The Wash

The Wash is a rectangular bay and estuary at the north-west corner of East Anglia on the East coast of England, where Norfolk meets Lincolnshire, and both border the North Sea. One of the broadest estuaries in the United Kingdom, it is fed by the rivers Witham, Welland, Nene and Great Ouse. It is a 62,046-hectare (153,320-acre) biological Site of Special Scientific Interest.[1][3] It is also a Nature Conservation Review site, Grade I,[4] a National Nature Reserve,[5] a Ramsar site,[6] a Special Area of Conservation[7] and a Special Protection Area.[8] It is in the Norfolk Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty[9] and part of it is the Snettisham Royal Society for the Protection of Birds nature reserve.[10]

| Site of Special Scientific Interest | |

| |

| Area of Search | Lincolnshire Norfolk |

|---|---|

| Grid reference | TF 537 402[1] |

| Interest | Biological |

| Area | 62,045.6 hectares (153,318 acres)[1] |

| Notification | 1984[1] |

| Location map | Magic Map |

| Designations | |

|---|---|

| Official name | The Wash |

| Designated | 30 March 1988 |

| Reference no. | 395[2] |

Geography

The Wash makes a large indentation in the coastline of Eastern England that separates the curved coast of East Anglia from Lincolnshire. It is a large bay with three roughly straight sides meeting at right angles, each about 15 miles (25 km) in length. The eastern coast of the Wash is entirely within Norfolk, and extends from a point a little north of Hunstanton in the north to the mouth of the River Great Ouse at King's Lynn in the south. The opposing coast, which is roughly parallel to the east coast, runs from Gibraltar Point to the mouth of the River Welland, all within Lincolnshire. The southern coast runs roughly north-west to south-east, connecting these two river mouths and is punctuated by the mouth of a third river, the River Nene.

Inland from the Wash the land is flat, low-lying and often marshy: these are the Fens of Lincolnshire, Cambridgeshire and Norfolk. To the east is the North Sea.

Owing to deposits of sediment and land reclamation, the coastline of the Wash has altered markedly within historical times. Several towns once on the coast of the Wash (notably King's Lynn) are now some distance inland. Much of the Wash itself is very shallow, with several large sandbanks, such as Breast Sand, Bulldog Sand, Roger Sand and Old South Sand, which are exposed at low tide, especially along the south coast. For this reason, navigation in the Wash can be hazardous.[11]

Two commercial shipping lane channels lead inland from The Wash, the River Nene leading to Port Sutton Bridge in Lincolnshire and further inland to the Port of Wisbech in Cambridgeshire, and the River Great Ouse leading to King's Lynn Docks in Norfolk. Both shipping lanes have their own maritime pilot stations to guide and navigate incoming and outgoing cargo ships in The Wash.

A re-survey of the coastline of The Wash carried out by The Ordnance Survey in 2011 revealed that an estimated additional 3,000 acres (12 km2) on its coastline had been created by accretion since previous surveys between 1960 and 1980.

Water temperature

The Wash varies enormously in water temperature throughout the year. Winter temperatures are brought near freezing from the cold North Sea flows. Summer water temperatures can reach 20–23 °C (68–73 °F) after prolonged high ambient air temperature and sun. This effect, which typically happens in the shallow areas around beaches and often only in pockets of water, is exaggerated by the large sheltered tidal reach.

Wash River

At the end of the latest glaciation, and while the sea level remained lower than it is today, the rivers Witham, Welland, Glen, Nene and Great Ouse joined into a large river.

The deep valley of the Wash was formed, not by an interglacial river, but by ice of the Wolstonian and Devensian stages flowing southwards up the slope represented by the modern coast and forming tunnel valleys, of which the Silver Pit is one of many. This process gave the Silver Pit its depth and narrowness. When the tunnel valley was free of ice and seawater, it was occupied by the river. This kept it free of sediment, unlike most tunnel valleys. Since the sea flooded it, the valley seems to have been kept open by tidal action. During the Ipswichian Stage, the Wash River probably flowed by way of the site of the Silver Pit, but the tunnel valley would not have been formed at this stage, as its alignment seems inconsistent.

Wildlife

The Wash is made up of extensive salt marshes, major inter-tidal banks of sand and mud, shallow waters and deep channels. As understanding of the importance of the natural marshes has increased in the 21st century, the seawall at Freiston has been breached in three places to increase the salt-marsh area, to provide extra habitat for birds, particularly waders, and as a natural flood-prevention measure. The extensive creeks in the salt marsh and the vegetation that grows there help to dissipate wave energy, so enhancing the protection afforded to land behind the salt marsh. This is an example of the recent exploration of the possibilities of sustainable coastal management by adopting soft engineering techniques, rather than with dykes and drainage. The same scheme includes new brackish lagoon habitat.

On the eastern side of the Wash, low chalk cliffs, with a noted stratum of red chalk, are found at Hunstanton. The gravel pits (lagoons) found at Snettisham RSPB reserve are an important roost for waders at high tide. This Special Protection Area (SPA) borders onto the North Norfolk Coast Special Protection Area. To the north-west, the Wash extends to Gibraltar Point, another SPA.

The partly confined nature of the Wash habitats, combined with ample tidal flows, allows shellfish to breed, especially shrimp, cockles and mussels. Some water birds such as oystercatchers feed on shellfish. It is also a breeding area for common tern, and a feeding area for marsh harriers. Migrating birds such as geese, duck and wading birds come to the Wash in large numbers to spend the winter, with an average total of around 400,000 birds present at any one time.[12] It has been estimated that some two million birds a year use the Wash for feeding and roosting during their annual migrations.

The Wash is recognised as being internationally important for 17 species of bird. They include pink-footed goose, dark-bellied brent goose, shelduck, pintail, oystercatcher, ringed plover, grey plover, golden plover, lapwing, knot, sanderling, dunlin, black-tailed godwit, bar-tailed godwit, curlew, redshank and turnstone.[12]

History

In Roman Britain, embankments were built around the Wash's margins to protect agricultural land from flooding. However, they fell into disrepair after the Roman withdrawal in AD 407.

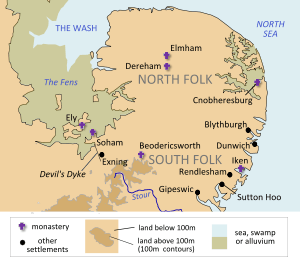

From 865 to sometime around 1066, the Wash was used by the Vikings as a major route to invade East Anglia and Middle England. Danes established themselves in Cambridge in 875. Before the 12th century, when drainage and embankment efforts led by monks began to separate the land from the estuarine mudflats, the Wash was a tidal part of The Fens that reached as far as Cambridge and Peterborough.

Local people put up fierce resistance against the Normans for some time after the 1066 Conquest.

The name Wash may have been derived from Old English wāse 'mud, slime, ooze'. The word Wasche is mentioned in the popular dictionary Promptorium parvulorum (about 1440) as a water or a ford (vadum). A chronicle tells us that King Edward VI passed the Wasshes as he visited the town of King's Lynn in 1548. By then, documents began to refer to the Waashe or Wysche, but only for the tidal sands and shoals of the rivers Welland and Nene. 16th-century scholars identified the Wash as the Æstuarium Metuonis ("The Reaping/Mowing/Cutting-Off Estuary") mentioned by Ptolemy in Roman times. They claimed this word was still in occasional use. William Camden characterized The Washes as "a very large arme" of the "German Ocean" (the North Sea), "at every tide and high sea covered all with water, but when the sea ebbeth, and the tide is past, a man may pass over it as on dry land, but yet not without danger", as King John learned not without his loss (see below). Inspired by Camden's account, William Shakespeare mentioned the Lincolne-Washes in his stage play King John (1616). During the 17th and 18th centuries the name Wash came to be used for the estuary itself.

Drainage and reclamation works around the Wash continued until the 1970s. Large areas of salt marsh were progressively enclosed by banks and converted to agricultural land. The Wash is now surrounded by artificial sea defences on all three landward sides. In the 1970s, two large circular banks were built in the Terrington Marsh area of the Wash, as part of an abortive attempt to turn the entire estuary into a fresh water reservoir. The plan failed, not least because the banks were built using mud dredged from the salt marsh, which salinated fresh water stored there.

Hanseatic League

From 13th century the market town and seaport of Bishop's Lynn became the first member trading depot (Kontor) in the Kingdom of England of the Hanseatic League of ports. During the 14th century, Lynn ranked as the most important port in England, when sea trade with Europe was dominated by the League. It still retains two medieval Hanseatic League warehouses: Hanse House built in 1475 and Marriott's Warehouse.

King John and his jewels

King John of England is said to have lost some of his jewels at the Wash in 1216.[13] According to contemporary reports, John travelled from Spalding, Lincolnshire, to Bishop's Lynn, Norfolk, but was taken ill and decided to return. While he took the longer route by way of Wisbech, he sent his baggage train along the causeway and ford across the mouth of the Wellstream, a route usable only at low tide. In his case the horse-drawn wagons moved too slowly for the incoming tide and many were lost.[14] However, scholars cannot agree on whether the king's jewels were inside the baggage train,[15] as there is evidence that his regalia were intact after the journey.[16]

The accident was said to have occurred somewhere near Sutton Bridge on the River Nene. The name of the river changed as a result of redirection of the Great Ouse in the 17th century. Bishop's Lynn was renamed as King's Lynn in the 16th century as a result of King Henry VIII's establishment of the Church of England.

John may have left his jewels in Lynn as security for a loan and arranged for their "loss". But that is considered an apocryphal account. He was recorded as staying the following night, 12–13 October 1216, at Swineshead Abbey, moving on to Newark-on-Trent, and dying of his illness on 19 October.[17]

Air weapons training range

A Ministry of Defence weapons Range Danger Area is located along a small region of The Wash coastline, reserved for Royal Air Force, Army Air Corps and NATO-allied bombing and air weapons training – RAF Holbeach, active since 1926, was historically originally part of the former RAF Sutton Bridge station. Another air-weapons training range located on The Wash – RAF Wainfleet, operating since 1938 – was decommissioned in 2010.

Local traditions

Sailing from out of the South Lincolnshire Fens into the Wash (especially for shell-fishing) is traditionally known locally as "going down below". The origin of the phrase is unknown.[18]

Landmarks

St Botolph's, the parish church of Boston (nicknamed the Boston Stump) is a Lincolnshire landmark. It can be seen on clear days from the Norfolk side of the Wash. The Outer Trial Bank, a remnant of a 1970s experiment, lies some 2 miles (3.2 km) off the Lincolnshire coast near the River Nene.

Proposed racetrack

In 1934 a proposal was made, supported by racing driver Malcolm Campbell, to build a 15-mile-long (24 km) race track on reclaimed land from Boston to Gibraltar Point, near Skegness. It would have been used as a road to Skegness when there was no racing. There was also to be a long lake for boat racing inside the track loop. The financial straits in the 1930s prevented the project from proceeding.

References

- "Designated Sites View: The Wash". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- "The Wash". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- "Map of The Wash". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- Ratcliffe, Derek, ed. (1977). A Nature Conservation Review. 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 11. ISBN 0521-21403-3.

- "Designated Sites View: The Wash". National Nature Reserves. Natural England. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Designated Sites View: The Wash". Ramsar Site. Natural England. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Designated Sites View: The Wash and North Norfolk Coast". Special Areas of Conservation. Natural England. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- "Designated Sites View: The Wash". Special Protection Areas. Natural England. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- "Norfolk Coast AONB Management Plan 2014-19: Other Conservation Designations within the AONB" (PDF). Norfolk Coast AONB. Retrieved 25 May 2018.

- "Snettisham". Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- See assembled navigational guidance.

- Waterbirds in the UK 2004/05: the wetland bird survey. Banks, Collier, Austin, Hearn and Musgrove. ISBN 1-904870-77-5

- A. L. Poole (1955). Domesday Book to Magna Carta, 1087-1216. Oxford History of England. p. 485. ISBN 0-19-821707-2.

- Neil Walker; Thomas Craddock (1849). The History of Wisbech and the Fens, by N. Walker and T. Craddock. R. Walker. pp. 211–212.

- John Steane (2003). The Archaeology of the Medieval English Monarchy. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-134-64159-8.

- Edward Francis Twining (1960). A History of the Crown Jewels of Europe. B. T. Batsford. p. 114.

- E. S. Kirkland (2008). A Short History of England for Young People. Lightning Source Incorporated. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-4437-7621-9.

- "When barges worked up the River Welland" (PDF). Lincolnshire Free Press. 9 February 1993. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

Further reading

- J. Cook and N. Ashton, "High Lodge, Mildenhall", Current Archaeology, No. 123 (1991)

- Waters, Richard (2014) [2003]. The Lost Treasure of King John: The Greatest Mystery of the Fens (3rd ed.). Lincoln: Tucann. ISBN 978-1-907516-33-7.

- R. G. West and J. J. Donner, "The Glaciation of East Anglia and the Midlands",Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London, vol. 112 (1955)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Wash. |