental Issues of PVC"[65] The Commission states (on page 27) that it has been suggested that the reduction of the chlorine content in the waste can contribute to the reduction of dioxin formation, even though the actual mechanism is not fully understood. The influence on the reduction is also expected to be a second or third order relationship. It is most likely that the main incineration parameters, such as the temperature and the oxygen concentration, have a major influence on the dioxin formation". The Green Paper states further that at the current levels of chlorine in municipal waste, there does not seem to be a direct quantitative relationship between chlorine content and dioxin formation.

A study commissioned by the European Commission on "Life Cycle Assessment of PVC and of principal competing materials" states that "Recent studies show that the presence of PVC has no significant effect on the amount of dioxins released through incineration of plastic waste."[66]

End-of-life

The European waste hierarchy refers to the five steps included in the article 4 of the Waste Framework Directive:[67]

- Prevention: preventing and reducing waste generation.

- Reuse and preparation for reuse: giving the products a second life before they become waste.

- Recycle: any recovery operation by which waste materials are reprocessed into products, materials or substances whether for the original or other purposes. It includes composting and it does not include incineration.

- Recovery: some waste incineration based on a political non-scientific formula[68] that upgrades the less inefficient incinerators.

- Disposal: processes to dispose of waste be it landfilling, incineration, pyrolysis, gasification and other finalist solutions. Landfill is restricted in some EU-countries through Landfill Directives and there is a debate about incineration. For example, original plastic which contains a lot of energy is just recovered in energy instead of being recycled. According to the Waste Framework Directive, the European Waste Hierarchy is legally binding except in cases that may require specific waste streams to depart from the hierarchy. This should be justified on the basis of life-cycle thinking.

The European Commission has set new rules to promote the recovery of PVC waste for use in a number of construction products. It says: "The use of recovered PVC should be encouraged in the manufacture of certain construction products because it allows the reuse of old PVC ... This avoids PVC being discarded in landfills or incinerated causing release of carbon dioxide and cadmium in the environment".

Industry initiatives

In Europe, developments in PVC waste management have been monitored by Vinyl 2010,[69] established in 2000. Vinyl 2010's objective was to recycle 200,000 tonnes of post-consumer PVC waste per year in Europe by the end of 2010, excluding waste streams already subject to other or more specific legislation (such as the European Directives on End-of-Life Vehicles, Packaging and Waste Electric and Electronic Equipment).

Since June 2011, it is followed by VinylPlus, a new set of targets for sustainable development.[70] Its main target is to recycle 800,000 tonnes per year of PVC by 2020 including 100,000 tonnes of "difficult to recycle" waste. One facilitator for collection and recycling of PVC waste is Recovinyl.[71] The reported and audited mechanically recycled PVC tonnage in 2016 was 568,695 tonnes which in 2018 had increased to 739,525 tonnes.[72]

One approach to address the problem of waste PVC is also through the process called Vinyloop. It is a mechanical recycling process using a solvent to separate PVC from other materials. This solvent turns in a closed loop process in which the solvent is recycled. Recycled PVC is used in place of virgin PVC in various applications: coatings for swimming pools, shoe soles, hoses, diaphragms tunnel, coated fabrics, PVC sheets.[73] This recycled PVC's primary energy demand is 46 percent lower than conventional produced PVC. So the use of recycled material leads to a significant better ecological footprint. The global warming potential is 39 percent lower.[74]

Restrictions

In November 2005 one of the largest hospital networks in the US, Catholic Healthcare West, signed a contract with B. Braun Melsungen for vinyl-free intravenous bags and tubing.[75]

In January 2012 a major US West Coast healthcare provider, Kaiser Permanente, announced that it will no longer buy intravenous (IV) medical equipment made with PVC and DEHP-type plasticizers.[76]

In 1998, the US Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) arrived at a voluntary agreement with manufacturers to remove phthalates from PVC rattles, teethers, baby bottle nipples and pacifiers.[77]

Vinyl gloves in medicine

Plasticized PVC is a common material for medical gloves. Due to vinyl gloves having less flexibility and elasticity, several guidelines recommend either latex or nitrile gloves for clinical care and procedures that require manual dexterity and/or that involve patient contact for more than a brief period.[78] Vinyl gloves show poor resistance to many chemicals, including glutaraldehyde-based products and alcohols used in formulation of disinfectants for swabbing down work surfaces or in hand rubs.[78] The additives in PVC are also known to cause skin reactions such as allergic contact dermatitis. These are for example the antioxidant bisphenol A, the biocide benzisothiazolinone, propylene glycol/adipate polyester and ethylhexylmaleate.[78]

Sustainability

PVC is made from fossil fuels, including natural gas. The production process also uses sodium chloride. Recycled PVC is broken down into small chips, impurities removed, and the product refined to make pure PVC. It can be recycled roughly seven times and has a lifespan of around 140 years.

In the UK, approximately 400 tonnes of PVC are recycled every month. Property owners can recycle it through nationwide collection depots. The Olympic Delivery Authority (ODA), for example, after initially rejecting PVC as material for different temporary venues of the London Olympics 2012, has reviewed its decision and developed a policy for its use.[79] This policy highlighted that the functional properties of PVC make it the most appropriate material in certain circumstances while taking into consideration the environmental and social impacts across the whole life cycle, e.g. the rate for recycling or reuse and the percentage of recycled content. Temporary parts, like roofing covers of the Olympic Stadium, the Water Polo Arena, and the Royal Artillery Barracks, would be deconstructed and a part recycled in the VinyLoop process.[80][81]

See also

- Chloropolymers

- Plastic pressure pipe systems

- Plastic recycling

- Polyethylene

- Polypropylene

- Polymer clay

- Polyvinyl fluoride

- Polyvinylidene chloride

- Polyvinylidene fluoride

- PVC clothing

- PVC decking

- PVC fetishism

- Vinyl roof membrane

References

- "poly(vinyl chloride) (CHEBI:53243)". CHEBI. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- "Substance Details CAS Registry Number: 9002-86-2". Commonchemistry. CAS. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- Wapler, M. C.; Leupold, J.; Dragonu, I.; von Elverfeldt, D.; Zaitsev, M.; Wallrabe, U. (2014). "Magnetic properties of materials for MR engineering, micro-MR and beyond". JMR. 242: 233–242. arXiv:1403.4760. Bibcode:2014JMagR.242..233W. doi:10.1016/j.jmr.2014.02.005. PMID 24705364.

- https://www.qubicaamf.com/msds-forms/forms/gutter-coverboard-capping-en.pdf

- Wilkes, Charles E.; Summers, James W.; Daniels, Charles Anthony; Berard, Mark T. (2005). PVC Handbook. Hanser Verlag. p. 414. ISBN 978-1-56990-379-7.

- "polyvinyl chloride noun – Pronunciation – Oxford Advanced American Dictionary at Oxford Learner's Dictionaries". www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com.

- What is PVC Archived 18 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine- Retrieved 11 July 2017

- Allsopp, M. W.; Vianello, G. (2012). "Poly(Vinyl Chloride)". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a21_717.

- https://web.archive.org/save/http://www.ift.org/knowledge-center/read-ift-publications/science-reports/scientific-status-summaries/food-packaging.aspx

- Barton, F.C. (1932 [1931]). Victrolac Motion Picture Records. Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, April 1932 18(4):452–460 (accessed at archive.org on 5 August 2011)

- W. V. Titow (31 December 1984). PVC technology. Springer. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-0-85334-249-6. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- Baumann, E. (1872) "Ueber einige Vinylverbindungen" (On some vinyl compounds), Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie, 163 : 308–322.

- Chanda, Manas; Roy, Salil K. (2006). Plastics technology handbook. CRC Press. pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-0-8493-7039-7.

- "Shin-Etsu Chemical to build $1.4bn polyvinyl chloride plant in US". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- Handbook of Plastics, Elastomers, and Composites, Fourth Edition, 2002 by The McGraw-Hill, Charles A. Harper Editor-in-Chief. ISBN 0-07-138476-6

- David F. Cadogan and Christopher J. Howick "Plasticizers" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2000, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi: 10.1002/14356007.a20_439

- Karlen, Kaley. "Health Concerns and Environmental Issues with PVC-Containing Building Materials in Green Buildings" (PDF). Integrated Waste Management Board. California Environmental Protection Agency, USA. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- https://noharm-uscanada.org/issues/us-canada/phthalates-and-dehp

- Opinion on The safety of medical devices containing DEHP plasticized PVC or other plasticizers on neonates and other groups possibly at risk (2015 update). Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly-Identified Health Risks (25 June 2015).

- Liquid stabilisers. Seuropean Stabiliser Producers Association

- Vinyl 2010. The European PVC Industry's Sustainable Development Programme

- Titow 1984, p. 1186.

- Titow 1984, p. 1191.

- Titow 1984, p. 857.

- At 60% relative humidity and room temperature.

- Titow 1984, p. 1194.

- Michael A. Joyce, Michael D. Joyce (2004). Residential Construction Academy: Plumbing. Cengage Learning. pp. 63–64.

- Rahman, Shah (19–20 June 2007). PVC Pipe & Fittings: Underground Solutions for Water and Sewer Systems in North America (PDF). 2nd Brazilian PVC Congress, Sao Paulo, Brazil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2009.

- Uses for vinyl: pipe. vinylbydesign.com

- Rahman, Shah (October 2004). "Thermoplastics at Work: A Comprehensive Review of Municipal PVC Piping Products" (PDF). Underground Construction: 56–61.

- Shah Rahman (April 2007). "Sealing Our Buried Lifelines" (PDF). American Water Works Association (AWWA) OPFLOW Magazine: 12–17.

- Galloway F.M., Hirschler, M. M., Smith, G. F. (1992). "Surface parameters from small-scale experiments used for measuring HCl transport and decay in fire atmospheres". Fire Mater. 15 (4): 181–189. doi:10.1002/fam.810150405.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- PolyVinyl (Poly Vinyl Chloride) in Construction. Azom.com (26 October 2001). Retrieved on 6 October 2011.

- Strong, A. Brent (2005) Plastics: Materials and Processing. Prentice Hall. pp. 36–37, 68–72. ISBN 0131145584.

- PVC Healthcare Applications. pvcmed.org

- "Coated Aircraft Cable & Wire Rope | Lexco Cable". www.lexcocable.com. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- Building a PVC Instrument. natetrue.com

- Plastic Debris Delivers Triple Toxic Whammy, Ocean Study Shows – Algalita | Marine Research and EducationAlgalita | Marine Research and Education Archived 7 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Algalita. Retrieved on 28 January 2016.

- Ishtiaq Ali, Muhammad (2011). Microbial degradation of polyvinyl chloride plastics (PDF) (PhD). Quaid-i-Azam University. pp. 45–46. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2016.

- Ishtiaq Ali, Muhammad (2011). Microbial degradation of polyvinyl chloride plastics (PDF) (PhD). Quaid-i-Azam University. p. 76.

- Ishtiaq Ali, Muhammad (2011). Microbial degradation of polyvinyl chloride plastics (PDF) (PhD). Quaid-i-Azam University. p. 122.

- Halden, Rolf U. (2010). "Plastics and Health Risks". Annual Review of Public Health. 31: 179–194. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103714. PMID 20070188.

- Directive 2005/84/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council 14 December 2005. Official Journal of the European Union. 27 December 2005

- Vinyl shower curtains a 'volatile' hazard, study says. Canada.com (12 June 2008). Retrieved on 6 October 2011.

- Bornehag, Carl-Gustaf; Sundell, Jan; Weschler, Charles J.; Sigsgaard, Torben; Lundgren, Björn; Hasselgren, Mikael; Hägerhed-Engman, Linda; et al. (2004). "The Association between Asthma and Allergic Symptoms in Children and Phthalates in House Dust: A Nested Case–Control Study". Environmental Health Perspectives. 112 (14): 1393–1397. doi:10.1289/ehp.7187. PMC 1247566. PMID 15471731.

- Phthalate Information Center Blog: More good news from Europe. phthalates.org (3 January 2007)

- Yu, Byong Yong; Chung, Jae Woo; Kwak, Seung-Yeop (2008). "Reduced Migration from Flexible Poly(vinyl chloride) of a Plasticizer Containing β-Cyclodextrin Derivative". Environmental Science & Technology. 42 (19): 7522–7. Bibcode:2008EnST...42.7522Y. doi:10.1021/es800895x. PMID 18939596.

- Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks. (PDF) . Retrieved on 6 October 2011.

- Plasticisers and Flexible PVC information centre – Diisodecyl phthalate (DIDP) Archived 18 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Didp-facts.com (13 April 2006). Retrieved on 28 January 2016.

- "Safety Assessment ofDi(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP)Released from PVC Medical Devices" (PDF).

- "China's PVC pipe makers under pressure to give up lead stabilizers". Archived from the original on 11 September 2013.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "ESPA | Lead replacement". European Stabiliser Producers Association. Archived from the original on 5 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- "VinylPlus Progress Report 2016" (PDF). VinylPlus. 30 April 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2016.

- Creech Jr, J. L.; Johnson, M. N. (March 1974). "Angiosarcoma of liver in the manufacture of polyvinyl chloride". Journal of Occupational Medicine. 16 (3): 150–1. PMID 4856325.

- Steiglitz, L., and Vogg, H. (February 1988) "Formation Decomposition of Polychlorodibenzodioxins and Furans in Municipal Waste" Report KFK4379, Laboratorium fur Isotopentechnik, Institut for Heize Chemi, Kerforschungszentrum Karlsruhe.

- Costner, Pat (2005) "Estimating Releases and Prioritizing Sources in the Context of the Stockholm Convention" Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine, International POPs Elimination Network, Mexico.

- Beychok, M.R. (1987). "A data base of dioxin and furan emissions from municipal refuse incinerators". Atmospheric Environment. 21 (1): 29–36. Bibcode:1987AtmEn..21...29B. doi:10.1016/0004-6981(87)90267-8.

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Polyvinyl Chloride Plastics in Municipal Solid Waste Combustion NREL/TP-430- 5518, Golden CO, April 1993

- Rigo, H. G.; Chandler, A. J.; Lanier, W.S. (1995). The Relationship between Chlorine in Waste Streams and Dioxin Emissions from Waste Combustor Stacks (PDF). American Society of Mechanical Engineers Report CRTD. 36. New York, NY: American Society of Mechanical Engineers. ISBN 978-0-7918-1222-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- Katami, Takeo; Yasuhara, Akio; Okuda, Toshikazu; Shibamoto, Takayuki; et al. (2002). "Formation of PCDDs, PCDFs, and Coplanar PCBs from Polyvinyl Chloride during Combustion in an Incinerator". Environ. Sci. Technol. 36 (6): 1320–1324. Bibcode:2002EnST...36.1320K. doi:10.1021/es0109904. PMID 11944687.

- Wagner, J.; Green, A. (1993). "Correlation of chlorinated organic compound emissions from incineration with chlorinated organic input". Chemosphere. 26 (11): 2039–2054. Bibcode:1993Chmsp..26.2039W. doi:10.1016/0045-6535(93)90030-9.

- Thornton, Joe (2002). Environmental Impacts of polyvinyl Chloride Building Materials (PDF). Washington, DC: Healthy Building Network. ISBN 978-0-9724632-0-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 September 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- The USGBC document; An analysis by the Healthy Building NEtwork Archived 2 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Wikstrom, Evalena; G. Lofvenius; C. Rappe; S. Marklund (1996). "Influence of Level and Form of Chlorine on the Formation of Chlorinated Dioxins, Dibenzofurans, and Benzenes during Combustion of an Artificial Fuel in a Laboratory Reactor". Environmental Science & Technology. 30 (5): 1637–1644. Bibcode:1996EnST...30.1637W. doi:10.1021/es9506364.

- Environmental issues of PVC. European Commission. Brussels, 26 July 2000

- Life Cycle Assessment of PVC and of principal competing materials Commissioned by the European Commission. European Commission (July 2004), p. 96

- Waste Hierarchy. Wtert.eu. Retrieved on 28 January 2016.

- "EUR-Lex – 32008L0098 – EN – EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- Home – Vinyl 2010 The European PVC industry commitment to Sustainability. Vinyl2010.org (22 June 2011). Retrieved on 6 October 2011.

- Our Voluntary Commitment. vinylplus.eu

- Incentives to collect and recycle. Recovinyl.com. Retrieved on 28 January 2016.

- https://vinylplus.eu/uploads/images/ProgressReport2019/VinylPlus%20Progress%20Report%202019_sp.pdf

- Solvay, asking more from chemistry. Solvayplastics.com (15 July 2013). Retrieved on 28 January 2016.

- Solvay, asking more from chemistry. Solvayplastics.com (15 July 2013). Retrieved on 28 January 2016.

- "CHW Switches to PVC/DEHP-Free Products to Improve Patient Safety and Protect the Environment". Business Wire. 21 November 2005.

- Smock, Doug (19 January 2012) Kaiser Permanente bans PVC tubing and bags. plasticstoday.com

- "PVC Policies Across the World". chej.org. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- "Vinyl Gloves: Causes For Concern" (PDF). Ansell (glove manufacturer). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- London 2012 Use of PVC Policy. independent.gov.uk.

- London 2012. independent.gov.uk.

- Clark, Anthony (31 July 2012) PVC at Olympics destined for reuse or recycling. plasticsnews.com

Bibliography

- Titow, W. (1984). PVC Technology. London: Elsevier Applied Science Publishers. ISBN 978-0-85334-249-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Polyvinyl chloride. |