Manchester United F.C.

Manchester United Football Club is a professional football club based in Old Trafford, Greater Manchester, England, that competes in the Premier League, the top flight of English football. Nicknamed "the Red Devils", the club was founded as Newton Heath LYR Football Club in 1878, changed its name to Manchester United in 1902 and moved to its current stadium, Old Trafford, in 1910.

| |||

| Full name | Manchester United Football Club | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | The Red Devils[1] | ||

| Short name | Man United/Utd United[2][3] | ||

| Founded | 1878, as Newton Heath LYR F.C. 1902, as Manchester United F.C. | ||

| Ground | Old Trafford | ||

| Capacity | 74,879[4] | ||

| Owner | Manchester United plc (NYSE: MANU) | ||

| Co-chairmen | Joel and Avram Glazer | ||

| Manager | Ole Gunnar Solskjær | ||

| League | Premier League | ||

| 2019–20 | Premier League, 3rd of 20 | ||

| Website | Club website | ||

|

| |||

Manchester United have won more trophies than any other club in English football,[5][6] with a record 20 League titles, 12 FA Cups, five League Cups and a record 21 FA Community Shields. United have also won three UEFA Champions Leagues, one UEFA Europa League, one UEFA Cup Winners' Cup, one UEFA Super Cup, one Intercontinental Cup and one FIFA Club World Cup. In 1998–99, the club became the first in the history of English football to achieve the continental European treble.[7] By winning the UEFA Europa League in 2016–17, they became one of five clubs to have won all three main UEFA club competitions.

The 1958 Munich air disaster claimed the lives of eight players. In 1968, under the management of Matt Busby, Manchester United became the first English football club to win the European Cup. Alex Ferguson won 38 trophies as manager, including 13 Premier League titles, 5 FA Cups and 2 UEFA Champions Leagues, between 1986 and 2013,[8][9][10] when he announced his retirement.

Manchester United was the highest-earning football club in the world for 2016–17, with an annual revenue of €676.3 million,[11] and the world's third most valuable football club in 2019, valued at £3.15 billion ($3.81 billion).[12] As of June 2015, it is the world's most valuable football brand, estimated to be worth $1.2 billion.[13][14] After being floated on the London Stock Exchange in 1991, the club was purchased by Malcolm Glazer in May 2005 in a deal valuing the club at almost £800 million, after which the company was taken private again, before going public once more in August 2012, when they made an initial public offering on the New York Stock Exchange. Manchester United is one of the most widely supported football clubs in the world,[15][16] and has rivalries with Liverpool, Manchester City, Arsenal and Leeds United.

History

Early years (1878–1945)

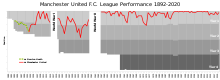

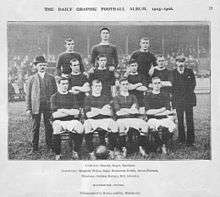

Manchester United was formed in 1878 as Newton Heath LYR Football Club by the Carriage and Wagon department of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (LYR) depot at Newton Heath.[17] The team initially played games against other departments and railway companies, but on 20 November 1880, they competed in their first recorded match; wearing the colours of the railway company – green and gold – they were defeated 6–0 by Bolton Wanderers' reserve team.[18] By 1888, the club had become a founding member of The Combination, a regional football league. Following the league's dissolution after only one season, Newton Heath joined the newly formed Football Alliance, which ran for three seasons before being merged with The Football League. This resulted in the club starting the 1892–93 season in the First Division, by which time it had become independent of the railway company and dropped the "LYR" from its name.[17] After two seasons, the club was relegated to the Second Division.[17]

In January 1902, with debts of £2,670 – equivalent to £290,000 in 2020[nb 1] – the club was served with a winding-up order.[19] Captain Harry Stafford found four local businessmen, including John Henry Davies (who became club president), each willing to invest £500 in return for a direct interest in running the club and who subsequently changed the name;[20] on 24 April 1902, Manchester United was officially born.[21][nb 2] Under Ernest Mangnall, who assumed managerial duties in 1903, the team finished as Second Division runners-up in 1906 and secured promotion to the First Division, which they won in 1908 – the club's first league title. The following season began with victory in the first ever Charity Shield[22] and ended with the club's first FA Cup title. Manchester United won the First Division for the second time in 1911, but at the end of the following season, Mangnall left the club to join Manchester City.[23]

In 1922, three years after the resumption of football following the First World War, the club was relegated to the Second Division, where it remained until regaining promotion in 1925. Relegated again in 1931, Manchester United became a yo-yo club, achieving its all-time lowest position of 20th place in the Second Division in 1934. Following the death of principal benefactor John Henry Davies in October 1927, the club's finances deteriorated to the extent that Manchester United would likely have gone bankrupt had it not been for James W. Gibson, who, in December 1931, invested £2,000 and assumed control of the club.[24] In the 1938–39 season, the last year of football before the Second World War, the club finished 14th in the First Division.[24]

Busby years (1945–1969)

In October 1945, the impending resumption of football led to the managerial appointment of Matt Busby, who demanded an unprecedented level of control over team selection, player transfers and training sessions.[25] Busby led the team to second-place league finishes in 1947, 1948 and 1949, and to FA Cup victory in 1948. In 1952, the club won the First Division, its first league title for 41 years.[26] They then won back-to-back league titles in 1956 and 1957; the squad, who had an average age of 22, were nicknamed "the Busby Babes" by the media, a testament to Busby's faith in his youth players.[27] In 1957, Manchester United became the first English team to compete in the European Cup, despite objections from The Football League, who had denied Chelsea the same opportunity the previous season.[28] En route to the semi-final, which they lost to Real Madrid, the team recorded a 10–0 victory over Belgian champions Anderlecht, which remains the club's biggest victory on record.[29]

The following season, on the way home from a European Cup quarter-final victory against Red Star Belgrade, the aircraft carrying the Manchester United players, officials and journalists crashed while attempting to take off after refuelling in Munich, Germany. The Munich air disaster of 6 February 1958 claimed 23 lives, including those of eight players – Geoff Bent, Roger Byrne, Eddie Colman, Duncan Edwards, Mark Jones, David Pegg, Tommy Taylor and Billy Whelan – and injured several more.[30][31]

Assistant manager Jimmy Murphy took over as manager while Busby recovered from his injuries and the club's makeshift side reached the FA Cup final, which they lost to Bolton Wanderers. In recognition of the team's tragedy, UEFA invited the club to compete in the 1958–59 European Cup alongside eventual League champions Wolverhampton Wanderers. Despite approval from The Football Association, The Football League determined that the club should not enter the competition, since it had not qualified.[32][33] Busby rebuilt the team through the 1960s by signing players such as Denis Law and Pat Crerand, who combined with the next generation of youth players – including George Best – to win the FA Cup in 1963. The following season, they finished second in the league, then won the title in 1965 and 1967. In 1968, Manchester United became the first English (and second British) club to win the European Cup, beating Benfica 4–1 in the final[34] with a team that contained three European Footballers of the Year: Bobby Charlton, Denis Law and George Best.[35] They then represented Europe in the 1968 Intercontinental Cup against Estudiantes of Argentina, but lost the tie after losing the first leg in Buenos Aires, before a 1–1 draw at Old Trafford three weeks later. Busby resigned as manager in 1969 before being replaced by the reserve team coach, former Manchester United player Wilf McGuinness.[36]

1969–1986

Following an eighth-place finish in the 1969–70 season and a poor start to the 1970–71 season, Busby was persuaded to temporarily resume managerial duties, and McGuinness returned to his position as reserve team coach. In June 1971, Frank O'Farrell was appointed as manager, but lasted less than 18 months before being replaced by Tommy Docherty in December 1972.[38] Docherty saved Manchester United from relegation that season, only to see them relegated in 1974; by that time the trio of Best, Law, and Charlton had left the club.[34] The team won promotion at the first attempt and reached the FA Cup final in 1976, but were beaten by Southampton. They reached the final again in 1977, beating Liverpool 2–1. Docherty was dismissed shortly afterwards, following the revelation of his affair with the club physiotherapist's wife.[36][39]

Dave Sexton replaced Docherty as manager in the summer of 1977. Despite major signings, including Joe Jordan, Gordon McQueen, Gary Bailey, and Ray Wilkins, the team failed to achieve any significant results; they finished in the top two in 1979–80 and lost to Arsenal in the 1979 FA Cup Final. Sexton was dismissed in 1981, even though the team won the last seven games under his direction.[40] He was replaced by Ron Atkinson, who immediately broke the British record transfer fee to sign Bryan Robson from West Bromwich Albion. Under Atkinson, Manchester United won the FA Cup twice in three years – in 1983 and 1985. In 1985–86, after 13 wins and two draws in its first 15 matches, the club was favourite to win the league, but finished in fourth place. The following season, with the club in danger of relegation by November, Atkinson was dismissed.[41]

Ferguson years (1986–2013)

Alex Ferguson and his assistant Archie Knox arrived from Aberdeen on the day of Atkinson's dismissal,[42] and guided the club to an 11th-place finish in the league.[43] Despite a second-place finish in 1987–88, the club was back in 11th place the following season.[44] Reportedly on the verge of being dismissed, victory over Crystal Palace in the 1990 FA Cup Final replay (after a 3–3 draw) saved Ferguson's career.[45][46] The following season, Manchester United claimed its first Cup Winners' Cup title and competed in the 1991 UEFA Super Cup, beating European Cup holders Red Star Belgrade 1–0 in the final at Old Trafford. A second consecutive League Cup final appearance followed in 1992, in which the team beat Nottingham Forest 1–0 at Wembley.[41] In 1993, the club won its first league title since 1967, and a year later, for the first time since 1957, it won a second consecutive title – alongside the FA Cup – to complete the first "Double" in the club's history.[41] United then became the first English club to do the Double twice when they won both competitions again in 1995–96,[47] before retaining the league title once more in 1996–97 with a game to spare.[48]

_(262769292).jpg)

In the 1998–99 season, Manchester United became the first team to win the Premier League, FA Cup and UEFA Champions League – "The Treble" – in the same season.[49] Losing 1–0 going into injury time in the 1999 UEFA Champions League Final, Teddy Sheringham and Ole Gunnar Solskjær scored late goals to claim a dramatic victory over Bayern Munich, in what is considered one of the greatest comebacks of all time.[50] The club also won the Intercontinental Cup after beating Palmeiras 1–0 in Tokyo.[51] Ferguson was subsequently knighted for his services to football.[52]

Manchester United won the league again in the 1999–2000 and 2000–01 seasons. The team finished third in 2001–02, before regaining the title in 2002–03.[54] They won the 2003–04 FA Cup, beating Millwall 3–0 in the final at the Millennium Stadium in Cardiff to lift the trophy for a record 11th time.[55] In the 2005–06 season, Manchester United failed to qualify for the knockout phase of the UEFA Champions League for the first time in over a decade,[56] but recovered to secure a second-place league finish and victory over Wigan Athletic in the 2006 Football League Cup Final. The club regained the Premier League in the 2006–07 season, before completing the European double in 2007–08 with a 6–5 penalty shoot-out victory over Chelsea in the 2008 UEFA Champions League Final in Moscow to go with their 17th English league title. Ryan Giggs made a record 759th appearance for the club in that game, overtaking previous record holder Bobby Charlton.[57] In December 2008, the club won the 2008 FIFA Club World Cup and followed this with the 2008–09 Football League Cup, and its third successive Premier League title.[58][59] That summer, Cristiano Ronaldo was sold to Real Madrid for a world record £80 million.[60] In 2010, Manchester United defeated Aston Villa 2–1 at Wembley to retain the League Cup, its first successful defence of a knockout cup competition.[61]

After finishing as runner-up to Chelsea in the 2009–10 season, United achieved a record 19th league title in 2010–11, securing the championship with a 1–1 away draw against Blackburn Rovers on 14 May 2011.[62] This was extended to 20 league titles in 2012–13, securing the championship with a 3–0 home win against Aston Villa on 22 April 2013.[63]

2013–present

On 8 May 2013, Ferguson announced that he was to retire as manager at the end of the football season, but would remain at the club as a director and club ambassador.[64][65] The club announced the next day that Everton manager David Moyes would replace him from 1 July, having signed a six-year contract.[66][67][68] Ryan Giggs took over as interim player-manager 10 months later, on 22 April 2014, when Moyes was sacked after a poor season in which the club failed to defend their Premier League title and failed to qualify for the UEFA Champions League for the first time since 1995–96.[69] They also failed to qualify for the Europa League, meaning that it was the first time Manchester United had not qualified for a European competition since 1990.[70] On 19 May 2014, it was confirmed that Louis van Gaal would replace Moyes as Manchester United manager on a three-year deal, with Giggs as his assistant.[71] Malcolm Glazer, the patriarch of the Glazer family that owns the club, died on 28 May 2014.[72]

Although Van Gaal's first season saw United once again qualify for the Champions League through a fourth-place finish in the Premier League, his second season saw United go out of the same tournament in the group stage.[73] United also fell behind in the title race for the third consecutive season, finishing in 5th place, in spite of several expensive signings during Van Gaal's tenure. However, that same season, Manchester United won the FA Cup for a 12th time, this being their first trophy won since 2013.[74] Despite this victory, Van Gaal was sacked as manager just two days later,[75] with José Mourinho appointed in his place on 27 May, signing a three-year contract.[76] That season, United finished in sixth place while winning the EFL Cup for the fifth time and the Europa League for the first time, as well as the FA Community Shield for a record 21st time in Mourinho's first competitive match in charge.[77] Despite not finishing in the top four, United qualified for the Champions League through their Europa League win. Wayne Rooney scored his 250th goal with United, surpassing Sir Bobby Charlton as United's all-time top scorer, before leaving the club at the end of the season to return to Everton. The following season, United finished second in the league – their highest finish since 2013 but still 19 points behind rivals Manchester City. Mourinho also guided the club to their 19th FA Cup final, only to lose to Chelsea 1–0. On 18 December 2018, with United in sixth place in the Premier League table, 19 points behind leaders Liverpool and 11 points outside the Champions League places, Mourinho was sacked by the club after 144 games in charge. The following day, former United striker Ole Gunnar Solskjær was appointed caretaker manager until the end of the season. [78] On 28 March 2019, following an impressive run of 14 wins from his first 19 matches in charge, including knocking Paris Saint-Germain out of the Champions League after losing the first leg 2–0, Solskjær was appointed permanent manager on a three-year deal.[79]

Crest and colours

The club crest is derived from the Manchester City Council coat of arms, although all that remains of it on the current crest is the ship in full sail.[80] The devil stems from the club's nickname "The Red Devils"; it was included on club programmes and scarves in the 1960s, and incorporated into the club crest in 1970, although the crest was not included on the chest of the shirt until 1971.[80]

Newton Heath's uniform in 1879, four years before the club played its first competitive match, has been documented as 'white with blue cord'.[81] A photograph of the Newton Heath team, taken in 1892, is believed to show the players wearing red-and-white quartered jerseys and navy blue knickerbockers.[82] Between 1894 and 1896, the players wore green and gold jerseys[82] which were replaced in 1896 by white shirts, which were worn with navy blue shorts.[82]

After the name change in 1902, the club colours were changed to red shirts, white shorts, and black socks, which has become the standard Manchester United home kit.[82] Very few changes were made to the kit until 1922 when the club adopted white shirts bearing a deep red "V" around the neck, similar to the shirt worn in the 1909 FA Cup Final. They remained part of their home kits until 1927.[82] For a period in 1934, the cherry and white hooped change shirt became the home colours, but the following season the red shirt was recalled after the club's lowest ever league placing of 20th in the Second Division and the hooped shirt dropped back to being the change.[82] The black socks were changed to white from 1959 to 1965, where they were replaced with red socks up until 1971 with white used on occasion, when the club reverted to black. Black shorts and white socks are sometimes worn with the home strip, most often in away games, if there is a clash with the opponent's kit. For 2018–19, black shorts and red socks became the primary choice for the home kit.[83] Since 1997–98, white socks have been the preferred choice for European games, which are typically played on weeknights, to aid with player visibility.[84] The current home kit is a red shirt with the trademark Adidas three stripes in red on the shoulders, white shorts, and black socks.[85]

The Manchester United away strip has often been a white shirt, black shorts and white socks, but there have been several exceptions. These include an all-black strip with blue and gold trimmings between 1993 and 1995, the navy blue shirt with silver horizontal pinstripes worn during the 1999–2000 season,[86] and the 2011–12 away kit, which had a royal blue body and sleeves with hoops made of small midnight navy blue and black stripes, with black shorts and blue socks.[87] An all-grey away kit worn during the 1995–96 season was dropped after just five games; in its final outing against Southampton, Alex Ferguson instructed the team to change into the third kit during half-time. The reason for dropping it being that the players claimed to have trouble finding their teammates against the crowd, United failed to win a competitive game in the kit.[88] In 2001, to celebrate 100 years as "Manchester United", a reversible white and gold away kit was released, although the actual match day shirts were not reversible.[89]

The club's third kit is often all-blue; this was most recently the case during the 2014–15 season.[90] Exceptions include a green-and-gold halved shirt worn between 1992 and 1994, a blue-and-white striped shirt worn during the 1994–95 and 1995–96 seasons and once in 1996–97, an all-black kit worn during the Treble-winning 1998–99 season, and a white shirt with black-and-red horizontal pinstripes worn between 2003–04 and 2005–06.[91] From 2006–07 to 2013–14, the third kit was the previous season's away kit, albeit updated with the new club sponsor in 2006–07 and 2010–11, apart from 2008–09 when an all-blue kit was launched to mark the 40th anniversary of the 1967–68 European Cup success.[92]

Kit evolution

1879–1880, 1896–1902 |

1880–1887 |

1887–1893 |

1893–1894 |

1894–1896 |

1902–1920, 1921–1922, 1927–1934, 1934–1960, 1971–2018, 2019–present[EN] |

1920–1921, 1963–1971 |

1922–1927 |

1934 |

1960–1963 (1997–2018, 2019–present)[EU] |

2018–2019 |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manchester United F.C. kits. |

- Notes

Grounds

1878–1893: North Road

Newton Heath initially played on a field on North Road, close to the railway yard; the original capacity was about 12,000, but club officials deemed the facilities inadequate for a club hoping to join The Football League.[93] Some expansion took place in 1887, and in 1891, Newton Heath used its minimal financial reserves to purchase two grandstands, each able to hold 1,000 spectators.[94] Although attendances were not recorded for many of the earliest matches at North Road, the highest documented attendance was approximately 15,000 for a First Division match against Sunderland on 4 March 1893.[95] A similar attendance was also recorded for a friendly match against Gorton Villa on 5 September 1889.[96]

1893–1910: Bank Street

In June 1893, after the club was evicted from North Road by its owners, Manchester Deans and Canons, who felt it was inappropriate for the club to charge an entry fee to the ground, secretary A. H. Albut procured the use of the Bank Street ground in Clayton.[97] It initially had no stands, by the start of the 1893–94 season, two had been built; one spanning the full length of the pitch on one side and the other behind the goal at the "Bradford end". At the opposite end, the "Clayton end", the ground had been "built up, thousands thus being provided for".[97] Newton Heath's first league match at Bank Street was played against Burnley on 1 September 1893, when 10,000 people saw Alf Farman score a hat-trick, Newton Heath's only goals in a 3–2 win. The remaining stands were completed for the following league game against Nottingham Forest three weeks later.[97] In October 1895, before the visit of Manchester City, the club purchased a 2,000-capacity stand from the Broughton Rangers rugby league club, and put up another stand on the "reserved side" (as distinct from the "popular side"). However, weather restricted the attendance for the Manchester City match to just 12,000.[98]

When the Bank Street ground was temporarily closed by bailiffs in 1902, club captain Harry Stafford raised enough money to pay for the club's next away game at Bristol City and found a temporary ground at Harpurhey for the next reserves game against Padiham.[99] Following financial investment, new club president John Henry Davies paid £500 for the erection of a new 1,000-seat stand at Bank Street.[100] Within four years, the stadium had cover on all four sides, as well as the ability to hold approximately 50,000 spectators, some of whom could watch from the viewing gallery atop the Main Stand.[100]

1910–present: Old Trafford

Following Manchester United's first league title in 1908 and the FA Cup a year later, it was decided that Bank Street was too restrictive for Davies' ambition;[100] in February 1909, six weeks before the club's first FA Cup title, Old Trafford was named as the home of Manchester United, following the purchase of land for around £60,000. Architect Archibald Leitch was given a budget of £30,000 for construction; original plans called for seating capacity of 100,000, though budget constraints forced a revision to 77,000. The building was constructed by Messrs Brameld and Smith of Manchester. The stadium's record attendance was registered on 25 March 1939, when an FA Cup semi-final between Wolverhampton Wanderers and Grimsby Town drew 76,962 spectators.[101]

Bombing in the Second World War destroyed much of the stadium; the central tunnel in the South Stand was all that remained of that quarter. After the war, the club received compensation from the War Damage Commission in the amount of £22,278. While reconstruction took place, the team played its "home" games at Manchester City's Maine Road ground; Manchester United was charged £5,000 per year, plus a nominal percentage of gate receipts.[102] Later improvements included the addition of roofs, first to the Stretford End and then to the North and East Stands. The roofs were supported by pillars that obstructed many fans' views, and they were eventually replaced with a cantilevered structure. The Stretford End was the last stand to receive a cantilevered roof, completed in time for the 1993–94 season.[36] First used on 25 March 1957 and costing £40,000, four 180-foot (55 m) pylons were erected, each housing 54 individual floodlights. These were dismantled in 1987 and replaced by a lighting system embedded in the roof of each stand, which remains in use today.[103]

The Taylor Report's requirement for an all-seater stadium lowered capacity at Old Trafford to around 44,000 by 1993. In 1995, the North Stand was redeveloped into three tiers, restoring capacity to approximately 55,000. At the end of the 1998–99 season, second tiers were added to the East and West Stands, raising capacity to around 67,000, and between July 2005 and May 2006, 8,000 more seats were added via second tiers in the north-west and north-east quadrants. Part of the new seating was used for the first time on 26 March 2006, when an attendance of 69,070 became a new Premier League record.[104] The record was pushed steadily upwards before reaching its peak on 31 March 2007, when 76,098 spectators saw Manchester United beat Blackburn Rovers 4–1, with just 114 seats (0.15 per cent of the total capacity of 76,212) unoccupied.[105] In 2009, reorganisation of the seating resulted in a reduction of capacity by 255 to 75,957.[106][107] Manchester United has the second highest average attendance of European football clubs only behind Borussia Dortmund.[108][109][110]

Support

Manchester United is one of the most popular football clubs in the world, with one of the highest average home attendances in Europe.[111] The club states that its worldwide fan base includes more than 200 officially recognised branches of the Manchester United Supporters Club (MUSC), in at least 24 countries.[112] The club takes advantage of this support through its worldwide summer tours. Accountancy firm and sports industry consultants Deloitte estimate that Manchester United has 75 million fans worldwide.[15] The club has the third highest social media following in the world among sports teams (after Barcelona and Real Madrid), with over 72 million Facebook followers as of July 2020.[16][113] A 2014 study showed that Manchester United had the loudest fans in the Premier League.[114]

Supporters are represented by two independent bodies; the Independent Manchester United Supporters' Association (IMUSA), which maintains close links to the club through the MUFC Fans Forum,[115] and the Manchester United Supporters' Trust (MUST). After the Glazer family's takeover in 2005, a group of fans formed a splinter club, F.C. United of Manchester. The West Stand of Old Trafford – the "Stretford End" – is the home end and the traditional source of the club's most vocal support.[116]

Rivalries

Manchester United has rivalries with Arsenal, Leeds United, Liverpool, and Manchester City, against whom they contest the Manchester derby.[117][118]

The rivalry with Liverpool is rooted in competition between the cities during the Industrial Revolution when Manchester was famous for its textile industry while Liverpool was a major port.[119] The two clubs are the most successful English teams in both domestic and international competitions; and between them they have won 39 league titles, 9 European Cups, 4 UEFA Cups, 5 UEFA Super Cups, 19 FA Cups, 13 League Cups, 2 FIFA Club World Cups, 1 Intercontinental Cup and 36 FA Community Shields.[5][120][121] It is considered to be one of the biggest rivalries in the football world and is considered the most famous fixture in English football.[122][123][124][125][126] Former Manchester United manager Alex Ferguson said in 2002, "My greatest challenge was knocking Liverpool right off their fucking perch".[127]

The "Roses Rivalry" with Leeds stems from the Wars of the Roses, fought between the House of Lancaster and the House of York, with Manchester United representing Lancashire and Leeds representing Yorkshire.[128]

The rivalry with Arsenal arises from the numerous times the two teams, as well as managers Alex Ferguson and Arsène Wenger, have battled for the Premier League title. With 33 titles between them (20 for Manchester United, 13 for Arsenal) this fixture has become known as one of the finest Premier League match-ups in history.[129][130]

Global brand

Manchester United has been described as a global brand; a 2011 report by Brand Finance, valued the club's trademarks and associated intellectual property at £412 million – an increase of £39 million on the previous year, valuing it at £11 million more than the second best brand, Real Madrid – and gave the brand a strength rating of AAA (Extremely Strong).[131] In July 2012, Manchester United was ranked first by Forbes magazine in its list of the ten most valuable sports team brands, valuing the Manchester United brand at $2.23 billion.[132] The club is ranked third in the Deloitte Football Money League (behind Real Madrid and Barcelona).[133] In January 2013, the club became the first sports team in the world to be valued at $3 billion.[134] Forbes magazine valued the club at $3.3 billion – $1.2 billion higher than the next most valuable sports team.[134] They were overtaken by Real Madrid for the next four years, but Manchester United returned to the top of the Forbes list in June 2017, with a valuation of $3.689 billion.[135]

The core strength of Manchester United's global brand is often attributed to Matt Busby's rebuilding of the team and subsequent success following the Munich air disaster, which drew worldwide acclaim.[116] The "iconic" team included Bobby Charlton and Nobby Stiles (members of England's World Cup winning team), Denis Law and George Best. The attacking style of play adopted by this team (in contrast to the defensive-minded "catenaccio" approach favoured by the leading Italian teams of the era) "captured the imagination of the English footballing public".[136] Busby's team also became associated with the liberalisation of Western society during the 1960s; George Best, known as the "Fifth Beatle" for his iconic haircut, was the first footballer to significantly develop an off-the-field media profile.[136]

As the second English football club to float on the London Stock Exchange in 1991, the club raised significant capital, with which it further developed its commercial strategy. The club's focus on commercial and sporting success brought significant profits in an industry often characterised by chronic losses.[137] The strength of the Manchester United brand was bolstered by intense off-the-field media attention to individual players, most notably David Beckham (who quickly developed his own global brand). This attention often generates greater interest in on-the-field activities, and hence generates sponsorship opportunities – the value of which is driven by television exposure.[138] During his time with the club, Beckham's popularity across Asia was integral to the club's commercial success in that part of the world.[139]

Because higher league placement results in a greater share of television rights, success on the field generates greater income for the club. Since the inception of the Premier League, Manchester United has received the largest share of the revenue generated from the BSkyB broadcasting deal.[140] Manchester United has also consistently enjoyed the highest commercial income of any English club; in 2005–06, the club's commercial arm generated £51 million, compared to £42.5 million at Chelsea, £39.3 million at Liverpool, £34 million at Arsenal and £27.9 million at Newcastle United. A key sponsorship relationship was with sportswear company Nike, who managed the club's merchandising operation as part of a £303 million 13-year partnership between 2002 and 2015.[141] Through Manchester United Finance and the club's membership scheme, One United, those with an affinity for the club can purchase a range of branded goods and services. Additionally, Manchester United-branded media services – such as the club's dedicated television channel, MUTV – have allowed the club to expand its fan base to those beyond the reach of its Old Trafford stadium.[15]

Sponsorship

| Period | Kit manufacturer | Shirt sponsor (chest) | Shirt sponsor (sleeve) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1945–1975 | Umbro | — | — |

| 1975–1980 | Admiral | ||

| 1980–1982 | Adidas | ||

| 1982–1992 | Sharp Electronics | ||

| 1992–2000 | Umbro | ||

| 2000–2002 | Vodafone | ||

| 2002–2006 | Nike | ||

| 2006–2010 | AIG | ||

| 2010–2014 | Aon | ||

| 2014–2015 | Chevrolet | ||

| 2015–2018 | Adidas | ||

| 2018– | Kohler |

In an initial five-year deal worth £500,000, Sharp Electronics became the club's first shirt sponsor at the beginning of the 1982–83 season, a relationship that lasted until the end of the 1999–2000 season, when Vodafone agreed a four-year, £30 million deal.[142] Vodafone agreed to pay £36 million to extend the deal by four years, but after two seasons triggered a break clause in order to concentrate on its sponsorship of the Champions League.[142]

To commence at the start of the 2006–07 season, American insurance corporation AIG agreed a four-year £56.5 million deal which in September 2006 became the most valuable in the world.[143][144] At the beginning of the 2010–11 season, American reinsurance company Aon became the club's principal sponsor in a four-year deal reputed to be worth approximately £80 million, making it the most lucrative shirt sponsorship deal in football history.[145] Manchester United announced their first training kit sponsor in August 2011, agreeing a four-year deal with DHL reported to be worth £40 million; it is believed to be the first instance of training kit sponsorship in English football.[146][147] The DHL contract lasted for over a year before the club bought back the contract in October 2012, although they remained the club's official logistics partner.[148] The contract for the training kit sponsorship was then sold to Aon in April 2013 for a deal worth £180 million over eight years, which also included purchasing the naming rights for the Trafford Training Centre.[149]

The club's first kit manufacturer was Umbro, until a five-year deal was agreed with Admiral Sportswear in 1975.[150] Adidas received the contract in 1980,[151] before Umbro started a second spell in 1992.[152] Umbro's sponsorship lasted for ten years, followed by Nike's record-breaking £302.9 million deal that lasted until 2015; 3.8 million replica shirts were sold in the first 22 months with the company.[153][154] In addition to Nike and Chevrolet, the club also has several lower-level "platinum" sponsors, including Aon and Budweiser.[155]

On 30 July 2012, United signed a seven-year deal with American automotive corporation General Motors, which replaced Aon as the shirt sponsor from the 2014–15 season. The new $80m-a-year shirt deal is worth $559m over seven years and features the logo of General Motors brand Chevrolet.[156][157] Nike announced that they would not renew their kit supply deal with Manchester United after the 2014–15 season, citing rising costs.[158][159] Since the start of the 2015–16 season, Adidas has manufactured Manchester United's kit as part of a world-record 10-year deal worth a minimum of £750 million.[160][161] Plumbing products manufacturer Kohler became the club's first sleeve sponsor ahead of the 2018–19 season.[162]

Ownership and finances

Originally funded by the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company, the club became a limited company in 1892 and sold shares to local supporters for £1 via an application form.[20] In 1902, majority ownership passed to the four local businessmen who invested £500 to save the club from bankruptcy, including future club president John Henry Davies.[20] After his death in 1927, the club faced bankruptcy yet again, but was saved in December 1931 by James W. Gibson, who assumed control of the club after an investment of £2,000.[24] Gibson promoted his son, Alan, to the board in 1948,[163] but died three years later; the Gibson family retained ownership of the club through James' wife, Lillian,[164] but the position of chairman passed to former player Harold Hardman.[165]

Promoted to the board a few days after the Munich air disaster, Louis Edwards, a friend of Matt Busby, began acquiring shares in the club; for an investment of approximately £40,000, he accumulated a 54 per cent shareholding and took control in January 1964.[166] When Lillian Gibson died in January 1971, her shares passed to Alan Gibson who sold a percentage of his shares to Louis Edwards' son, Martin, in 1978; Martin Edwards went on to become chairman upon his father's death in 1980.[167] Media tycoon Robert Maxwell attempted to buy the club in 1984, but did not meet Edwards' asking price.[167] In 1989, chairman Martin Edwards attempted to sell the club to Michael Knighton for £20 million, but the sale fell through and Knighton joined the board of directors instead.[167]

Manchester United was floated on the stock market in June 1991 (raising £6.7 million),[168] and received yet another takeover bid in 1998, this time from Rupert Murdoch's British Sky Broadcasting Corporation. This resulted in the formation of Shareholders United Against Murdoch – now the Manchester United Supporters' Trust – who encouraged supporters to buy shares in the club in an attempt to block any hostile takeover. The Manchester United board accepted a £623 million offer,[169] but the takeover was blocked by the Monopolies and Mergers Commission at the final hurdle in April 1999.[170] A few years later, a power struggle emerged between the club's manager, Alex Ferguson, and his horse-racing partners, John Magnier and J. P. McManus, who had gradually become the majority shareholders. In a dispute that stemmed from contested ownership of the horse Rock of Gibraltar, Magnier and McManus attempted to have Ferguson removed from his position as manager, and the board responded by approaching investors to attempt to reduce the Irishmen's majority.[171]

In May 2005, Malcolm Glazer purchased the 28.7 per cent stake held by McManus and Magnier, thus acquiring a controlling interest through his investment vehicle Red Football Ltd in a highly leveraged takeover valuing the club at approximately £800 million (then approx. $1.5 billion).[172] Once the purchase was complete, the club was taken off the stock exchange.[173] In July 2006, the club announced a £660 million debt refinancing package, resulting in a 30 per cent reduction in annual interest payments to £62 million a year.[174][175] In January 2010, with debts of £716.5 million ($1.17 billion),[176] Manchester United further refinanced through a bond issue worth £504 million, enabling them to pay off most of the £509 million owed to international banks.[177] The annual interest payable on the bonds – which were to mature on 1 February 2017 – is approximately £45 million per annum.[178] Despite restructuring, the club's debt prompted protests from fans on 23 January 2010, at Old Trafford and the club's Trafford Training Centre.[179][180] Supporter groups encouraged match-going fans to wear green and gold, the colours of Newton Heath. On 30 January, reports emerged that the Manchester United Supporters' Trust had held meetings with a group of wealthy fans, dubbed the "Red Knights", with plans to buying out the Glazers' controlling interest.[181]

In August 2011, the Glazers were believed to have approached Credit Suisse in preparation for a $1 billion (approx. £600 million) initial public offering (IPO) on the Singapore stock exchange that would value the club at more than £2 billion.[182] However, in July 2012, the club announced plans to list its IPO on the New York Stock Exchange instead.[183] Shares were originally set to go on sale for between $16 and $20 each, but the price was cut to $14 by the launch of the IPO on 10 August, following negative comments from Wall Street analysts and Facebook's disappointing stock market debut in May. Even after the cut, Manchester United was valued at $2.3 billion, making it the most valuable football club in the world.[184]

Players

First-team squad

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Out on loan

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

Reserves and academy

- As of 28 February 2020[189]

List of under-23s and academy players with senior squad numbers

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Sir Matt Busby Player of the Year

Coaching staff

| Position | Staff |

|---|---|

| Manager | |

| Assistant manager | |

| First-team coaches | |

| Senior goalkeeping coach | |

| Assistant goalkeeping coach | |

| Head of athletic performance | |

| Fitness coaches | |

| First-team strength and power coach | |

| First-team lead sports scientist | |

| Head of first-team development | |

| Head of academy | |

| Under-23s manager | |

| Under-18s manager |

Managerial history

| Dates[201] | Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1878–1892 | Unknown | |

| 1892–1900 | ||

| 1900–1903 | ||

| 1903–1912 | ||

| 1912–1914 | ||

| 1914–1921 | ||

| 1921–1926 | ||

| 1926–1927 | Player-manager | |

| 1927–1931 | ||

| 1931–1932 | ||

| 1932–1937 | ||

| 1937–1945 | ||

| 1945–1969 | ||

| 1958 | Caretaker manager | |

| 1969–1970 | ||

| 1970–1971 | ||

| 1971–1972 | ||

| 1972–1977 | ||

| 1977–1981 | ||

| 1981–1986 | ||

| 1986–2013 | ||

| 2013–2014 | ||

| 2014 | Interim player-manager | |

| 2014–2016 | ||

| 2016–2018 | ||

| 2018– | Caretaker until 28 March 2019 |

Management

- Owner: Glazer family via Red Football Shareholder Limited[202]

Manchester United Limited

| Position | Name[203] |

|---|---|

| Co-chairmen | Avram Glazer Joel Glazer |

| Executive vice-chairman | Ed Woodward |

| Group managing director | Richard Arnold |

| Chief financial officer | Cliff Baty[204] |

| Chief operating officer | Collette Roche[205] |

| Non-executive directors | Bryan Glazer Kevin Glazer Edward Glazer Darcie Glazer Kassewitz Robert Leitão John Hooks Manu Sawhney |

Manchester United Football Club

| Office | Name |

|---|---|

| Honorary president | Martin Edwards[206] |

| Directors | David Gill Michael Edelson Sir Bobby Charlton Sir Alex Ferguson[207] |

| Club secretary | Rebecca Britain[208] |

| Director of football operations | Alan Dawson MBE |

Honours

Manchester United are one of the most successful clubs in Europe in terms of trophies won.[209] The club's first trophy was the Manchester Cup, which they won as Newton Heath LYR in 1886.[210] In 1908, the club won their first league title, and won the FA Cup for the first time the following year. Since then, they have gone on to win a record 20 top-division titles – including a record 13 Premier League titles – and their total of 12 FA Cups is second only to Arsenal (14). Those titles have meant they have also appeared a record 30 times in the FA Community Shield (formerly the FA Charity Shield), which is played at the start of each season between the winners of the league and FA Cup from the previous season; of those 30 appearances, Manchester United have won 21, including four times when the match was drawn and the trophy shared by the two clubs.

The club had a successful period under the management of Matt Busby, starting with the FA Cup in 1948 and culminating with becoming the first English club to win the European Cup in 1968, winning five league titles in the intervening years; however, the club's most successful decade came in the 1990s under Alex Ferguson; five league titles, four FA Cups, one League Cup, five Charity Shields (one shared), one UEFA Champions League, one UEFA Cup Winners' Cup, one UEFA Super Cup and one Intercontinental Cup. They also won the Double (winning the Premier League and FA Cup in the same season) three times during the 1990s; before their first in 1993–94, it had only been done five times in English football, so when they won a second in 1995–96 – the first club to do it twice – it was referred to as the "Double Double".[211] When they won the European Cup (now the UEFA Champions League) for a second time in 1999, along with the Premier League and the FA Cup, they became the first English club to win the Treble. That Champions League title gave them entry to the now-defunct Intercontinental Cup, which they also won, making them the only British team to do so. Another Champions League title in 2008 meant they qualified for the 2008 FIFA Club World Cup, which they also won; until 2019, they were the only British team to win that competition.

The club's most recent trophy was the UEFA Europa League, which they won in 2016–17. In winning that title, United became the fifth club to have won the "European Treble" of European Cup/UEFA Champions League, Cup Winners' Cup, and UEFA Cup/Europa League after Juventus, Ajax, Bayern Munich and Chelsea.[212][213]

Domestic

League

European

- European Cup/UEFA Champions League

- European Cup Winners' Cup

- Winners (1): 1990–91

- UEFA Europa League

- Winners (1): 2016–17

- European Super Cup

- Winners (1): 1991

Worldwide

- Intercontinental Cup

- Winners (1): 1999

- FIFA Club World Cup

- Winners (1): 2008

Doubles and Trebles

- Doubles

- League and FA Cup (3): 1993–94, 1995–96, 1998–99

- League and EFL Cup (1): 2008–09

- League and UEFA Champions League (2): 1998–99, 2007–08

- EFL Cup and UEFA Europa League (1): 2016–17

- Trebles

- League, FA Cup and UEFA Champions League (1): 1998–99

Especially short competitions such as the Charity/Community Shield, Intercontinental Cup (now defunct), FIFA Club World Cup or UEFA Super Cup are not generally considered to contribute towards a Double or Treble.[214]

Manchester United Women

A team called Manchester United Supporters Club Ladies began operations in the late 1970s and was unofficially recognised as the club's senior women's team. They became founding members of the North West Women's Regional Football League in 1989.[215] The team made an official partnership with Manchester United in 2001, becoming the club's official women's team; however, in 2005, following Malcolm Glazer's takeover, the club was disbanded as it was seen to be "unprofitable".[216] In 2018, Manchester United formed a new women's football team, which entered the second division of women's football in England for their debut season.[217][218][219][220][221]

Footnotes

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Sources are divided on the exact date of the meeting and subsequent name change. Whilst official club sources claim that it occurred on 26 April, the meeting was reported by the Manchester Evening Chronicle in its edition of 25 April, suggesting it was indeed on 24 April.

- Upon its formation in 1992, the Premier League became the top tier of English football; the Football League First and Second Divisions then became the second and third tiers, respectively. From 2004, the First Division became the Championship and the Second Division became League One.

References

- "Premier League Handbook Season 2015/16" (PDF). Premier League. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- "Man United must aim for top four, not title challenge – Mourinho". Reuters. 2 November 2018.

- "Marcus Rashford's 92nd minute winner enough for Man United to scrape a win at Bournemouth".

- "Premier League Handbook 2018–19" (PDF). Premier League. 30 July 2018. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Smith, Adam (30 November 2016). "Leeds United England's 12th biggest club, according to Sky Sports study". Sky Sports.

- McNulty, Phil (21 September 2012). "Liverpool v Manchester United: The bitter rivalry". BBC Sports.

- "BBC ON THIS DAY – 14 – 1969: Matt Busby retires from Man United". BBC News.

- "The 49 trophies of Sir Alex Ferguson – the most successful managerial career Britain has ever known". The Independent. London: Independent Print. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- Stewart, Rob (1 October 2009). "Sir Alex Ferguson successful because he was given time, says Steve Bruce". The Daily Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- Northcroft, Jonathan (5 November 2006). "20 glorious years, 20 key decisions". The Sunday Times. London: Times Newspapers. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Wilson, Bill (23 January 2018). "Manchester United remain football's top revenue-generator". BBC News (British Broadcasting Corporation). Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- "The Business Of Soccer". Forbes. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- "Manchester United is 'most valuable football brand'". BBC News (British Broadcasting Corporation). 8 June 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- Schwartz, Peter J. (18 April 2012). "Manchester United Again The World's Most Valuable Soccer Team". Forbes Magazine. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- Hamil (2008), p. 126.

- "Barça, the most loved club in the world". Marca. Retrieved 15 December 2014

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 8.

- James (2008), p. 66.

- Tyrrell & Meek (1996), p. 99.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 9.

- James (2008), p. 92.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 118.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 11.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 12.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 13.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 10.

- Murphy (2006), p. 71.

- Glanville, Brian (27 April 2005). "The great Chelsea surrender". The Times. London: Times Newspapers. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Barnes et al. (2001), pp. 14–15.

- "1958: United players killed in air disaster". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 6 February 1958. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Barnes et al. (2001), pp. 16–17.

- White, Jim (2008), p. 136.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 17.

- Barnes et al. (2001), pp. 18–19.

- Moore, Rob; Stokkermans, Karel (11 December 2009). "European Footballer of the Year ("Ballon d'Or")". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 19.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 110.

- Murphy (2006), p. 134.

- "1977: Manchester United sack manager". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 4 July 1977. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 20.

- Barnes et al. (2001), pp. 20–21.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 21.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 148.

- Barnes et al. (2001), pp. 148–149.

- "Arise Sir Alex?". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 27 May 1999. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- Bevan, Chris (4 November 2006). "How Robins saved Ferguson's job". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- Bloomfield, Craig (4 May 2017). "Clubs ranked by the number of times they have claimed trophy doubles".

- "Golden years: The tale of Manchester United's 20 titles". BBC Sport. 22 April 2013 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- "United crowned kings of Europe". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 26 May 1999. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- Hoult, Nick (28 August 2007). "Ole Gunnar Solskjaer leaves golden memories". The Daily Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 23 July 2011.

- Magnani, Loris; Stokkermans, Karel (30 April 2005). "Intercontinental Club Cup". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Hughes, Rob (8 March 2004). "Ferguson and Magnier: a truce in the internal warfare at United". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- "Ryan Giggs wins 2009 BBC Sports Personality award". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 13 December 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- "Viduka hands title to Man Utd". BBC Sport (British Broadcasting Corporation). 4 May 2003. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- "Man Utd win FA Cup". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 22 May 2004. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- "Manchester United's Champions League exits, 1993–2011". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. 8 December 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- Shuttleworth, Peter (21 May 2008). "Spot-on Giggs overtakes Charlton". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- McNulty, Phil (1 March 2009). "Man Utd 0–0 Tottenham (aet)". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- McNulty, Phil (16 May 2009). "Man Utd 0–0 Arsenal". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 16 May 2009.

- Ogden, Mark (12 June 2009). "Cristiano Ronaldo transfer: World-record deal shows football is booming, says Sepp Blatter". The Daily Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 9 January 2011.

- "Rooney the hero as United overcome Villa". ESPNsoccernet. 28 February 2010. Archived from the original on 3 March 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- Stone, Simon (14 May 2011). "Manchester United clinch record 19th English title". The Independent. London: Independent Print. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- "How Manchester United won the 2012–13 Barclays Premier League". premierleague.com. Premier League. 22 April 2013. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- "Sir Alex Ferguson to retire as Manchester United manager". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- "Sir Alex Ferguson to retire this summer, Manchester United confirm". Sky Sports. BSkyB. 8 May 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- "David Moyes: Manchester United appoint Everton boss". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 9 May 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- "Manchester United confirm appointment of David Moyes on a six-year contract". Sky Sports. BSkyB. 9 May 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- Jackson, Jamie (9 May 2013). "David Moyes quits as Everton manager to take over at Manchester United". guardian.co.uk. Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- "David Moyes sacked by Manchester United after just 10 months in charge". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. 22 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- Hassan, Nabil (11 May 2014). "Southampton 1–1 Man Utd". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- "Manchester United: Louis van Gaal confirmed as new manager". BBC Sport (British Broadcasting Corporation). 19 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- Jackson, Jamie (28 May 2014). "Manchester United owner Malcolm Glazer dies aged 86". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- Wilkinson, Jack (9 December 2015). "Wolfsburg 3–2 Man Utd: Champions League exit for van Gaal's men". Sky Sports (BSkyB). Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- Smith, Alan (21 May 2016). "Crystal Palace 1–2 Manchester United (aet): FA Cup final – as it happened!". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- Stone, Simon; Roan, Dan (23 May 2016). "Manchester United: Louis van Gaal sacked as manager". BBC Sport. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- "Jose Mourinho: Man Utd confirm former Chelsea boss as new manager". BBC Sport. 27 May 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Veevers, Nicholas (7 August 2016). "United lift Shield after late Zlatan Ibrahimovic winner". TheFA.com. The Football Association. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- "Ole Gunnar Solskjaer: Man Utd caretaker boss will 'get players enjoying football' again". BBC Sport. 20 December 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- "Ole Gunnar Solskjaer appointed Manchester United permanent manager". Sky Sports. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 49.

- Angus, J. Keith (1879). The Sportsman's Year-Book for 1880. Cassell, Petter, Galpin & Co. p. 182.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 48.

- "Adidas launches new United home kit for 2018/19". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 17 July 2018. Retrieved 17 July 2018.

- Ogden, Mark (26 August 2011). "Sir Alex Ferguson's ability to play the generation game is vital to Manchester United's phenomenal success". The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- "Revealed: New Man Utd home kit for 2019/20". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 16 May 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- Devlin (2005), p. 157.

- "Reds unveil new away kit". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 15 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- Sharpe, Lee (15 April 2006). "13.04.96 Manchester United's grey day at The Dell". The Guardian. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- Devlin (2005), p. 158.

- "United reveal blue third kit for 2014/15 season". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 29 July 2014. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- Devlin (2005), pp. 154–159.

- "New blue kit for 08/09". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 28 August 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- White, Jim (2008) p. 21.

- James (2008), p. 392.

- Shury & Landamore (2005), p. 54.

- Shury & Landamore (2005), p. 51.

- Shury & Landamore (2005), pp. 21–22.

- Shury & Landamore (2005), p. 24.

- Shury & Landamore (2005), pp. 33–34.

- Inglis (1996), p. 234.

- Rollin and Rollin, pp. 254–255.

- White, John (2007), p. 11.

- Barnes et al. (2001), pp. 44–45.

- "Man Utd 3–0 Birmingham". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 26 March 2006. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- Coppack, Nick (31 March 2007). "Report: United 4 Blackburn 1". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- Morgan (2010), pp. 44–48.

- Bartram, Steve (19 November 2009). "OT100 #9: Record gate". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- "Barclays Premier League Stats: Team Attendance – 2012–13". ESPN FC. ESPN Internet Ventures. 3 May 2013. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- "German Bundesliga Stats: Team Attendance – 2012–13". ESPN FC. ESPN Internet Ventures. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- "Spanish La Liga Stats: Team Attendance – 2012–13". ESPN FC. ESPN Internet Ventures. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- Rice, Simon (6 November 2009). "Manchester United top of the 25 best supported clubs in Europe". The Independent. London: Independent Print. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- "Local Supporters Clubs". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- "Top 100 Facebook fan pages". FanPageList.com. Retrieved 23 November 2015

- "Manchester United fans the Premier League's loudest, says study". ESPN FC. ESPN Internet Ventures. 24 November 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- "Fans' Forum". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- Barnes et al. (2001), p. 52.

- Smith, Martin (15 April 2008). "Bitter rivals do battle". The Daily Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Stone, Simon (16 September 2005). "Giggs: Liverpool our biggest test". Manchester Evening News. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- Rohrer, Finlo (21 August 2007). "Scouse v Manc". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- "Liverpool v Manchester United: The bitter rivalry". BBC Sport. 21 September 2012.

- "Which club has won the most trophies in Europe". 13 August 2015. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- "The 20 biggest rivalries in world football ranked – Liverpool vs Manchester Utd". The Telegraph. 20 March 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- Aldred, Tanya (22 January 2004). "Rivals uncovered". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- "Interview: Ryan Giggs". Football Focus. British Broadcasting Corporation. 22 March 2008. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- "Liverpool remain Manchester United's 'biggest rival' says Ryan Giggs". The Independent. 6 December 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- "The 7 Greatest Rivalries in Club Football: From Boca to the Bernabeu". The Bleacher Report. 26 November 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- Taylor, Daniel (9 January 2011). "The greatest challenge of Sir Alex Ferguson's career is almost over". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- Dunning (1999), p. 151.

- "Arsenal v Manchester United head-to-head record". Arsenal official web. Archived from the original on 1 November 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- Hayward, Paul (31 January 2010). "Rivalry between Arsène Wenger and Sir Alex Ferguson unmatched in sport". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- "Top 30 Football Club Brands" (PDF). Brand Finance. September 2011. Retrieved 4 October 2011.

- Badenhausen, Kurt (16 July 2012). "Manchester United Tops The World's 50 Most Valuable Sports Teams". Forbes. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- "Real Madrid becomes the first sports team in the world to generate €400m in revenues as it tops Deloitte Football Money League". Deloitte. 2 March 2010. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- Ozanian, Mike (27 January 2013). "Manchester United Becomes First Team Valued At $3 Billion". Forbes. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- Ozanian, Mike (6 June 2017). "The World's Most Valuable Soccer Teams 2017". Forbes. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- Hamil (2008), p. 116.

- Hamil (2008), p. 124.

- Hamil (2008), p. 121.

- "Beckham fever grips Japan". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 18 June 2003. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- Hamil (2008), p. 120.

- Hamil (2008), p. 122.

- Ducker, James (4 June 2009). "Manchester United show financial muscle after signing record £80m shirt contract". The Times. London: Times Newspapers. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- "Oilinvest to renegotiate Juventus sponsorship". SportBusiness (SBG Companies). 7 September 2006. Retrieved 28 May 2007.

- "Man Utd sign £56m AIG shirt deal". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 6 April 2006. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Smith, Ben; Ducker, James (3 June 2009). "Manchester United announce £80 million sponsorship deal with Aon". The Times. London: Times Newspapers. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- "DHL delivers new shirt deal". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 22 August 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- "Manchester United unveils two new commercial deals". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 22 August 2011. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- "Manchester United buy back training kit sponsorship rights from DHL". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. 26 October 2012. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- Ogden, Mark (7 April 2013). "Manchester United to sign £180m Aon deal to change name of Carrington training base". The Telegraph. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- "Admiral: Heritage". Admiral Sportswear. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- Devlin (2005), p. 149.

- Devlin (2005), p. 148.

- Hamil (2008), p. 127.

- "Man Utd in £300m Nike deal". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 3 November 2000. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Wachman, Richard (24 April 2010). "Manchester United fans call on corporate sponsors to back fight against Glazers". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- Edgecliffe, Andrew (4 August 2012). "GM in record Man Utd sponsorship deal". FT.com. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- "Chevrolet signs seven-year deal". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 30 July 2012. Retrieved 30 July 2012.

- "Premier League: Sportswear giants Nike to end Manchester United sponsorship". Sky Sports. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- Bray, Chad (9 July 2014). "Nike and Manchester United Set to End Equipment Partnership". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- Jackson, Jamie (14 July 2014). "Manchester United sign record 10-year kit deal with Adidas worth £750m". theguardian.com. Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- De Menezes, Jack (14 July 2014). "Manchester United and adidas announce record £75m-per-year deal after Nike pull out". independent.co.uk. Independent Print. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- "Kohler Unveiled as Shirt Sleeve Sponsor". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 12 July 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- Crick & Smith (1990), p. 181.

- Crick & Smith (1990), p. 92.

- White, Jim (2008), p. 92.

- Dobson & Goddard (2004), p. 190.

- "1989: Man U sold in record takeover deal". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 18 August 1989. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- Dobson & Goddard (2004), p. 191.

- Bose (2007), p. 157.

- Bose (2007), p. 175.

- Bose (2007), pp. 234–235.

- "Glazer Man Utd stake exceeds 75%". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 16 May 2005. Retrieved 11 August 2007.

- "Glazer gets 98% of Man Utd shares". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 23 June 2005. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- "Glazers Tighten Grip on United With Debt Refinancing". The Political Economy of Football. 8 July 2006. Retrieved 11 August 2008.

- "Manchester United reveal refinancing plans". RTÉ (Raidió Teilifís Éireann). 18 July 2006. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- "Manchester United debt hits £716m". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 20 January 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- "Manchester United to raise £500m". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 11 January 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- Wilson, Bill (22 January 2010). "Manchester United raise £504m in bond issue". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- Hughes, Ian (23 January 2010). "Man Utd 4–0 Hull". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- "Prime Minister Gordon Brown warns football over debts". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 25 January 2010. Retrieved 26 January 2010.

- Hassan, Nabil; Roan, Dan (30 January 2010). "Wealthy Man Utd fans approach broker about takeover". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- Gibson, Owen (16 August 2011). "Manchester United eyes a partial flotation on Singapore stock exchange". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- 1Hrishikesh, Sharanya; Pandey, Ashutosh (3 July 2012). "Manchester United picks NYSE for U.S. public offering". Thomson Reuters. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- Rushe, Dominic (10 August 2012). "Manchester United IPO: share prices cut before US stock market flotation". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- "Man Utd First Team Squad & Player Profiles". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Man Utd announce squad numbers for 2019/20 Premier League season". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 9 August 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- Carney, Sam (17 January 2020). "Maguire to be new United captain". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Bostock, Adam (1 June 2020). "Confirmed: United extend Ighalo loan deal". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "Man. United | UEFA Europa League | UEFA.com". UEFA.com. Union of European Football Associations. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- "Solskjaer announced as full-time manager". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 28 March 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- "Phelan confirmed as United assistant manager". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 10 May 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- "Michael Carrick, Kieran McKenna and Mark Dempsey to remain on Man Utd coaching staff". Sky Sports. 14 May 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- Luckhurst, Samuel (10 November 2019). "Ole Gunnar Solskjaer hails impact of new Manchester United coach Martyn Pert". Manchestereveningnews.co.uk. Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- "Richard Hartis appointed senior goalkeeping coach". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 22 June 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- "Man Utd appoint Craig Mawson as new assistant goalkeeping coach". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 30 December 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2019.

- "How Manchester United are getting their players fitter for the new season". Manchestereveningnews.co.uk. Manchester Evening News. 22 July 2019. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- Marshall, Adam (6 July 2019). "Reds confirm additions to first-team staff". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "Club announces academy restructure". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 22 July 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Marshall, Adam (29 July 2019). "Introducing Man Utd U23s lead coach Neil Wood". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Retrieved 24 November 2019.

- "Neil Ryan takes charge of United's Under-18s". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 21 July 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- Barnes et al. (2001), pp. 54–57.

- Red Football Shareholder Limited: Group of companies' accounts made up to 30 June 2009. Downloaded from Companies House UK

- "Board of Directors". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- "Manchester United appoints Cliff Baty as Chief Financial Officer". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 26 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- "The appointment of Collette Roche at Manchester United is a step forward for football – a game blighted by sexism". inews.com. iNews. 19 April 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- Gardner, Neil (8 October 2009). "Martin Edwards voices concerns over Manchester United's future". The Times. London: Times Newspapers. Retrieved 11 June 2010.

- "Sir Alex Ferguson latest: Manager retires but will remain a director". 8 May 2013.

- "Manchester United appoint Rebecca Britain as club secretary". Manchester Evening News. 29 March 2018. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- Bloomfield, Craig (13 August 2015). "Which club has won the most trophies in Europe? The most successful clubs from the best leagues revealed". talkSPORT. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- Shury & Landamore (2005), p. 8.

- "On This Day: United's Historic 'Double Double'". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 11 May 2020. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- "Manchester United win the UEFA Europa League". ManUtd.com. Manchester United. 24 May 2017. Archived from the original on 1 June 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- "Europa League final: Manchester United on the brink of unique achievement no other English club could ever match". talkSPORT. 23 May 2017. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- Rice, Simon (20 May 2010). "Treble treble: The teams that won the treble". The Independent. London: Independent Print. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- Wigmore, Tim. "Why Do Manchester United Still Not Have a Women's Team?". Bleacher Report.

- Leighton, Tony (21 February 2005). "United abandon women's game to focus on youth". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Manchester United get Women's Championship licence; West Ham join top flight". BBC Sport. 28 May 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "Manchester United granted place in Women's Championship by FA". The Independent. 28 May 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "Manchester United Women to play in FA Women's Championship next season". ESPN. 28 May 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "Manchester United granted FA Women's Championship place with West Ham in Super League". Sky Sports. 28 May 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "West Ham the big winners, Sunderland key losers in women's football revamp". The Guardian. 28 May 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

Further reading

- Andrews, David L., ed. (2004). Manchester United: A Thematic Study. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-33333-7.

- Barnes, Justyn; Bostock, Adam; Butler, Cliff; Ferguson, Jim; Meek, David; Mitten, Andy; Pilger, Sam; Taylor, Frank OBE; Tyrrell, Tom (2001) [1998]. The Official Manchester United Illustrated Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). London: Manchester United Books. ISBN 978-0-233-99964-7.

- Bose, Mihir (2007). Manchester Disunited: Trouble and Takeover at the World's Richest Football Club. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-121-0.

- Crick, Michael; Smith, David (1990). Manchester United – The Betrayal of a Legend. London: Pan Books. ISBN 978-0-330-31440-4.

- Devlin, John (2005). True Colours: Football Kits from 1980 to the Present Day. London: A & C Black. ISBN 978-0-7136-7389-0.

- Dobson, Stephen; Goddard, John (2004). "Ownership and Finance of Professional Soccer in England and Europe". In Fort, Rodney; Fizel, John (eds.). International Sports Economics Comparisons. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-98032-0.

- Dunning, Eric (1999). Sport Matters: Sociological Studies of Sport, Violence and Civilisation. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-09378-1.

- Hamil, Sean (2008). "Case 9: Manchester United: the Commercial Development of a Global Football Brand". In Chadwick, Simon; Arth, Dave (eds.). International Cases in the Business of Sport. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-7506-8543-6.

- Inglis, Simon (1996) [1985]. Football Grounds of Britain (3rd ed.). London: CollinsWillow. ISBN 978-0-00-218426-7.

- James, Gary (2008). Manchester: A Football History. Halifax: James Ward. ISBN 978-0-9558127-0-5.

- Morgan, Steve (March 2010). McLeish, Ian (ed.). "Design for life". Inside United (212). ISSN 1749-6497.

- Murphy, Alex (2006). The Official Illustrated History of Manchester United. London: Orion Books. ISBN 978-0-7528-7603-0.

- Shury, Alan; Landamore, Brian (2005). The Definitive Newton Heath F.C. SoccerData. ISBN 978-1-899468-16-4.

- Tyrrell, Tom; Meek, David (1996) [1988]. The Hamlyn Illustrated History of Manchester United 1878–1996 (5th ed.). London: Hamlyn. ISBN 978-0-600-59074-3.

- White, Jim (2008). Manchester United: The Biography. London: Sphere. ISBN 978-1-84744-088-4.

- White, John (2007) [2005]. The United Miscellany (2nd ed.). London: Carlton Books. ISBN 978-1-84442-745-1.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Manchester United F.C. |

| Wikinews has news related to: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manchester United FC. |

- Official website (in Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Japanese, Korean, and Spanish)

- Official statistics website

- Official Manchester United Supporters' Trust

- Manchester United F.C. on BBC Sport: Club news – Recent results and fixtures

- Manchester United at Sky Sports

- Manchester United at Premier League