Crewe

Crewe (/kruː/) is a railway town and civil parish within the borough of Cheshire East and the ceremonial county of Cheshire, England. The Crewe built-up area had a total population of 71,722 in 2011, which also covers parts of the adjacent civil parishes of Willaston and Wistaston.[1]

| Crewe | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

Crewe town centre looking towards the Market Hall | |

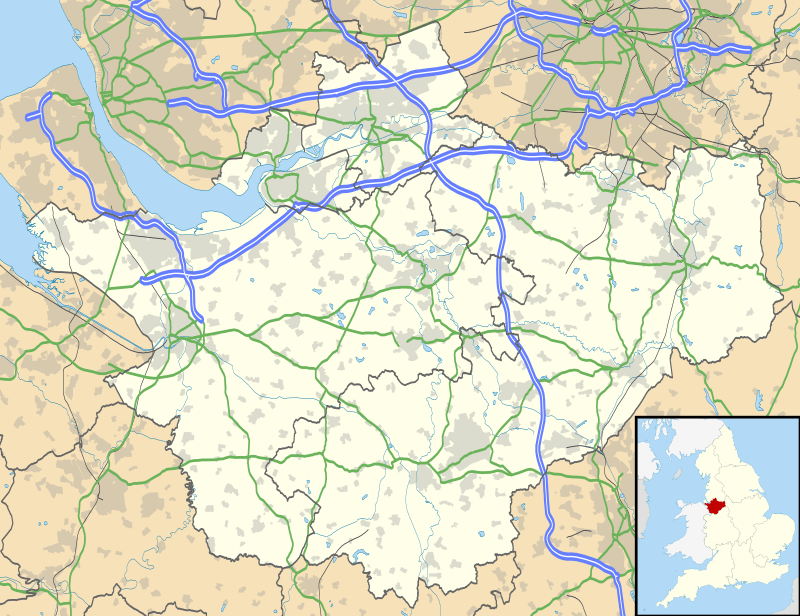

Crewe Location within Cheshire | |

| Population | 71,722 (built-up area, 2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SJ705557 |

| • London | 147 miles (237 km)[2] SE |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CREWE |

| Postcode district | CW1-CW3 |

| Dialling code | 01270 |

| Police | Cheshire |

| Fire | Cheshire |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | Crewe Town Council |

Crewe is perhaps best known as a large railway junction and home to Crewe Works; for many years, it was a major railway engineering facility for manufacturing and overhauling locomotives, but now much reduced in size. From 1946 until 2002, it was also the home of Rolls-Royce motor car production. The Pyms Lane factory on the west of the town now exclusively produces Bentley motor cars. Crewe is 158 miles (254 km) north of London and 35 miles (56 km) south of Manchester.

History

Medieval

The name derives from an Old Welsh word criu, meaning 'weir' or 'crossing'.[3] The earliest record is in the Domesday Book, where it is written as Creu.

Modern

The modern urban settlement of Crewe was not formally planned out until 1843 by Joseph Locke to consolidate the "railway colony" that had grown up since around 1840–41 in the area near to the railway junction station opened in 1837, even though it was called Crewe by many, from the start.[4][5] Crewe was thus named after the railway station, rather than the other way round.

Crewe was founded in the township of Monks Coppenhall which, with the township of Church Coppenhall, formed the ancient parish of Coppenhall.[6] The railway station was named after the township of Crewe (then, part of the ancient parish of Barthomley) in which it was located.[7] Eventually, the township of Crewe became a civil parish in its own right also named, rather confusingly, Crewe.[8] This civil parish changed its name to Crewe Green in 1974 to avoid confusion with the adjacent town, which had been made a municipal borough in 1877.[9]

The railway station remained part of the civil parish of Crewe, outside the boundary of the municipal borough until 1936.[10] So, throughout its history, the town of Crewe has neither been part of, nor has it encompassed first the township of Crewe, later the civil parish of Crewe, and later still the civil parish of Crewe Green adjacent to it, even though these places were the direct origin of the name of the town via the railway station which was also not part of the town before 1936. An old, local riddle describes the somewhat unusual states of affairs: "The place which is Crewe is not Crewe, and the place which is not Crewe is Crewe."[11]

Until the Grand Junction Railway (GJR) company chose Crewe as the site for its locomotive works and railway station in the late 1830s, Crewe was a village with a population (c. 1831) of just 70 residents.[12] Winsford, 7 miles (11 km) to the north, had rejected an earlier proposal, as had local landowners in neighbouring Nantwich, 4 miles (6 km) away. Crewe railway station was built in fields near to Crewe Hall and was completed in 1837.

A new town grew up, in the parishes of Monks Coppenhall and Church Coppenhall, alongside the increasingly busy station, with the population expanding to reach 40,000 by 1871. GJR chief engineer Joseph Locke helped lay out the town.[12]

The town has a large park, Queen's Park (laid out by engineer Francis Webb), the land for which was donated by the London and North Western Railway, the successor to the GJR. It has been suggested that their motivation was to prevent the rival Great Western Railway building a station on the site, but the available evidence indicates otherwise.[13]

The railway provided an endowment towards the building and upkeep of Christ Church. Until 1897 its vicar, non-conformist ministers and schoolteachers received concessionary passes, the school having been established in 1842. The company provided a doctor's surgery with a scheme of health insurance. A gasworks was built and the works water supply was adapted to provide drinking water and a public baths. The railway also opened a cheese market in 1854 and a clothing factory for John Compton who provided the company uniforms, while McCorquodale of Liverpool set up a printing works.

During World War II the strategic presence of the railways and Rolls-Royce engineering works (turned over to producing aircraft engines) made Crewe a target for enemy air raids, and it was in the flight path to Liverpool.[14] The borough lost 35 civilians to these,[15] the worst raid was on 29 August 1940 when some 50 houses were destroyed, close to the station.[16]

Crewe crater on Mars is named after the town of Crewe. Crewe was described by author Alan Garner in his novel Red Shift as "the ultimate reality".

Governance

Crewe is within the United Kingdom Parliamentary constituency of Crewe and Nantwich. Crewe is within the ceremonial county of Cheshire.

At local government level, Crewe is a community administered by Cheshire East Council and, from 4 April 2013, by Crewe Town Council.

Economy

The railways still play a part in local industry at Crewe Works, which carries out train maintenance and inspection. It has been owned by Bombardier Transportation since 2001. At its height, the site employed over 20,000 people, but by 2005 fewer than 1,000 remained, with a further 270 redundancies announced in November of that year. Much of the site once occupied by the works has been sold and is now occupied by a supermarket, leisure park, and a large new health centre.

There is still an electric locomotive maintenance depot to the north of the railway station, operated by DB Cargo UK. The diesel locomotive maintenance depot having closed in 2003, reopened in 2015 as a maintenance facility for Locomotive Services Limited having undergone major structural repairs.[17][18]

The Bentley car factory is on Pyms Lane to the west of town. As of early 2010, there are about 3,500 working at the site.[19] The factory used to produce Rolls-Royce cars, until the licence for the brand transferred from Bentley's owners Volkswagen to rival BMW in 2003.

There is a BAE Systems Land & Armaments factory in the village of Radway Green near Alsager, producing small arms ammunition for the British armed forces.

The headquarters of Focus DIY, which went into administration in 2011, was in the town. Off-licence chain Bargain Booze is also Crewe-based. It was bought-out in 2018 by Sir Anwar Pervez' conglomerate Bestway for £7m,[20] putting drinks retailing alongside its Manchester-based Well Pharmacy.

Several business parks around the town host light industry and offices. Crewe Business Park is a 67-acre site with offices, research and IT manufacturing. Major presences on the site include Air Products, Barclay's and Fujitsu. The 12 acre Crewe Gates Industrial Estate is adjacent to Crewe Business Park, with smaller industry including the ice cream van manufacturer Whitby Morrison. The Weston Gate area has light industry and distribution. Marshfield Bank Employment Park is to the west of the town, and includes offices, manufacturing and distribution. There are industrial and light industrial units at Radway Green.

The town has two small shopping centres: the Victoria Centre and the Market Centre. There are indoor and outdoor markets throughout the week. Grand Junction Retail Park is just outside the centre of town. Nantwich Road provides a wide range of secondary local shops, with a variety of small retailers and estate agents.

The Market Centre is the largest shopping centre in Crewe. It is situated in the heart of the town centre with 22 national retailers including River Island, Wilkinsons, Argos, Iceland and Dorothy Perkins. There are three large car parks nearby and Crewe Bus Station is a five-minutes walk from the shopping centre. It has a weekly footfall of approximately 100,000 visitors.

Developments

A planned redevelopment of Crewe's town centre, including the current bus station and main shopping area were abandoned because of "difficult economic conditions" during 2008.[21]

There were also plans to revamp the railway station which involved moving it to Basford. This was pending a public consultation by Network Rail scheduled for autumn 2008, but no such public consultation was done. The plan was abandoned and maintenance work was carried out on the current station instead.[22]

Cheshire East Council developed a new regeneration master plan for Crewe,[23] which included the opening of a new Lifestyle Centre, with a new swimming pool, gym and library.

Crewe has been proposed as the site of a transport hub for the new HS2 line, with development planned for completion in 2027.[24]

Transport

Crewe railway station is less than a mile from Crewe town centre, although it was not incorporated into the then Borough of Crewe until 1937. It is one of the largest stations in the North West and a major interchange station on the West Coast Main Line. It has 12 platforms in use and has a direct service to London Euston (average journey time of around 1 hour 35 minutes), Edinburgh, Cardiff, Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, Glasgow, Derby, Stoke-on-Trent, Chester, Wrexham and Holyhead for the ferry connections to Dublin Port. Many other towns and cities also have railway connections to Crewe.

Crewe is on the A500, A530 and A534 roads, and is less than 5 miles (8.0 km) from the M6 motorway.[25]

The main bus company in Crewe is D&G Bus following the reduction of funding given to Arriva North West, who still run longer distance services to Chester, Northwich, Macclesfield and Winsford. BakerBus formerly ran buses in Crewe, but their operations were sold to D&G in December 2014. First Potteries operate a single service (route 3) running to Stoke-on-Trent via Kidsgrove.[26]

The closest airport to Crewe is Manchester Airport, which is 30 miles (48 km) away. Next closest is Liverpool John Lennon Airport, 40 miles (64 km) away.

Culture

Crewe Heritage Centre is located in the old LMS railway yard for Crewe railway station. The museum has three signal boxes and an extensive miniature railway with steam, diesel and electric traction. The most prominent exhibit of the museum is the British Rail Class 370 Advanced Passenger Train.

The Grade II-listed Edwardian Lyceum Theatre is in the centre of Crewe. It was built in 1911 and shows drama, ballet, opera, music, comedy and pantomime.[27] The theatre was originally located on Heath Street from 1882. The Axis Arts Centre is on the Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU) campus in Crewe. It relocated from the university's Alsager Campus when it closed. The centre has a programme of touring new performance and visual art work.[28] The Axis centre closed at the end of the spring 2019 season with the withdrawal of MMU from the Crewe campus.[29] The Box on Pedley Street is the town's main local music venue.

Both the Lyceum Theatre and the Axis Arts Centre feature galleries. The private Livingroom art gallery is on Prince Albert Street. The town's main library is on Prince Albert Square, opposite the Municipal Buildings.

Crewe has six Anglican churches, three Methodist, one Roman Catholic (which has a weekly mass in Polish) and two Baptist.[30]

There is a museum dedicated to Primitive Methodism in the nearby village of Englesea-Brook.[31]

The Jacobean mansion Crewe Hall is located to the east of the town near Crewe Green. It is a grade I listed building, built in 1615–36 for Sir Randolph Crewe. Today, it is used as a hotel, restaurant and health club.

There is a multiplex ODEON cinema on Phoenix Leisure Park on the edge of the town centre, as well as a bowling alley and Mecca bingo hall.

Queens Park is the town's main park; £6.5 million was spent on its restoration.[32] It features walkways, a children's play area, crown green bowling, putting, a boating lake, grassed areas, memorials and a café.[33] Jubilee Gardens are in Hightown and there is also a park on Westminster Street.

In 2019, Crewe hosted Pride in the Park (previously held at Tatton Park in 2018) in Queens Park. The 2020 event will be on 12 September.[34]

Media

The weekly Crewe Chronicle, the Crewe and Nantwich Guardian and the daily Sentinel newspapers all cover the town. The local radio station is The Cat[35] broadcasting on 107.9FM from the Cheshire College South and West building covering the town along with Nantwich and other local settlements. Other radio stations that cover the area include Silk 106.9 from Macclesfield, Signal 1 and Signal 2 from Stoke-on-Trent and BBC Radio Stoke. Nantwich-based online-only station RedShift Radio also cover the area.

The Crewe News is a hyperlocal blog publishing local news, business, events and sports news.[36]

Education

Cheshire has adopted the comprehensive school model of secondary education, so all of the schools under its control cater for pupils of all levels of ability.[37] Until the late 1970s Crewe had two grammar schools, Crewe Grammar School for Boys, now Ruskin High School and Crewe Grammar School for Girls, now the Oaks Academy (formerly Kings Grove School). The town's two other secondary schools are Sir William Stanier Community School, a specialist technology and arts academy, and St. Thomas More Catholic High School, specialising in mathematics and computing and modern foreign languages.

Although there are eight schools for those aged 11–16 in Crewe and its surrounding area, South Cheshire College is one of only two local providers of education for pupils aged 16 and over, and the only one in Crewe. The college also provides educational programmes for adults, leading to qualifications such as Higher National Diplomas (HNDs) or foundation degrees. In the 2006–07 academic year 2,532 students aged 16–18 were enrolled, along with 3,721 adults.[38]

Manchester Metropolitan University's (MMU) Cheshire Faculty is based in Crewe, in a part of town which has been rebranded as the University Quadrant. The campus offers undergraduate and postgraduate courses in five areas: business and management, contemporary arts, exercise and sport science, interdisciplinary studies, education and teacher training.[39] The campus underwent a £70 million investment in its facilities and buildings in 2015.[40] The campus was used as a pre-games training camp for the London 2012 Olympic Games.[41]

Sport

Crewe's local football club is Crewe Alexandra. During the late 20th century the club enjoyed something of a renaissance under the management of Dario Gradi, playing in the First Division – the second tier of the professional pyramid – for five seasons from 1997 to 2002. Crewe Alexandra will play in League One (the third tier) in the 2020-21 season, having been promoted from League Two Two in June 2020. In 2013 the club won its first major silverware after beating Southend United 2-0 in the EFL Trophy final at Wembley.

Crewe Alexandra has a reputation of developing young players through its youth ranks; since the early 1980s Geoff Thomas, Danny Murphy, Craig Hignett, David Platt, Rob Jones, Neil Lennon, Dean Ashton and Nick Powell have all passed through the club. Internationals Bruce Grobbelaar and Stan Bowles were also on the books at one time in their careers. Possibly their most famous home-grown player was Frank Blunstone, born in the town in 1934, who was transferred from "The Alex" to Chelsea in 1953, and went on to win five England caps.

Crewe's local rugby clubs are both based in or near Nantwich. The Crewe & Nantwich Steamers (formerly Crewe Wolves), who play in the Rugby League Conference, are based at Barony Park, Nantwich, while Crewe and Nantwich RUFC play their home games at the Vagrants Sports Ground in Willaston.

Speedway racing was staged in Crewe in the pioneer days of the late 1920s to early 1930s. The venue was the stadium in Earle Street which also operated in the 1970s. The Crewe Kings raced in the lower division – British League Division Two, then the National League – from 1969 until 1975. At the time the track was the longest and fastest in the UK.[42] Amongst their riders were Phil Crump (father of Jason Crump), Les Collins (brother of Peter Collins), Dave Morton (brother of Chris Morton), Geoff Curtis, John Jackson, Jack Millen and Dave Parry. The stadium has since been demolished to be replaced by a retail park housing a number of national companies.

The Crewe Railroaders are the town's American football team, currently competing in the BAFA Central League Division 2 and the subject of the film Gridiron UK which premiered at the Lyceum Theatre on 29 September 2016.

Crewe also has its own roller derby team, Railtown Loco Rollers, founded in September 2013. They skate at Sir William Stanier Leisure Centre and compete with skaters and teams from all over the North West.

Crewe's main leisure facility is the Crewe Lifestyle Centre, which now houses Crewe's Swimming Pool after the Flag Lane premises closed in 2016.[43] Other notable leisure facilities include Sir William Stanier Leisure Centre and Victoria Community Centre.

Notable people

1850 to 1950

- William Hope (1863 – 1933) pioneer of spirit photography,[44] based in Crewe, member of the Crewe Circle

- Thomas Nevitt (1864 in Crewe – 1932) member of the Queensland Legislative Council

- Ada Nield Chew, (1870 – 1945) suffragette wrote a series of letters to the Crewe Chronicle, signed "A Crewe Factory Girl"[45]

- William Edwin Wheeldon (1898 in Crewe – 1960) British co-operator[46] and municipal politician from Birmingham and MP

- John Warburton (1903-?), English Football League player, mostly for Wrexham and Crewe Alexandra.[47]

- William Cooper (real name Harry Summerfield Hoff), (1910 – 2002) novelist,[48] lived at 99 Brooklyn Street

- Blaster Bates a.k.a. Derek Macintosh Bates (1923 in Crewe – 2006), an English explosives and demolition expert and raconteur

- Gwyneth Patricia Dunwoody (1930 – 2008) British Labour Party politician,[49] MP for Exeter from 1966 to 1970, then for Crewe, later Crewe and Nantwich from 1974

- Harold Hankins CBE FREng (1930 in Crewe – 2009) was a British electrical engineer[50] and the first Vice-Chancellor of UMIST.

- Professor Christine Dean BA. MD. FRCPsych (born in Crewe 1939) London psychiatrist, attended Crewe County Grammar School

- Chris Hughes (born 1947) one of Britain's top quizzers, featuring in Eggheads. Lives in Crewe

- Janet Elizabeth Ann Dean (born 1949 in Crewe) British Labour Party MP for Burton from 1997 to 2010

1950 on

- Tom Levitt (born 1954 in Crewe) Labour Party politician who was the MP for High Peak

- Carol Jean Mountford (born 1954 in Crewe), known as Kali, Labour Party politician and MP for Colne Valley

- Mark Price, Baron Price (born 1961 in Crewe) businessman, was MD of Waitrose and Deputy Chairman of John Lewis Partnership

- John Mark Ainsley (born 1963 in Crewe) English lyric tenor of baroque music and the works of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

- Carl Ashmore (born 1968) children's author

- Anthony Edward Timpson (born 1973) British Conservative MP for Crewe and Nantwich (2008–2017) and Eddisbury (from 2019).

- Paul Christopher Maynard (born 1975 in Crewe) British Conservative MP for Blackpool North and Cleveleys and Rail Minister

- Any Trouble a British rock band, originating from Crewe in 1975, best known for their early 1980s recordings

- Carey Willetts (born 1976 in Crewe) British musician, songwriter, and producer.

- Mackenzie Taylor (1978–2010) British comic, writer and director. Born in Crewe

- Adam Peter Rickitt (born 1978) English actor,[51] singer and model and charity fundraiser

- Lauren Jane Moss (born 1987 in Crewe) Australian politician

Sport

- Sir Philip Craven, MBE (born 1950) president of the International Paralympic Committee (IPC), lives in Shavington.[52]

- Neil Brooks, (born in Crewe 1962) Australian Olympic swimming gold medallist

- John Edward Morris, (born 1964) former English cricketer, played most for Derbyshire.

- David Gilford, (born 1965) European Tour and Ryder Cup golfer (1991, 1995) is from Crewe

- Mark Cueto, MBE (born 1979) international rugby and lions player currently playing for the Sale Sharks

- Craig Jones (1985 in Crewe – 2008) English motorcycle racer who grew up in Northwich

- Shanaze Reade, (born 1988) world BMX and track cycling champion

- Muthu Alagappan (born c. 1990 in Crewe) medical student known in the USA for his professional basketball analytics

- Bryony Page, (born 1990 in Crewe) an Olympic silver medal winning trampolinist, raised in the village of Wrenbury, 8.5 miles from the town.

Town twinning

|

References

Notes

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Crewe built up area (1119884750)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "Coordinate Distance Calculator". boulter.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- Mills, David (20 October 2011). A Dictionary of British Place-Names. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780199609086. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- "Cheshire Historic Towns Survey: Crewe – Archaeological Assessment". Cheshire County Council & English Heritage. 2003. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2010.

- Ollerhead (2008, pp. 7, 10, 16); Chambers (2007, pp. 76, 94)

- Youngs (1991, pp. 15–16); Dunn (1989, p. 26); Ollerhead (2008, p. 10)

- Youngs (1991, p. 16); Chambers (2007, pp. 76, 94)

- Youngs (1991, p. 16)

- Crewe (near Wybunbury), GENUKI (UK & Ireland Genealogy), archived from the original on 1 December 2008, retrieved 3 February 2009

- Ollerhead (2008, p. 10)

- Curran et al. (1984, p. 2)

- Glancey, Jonathan (6 December 2005), "The beauty of Crewe", The Guardian, London, retrieved 10 August 2007

- Archived 21 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine states: "This can now be totally dispelled as records show the LNWR Co. originally thought their line to Chester would run alongside the river. However, it was discovered the ground was not firm enough and a more northerly route was decided upon. Had the original thought gone ahead it would have taken the land that was eventually used for Queens Park. It is obvious that a rumour became mixed with a proposal to open a station on the present Chester line called Queens Park Halt. To further clarify the situation an entry on the 18th December, 1886, in the Minute Book of the board of directors of the LNWR, refers to the area being given for a public park."

- Discovering Wartime Cheshire 1939-1945. Cheshire County Council Countryside and Recreation. 1985. pp. 47–48. ISBN 0-906759-20-X.

- Archived 8 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine CWGC civilian casualty record, Crewe Municipal Borough.

- Discovering Wartime Cheshire 1939-1945. p. 49.

- Crewe Diesel depot is biggest loss as EWS prepares for closure Rail issue 475 26 November 2003 page 6

- Hosking to lease Crewe depot Railways Illustrated issue 135 May 2014 page 10

- Mark Gillies (10 May 2010). "Going Back in Time at the Bentley Factory". Car and Driver blog. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- Fisher, Martyn (6 April 2018). "Bestway buys Bargain Booze". Better Wholesaling. Archived from the original on 6 April 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Developer confident of town upgrades in the face of downturn, Staffordshire Sentinel News and Media, 31 December 2008, retrieved 3 February 2009

- "The Sentinel". Archived from the original on 21 June 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- "Cheshire East Council Crewe Vision documents". Archived from the original on 13 September 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- "HS2 Birmingham to Crewe link planned to open six years early". BBC News. 30 November 2015. Archived from the original on 21 January 2016. Retrieved 16 January 2016.

- "Google Maps".

- "Timetables | Potteries". First Bus. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- "HQ Theatres". lyceumtheatre.net. Archived from the original on 5 September 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- Axis Arts Centre website Archived 22 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Neil Mackenzie (Spring 2019). "Spring Season 2019 – Welcome and goodbye!". Axis Arts Centre. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- "Crewe Places of Worship, for Places of Worship in Crewe, Cheshire, UK". city-visitor.com. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- Englsea Brook Chapel and Museum website Archived 30 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Page not found". cheshireeast.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- "Queens Park, Crewe". www.cheshireeast.gov.uk. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- "About". Pride in the Park. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- "About Us". The Cat 107.9. The Cat Community Radio C.I.C. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- "Crewe News".

- Secondary Education, Cheshire County Council, archived from the original on 14 October 2008, retrieved 3 February 2009

- South Cheshire College (PDF), Ofsted, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2009, retrieved 3 February 2009

- "Profile: Manchester Metropolitan University", Times Online, London: Times Newspapers, 19 June 2008, archived from the original on 8 October 2008, retrieved 25 September 2018

- "MMU Cheshire". Study in Cheshire. Archived from the original on 3 April 2014. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- "2012 Pre-Games Training Camp". mmu.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- Bamford, R & Jarvis J.(2001). Homes of British Speedway. ISBN 0-7524-2210-3

- "Crewe Lifestyle Centre - Everybody Sport & Recreation". Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- The Guardian, Fri 29 Oct 2010 Archived 22 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine retrieved December 2017

- Doughan, David (2004), "Chew, Ada Nield (1870–1945)", Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, retrieved 15 November 2008

- HANSARD 1803–2005 → People (W) Mr William Wheeldon 1898-1960 Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine retrieved December 2017

- "Bangor City Players 1876-1939 Who Progressed Into The English Football League". The Citizens Choice. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- The Guardian, Norman Shrapnel, Sat 7 Sep 2002 Archived 22 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine retrieved December 2017

- The Guardian, Edward Pearce, Sat 19 Apr 2008 Archived 12 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine retrieved December 2017

- The Guardian, John Garside, Wed 5 Aug 2009 Archived 22 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine retrieved December 2017

- IMDb Database Archived 4 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine retrieved December 2017

- Crewe Lifestyle Centre officially opens Archived 31 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine Cheshire East Council. 27 May 2016.

- Linked Towns Archived 16 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Crewe & Nantwich Twinning Association

Bibliography

- Hornbrook, J (2009), Crewe and its People, Crewe, Cheshire: MPire Books, ISBN 978-0-9538877-2-9

- Chambers, S (2007), Crewe: A history, Chichester, Sussex: Phillimore, ISBN 978-1-86077-472-0

- Curran, H; Gilsenan, M; Owen, B; Owen, J (1984), Change at Crewe, Chester: Cheshire Libraries and Museums

- Dodgson, J. McN. (1971), The place-names of Cheshire. Part three: The place-names of Nantwich Hundred and Eddisbury Hundred, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-08049-5

- Dunn, F. I. (1987), The ancient parishes, townships and chapelries of Cheshire, Chester: Cheshire Record Office and Cheshire Diocesan Record Office, ISBN 0-906758-14-9

- Langston, K (2006), Made in Crewe: 150 years of engineering excellence, Horncastle, Lincolnshire: Mortons Media Group, ISBN 978-0-9552868-0-3

- Ollerhead, P (2008), Crewe: History and guide, Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7524-4654-7

- Youngs, F. A. (1991), Guide to the local administrative units of England. (Volume 1: Northern England), London: Royal Historical Society, ISBN 0-86193-127-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crewe. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Crewe. |

- Crewe Town Council

- Cheshire East Council

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Crewe Heritage Centre railway museum