Heptarchy

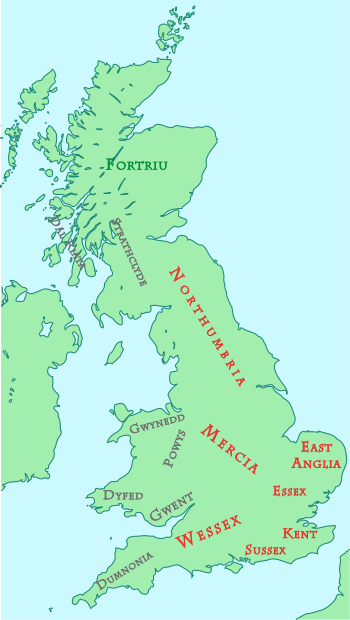

The Heptarchy (Old English: Seofonrīċe) is a collective name applied to the seven kingdoms of Anglo-Saxon England (sometimes referred to as petty kingdoms)[1] from the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain in the 5th century until their unification into the Kingdom of England in the early 10th century.

The term ‘Heptarchy’ (from the Greek ἑπταρχία heptarchia, from ἑπτά hepta ’seven’, ἀρχή arche ‘reign, rule’ and the suffix -ία -ia) alludes to the tradition that there were seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, usually enumerated as: East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Mercia, Northumbria, Sussex, and Wessex.

The historiographical tradition of the ‘seven kingdoms’ is medieval, first recorded by Henry of Huntingdon in his Historia Anglorum (12th century);[2] the term Heptarchy dates to the 16th century.

History

By convention, the Heptarchy period lasted from the end of Roman rule in Britain in the 5th century, until most of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms came under the overlordship of Egbert of Wessex in 829. This approximately 400-year period of European history is often referred to as the Early Middle Ages or, more controversially, as the Dark Ages. Although heptarchy suggests the existence of seven kingdoms, the term is just used as a label of convenience and does not imply the existence of a clear-cut or stable group of seven kingdoms. The number of kingdoms and sub-kingdoms fluctuated rapidly as kings contended for supremacy.[3]

In the late 6th century, the king of Kent was a prominent lord in the south. In the 7th century, the rulers of Northumbria and Wessex were powerful. In the 8th century, Mercia achieved hegemony over the other surviving kingdoms, particularly with "Offa the Great". Yet, as late as the reigns of Eadwig and Edgar (955–75), it was still possible to speak of separate kingdoms within the English population.

Alongside the seven kingdoms, a number of other political divisions also existed, such as the kingdoms (or sub-kingdoms) of: Bernicia and Deira within Northumbria; Lindsey in present-day Lincolnshire; the Hwicce in the southwest Midlands; the Magonsæte or Magonset, a sub-kingdom of Mercia in what is now Herefordshire; the Wihtwara, a Jutish kingdom on the Isle of Wight, originally as important as the Cantwara of Kent; the Middle Angles, a group of tribes based around modern Leicestershire, later conquered by the Mercians; the Hæstingas (around the town of Hastings in Sussex); and the Gewisse, a Saxon tribe in what is now southern Hampshire that later developed into the kingdom of Wessex.

The decline of the Heptarchy and the eventual emergence of the kingdom of England was a drawn-out process, taking place over the course of the 9th to 10th centuries. Over the course of the 9th century, the Danish enclave at York expanded into the Danelaw, with about half of England under Danish rule. The English unification under Alfred the Great was a reaction to the threat by the common enemy. In 886, Alfred retook London, and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that "all of the English people (all Angelcyn) not subject to the Danes submitted themselves to King Alfred."[4]

The unification of the kingdom of England was complete only in the 10th century, following the expulsion of Eric Bloodaxe as king of Northumbria. Æthelstan was the first to be King of all England.[5]

List of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms

The four main kingdoms in Anglo-Saxon England were:

- East Anglia

- Mercia

- Northumbria, including sub-kingdoms Bernicia and Deira

- Wessex

The other main kingdoms, which were conquered by others entirely at some point in their history, before the unification of England, are:

Other minor kingdoms and territories include:

- Deira

- Dumnonia (only annexed to Wessex at a later date, and a Cornish kingdom)

- Haestingas

- The Hwicce

- Kingdom of the Iclingas, a precursor state to Mercia

- Lindsey

- Magonsæte

- The Meonwara, a Jutish tribe in Hampshire

- Middle Angles

- Middle Saxons

- Pecsæte

- Surrey

- Tomsæte

- Wreocensæte

- Wihtwara

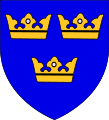

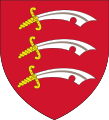

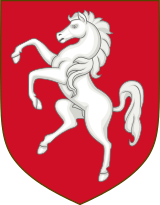

Attributed arms

Arms were attributed to the kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon heptarchy from the 12th or 13th century onward, with the development of heraldry.

The Kingdom of Essex, for instance, was assigned a red shield with three notched swords (or "seaxes"). This coat was used by the counties of Essex and Middlesex until 1910, when the Middlesex County Council applied for a formal grant from the College of Arms (The Times, 1910). Middlesex was granted a red shield with three notched swords and a "Saxon Crown". Essex County Council was granted the arms without the crown in 1932.

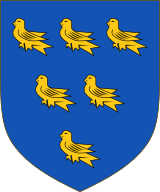

Kingdom of East Anglia

Kingdom of East Anglia Kingdom of Essex

Kingdom of Essex Kingdom of Kent (White horse of Kent)

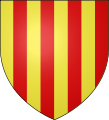

Kingdom of Kent (White horse of Kent) Kingdom of Mercia (Flag of Mercia)

Kingdom of Mercia (Flag of Mercia) Kingdom of Northumbria

Kingdom of Northumbria Kingdom of Sussex

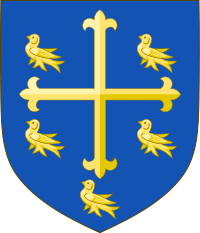

Kingdom of Sussex Kingdom of Wessex (Arms of Edward the Confessor)

Kingdom of Wessex (Arms of Edward the Confessor)

See also

- History of Anglo-Saxon England

- Cornovii (Cornish)

- Related terms: Bretwalda, High King for hegemons among kings

- Compare: Tetrarchy

References

- John Hines (2003). "Cultural Change and Social Organisation in Early Anglo-Saxon England". In Ausenda, Giorgio (ed.). After Empire: Towards an Ethnology of Europe's Barbarians. Boydell & Brewer. p. 82. ISBN 9780851158532.

- Historia Anglorum (History of the English People) - Google Books. Books.google.com.au. 1996. ISBN 9780198222248. Retrieved 2010-04-09.

- Norman F. Cantor, The Civilization of the Middle Ages1993:163f.

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Freely licensed version at Gutenberg Project. Note: This electronic edition is a collation of material from nine diverse extant versions of the Chronicle. It contains primarily the translation of Rev. James Ingram, as published in the Everyman edition. Asser's Life of King Alfred, ch. 83, trans. Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge, Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred & Other Contemporary Sources (Penguin Classics) (1984), pp. 97–8.

- Starkey, David (2004). The Monarchy of England: The beginnings. Chatto and Windus. p. 71. ISBN 9780701176785. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

Bibliography

- Westermann Großer Atlas zur Weltgeschichte

- Campbell, J. et al. The Anglo-Saxons. (Penguin, 1991)

- Sawyer, Peter Hayes. From Roman Britain to Norman England (Routledge, 2002).

- Stenton, F. M. Anglo-Saxon England, (3rd edition. Oxford U. P. 1971),

External links

- Monarchs of Britain, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ogdoad.force9.co.uk: The Burghal Hidage – Wessex's fortified burhs