County Durham

County Durham (/ˈdʌrəm/, locally /ˈdɜrəm/ ![]()

| County Durham | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceremonial county | |||

| |||

| |||

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom | ||

| Constituent country | England | ||

| Region | North East England | ||

| Established | Ancient | ||

| Ceremonial county | |||

| Lord Lieutenant | Susan Snowdon | ||

| High Sheriff | Peter Haswell Candler[1] (2019–20) | ||

| Area | 2,721 km2 (1,051 sq mi) | ||

| • Ranked | 18th of 48 | ||

| Population (mid-2019 est.) | 866,846 | ||

| • Ranked | 26th of 48 | ||

| Density | 324/km2 (840/sq mi) | ||

| Unitary authority | |||

| Council |  Durham County Council | ||

| Executive | Labour | ||

| Admin HQ | Durham | ||

| Area | 2,226 km2 (859 sq mi) | ||

| • Ranked | 7th of 326 | ||

| Population | 530,094 | ||

| • Ranked | 8th of 326 | ||

| Density | 237/km2 (610/sq mi) | ||

| ISO 3166-2 | GB-DUR | ||

| ONS code | 00EJ | ||

| GSS code | E06000047 | ||

| NUTS | UKC14 | ||

| Website | www | ||

Districts of County Durham Unitary | |||

| Districts |

* only the part of the borough north of the River Tees is within the ceremonial county of Durham. | ||

| Members of Parliament | List of MPs | ||

| Police | Durham Constabulary Cleveland Police (part) | ||

| Time zone | Greenwich Mean Time (UTC) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | British Summer Time (UTC+1) | ||

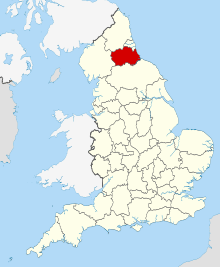

County Durham can refer to the modern ceremonial county, the smaller area of a unitary authority, or the historic county with different boundaries. The largest settlement in the ceremonial county is Darlington, closely followed by Hartlepool, Billingham and Stockton-on-Tees. It borders Tyne and Wear to the north-east, Northumberland to the north, Cumbria to the west and North Yorkshire to the south.[3] The area of the unitary authority, Durham County Council, does not include Darlington, Hartlepool or Stockton-on-Tees. The historic county's boundaries stretch between the rivers Tyne and Tees, thus including places such as Gateshead, Jarrow, South Shields and Sunderland, but do not include the part of the modern county south of the Tees.

During the Middle Ages, the county was an ecclesiastical centre, due largely to the presence of St Cuthbert's shrine in Durham Cathedral, and the extensive powers granted to the Bishop of Durham as ruler of the County Palatine of Durham. The county has a mixture of mining, farming and heavy railway heritage, with the latter especially noteworthy in the southeast of the county, in Darlington, Shildon and Stockton.[4] In the centre of the city of Durham, Durham Castle and Durham Cathedral are UNESCO-designated World Heritage Sites.

Etymology

Many counties are named after their principal town, and the expected form here would be Durhamshire, but this form has never been in common use. The ceremonial county is officially named Durham,[3] but the county has long been commonly known as County Durham and is the only English county name prefixed with "County" in common usage (the practice is common in Ireland). Its unusual naming (for an English shire) is explained to some extent by the relationship with the Bishops of Durham, who for centuries governed Durham as a county palatine (the County Palatine of Durham), outside the usual structure of county administration in England.

The situation regarding the formal name in modern local government is less clear. The structural change legislation[5] which in 2009 created the present unitary council (that covers a large part – but not all – of the ceremonial county) refers to "the county of County Durham" and names the new unitary district "County Durham" too. However, a later amendment to that legislation,[6] refers to the "county of Durham" and the amendment allows for the unitary council to name itself "The Durham Council". In the event the council retained the name of Durham County Council. With either option, the name does not include County Durham.

The former postal county was named "County Durham" to distinguish it from the post town of Durham.

Politics

Parliament

The county boundaries used for parliamentary constituencies are those used between 1974 and 1996 (i.e. consisting of only the area governed by Durham County Council and the Borough of Darlington). This area of the county elects seven Members of Parliament. As of the 2019 General Election, four of these MPs are Conservatives and three MPs are Labour. The rest of the ceremonial county is included in constituencies in the Cleveland parliamentary constituency area.

| 2019 General Election Results in County Durham | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Votes | % | Change from 2017 | Seats | Change from 2017 | ||||

| Conservative | 123,112 | 40.6% | 4 | ||||||

| Labour | 122,547 | 40.4% | 3 | ||||||

| Brexit | 25,444 | 8.4% | new | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Liberal Democrats | 21,356 | 7.0% | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Greens | 5,985 | 2.0% | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Others | 4,725 | 1.6% | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Total | 303,260 | 100.0 | 7 | ||||||

Local government

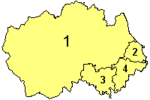

The ceremonial county of Durham is administered by four unitary authorities. The ceremonial county has no administrative function, but remains the area to which the Lord Lieutenant of Durham and the High Sheriff of Durham are appointed.

- County Durham (governed by Durham County Council): the unitary district was formed on 1 April 2009 replacing the previous two-tier system of a county council providing strategic services and seven district councils providing more local facilities. It has 126 councillors. The seven districts abolished were:[7][8]

- Chester-le-Street, including the Lumley, Pelton and Sacriston areas

- Derwentside, including Consett and Stanley

- City of Durham, including Durham city and the surrounding areas

- Easington, including Seaham and the new town of Peterlee

- Borough of Sedgefield, including Spennymoor and Newton Aycliffe

- Teesdale, including Barnard Castle and the villages of Teesdale

- Wear Valley, including Bishop Auckland, Crook, Willington, Hunwick, and the villages along Weardale

- The Borough of Darlington: before 1 April 1997, Darlington was a district in a two-tier arrangement with Durham County Council.[9]

- The Borough of Hartlepool: until 1 April 1996 the borough was one of four districts in the relatively short-lived county of Cleveland, which was abolished.[3][10]

- The part of the Borough of Stockton-on-Tees that is north of the centre of the River Tees. Stockton was also part of Cleveland until that county's abolition in 1996.[10] The remainder of the borough is part of the ceremonial county of North Yorkshire.[3]

Civil parishes

The county is partially parished.

Emergency services

Durham Constabulary operate in the area of the two unitary districts of County Durham and Darlington.[11] Ron Hogg was first elected the Durham Police and Crime Commissioner for the force on 15 November 2012. The other areas in the ceremonial county fall within the police area of the Cleveland Police.

Fire service areas follow the same areas as the police with County Durham and Darlington Fire and Rescue Service serving the two unitary districts of County Durham and Darlington and Cleveland Fire Brigade covering the rest. County Durham and Darlington Fire and Rescue Service is under the supervision of a combined fire authority consisting of 25 local councillors: 21 from Durham County Council and 4 from Darlington Borough Council.[12]

The North East Ambulance Service NHS Trust are responsible for providing NHS ambulance services throughout the ceremonial county, plus the boroughs of Middlesbrough and Redcar and Cleveland, which are south of the River Tees and therefore in North Yorkshire, but are also part of the North East England region.

Air Ambulance services are provided by the Great North Air Ambulance. The charity operates 3 helicopters including one at Durham Tees Valley Airport covering the County Durham area.

Teesdale and Weardale Search and Mountain Rescue Team, are based at Sniperly Farm in Durham City and respond to search and rescue incidents in the county.

History

Anglian Kingdom of Bernicia

Around AD 547, an Angle named Ida founded the kingdom of Bernicia after spotting the defensive potential of a large rock at Bamburgh, upon which many a fortification was thenceforth built.[13] Ida was able to forge, hold and consolidate the kingdom; although the native British tried to take back their land, the Angles triumphed and the kingdom endured.

Kingdom of Northumbria

In AD 604, Ida's grandson Æthelfrith forcibly merged Bernicia (ruled from Bamburgh) and Deira (ruled from York, which was known as Eforwic at the time) to create the Kingdom of Northumbria. In time, the realm was expanded, primarily through warfare and conquest; at its height, the kingdom stretched from the River Humber (from which the kingdom drew its name) to the Forth. Eventually, factional fighting and the rejuvenated strength of neighbouring kingdoms, most notably Mercia, led to Northumbria's decline.[13] The arrival of the Vikings hastened this decline, and the Scandinavian raiders eventually claimed the Deiran part of the kingdom in AD 867 (which became Jórvík). The land that would become County Durham now sat on the border with the Great Heathen Army, a border which today still (albeit with some adjustments over the years) forms the boundaries between Yorkshire and County Durham.

Despite their success south of the river Tees, the Vikings never fully conquered the Bernician part of Northumbria, despite the many raids they had carried out on the kingdom.[13] However, Viking control over the Danelaw, the central belt of Anglo-Saxon territory, resulted in Northumbria becoming isolated from the rest of Anglo-Saxon Britain. Scots invasions in the north pushed the kingdom's northern boundary back to the River Tweed, and the kingdom found itself reduced to a dependent earldom, its boundaries very close to those of modern-day Northumberland and County Durham. The kingdom was annexed into England in AD 954.

City of Durham founded

In AD 995, St Cuthbert's community, who had been transporting Cuthbert's remains around, partly in an attempt to avoid them falling into the hands of Viking raiders, settled at Dunholm (Durham) on a site that was defensively favourable due to the horseshoe-like path of the River Wear.[14] St Cuthbert's remains were placed in a shrine in the White Church, which was originally a wooden structure but was eventually fortified into a stone building.

County Palatine of Durham

Once the City of Durham had been founded, the Bishops of Durham gradually acquired the lands that would become County Durham. Bishop Aldhun began this process by procuring land in the Tees and Wear valleys, including Norton, Stockton, Escomb and Aucklandshire in 1018. In 1031, King Canute gave Staindrop to the Bishops. This territory continued to expand, and was eventually given the status of a liberty. Under the control of the Bishops of Durham, the land had various names: the "Liberty of Durham", "Liberty of St Cuthbert's Land" "the lands of St Cuthbert between Tyne and Tees" or "the Liberty of Haliwerfolc".[15]

The bishops' special jurisdiction rested on claims that King Ecgfrith of Northumbria had granted a substantial territory to St Cuthbert on his election to the see of Lindisfarne in 684. In about 883 a cathedral housing the saint's remains was established at Chester-le-Street and Guthfrith, King of York granted the community of St Cuthbert the area between the Tyne and the Wear, before the community reached its final destination in 995, in Durham.

Following the Norman invasion, the administrative machinery of government extended only slowly into northern England. Northumberland's first recorded Sheriff was Gilebert from 1076 until 1080 and a 12th-century record records Durham regarded as within the shire.[16] However the bishops disputed the authority of the sheriff of Northumberland and his officials, despite the second sheriff for example being the reputed slayer of Malcolm Canmore, King of Scots. The crown regarded Durham as falling within Northumberland until the late thirteenth century. Matters came to a head in 1293 when the bishop and his steward failed to attend proceedings of quo warranto held by the justices of Northumberland. The bishop's case went before parliament, where he stated that Durham lay outside the bounds of any English shire and that "from time immemorial it had been widely known that the sheriff of Northumberland was not sheriff of Durham nor entered within that liberty as sheriff. . . nor made there proclamations or attachments".[17] The arguments appear to have prevailed, as by the fourteenth century Durham was accepted as a liberty which received royal mandates direct. In effect it was a private shire, with the bishop appointing his own sheriff.[15] The area eventually became known as the "County Palatine of Durham".

Sadberge was a liberty, sometimes referred to as a county, within Northumberland. In 1189 it was purchased for the see but continued with a separate sheriff, coroner and court of pleas. In the 14th century Sadberge was included in Stockton ward and was itself divided into two wards. The division into the four wards of Chester-le-Street, Darlington, Easington and Stockton existed in the 13th century, each ward having its own coroner and a three-weekly court corresponding to the hundred court. The diocese was divided into the archdeaconries of Durham and Northumberland. The former is mentioned in 1072, and in 1291 included the deaneries of Chester-le-Street, Auckland, Lanchester and Darlington.

The term palatinus is applied to the bishop in 1293, and from the 13th century onwards the bishops frequently claimed the same rights in their lands as the king enjoyed in his kingdom.

Early administration

Overview

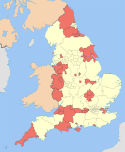

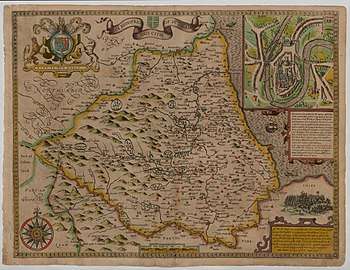

The historic boundaries of County Durham included a main body covering the catchment of the Pennines in the west, the River Tees in the south, the North Sea in the east and the Rivers Tyne and Derwent in the north.[18][19] The county palatinate also had a number of liberties: the Bedlingtonshire, Islandshire[20] and Norhamshire[21] exclaves within Northumberland, and the Craikshire exclave within the North Riding of Yorkshire. In 1831 the county covered an area of 679,530 acres (2,750.0 km2)[22] and had a population of 253,910.[23] These exclaves were included as part of the county for parliamentary electoral purposes until 1832, and for judicial and local-government purposes until the coming into force of the Counties (Detached Parts) Act 1844, which merged most remaining exclaves with their surrounding county. The boundaries of the county proper remained in use for administrative and ceremonial purposes until the 1972 Local Government Act.

The Early English and Norman period

Following the Battle of Hastings, William the Conqueror appointed Copsig as Earl of Northumbria, thereby bringing what would become County Durham under Copsig's control. Copsig was, just a few weeks later, killed in Newburn.[24] Having already being previously offended by the appointment of a non-Northumbrian as Bishop of Durham in 1042, the people of the region became increasingly rebellious.[24] In response, in January 1069, William despatched a large Norman army, under the command of Robert de Comines, to Durham City. The army, believed to consist of 700 cavalry (about one-third of the number of Norman knights who had participated in the Battle of Hastings),[24] entered the city, whereupon they were attacked, and defeated, by a Northumbrian assault force. The Northumbrians wiped out the entire Norman army, including Comines,[24] all except for one survivor, who was allowed to take the news of this defeat back.

Following the Norman slaughter at the hands of the Northumbrians, resistance to Norman rule spread throughout Northern England, including a similar uprising in York.[24] William The Conqueror subsequently (and successfully) attempted to halt the northern rebellions by unleashing the notorious Harrying of the North (1069–1070).[25] Because William's main focus during the harrying was on Yorkshire,[24] County Durham was largely spared the Harrying.[26] The best remains of the Norman period include Durham Cathedral and Durham Castle, and several parish churches, such as St Laurence Church in Pittington. The Early English period has left the eastern portion of the cathedral, the churches of Darlington, Hartlepool, and St Andrew, Auckland, Sedgefield, and portions of a few other churches.

11th to 15th centuries

Until the 15th century, the most important administrative officer in the Palatinate was the steward. Other officers included the sheriff, the coroners, the Chamberlain and the chancellor. The palatine exchequer originated in the 12th century. The palatine assembly represented the whole county, and dealt chiefly with fiscal questions. The bishop's council, consisting of the clergy, the sheriff and the barons, regulated judicial affairs, and later produced the Chancery and the courts of Admiralty and Marshalsea.

_(33802921566).jpg)

The prior of Durham ranked first among the bishop's barons. He had his own court, and almost exclusive jurisdiction over his men. A UNESCO site describes the role of the Prince-Bishops in Durham, the "buffer state between England and Scotland":[27]

From 1075, the Bishop of Durham became a Prince-Bishop, with the right to raise an army, mint his own coins, and levy taxes. As long as he remained loyal to the king of England, he could govern as a virtually autonomous ruler, reaping the revenue from his territory, but also remaining mindful of his role of protecting England’s northern frontier.

A report states that the Bishops also had the authority to appoint judges and barons and to offer pardons.[28]

There were ten palatinate barons in the 12th century, most importantly the Hyltons of Hylton Castle, the Bulmers of Brancepeth, the Conyers of Sockburne, the Hansards of Evenwood, and the Lumleys of Lumley Castle. The Nevilles owned large estates in the county. John Neville, 3rd Baron Neville de Raby rebuilt Raby Castle, their principal seat, in 1377.

Edward I's quo warranto proceedings of 1293 showed twelve lords enjoying more or less extensive franchises under the bishop. The repeated efforts of the Crown to check the powers of the palatinate bishops culminated in 1536 in the Act of Resumption, which deprived the bishop of the power to pardon offences against the law or to appoint judicial officers. Moreover, indictments and legal processes were in future to run in the name of the king, and offences to be described as against the peace of the king, rather than that of the bishop. In 1596 restrictions were imposed on the powers of the chancery, and in 1646 the palatinate was formally abolished. It was revived, however, after the Restoration, and continued with much the same power until 5 July 1836, when the Durham (County Palatine) Act 1836 provided that the palatine jurisdiction should in future be vested in the Crown.[29][30]

15th century to the modern era

During the 15th-century Wars of the Roses, Henry VI passed through Durham. On the outbreak of the Great Rebellion in 1642 Durham inclined to support the cause of the Parliament, and in 1640 the high sheriff of the palatinate guaranteed to supply the Scottish army with provisions during their stay in the county. In 1642 the Earl of Newcastle formed the western counties into an association for the King's service, but in 1644 the palatinate was again overrun by a Scottish army, and after the Battle of Marston Moor (2 July 1644) fell entirely into the hands of the parliament.

In 1614 a bill was introduced in parliament for securing representation to the county and city of Durham and the borough of Barnard Castle. The bishop strongly opposed the proposal as an infringement of his palatinate rights, and the county was first summoned to return members to parliament in 1654. After the Restoration of 1660 the county and city returned two members each. In the wake of the Reform Act of 1832 the county returned two members for two divisions, and the boroughs of Gateshead, South Shields and Sunderland acquired representation. The bishops lost their secular powers in 1836.[31] The boroughs of Darlington, Stockton and Hartlepool returned one member each from 1868 until the Redistribution Act of 1885.

'Durham Castle and Cathedral' is a designated UNESCO World Heritage Site.[32] Other attractions in the County include; Auckland Castle, North of England Lead Mining Museum and Beamish Museum. [33]

Modern local government

The Municipal Corporations Act 1835 reformed the municipal boroughs of Durham, Stockton on Tees and Sunderland. In 1875, Jarrow was incorporated as a municipal borough,[34] as was West Hartlepool in 1887.[35] At a county level, the Local Government Act 1888 reorganised local government throughout England and Wales.[36] Most of the county came under control of the newly-formed Durham County Council in an area known as an administrative county. Not included were the county boroughs of Gateshead, South Shields and Sunderland. However, for purposes other than local government, the administrative county of Durham and the county boroughs continued to form a single county to which the Crown appointed a Lord Lieutenant of Durham.

Over its existence, the administrative county lost territory, both to the existing county boroughs, and because two municipal boroughs became county boroughs: West Hartlepool in 1902[35] and Darlington in 1915.[37] The county boundary with the North Riding of Yorkshire was adjusted in 1967: that part of the town of Barnard Castle historically in Yorkshire was added to County Durham,[38] while the administrative county ceded the portion of the Borough of Stockton-on-Tees in Durham to the North Riding.[39] In 1968, following the recommendation of the Local Government Commission, Billingham was transferred to the county borough of Teesside, in the North Riding.[40] In 1971, the population of the county—including all associated county boroughs (an area of 2,570 km2 (990 sq mi)[23])—was 1,409,633, with a population outside the county boroughs of 814,396.[41]

In 1974, the Local Government Act 1972 abolished the administrative county and the county boroughs, reconstituting County Durham as a non-metropolitan county.[36][42] The reconstituted County Durham lost territory[43] to the north-east (around Gateshead, South Shields and Sunderland) to Tyne and Wear[44][45] and to the south-east (around Hartlepool) to Cleveland.[44][45] At the same time it gained the former area of Startforth Rural District from the North Riding of Yorkshire.[46] The area of the Lord Lieutenancy of Durham was also adjusted by the Act to coincide with the non-metropolitan county[47] (which occupied 3,019 km2 (1,166 sq mi) in 1981).[23]

In 1996, as part of the 1990s UK local government reform, Cleveland was abolished[48] and its districts were reconstituted as unitary authorities.[49] Hartlepool and Stockton-on-Tees (north of the River Tees) were returned to Durham for the purposes of Lord Lieutenancy. The change in area for Lord Lieutenancy purposes to reflect the abolition of Cleveland was confirmed by the Lieutenancies Act 1997.[3] Cleveland was adopted as a postal county in 1974 and by the time of its abolition, the Royal Mail had abandoned the use of postal counties altogether.[50] Since 1996 the use of a county address line is permitted but not mandatory and can be however a writer wishes.[50]

In 1997 Darlington became a unitary authority and was separated from the shire county.

As part of the 2009 structural changes to local government in England initiated by the Department for Communities and Local Government,[51] the seven district councils within the County Council area were abolished. The County Council assumed their functions and became a unitary authority. The changes came into effect on 1 April 2009.[5]

Modern national government

Tourism

Bishop Auckland

An October 2019 article in The Guardian referred to Bishop Auckland as a "rundown town ... since the closure of the mines" but predicted that the re-opening of Auckland Castle would transform the area into a "leading tourist destination".[52] After renovations by the Auckland Project, the castle re-opened on 2 November 2019, operated by the Auckland Castle Trust, started by the owner of the castle, Jonathan Ruffer. In 2012 Ruffer had purchased the property and all of its contents, including the artwork, with works by Francisco de Zurbarán.[53][54][55]

Other projects in the town include the Mining Art Gallery, which opened in 2017 (thanks to support provided to the Castle Trust by Bishop Auckland and Shildon AAP and Durham County Council),[56] a viewing tower, an open-air theatre show (Kynren) depicting "An Epic Tale of England", and the Bishop Trevor Gallery at the Castle (which started displaying the National Gallery's "Masterpiece" touring exhibit in October 2019). In a few years, other attractions were expected to open at or near the Castle: a display of Spanish art, a Faith Museum, a site that will feature the works of Francisco de Zurbarán, a boutique hotel and two additional restaurants.

Reports suggest that the revival of the area, dubbed "the Auckland Project", will eventually cost a total of about £150m.[57][58] According to The Guardian,[59]

"The aim is to make the town – the heart of the abandoned Durham coalfields – a tourist destination that holds people for a day or two rather than just a couple of hours. The scheme will create hundreds of entry-level jobs in a county that suffers high unemployment and has some of the most deprived areas in northern Europe".

A Financial Times report in early November 2019 stated that "Kynren [theatre] has attracted 250,000 people and the Auckland Project, even with the castle closed, welcomed 35,500 visitors in the past year" to this community.[60]

A September 2019 report identified Bishop Auckland as one of the towns designated to receive up to £25 million in funding from a new Towns Fund intended "to improve industrial areas that have not benefitted from economic growth in the same way as more prosperous areas". Durham County Council's Cabinet member for economic regeneration said that the funds would help the partners in Bishop Auckland to regenerate the town center area.[61]

Geography

Geology

County Durham is underlain by Carboniferous rocks in the west. Permian and Triassic strata overlie these older rocks in the east. These sedimentary sequences have been cut by igneous dykes and sills.

Climate

| County Durham | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The following climate figures were gathered at the Durham weather station between 1971 and 2000.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Green belt

County Durham contains a small area of green belt in the north of the county, surrounding primarily the city of Durham, Chester-le-Street and other communities along the shared county border with Tyne and Wear, to afford a protection from the Wearside conurbation. There is a smaller portion of belt separating Urpeth, Ouston, Pelton, and Perkinsville from Birtley in Tyne and Wear. A further small segment by the coast separates Seaham from the Sunderland settlements of Beckwith Green and Ryhope. It was first drawn up in the 1990s.[67]

North Pennines

The county contains a sizeable area of the North Pennines, designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, primarily west of Tow Law and Barnard Castle. The highest point (county top) of historic County Durham is the trig point (not the summit) of Burnhope Seat, height 746 metres (2,448 ft), between Weardale and Teesdale on the border with historic Cumberland in the far west of the county. The local government reorganisation of 1974 placed the higher Mickle Fell south of Teesdale (the county top of Yorkshire) within the administrative borders of Durham (where it remains within the ceremonial county), although it is not generally recognised as the highest point of Durham.

The two main dales of County Durham (Teesdale and Weardale) and the surrounding fells, many of which exceed 2,000 feet (610 m) in height, are excellent hillwalking country, although not nearly as popular as the nearby Yorkshire Dales and Lake District national parks. The scenery is rugged and remote, and the high fells have a landscape typical of the Pennines with extensive areas of tussock grass and blanket peat bog in the west, with heather moorland on the lower slopes descending to the east. Hamsterley Forest near Crook is a popular recreational area for local residents.

Biology

Birds

152 species of birds are recorded as breeding; however, not all are considered regular breeders.[68]

Demography

Population

The Office for National Statistics estimated in 2016 that the Durham County Council area had a population of 522,100, the Borough of Darlington a population of 105,600, the Borough of Hartlepool a population of 92,800, and the part of the Borough of Stockton-on-Tees in County Durham (the other part being in North Yorkshire) a population of 137,300[note 2]. This gives the total estimated population of the ceremonial county at 857,800.[69][70]

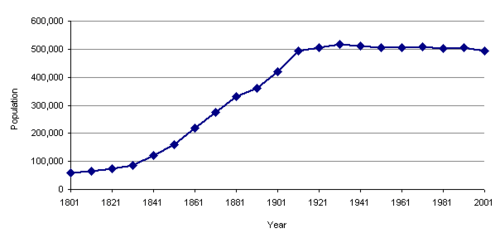

At the 2001 Census, Easington and Derwentside districts had the highest proportion (around 99%) in the county council area of resident population who were born in the UK.[71] 13.2% of the county council area's residents rate their health as not good, the highest proportion in England.[72] This table shows the historic population of the current remit of Durham County Council between 1801 and 2001.

| Year | Population | Year | Population | Year | Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1801 | 1871 | 1941 | |||||

| 1811 | |||||||

| 1821 | |||||||

| 1831 | |||||||

| 1841 | |||||||

| 1851 | |||||||

| 1861 | |||||||

| Source: A Vision of Britain through Time.[73] | |||||||

County Durham has 96.6% of residents come from a White British ethnic background, with other white groups making up a further 1.6% of the population. The largest non-white ethnic group is formed by those of Chinese descent, at around 1,600 people (0.3%) - most of these live in and around Durham itself, and many study at the university. Around 77% of the county's population are Christian, whilst 22% have no religion, and around 1% come from other religious communities. These figures exclude around 6% of the population who did not wish to state their religion.

Settlements

Since the Local Government Act 1972, some settlements within the historic county boundaries now lie within other administrative counties. These include:

| East Riding of Yorkshire | Howdenshire |

|---|---|

| North Yorkshire | Allertonshire |

| Northumberland | Bedlingtonshire, Islandshire (included Berwick-upon-Tweed) |

| Tyne and Wear | Birtley, Blaydon, Boldon, Felling, Gateshead, Hebburn, Hetton-le-Hole, Houghton-le-Spring, Jarrow, Ryton, South Shields, Sunderland, Washington, Whickham |

However a small number of settlements, such as Startforth, are now included within County Durham as opposed to Yorkshire.

Employment

The proportion of the population working in agriculture fell from around 6% in 1851 to 1% in 1951; currently less than 1% of the population work in agriculture.[23] There were 15,202 people employed in coal mining in 1841, rising to a peak of 157,837 in 1921.[23] As at 2001, Chester-le-Street district has the lowest number of available jobs per working-age resident (0.38%).[74]

Economy

Economic history

Legend

County Durham has long been associated with coal mining, from medieval times up to the late 20th century.[76] The Durham Coalfield covered a large area of the county, from Bishop Auckland, to Consett, to the River Tyne and below the North Sea, thereby providing a significant expanse of territory from which this rich mineral resource could be extracted.

King Stephen possessed a mine in Durham, which he granted to Bishop Pudsey, and in the same century colliers are mentioned at Coundon, Bishopwearmouth and Sedgefield. Cockfield Fell was one of the earliest Landsale collieries in Durham. Richard II granted to the inhabitants of Durham licence to export the produce of the mines, the majority being transported from the Port of Sunderland complex which was constructed in the 1850s.

Among other early industries, lead-mining was carried on in the western part of the county, and mustard was extensively cultivated. Gateshead had a considerable tanning trade and shipbuilding was undertaken at Sunderland, which became the largest shipbuilding town in the world – constructing a third of Britain's tonnage.

The county's modern-era economic history was facilitated significantly by the growth of the mining industry during the nineteenth century. At the industry's height, in the early 20th century, over 170,000 coal miners were employed,[76] and they mined 58,700,000 tons of coal in 1913 alone.[77] As a result, a large number of colliery villages were built throughout the county as the industrial revolution gathered pace.

The railway industry was also a major employer during the industrial revolution, with railways being built throughout the county, such as The Tanfield Railway, The Clarence Railway and The Stockton and Darlington Railway.[78] The growth of this industry occurred alongside the coal industry, as the railways provided a fast, efficient means to move coal from the mines to the ports and provided the fuel for the locomotives. The great railway pioneers Timothy Hackworth, Edward Pease, George Stephenson and Robert Stephenson were all actively involved with developing the railways in tandem with County Durham's coal mining industry.[79] Shildon and Darlington became thriving 'railway towns' and experienced significant growths in population and prosperity; before the railways, just over 100 people lived in Shildon but, by the 1890s, the town was home to around 8,000 people, with Shildon Shops employing almost 3000 people at its height.[80]

However, by the 1930s, the coal mining industry began to diminish and, by the mid-twentieth century, the pits were closing at an increasing rate.[81] In 1951, the Durham County Development Plan highlighted a number of colliery villages, such as Blackhouse, as 'Category D' settlements, in which future development would be prohibited, property would be acquired and demolished, and the population moved to new housing, such as that being built in Newton Aycliffe.[82] Likewise, the railway industry also began to decline, and was significantly brought to a fraction of its former self by the Beeching cuts in the 1960s. Darlington Works closed in 1966 and Shildon Shops followed suit in 1984. The county's last deep mines, at Easington, Vane Tempest, Wearmouth and Westoe, closed in 1993.

Boosting tourism

An October 2019 article in The Guardian referred to town of Bishop Auckland as a "rundown town ... since the closure of the mines" but predicted that the re-opening of Auckland Castle would transform the community into a "leading tourist destination".[83] The castle re-opened on 2 November 2019 after renovations by the Auckland Project, operated by the Auckland Castle Trust, started by the owner of the castle, Jonathan Ruffer.[84][85][86]

The interior had been fully restored, including the bishops' "palatial" apartments. The Faith Museum of world religion and a huge glass greenhouse were under construction.[87]

Other attractions already operating include the Mining Art Gallery which opened in 2017,[88] an open-air theatre, Kynren, depicting "An Epic Tale of England", and the Bishop Trevor Gallery at the Castle; the latter started displaying the National Gallery's Masterpiece touring exhibit in October 2019. In a few years, other attractions were expected to open at or near the Castle: a display of Spanish art, the Faith Museum (already being built), a site that will feature the works of Francisco de Zurbarán, a boutique hotel and two restaurants, in addition to the Bishop's Kitchen café. According to The Guardian,[89]

The aim is to make the town – the heart of the abandoned Durham coalfields – a tourist destination that holds people for a day or two rather than just a couple of hours. The scheme will create hundreds of entry-level jobs in a county that suffers high unemployment and has some of the most deprived areas in northern Europe

Economic output

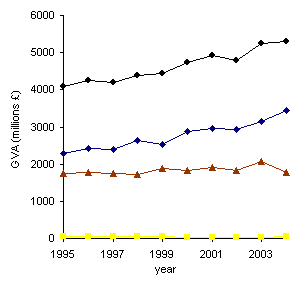

The chart and table summarise unadjusted gross value added (GVA) in millions of pounds sterling for County Durham across 3 industries at current basic prices from 1995 to 2004.

| Gross Value Added (GVA) (£m) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 2000 | 2004 | |

| Agriculture, hunting and forestry | 45 | 33 | 48 |

| Industry, including energy and construction | 1,751 | 1,827 | 1,784 |

| Service activities | 2,282 | 2,869 | 3,455 |

| Total | 4,078 | 4,729 | 5,288 |

| UK | 640,416 | 840,979 | 1,044,165 |

Post markings

Postal Rates from 1801 were charged depending on the distance from London. Durham was allocated the code 263 the approximate mileage from London. From about 1811, a datestamp appeared on letters showing the date the letter was posted. In 1844 a new system was introduced and Durham was allocated the code 267. This system was replaced in 1840 when the first postage stamps were introduced.

Culture

Mining and heavy industry

A substantial number of colliery villages were built throughout the county in the nineteenth century to house the growing workforce, which included large numbers of migrant workers from the rest of the UK.[76] Sometimes the migrants were brought in to augment the local workforce but, in other cases, they were brought in as strike breakers, or "blacklegs". Tens of thousands of people migrated to County Durham from Cornwall (partly due to their previous experience of tin mining) between 1815 and the outbreak of the First World War, so much so that the miners' cottages in east Durham called "Greenhill" were also known locally as "Cornwall", and Easington Colliery still has a Cornish Street.[90] Other migrants included people from Northumberland, Cumberland, South Wales, Scotland and Ireland.[91][92]Coal mining had a profound effect on trade unionism, public health and housing, as well as creating a related culture, language, folklore and sense of identity that still survives today.[77]

The migrants also were employed in the railway, ship building, iron, steel and roadworking industries, and the pattern of migration continued, to a lesser extent, up until the 1950s and 1960s. Gateshead was once home to the fourth-largest Irish settlement in England,[91] Consett's population was 22% Irish[93] and significant numbers of Irish people moved to Sunderland, resulting in the city hosting numerous events on St. Patrick's Day due to the Irish heritage.[94]

The culture of coal mining found expression in the Durham Miners' Gala, which was first held in 1871,[95] developed around the culture of trade unionism. Coal mining continued to decline and pits closed. The UK miners' strike of 1984/5 caused many miners across the county to strike. Today no deep-coal mines exist in the county and numbers attending the Miners' Gala decreased over the period between the end of the strike and the 21st century. However recent years have seen numbers significantly grow, and more banners return to the Gala each year as former colliery communities restore or replicate former banners to march at the Gala parade.[95][96]

Art

In 1930, the Spennymoor Settlement (otherwise known as the Pitman's Academy) opened. The settlement, initially funded by the Pilgrim Trust, aimed to encourage people to be neighbourly and participate in voluntary social service.[97] The settlement operated during the Great Depression, when unemployment was widespread and economic deprivation rife; Spennymoor was economically underprivileged. The settlement provided educational and social work, as well as hope; this included providing unemployed miners with on outlet for their creativity, a poor person's lawyer service, the town's first library and the Everyman Theatre. The output included paintings, sewing, socially-significant plays, woodwork and sculptures. Several members went on to win adult scholarships at Oxford University[97] when such a route would normally be closed to the underprivileged. Former members include artists Norman Cornish and Tom McGuinness, writer Sid Chaplin OBE and journalist Arnold Hadwin OBE. The Spennymoor Settlement at its home in the Everyman Theatre (Grade 2 listed) is still operating, administered by the current trustees, offering community events and activities, including Youth Theatre Group, an Art Group and various classes, as well as offering community accommodation facilities.

Several Durham miners have been able to turn their former mining careers into careers in art. For example, Tom Lamb, as well as the aforementioned Tom McGuinness and Norman Cornish. Their artworks depict scenes of life underground, from the streets in which they lived and of the people they loved; through them, we can see, understand and experience the mining culture of County Durham.

In 2017, The Mining Art Gallery opened in Bishop Auckland in a building that was once a bank.[98] Part of the Auckland Project, the gallery includes the work of artists from within County Durham and beyond, including such other North-Eastern mining artists as Robert Olley, as well as contributions from outside the region. It features three permanent areas and a temporary exhibition area; the gallery's Gemini Collection includes 420 pieces of mining art. [99] Much of the artwork was donated, by Dr Robert McManners and Gillian Wales, for example.[100]

In 2019, 100 years after his birth, a permanent tribute to the work of the artist Norman Stansfield Cornish MBE was opened within the Town Hall, and a Cornish Trail around the town was established to include areas of the town depicted in Cornish's artwork.

Music

As with neighbouring Northumberland, County Durham has a rich heritage of Northumbrian music, dating back from the Northumbrian Golden Age of the 7th and 8th centuries. Bede made references to harp-playing, and abundant archeological evidence has been found of wooden flutes, bone flutes, panpipes, wooden drums and lyres (a six-string form of harp).[13] North-East England has a distinctive folk music style that has drawn from many other regions, including southern Scotland, Ireland and the rest of northern England, that has endured stably since the 18th century.[101] Instruments played include, in common with most folk music styles, stringed instruments such as the guitar and fiddle, but also the Northumbrian smallpipe, which is played and promoted by people including the Northumbrian Pipers' Society throughout the North East, including County Durham, with the society having an active group in Sedgefield.[102] Contemporary folk musicians include Jez Lowe and Ged Foley.

In 2018, The Arts Council funded the Stories of Sanctuary project in the city of Durham. The project aims to assist people living in the city to share their stories about seeking sanctuary in the North East through photography, stories, poetry and music. The art is based on a history of sanctuary in Durham, from St Cuthbert's exile, through to the miners' strike of 1984, and to refugees escaping civil war in the Middle East. The music produced as part of the project includes contributions from singer-songwriter Sam Slatcher and viola player Raghad Haddad from the National Syrian Orchestra.[103]

Other notable performers/songwriters who were born or raised in the county include Paddy McAloon, Eric Boswell, Jeremy Spencer, Alan Clark, Martin Brammer, Robert Blamire, Thomas Allen, Zoe Birkett, John O'Neill, Karen Harding and Courtney Hadwin.

Flag

County Durham has its own flag, registered with the Flag Institute on 21 November 2013.[104]

Katie, Holly and James Moffatt designed the flag and entered their design into a competition launched by campaigner Andy Strangeway, who spoke of the flag as "free, public symbol for all to use, especially on 20th March each year, which is not only County Durham Day but also St Cuthbert’s birthday.”[105]

The flag consists of St Cuthbert's cross counterchanged with the county's blue and gold colours.

Education

Durham LEA has a comprehensive school system with 36 state secondary schools (not including sixth form colleges) and five independent schools (four in Durham and one in Barnard Castle). Easington district has the largest school population by year, and Teesdale the smallest with two schools. Only one school in Easington and Derwentside districts have sixth forms, with about half the schools in the other districts having sixth forms.

The University of Durham is based in Durham city and is sometimes held to be the third oldest university in England.[106]

Places of interest

| Key | |

| Abbey/Priory/Cathedral | |

| Accessible open space | |

| Amusement/Theme Park | |

| Castle | |

| Country Park | |

| English Heritage | |

| Forestry Commission | |

| Heritage railway | |

| Historic House | |

| Mosques | |

| Museum (free/not free) | |

| National Trust | |

| Theatre | |

| Zoo | |

- Apollo Pavilion, Peterlee, controversial piece of concrete art designed by Victor Pasmore in 1969.

- Auckland Castle, Bishop Auckland

- Barnard Castle

- Beamish Museum, in Stanley

.svg.png)

- Binchester Roman Fort

.svg.png)

- Bowes Museum, in Barnard Castle

.svg.png)

- Castle Eden, a castle with adjoining village, famous for the Castle Eden Brewery.

- Castle Eden Dene, Nature reserve with coal mining heritage.

- Causey Arch, near Stanley

- County Hall

- Crook Hall and Gardens

- Durham Cathedral and Castle, a World Heritage Site

- Durham Dales

- Durham Light Infantry Museum, Aykley Heads, Near Durham

.svg.png)

- Escomb Saxon Church, near Bishop Auckland

- Finchale Priory, near Durham city

- Hamsterley Forest

- Hardwick Hall Country Park

- High Force and Low Force waterfalls, on the River Tees

- Ireshopeburn – oldest Methodist chapel in the world to have held continuous services. Site of the 'Weardale Museum'

- Killhope Wheel, part of the North of England Lead Mining Museum in Weardale

.svg.png)

- Kynren, night show in Bishop Auckland, depicting British History.

- Longovicium Roman Fort, Lanchester – ruined auxiliary fort.

- North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers, Newcastle

- Oriental Museum, Durham City – Asian artefacts and information.

- Raby Castle, near Staindrop

- The Raby Hunt in Summerhouse, the only 2-Michelin Star restaurant in North East England.

- Seaham Hall

- Sedgefield – St Edmund's Church has notable Cosin woodwork. Home to Sedgefield Racecourse.

- Locomotion railway museum, in Shildon

- Spennymoor - Jubilee park

- Tanfield Railway, in Tanfield

- Ushaw College, Catholic Seminary of great religious heritage.

- Weardale Railway, at Stanhope, County Durham, Wolsingham and Bishop Auckland

See also

- List of Lord Lieutenants of Durham

- List of Deputy Lieutenants of Durham

- Custos Rotulorum of Durham – Keepers of the Rolls

- List of High Sheriffs of Durham

- County Durham (UK Parliament constituency) – Historical list of MPs for County Durham constituency

Notes

- The ceremonial county is formally named Durham – see Etymology.

- The total estimated population of the Borough of Stockton-on-Tees (195,700) less the populations of the electoral wards of Ingleby Barwick East, Ingleby Barwick West, Mandale and Victoria, Stainsby Hill, Village, and Yarm.

References

Citations

- "New High Sheriff sworn in at Durham Crown Court ceremony". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- North East Assembly – About North East England Archived 20 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- Lieutenancies Act 1997 Archived 19 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- Durham County Council – History and Heritage of County Durham Archived 20 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- "The County Durham (Structural Change) Order 2008". www.legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009.

- "The Local Government (Structural Changes) (Miscellaneous Amendments and Other Provision) Order 2009". legislation.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 3 March 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- "The County Durham (Structural Change) Order 2008". Office of Public Sector Information. 2008. Archived from the original on 23 April 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- Durham County Council – Districts of Durham map Archived 9 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- "The Durham (Borough of Darlington) (Structural Change) Order 1995". Office of Public Sector Information. 1995. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- "The Cleveland (Structural Change) Order 1995". Office of Public Sector Information. 1995. Archived from the original on 2 May 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- Durham Constabulary – Force Geography Archived 24 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- "Combined Fire Authority". Durham and Darlington Fire and Rescue Authority. 25 February 2009. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2009.

- Gething, Paul (2012). Northumbria: The Lost Kingdom. The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-9089-2.

- "Birth of Durham and Reign of Canute". englandsnortheast.co.uk.

- Scammell, Jean (1966). "The Origin and Limitations of the Liberty of Durham". The English Historical Review. 81 (320): 449–473. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXXI.CCCXX.449. JSTOR 561658.

- Warren, W. L. (1984). "The Myth of Norman Administrative Efficiency: The Prothero Lecture". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 34: 113–132. doi:10.2307/3679128. JSTOR 3679128.

- Fraser, C. M. (1956). "Edward I of England and the Regalian Franchise of Durham". Speculum. 31 (2): 329–342. doi:10.2307/2849417. JSTOR 2849417.

- Vision of Britain – Durham historic boundaries. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- "History of County Durham | Map and description for the county, A Vision of Britain through Time". Vision of Britain. University of Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- Vision of Britain – Islandshire Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine (historic map). Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- Vision of Britain – Norhamshire Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine (historic map). Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- Vision of Britain – Durham (Ancient): area Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007

- National Statistics – 200 years of the Census in... Durham Archived 3 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- Dodds (2005). Northumbria at War: War and Conflict in Northumberland and Durham (Battlefield Britain). Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-0-11-702037-5.

- "The Harrying of the North | History Today". www.historytoday.com.

- Douglas, D.C. William the Conqueror: The Norman Impact Upon England

- "The Prince Bishops of Durham". Durham World Heritage Site. 11 July 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Drummond Liddy, Christian (2008). The Bishopric of Durham in the Late Middle Ages. Boydell. p. 1. ISBN 978-1843833772.

- The Durham (County Palatine) Act 1836 (6 & 7 Will 4 c 19)

- The Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. His Majesty's Statute and Law Printers. 1836. p. 130.

bishop of durham temporal Powers by Palatine Act 1836.

- "The Bishops of Durham". Dicese of Durham. 11 July 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Durham Castle and Cathedral". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- "Top 5 Heritage Attractions in and around Durham". 25 February 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Vision of Britain – Jarrow MB Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- Vision of Britain – West Hartlepool MB/CB Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- Bryne, T. (1994). Local Government in Britain. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-026739-6.

- Vision of Britain – Darlington MB/CB Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- Vision of Britain – Yorkshire, North Riding Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- Vision of Britain – Stockton on Tees Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- Vision of Britain – Billingham UD Archived 29 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- UK Census, 1971

- Office for National Statistics (1999). Gazetteer of the old and new geographies of the United Kingdom. Office for National Statistics. ISBN 978-1-85774-298-5.

- Her Majesty's Stationery Office (1996). Aspects of Britain: Local Government. Stationery Office Books. ISBN 978-0-11-702037-5.

- Arnold-Baker, C., Local Government Act 1972, (1973)

- Young, F. (1991). Guide to Local Administrative Units of England: Northern England. Royal Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-86193-127-9.

- Durham County Council – About Us: Council Logo Archived 14 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- Elcock, H., Local Government, (1994)

- OPSI – Cleveland (Structural Change) Order 1995 Archived 2 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- OPSI – Cleveland (Further Provision) Order 1995 Archived 7 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- Royal Mail, Address Management Guide, (2004)

- Durham County Council – Local Government Review in County Durham Archived 14 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- "Auckland Castle in Durham to open to public after £12.4m restoration". The Guardian. 25 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "Zurbarán Paintings". The Auckland Project. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "Auckland Castle to re-open after multimillion-pound restoration". BBC. 11 September 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "Eat & shop". The Auckland Project. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "MINING ART GALLERY MOVING AHEAD". The Auckland Project. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- "Castle opening crowns £150m revival of Bishop Auckland". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Pearson, Harry (2 November 2019). "First look: a tour of the restored Auckland Castle". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- Pearson, Harry (2 November 2019). "First look: a tour of the restored Auckland Castle". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- "City philanthropist battles to transform 'left behind' UK town". Financial Times. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

-

"North East towns land £175m from Government fund". Trinity Mirror North East. 6 September 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

Seven North East towns have each been selected to receive up to £25m each as part of a Government initiative to provide a boost to economies that have been left behind.

Bishop Auckland, Blyth, Darlington, Hartlepool, Middlesbrough, Redcar and Thornaby have all been selected to receive cash from the new £3.6bn Towns Fund. - "Durham 1971–2000 averages". Met Office. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2007.

- "Durham climate information". Met Office. 1981–2010. Retrieved 11 August 2015.

- "Exceptional warmth, December 2015". Met Office. 27 January 2016. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- Kendon, Mike; McCarthy, Mark; Jevrejeva, Svetlana; Legg, Tim (2015). "State of the UK Climate 2015" (PDF). Met Office. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- "North East England Climate : Durham Weather". Durham Weather UK. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- "PLANNING AND HIGHWAYS COMMITTEE 21 NOVEMBER 2012 THE COUNTY DURHAM PLAN, LOCAL PLAN PREFERED [sic] OPTIONS". www.sunderland.gov.uk.

- Bowey, K. and Newsome, M. (Ed) 2012. The Birds of Durham. Durham Bird Club. ISBN 978-1-874701-03-3

- "Population Estimates for UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, Mid-2016". Office for National Statistics. 22 June 2017. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "Ward Level Mid-Year Population Estimates, Mid-2016". Office for National Statistics. 26 October 2017. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- National Statistics – Census 2001 – Ethnicity and religion in England and Wales Archived 11 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- National Statistics – Health Of The Nation Archived 11 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- A Vision of Britain through time. "Durham: Total Population". Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

- Hastings, D., Local area labour market statistical indicators incorporating the Annual Population Survey Archived 3 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine, National Statistics – Labour Market Trends, (2006). Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- "NUTS3 GVA (1995–2004) Data". Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 3 March 2005. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- "Coal Mining and Durham Collieries". www.durhamrecordoffice.org.uk. 28 November 2016.

- "About Coal Mining in County Durham". www.durhamintime.org.uk.

- "History of Railways in County Durham - Waggonways". sites.google.com.

- "Coal Mining in North East England". englandsnortheast.co.uk.

- "Life in the booming railway town". Locomotion.

- Pattison, Gary (2004). "Planning for decline: The 'D'‐village policy of County Durham, UK". Planning Perspectives. 19 (3): 311–332. doi:10.1080/02665430410001709804.

- "Category-D villages in County Durham - Waggonways". sites.google.com.

- "Auckland Castle in Durham to open to public after £12.4m restoration". The Guardian. 25 October 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "Zurbarán Paintings". The Auckland Project. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "Auckland Castle to re-open after multimillion-pound restoration". BBC News. 11 September 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "Eat & shop". The Auckland Project. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- "Hothouse towers: Auckland Castle's skyscraping revamp". The Guardian. 5 November 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "MINING ART GALLERY MOVING AHEAD". The Auckland Project. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- Pearson, Harry (2 November 2019). "First look: a tour of the restored Auckland Castle". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- "Coal Zoom | The Cornish in County Durham, England: How 19th Century Mining Migration Shaped the Region". www.coalzoom.com.

- "Irish migration to North East England | Co-Curate". co-curate.ncl.ac.uk.

- Griffiths (2011). A dictionary of North East dialect (Third ed.). Northumbria Press. ISBN 9781904794400.

- Harrison, Brian (7 November 2015). "Our Irish Immigrant Roots - Consett History".

- "Sunderland's Irish links celebrated on St Patrick's Day". Sunderlandecho.com. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- Miner's Advice – Moving on seamlessly... Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- Heritage Lottery Fund – Durham Miners' Gala Archived 28 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 December 2007.

- "History". www.spennymoorsettlement.co.uk.

- Kennedy, Maev (11 September 2017). "Museum of miners' art to open as part of Bishop Auckland culture drive". The Guardian – via www.theguardian.com.

- "Mining Art Gallery". Auckland Project. 11 July 2019. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "Mining Art Gallery opens doors in Bishop Auckland". Auckland Project. 11 July 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- S. Broughton, M. Ellingham, R. Trillo, O. Duane, V. Dowell, World Music: The Rough Guide (Rough Guides, 1999), p. 67.

- "Northumbrian Pipers Society - NPS Cleveland Branch". www.northumbrianpipers.org.uk.

- https://storiesofsanctuary.co.uk/

- "County Durham".

- "County Durham Flag". 21 November 2013.

- "About Durham University : Our history and values – Durham University". dur.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

Sources

Further reading

- Samuel Tymms (1837). "Durham". Northern Circuit. The Family Topographer: Being a Compendious Account of the ... Counties of England. 6. London: J.B. Nichols and Son. OCLC 2127940.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to County Durham. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about County Durham. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for County Durham. |

- County Durham at Curlie

- Durham County Council

- Hotels in Co Durham

- One North East guides & brochures

- Guided Walks Programme from Durham County Councill

- Visit County Durham

- The North East Forum

- Images of Durham at the English Heritage Archive

- "Durham", Historical Directories, UK: University of Leicester