Red wall (British politics)

The red wall, also referred to as Labour heartlands[1] and Labour's red wall, is a term used in the politics of the United Kingdom to describe a set of constituencies in the Midlands, Yorkshire and Northern England which historically tended to support the Labour Party. The term was coined in 2019 by pollster James Kanagasooriam.[2]

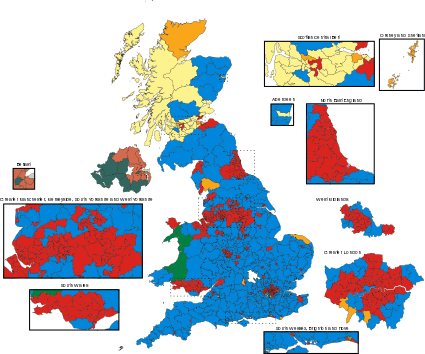

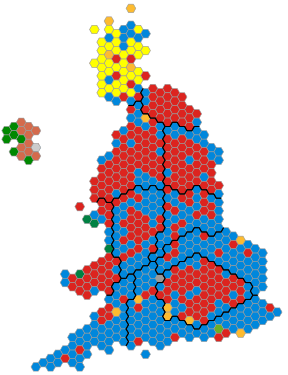

When viewed on a map of previous results, the block of seats held by the party resembled the shape of a red wall, coloured red, which has traditionally been used to represent Labour. This effect is exaggerated when results are projected into a map showing equal-size constituencies: in 2017, continuous blocks of red spanned the longitudinal distance across the North of England. In the 2019 general election, many of these constituencies uncharacteristically supported the Conservative Party. Press coverage described the red wall as having "turned blue", "crumbled",[3] "fallen",[4] or having been "demolished".[1]

The red wall metaphor has been criticised as a generalisation. Lewis Baston argues that the "red wall" is politically diverse, and includes bellwether seats which swung with the national trend, as well as former mining and industrial seats which show a more unusual shift.[5] In an article for The Daily Telegraph in 2020, Royston Smith MP for Southampton Itchen made the case that his seat in post-industrial Southampton was one the first red wall seat gained from the Labour Party (UK) when he became the Conservative MP for the city in the 2015 United Kingdom general election.[6]

Background

In 2014, political scientist Matthew Goodwin and Robert Ford documented the erosion by UKIP of the Labour-supporting working-class vote in Revolt on the Right.[7]

The Conservatives gained six previously safe Northern & Midlands Labour seats in the 2017 election: NE Derbyshire[8], Walsall North[9], Mansfield[10], Stoke-on-Trent South[11], Middlesbrough South & East Cleveland and Copeland (held from the 2017 Copeland by-election). In 2019, the Conservatives increased their majority in the seats previously gained.

Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage has suggested prior support of many northern Labour voters for UKIP and the Brexit Party made it easier for them to vote Conservative.[12]

2019 general election results

.svg.png)

(animated version available here)

In the 2019 general election, the Conservative Party gained 48 seats net in England. The Labour Party lost 47 seats net in England,[13] losing approximately 20% of its 2017 general election support in red wall seats.[14] All of these seats voted to leave the EU by substantial margins, and Brexit appears to have played a role in these seat changes.

Voters in Bolsover[15] and swing voters of the type thought to be typified by Workington man cited Brexit and the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn as reasons why they chose not to vote Labour. Labour lost so much support in the red wall in some seats, like Sedgefield, Ashfield and Workington, that even without the vote increase for the Conservatives, the Conservatives would have still have taken those seats.[14] Notable examples of "red wall" constituencies taken by the Conservatives include:

| Constituency | County | % Leave in 2016 EU referendum |

Description | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bassetlaw | Nottinghamshire | 68.3% | Held by Labour since 1935. The Conservatives won more than half of the vote share, with a Labour to Conservative swing of 18.4%, the largest in the country, and a majority of over 14,000 votes for the new MP. |

[15][3] |

| Heywood and Middleton | Greater Manchester | 62.4% | Held by Labour since its creation in 1983, it was almost lost to UKIP at a 2014 by-election in which Labour retained the seat by just 617 votes, but Labour majorities had recovered in 2015 and 2017 to over 5,000 and 7,000 respectively. By-elections usually have significantly lower levels of voter turnout compared to ordinary general elections in the UK. | [16] |

| Bishop Auckland | County Durham | 60.6% | Held by Labour at every UK general election except one since 1918, though by 2017 the majority had been reduced to just 502 votes. Returned a Conservative MP for the first time in its 134-year history, with a majority of 7,962. |

[15][4] |

| Blyth Valley | Northumberland | 59.8% | Held by Labour at every election except one since creation in 1950. The constituency declaration shortly after 11:30pm, was the election's first flip and regarded as an early sign of the electoral trend. |

[1][4][17] |

| Bolsover | Derbyshire | 70.2% | Held by Labour since its creation in 1950. 87-year old Socialist Campaign Group stalwart Dennis Skinner was defeated, having held the seat for 49 years (since 1970). |

[15][18] |

| Don Valley | South Yorkshire | 68.5% | Held by Labour since 1922. Caroline Flint, previously a Labour minister and Leave supporter, was defeated having served since 1997. |

[1][4] |

| Dudley North | West Midlands | 71.4% | Held by Labour since creation in 1997 (predecessor seats since 1970). Won by a majority of 11,533 on a Labour to Conservative swing of 15.8%. Retiring Labour MP was Ian Austin who became Independent and encouraged people to vote Conservative. |

[3] |

| Leigh | Greater Manchester | 63.4% | Held by Labour since 1922. Formerly the seat of Andy Burnham from 2001 to 2017 when he became Mayor of Greater Manchester. |

[3] |

| Sedgefield | County Durham | 58.9% | Held by Labour since 1935 (although the seat was abolished 1974–1983). Formerly the seat of Prime Minister Tony Blair from his first election to the Commons in 1983 until his resignation from Parliament in June 2007. |

[1][4] |

| Wakefield | West Yorkshire | 62.6% | Held by Labour since a by-election in 1932, although the majority in 1983 was only 360 votes, and since 2010 had been marginal. The incumbent MP Mary Creagh was a prominent opponent of Brexit. Creagh confronted Labour Party leader Jeremy Corbyn in Parliament five days after the election. | [19][20][21][22] |

| Workington | Cumbria | 60.3% | Held by Labour at every election except one since creation in 1918. "Workington man" was a profile seen as typical of northern, older, male, working-class voters who watch rugby league. Won by Mark Jenkinson, previously a candidate in Workington for UKIP, with a majority of 4,176. |

[1][14][23] |

| Ashfield | Nottinghamshire | 70.5% | Labour since 1955, except for a brief Conservative by-election victory in 1977-79, it was won by Gloria De Piero in 2010 with a majority of 192 votes for Labour. She stood down in 2019, and her former office manager Lee Anderson took the seat after defecting to the Conservatives. Labour finished third behind local independent Jason Zadrozny, who also stood on a Eurosceptic platform. | [24] |

Use in other countries

Journalist Nicholas Burgess Farrell has used the term to describe the Red belt, historically left-supporting regions of Italy, such as Emilia-Romagna which are under comparable pressure by Matteo Salvini and his right-wing populist Lega Nord party.[25]

See also

- Blue wall (politics)

- 2015 United Kingdom general election in Scotland, when Labour support, particularly in the Central Belt, was lost to the SNP, in what has been termed the "tartan wall"[26]

References

- Halliday, Josh (13 December 2019). "Labour's 'red wall' demolished by Tory onslaught". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- Singh, Matt (2019-12-19). "The first mention of the red wallhttps://twitter.com/jameskanag/status/1161639307536457730 …". @MattSingh_. Retrieved 2019-12-23. External link in

|title=(help) - Wainwright, Daniel (13 December 2019). "General election 2019: How Labour's 'red wall' turned blue". BBC News. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- O'Neill, Brendan (13 December 2019). "The fall of Labour's 'Red Wall' is a moment to celebrate". The Spectator. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- Baston, Lewis (18 December 2019). "The myth of the red wall". The Critic. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- "Let's not forget about the old 'Red Wall' seats down South that need levelling up".

- Bickerton, Chris (2019-12-19). "Labour's lost working-class voters have gone for good | Chris Bickerton". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- "Lee Rowley: North East Derbyshire was a forerunner of this election victory. Here's what we did to win again". Conservative Home. Retrieved 2020-03-06.

- Leather, Harry. "Walsall General Election results: Labour's David Winnick loses seat he had held since 1979". www.expressandstar.com. Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- "Ben Bradley: Voters tore down the Red Wall because they were sick of Labour talking down to them and holding them back". Conservative Home. Retrieved 2020-03-06.

- "Election results 2017: Tories gain Stoke-on-Trent South seat after 82 years". BBC News. 9 June 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- "https://twitter.com/nigel_farage/status/1205880267220668416". Twitter. Retrieved 2020-06-07. External link in

|title=(help) - "General election 2019: England results". BBC News. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- Miscampbell, Guy (2019-12-18). "How the Tories won over Workington Man". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- "Where did it all go wrong for Jeremy Corbyn and Labour?". YouTube. Channel 4 News. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- "Heywood and Middleton (UK Parliament constituency)", Wikipedia, 2020-01-07, retrieved 2020-01-09

- "Blyth Valley election result: Shock win as Tories take Labour seat". BBC News. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- Pittam, David (13 December 2019). "General election 2019: How Dennis Skinner lost his Bolsover seat". BBC News. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- "General election 2019: Conservatives take Wakefield from Labour". BBC News. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- "The inside story of how Labour lost Wakefield for the first time since the 1930s at the 2019 General Election". Yorkshire Evening Post. Leeds. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- Gittins, Holly (13 December 2019). "Conservatives win Wakefield for first time in nearly 90 years". Wakefield Express. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- "Mary Creagh on Jeremy Corbyn: 'He should be apologising'". BBC News. 17 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- "Election results 2019: Conservatives win Workington from Labour". BBC News. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- "Lee Anderson (British politician)", Wikipedia, 2020-01-08, retrieved 2020-01-09

- "Salvini's plan to smash Italy's red wall". UnHerd. 2020-01-24. Retrieved 2020-06-07.

- correspondent, Libby Brooks Scotland (2020-02-15). "Scottish Labour urges UK party to learn from fall of 'tartan wall'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-03-06.