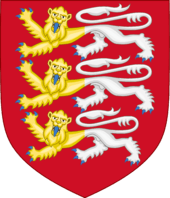

Royal Arms of England

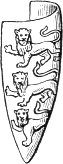

The Royal Arms of England are the arms first adopted in a fixed form[1] at the start of the age of heraldry (circa 1200) as personal arms by the Plantagenet kings who ruled England from 1154.[2] In the popular mind they have come to symbolise the nation of England, although according to heraldic usage nations do not bear arms, only persons and corporations do (however in Western Europe, especially in today's France, arms can be territorial civil emblems).[3] The blazon of the Arms of Plantagenet is: Gules, three lions passant guardant in pale or armed and langued azure,[4][5] signifying three identical gold lions (also known as leopards) with blue tongues and claws, walking past but facing the observer, arranged in a column on a red background. Although the tincture azure of tongue and claws is not cited in many blazons, they are historically a distinguishing feature of the Arms of England. This coat, designed in the High Middle Ages, has been variously combined with those of the Kings of France, Scotland, a symbol of Ireland, the House of Nassau and the Kingdom of Hanover, according to dynastic and other political changes occurring in England, but has not altered since it took a fixed form in the reign of Richard I (1189–1199), the second Plantagenet king.

| Royal Arms of England (Arms of Plantagenet) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Armiger | Monarchs of England |

| Adopted | Late 12th century |

| Blazon | Gules, three lions passant guardant in pale or armed and langued azure |

| Supporters | Various |

| Motto | Dieu et mon droit |

| Order(s) | Order of the Garter |

| Use |

|

Although in England the official blazon refers to "lions", French heralds historically used the term "leopard" to represent the lion passant guardant, and hence the arms of England, no doubt, are more correctly blazoned, "leopards". Without doubt the same animal was intended, but different names were given according to the position; in later times the name lion was given to both.[6]

Royal emblems depicting lions were first used by Danish Vikings,[7] Saxons (Lions were adopted in Germanic tradition around the 5th century,[8] they were re-interpreted in a Christian context in the western kingdoms of Gaul and Northern Italy in the 6th and 7th centuries) and Normans.[9][10][11] Later, with Plantagenets a formal and consistent English heraldry system emerged at the end of the 12th century. The earliest surviving representation of an escutcheon, or shield, displaying three lions is that on the Great Seal of King Richard I (1189–1199), which initially displayed one or two lions rampant, but in 1198 was permanently altered to depict three lions passant, perhaps representing Richard I's principal three positions as King of the English, Duke of the Normans, and Duke of the Aquitanians.[5][9][10][11] In 1340, Edward III laid claim to the throne of France, and thus adopted the Royal arms of France which he quartered with his paternal arms, the Royal Arms of England.[9] He placed the French arms in the 1st and 4th quarters. This quartering was adjusted, abandoned and restored intermittently throughout the Middle Ages as the relationship between England and France changed. When the French king altered his arms from semée of fleur-de-lys, to only three, the English quartering eventually followed suit. After the Union of the Crowns in 1603, when the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland entered a personal union, the arms of England and Scotland were marshalled (combined) in what has now become the Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom.[12] It appears in a similar capacity to represent England in the Arms of Canada and on the Queen's Personal Canadian Flag.[13] The coat of three lions continues to represent England on several coins of the pound sterling, forms the basis of several emblems of English national sports teams[14][15] (although with altered tinctures) and endures as one of the most recognisable national symbols of England.[3]

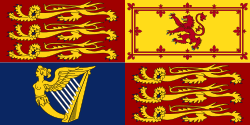

When the Royal Arms are in the format of an heraldic flag, it is variously known as the Royal Banner of England,[16] the Banner of the Royal Arms,[17] the Banner of the King (Queen) of England,[18][19] or by the misnomer the Royal Standard of England.[note 1] This Royal Banner differs from England's national flag, the St George's Cross, in that it does not represent any particular area or land, but rather symbolises the sovereignty vested in the rulers thereof.[4]

History

Origins

.jpg)

The first documented use of royal arms dates from the reign of Richard I (1189–1199). Much later antiquarians would retrospectively invented attributed arms for earlier kings, but their reigns pre-dated the systematisation of hereditary English heraldry that only occurred in the second half of the 12th century.[9] Lions may have been used as a badge by members of the Norman dynasty: a late-12th century chronicler reports that in 1128, Henry I of England knighted his son-in-law, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou, and gave him a gold lion badge. The memorial enamel created to decorate Geoffrey's tomb depicts a blue coat of arms bearing gold lions. His son, Henry II (1133–1189) used a lion as his emblem, and based on the arms used by his sons and other relatives, he may have used a coat of arms with a single lion or two lions, though no direct testimony of this has been found.[21] His children experimented with different combinations of lions on their arms. Richard I (1189–1199) used a single lion rampant, or perhaps two lions affrontés, on his first seal,[5] but later used three lions passant in his 1198 Great Seal of England, and thus established the lasting design of the Royal Arms of England.[5][21] In 1177, his brother John had used a seal depicting a shield with two lions passant guardant, but when he succeeded his brother on the English throne he would adopt arms with three lions passant or on a field gules, and these were then used, unchanged, as the royal arms ('King's Arms') by him and his successors until 1340.[5]

Development

In 1340, following the extinction of the House of Capet, Edward III claimed the French throne. In addition to initiating the Hundred Years' War, Edward III expressed his claim in heraldic form by quartering the royal arms of England with the Arms of France. This quartering continued until 1801, with intervals in 1360–1369 and 1420–1422.[5]

Following the death of Elizabeth I in 1603, the throne of England was inherited by the Scottish House of Stuart, resulting in the Union of the Crowns: the Kingdom of England and Kingdom of Scotland were united in a personal union under James VI and I.[22] As a consequence, the Royal Arms of England and Scotland were combined in the king's new personal arms. Nevertheless, although referencing the personal union with Scotland and Ireland, the Royal Arms of England remained distinct from the Royal Arms of Scotland, until the two realms were joined in a political union in 1707, leading to a unified Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom.[12]

| Kingdom of England (Under personal union with the Kingdom of Scotland from 1603–1707) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escutcheon | Period | Description | ||||

| 1189–1198 | The arms of Richard I are only known from two armorial seals, and hence the tinctures can not be determined. His First Great Seal showed one lion on half of the shield. It is debated whether this was meant to represent two lions combatant or a single lion, and if the latter, whether the direction in which the lion is facing is relevant or simply an artistic liberty. A simple lion rampant is most likely.[23] | ||||

| 1198–1340 1360–1369 | The arms on the second Great Seal of Richard I, used by his successors until 1340: Gules, three lions passant guardant in pale or (Three golden lions on a red field, representing the ruler of the Kingdom of England, Duchy of Normandy and the Duchy of Aquitaine).[5][9] | ||||

.svg.png) | 1340–1360 1369–1395 1399–1406 | Edward III adopted the Royal Arms of France Azure semé of fleurs de lys or (powdering of fleurs-de-lis on a blue field) – representing his claim to the French throne - and quartered the Royal Arms of England. | ||||

.svg.png) | 1395–1399 | Richard II adopted the attributed arms of King Edward the Confessor which he impaled with the Royal Arms of England, denoting a mystical union. | ||||

.svg.png) | 1406–1422 | Henry IV abandoned the attributed arms of King Edward the Confessor, and reduced the fleurs-de-lis to three, in imitation of Charles V of France.[9][24] | ||||

.svg.png) | 1422–1461 1470–1471 | Henry VI adopted the arms of France and impaled the arms of England, symbolising the dual monarchy, with France shown in the dexter position of greatest honour. | ||||

.svg.png) | 1461–1470 1471–1554 | Edward IV restored the arms of Henry IV.[24] | ||||

.svg.png) | 1554–1558 | Mary I and Philip impaled their arms. Philip's arms were: A. Arms quarterly Castile and Leon, B. per pale Aragon and Aragon-Sicily, the whole enté en point Granada; in base quarterly Austria, Burgundy ancient, Burgundy modern and Brabant, with an escutcheon (in the nombril point) per pale Flanders and Tyrol.[9][24] Although Queen Mary I's father, King Henry VIII, assumed the title of King of Ireland and this was further conferred upon King Philip, the arms were not altered to feature the Kingdom of Ireland.

| ||||

.svg.png) | 1558–1603 |

| ||||

.svg.png) | 1603–1649 1660–1689 |

| ||||

.svg.png) | 1689–1694 |

| ||||

.svg.png) | 1694–1702 |

| ||||

.svg.png) | 1702–1707 |

| ||||

Union with Scotland and Ireland

_RMG_L0161.tiff.jpg)

On 1 May 1707, the kingdoms of England and Scotland were merged to form that of Great Britain; this was reflected by impaling their arms in a single quarter. The claim to the French throne continued, albeit passively, until it was mooted by the French Revolution and the formation of the French First Republic in 1792.[5] During the peace negotiations at the Conference of Lille, from July to November 1797, the French delegates demanded that the King of Great Britain abandon the title of King of France as a condition of peace. The Acts of Union 1800 united the Kingdom of Great Britain with the Kingdom of Ireland to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Under King George III of the United Kingdom, a proclamation of 1 January 1801 set the royal style and titles and modified the Royal Arms, removing the French quarter and putting the arms of England, Scotland and Ireland on the same structural level, with the dynastic arms of Hanover moved to an inescutcheon.[5]

| Kingdom of Great Britain (and later, of Great Britain and Ireland) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Escutcheon | Period | Description |

.svg.png) | 1707–1714 | The impaled arms of England and Scotland reflecting their merging into one kingdom of "Great Britain". |

.svg.png) | 1714–1801 | The English and Scottish lions in the 4th quarter were replaced with a set of arms showing the origins of the House of Hanover as a result of the Act of Settlement. |

.svg.png) | 1801–1816 | The arms showing the status of the constituent realms of the United Kingdom: England, Scotland and Ireland. The Hanoverian dynastic arms have been moved to an inescutcheon with an electoral bonnet. |

.svg.png) | 1816–1837 | The arms showing Hanover raised to the status of a kingdom after the Napoleonic wars. |

| 1837–present | The Hanoverian dynastic arms have been dropped on the accession of Queen Victoria. As Hanover followed the salic law, she could not accede to the throne of Hanover. |

Contemporary

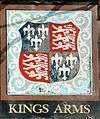

English heraldry flourished as a working art up to around the 17th century, when it assumed a mainly ceremonial role.[5] The Royal Arms of England continued to embody information relating to English history.[5] Although the Acts of Union 1707 placed England within the Kingdom of Great Britain, prompting new, British Royal Arms, the Royal Arms of England are still used occasionally in an official capacity,[27] and has continued to endure as one of the national symbols of England,[3] and has a variety of active uses. For instance, the coats of arms of both The Football Association[14][28] and the England and Wales Cricket Board[29] have a design featuring three lions passant, based on the historic Royal Arms of England. In 1997 (and again in 2002), the Royal Mint issued a British one pound (£1) coin featuring three lions passant to represent England.[30] To celebrate St George's Day, in 2001, Royal Mail issued first– and second-class postage stamps with the Royal Crest of England (a crowned lion), and the Royal Arms of England (three lions passant) respectively.[31]

The Royal Arms of England as depicted on the Kings Arms pub in Blakeney, Norfolk

The Royal Arms of England as depicted on the Kings Arms pub in Blakeney, Norfolk A British one pound (£1) coin, issued in 1997, featuring three lions passant, representing England.[30]

A British one pound (£1) coin, issued in 1997, featuring three lions passant, representing England.[30] A modern, commercially available Royal Banner of England, printed on polyester fabric

A modern, commercially available Royal Banner of England, printed on polyester fabric.jpg) The coat of arms of the Football Association (granted by the College of Arms in 1949), worn by the England national football team, are based on the Royal Arms of England.[14][15]

The coat of arms of the Football Association (granted by the College of Arms in 1949), worn by the England national football team, are based on the Royal Arms of England.[14][15] The coat of arms worn by England cricket team, the national football team removed the original crown to distinguish it from the cricket team in 1949.[32]

The coat of arms worn by England cricket team, the national football team removed the original crown to distinguish it from the cricket team in 1949.[32]

Crest, supporters and other parts of the achievement

Various accessories to the escutcheon (shield) were added and modified by successive English monarchs. These included a crest (with mantling, helm and crown); supporters (with a compartment); a motto; and the insignia of an order of knighthood. These various components made up the full achievement of arms.[24]

Royal crest

.svg.png)

The first addition to the shield was in the form of a crest borne above the shield. It was during the reign of Edward III that the crest began to be widely used in English heraldry. The first representation of a royal crest was in Edward's third Great Seal, which showed a helm above the arms, and thereon a gold lion passant guardant standing upon a chapeau, and bearing a royal crown on its head.[33] The design underwent minor variations until it took on its present form in the reign of Henry VIII: "The Royal Crown proper, thereon a lion statant guardant Or, royally crowned also proper".[33]

The exact form of crown used in the crest varied over time. Until the reign of Henry VI it was usually shown as an open circlet adorned with fleurs-de-lys or stylised leaves. On Henry's first seal for foreign affairs the design was altered with the circlet decorated by alternating crosses formy and fleurs-de-lys. From the reign of Edward IV the crown bore a single arch, altered to a double arch by Henry VII. The design varied in details until the late 17th century, but since that time has consisted of a jewelled circlet, above which are alternating crosses formy and fleurs-de-lys. From this spring two arches decorated with pearls, and at their intersection an orb surmounted by a cross formy.[33] A cap of crimson velvet is shown within the crown, with the cap's ermine lining appearing at the base of the crown in lieu of a torse.[33] The shape of the arches of the crown has been represented differently at different times, and can help to date a depiction of the crest.[33]

The helm on which the crest was borne was originally a simple steel design, sometimes with gold embellishments. In the reign of Elizabeth I a pattern of helm unique to the Royal Arms was introduced. This is a gold helm with a barred visor, facing the viewer.[34] The decorative mantling (a stylised cloth cloak that hangs from the helm) was originally of red cloth lined with ermine, but was altered to cloth of gold lined ermine by Elizabeth.[34]

Supporters

.jpg)

Animal supporters, standing on either side of the shield to hold and guard it, first appeared in English heraldry in the 15th century. Originally, they were not regarded as an integral part of arms, and were subject to frequent change. Various animals were sporadically shown supporting the Royal Arms of England, but it was only with the reign of Edward IV that their use became consistent. Supporters fell under the regulation of the Kings of Arms in the Tudor period. The heralds of that time also prochronistically created supporters for earlier monarchs, and although these attributed supporters were never used by the monarchs concerned, they were later used to signify them on public buildings or monuments completed after their deaths, for instance at St. George's Chapel, in Windsor Castle.[35][36]

The boar adopted by Richard III prompted William Collingbourne's quip "The Rat, the Cat, and Lovell the Dog, Rule all England under the Hog",[note 2][24] and William Shakespeare's derision in Richard III.[note 3][37] The red dragon, a symbol of the Tudor dynasty, was added upon the accession of Henry VII, and used by Henry VIII and Elizabeth I.[24] After the Union of the Crowns, the supporters of the arms of the British monarch became—and have remained—the Lion and the Unicorn, representing England and Scotland respectively.[24]

Garter and motto

Edward III founded the Order of the Garter in about 1348. Since then, the full achievement of the Royal Arms has included a representation of the Garter, encircling the shield. This is a blue circlet with gold buckle and edging, bearing the order's Old French motto Honi soit qui mal y pense ("Shame be to him who thinks evil of it") in gold capital letters.[34]

A motto, placed on a scroll below the Royal Arms of England, seems to have first been adopted by Henry IV in the early 15th century. His motto was Souverayne ("sovereign").[34] His son, Henry V adopted the motto Dieu et mon droit ("God and my right"). While this motto has been exclusively used since the accession of George I in 1714, and continues to form part of the Royal Arms of the United Kingdom, other mottoes were used by certain monarchs in the intervening period.[34] Veritas temporis filia ("truth is the daughter of time") was the motto of Mary I (1553–1558), Semper Eadem ("always the same") was used by Elizabeth I (1558–1603) and Anne (1702–1714), James I (1603–1625) sometimes used Beati pacifici ("blessed are the peacemakers"), while William III (1689–1702) used the motto of the House of Orange: Je maintiendrai ("I will maintain").[34]

Royal Banner of England

.jpg)

The Royal Banner of England is the English banner of arms and so has always borne the Royal Arms of England—the personal arms of England's reigning monarch. When displayed in war or battle, this banner signalled that the sovereign was present in person.[20] Because the Royal Banner depicted the Royal Arms of England, its design and composition changed throughout the Middle Ages.[20] It is variously known as the Royal Banner of England, the Banner of the Royal Arms,[17] the Banner of the King of England, or by the misnomer of the Royal Standard of England; Arthur Charles Fox-Davies explains that it is "a misnomer to term the banner of the Royal Arms the Royal Standard", because "the term standard properly refers to the long tapering flag used in battle, by which an overlord mustered his retainers in battle".[17] The archaeologist and antiquarian Charles Boutell also makes this distinction.[20] This Royal Banner differs from England's national flag, St George's Cross, in that it does not represent any particular area or land, but rather symbolises the sovereignty vested in the rulers thereof.[4]

In other banners

The Banner of the Duchy of Lancaster viz the Royal Banner of England defaced with a blue label of three points, each point containing three fleur-de-lis.

The Banner of the Duchy of Lancaster viz the Royal Banner of England defaced with a blue label of three points, each point containing three fleur-de-lis. The Royal Banner of the United Kingdom featuring the Royal Banner of England in the first and fourth quarters.

The Royal Banner of the United Kingdom featuring the Royal Banner of England in the first and fourth quarters..svg.png) The Royal Banner of the United Kingdom used in Scotland, featuring the Royal Banner of England in the second quarter.

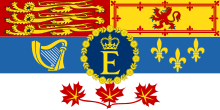

The Royal Banner of the United Kingdom used in Scotland, featuring the Royal Banner of England in the second quarter. The Royal Standard of Canada, featuring the Royal Banner of England in the First quarter of the first two divisions.

The Royal Standard of Canada, featuring the Royal Banner of England in the First quarter of the first two divisions.

Other roles and manifestations

Several ancient English towns displayed the Royal Arms of England upon their seals and, when it occurred to them to adopt insignia of their own, used the Royal Arms, albeit with modification, as their inspiration.[40] For instance, in the arms of New Romney, the field is changed from red to blue.[40] Hereford changes the lions from gold to silver, and in the 17th century was granted a blue border charged with silver saltires in allusion to its siege by a Scottish army during the English Civil War.[40] The town council of Faversham changes only the hindquarters of the three lions to silver.[39] Berkshire County Council bore arms with two golden lions in reference to its royal patronage and the Norman kings' influence upon the early history of Berkshire.[40]

The Royal Arms of England features on the tabard, the distinctive traditional garment of English officers of arms.[41] These garments were worn by heralds when performing their original duties—making royal or state proclamations and announcing tournaments. Since 1484 they have been part of the Royal Household.[42] Tabards featuring the Royal Arms continue to be worn at several traditional ceremonies, such as the annual procession and service of the Order of the Garter at Windsor Castle, the State Opening of Parliament at the Palace of Westminster, the coronation of the British monarch at Westminster Abbey, and state funerals in the United Kingdom.[41]

Thomas Hawley, an English officer of arms, wearing a tabard emblazoned with the Royal Arms of England

Thomas Hawley, an English officer of arms, wearing a tabard emblazoned with the Royal Arms of England The Arms of the Gibraltarian Government, which was granted by the College of Arms in 1836 to commemorate the Great Siege of Gibraltar, is a modification the Royal Arms of the United Kingdom.[43]

The Arms of the Gibraltarian Government, which was granted by the College of Arms in 1836 to commemorate the Great Siege of Gibraltar, is a modification the Royal Arms of the United Kingdom.[43] Edward, the Black Prince, wearing a surcoat emblazoned with the Royal Arms of England

Edward, the Black Prince, wearing a surcoat emblazoned with the Royal Arms of England The arms of Oriel College, Oxford alludes to the institution's regal foundation by using the Royal Arms of England with a silver border added for difference.[44]

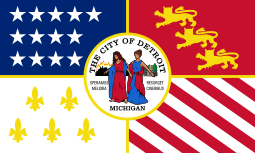

The arms of Oriel College, Oxford alludes to the institution's regal foundation by using the Royal Arms of England with a silver border added for difference.[44] The Flag of Detroit uses a stylized version of the Royal Arms to symbolize former British control of the city from 1760-1796

The Flag of Detroit uses a stylized version of the Royal Arms to symbolize former British control of the city from 1760-1796

See also

- Royal Badges of England

- Royal coat of arms of Scotland

- Royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom

- Royal coat of arms of France

- Coat of arms of Spain

- Royal of arms of León

- Royal arms of Castile

- Coat of arms of the Crown of Aragon

- Coat of arms of Norway

- List of coats of arms of the House of Plantagenet

Notes

- In A Complete Guide to Heraldry (1909), Arthur Charles Fox-Davies explains:

It is a misnomer to term the banner of the Royal Arms the Royal Standard. The term standard properly refers to the long tapering flag used in battle, by which an overlord mustered his retainers in battle.[17]

The archaeologist and antiquarian Charles Boutell also makes this distinction.[20] - This was a pun on Richard III (the Hog) and three of his staunchest supporters, Richard Ratcliffe (the Rat), William Catesby (the Cat) and Francis Lovell (the Dog).

- For instance, in Act 1, Scene III of Richard III, Margaret, Queen consort of England describes Richard as "Thou elvish-mark'd, abortive, rooting hog!"

References

Citations

- King Henry II (1154-1189) used proto-heraldic arms, showing one or two lions

- Jamieson 1998, pp. 14–15.

- Boutell 1859, p. 373: "The three golden lions upon a ground of red have certainly continued to be the royal and national arms of England."

- Fox-Davies 2008, p. 607.

- The First Foot Guards. "Coat of Arms of King George III". footguards.tripod.com. Retrieved 4 February 2010.

- Parker, James. "A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry". A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry. Retrieved 18 September 2015.

- "significant pre-figuration of medieval heraldry" John Onians, Atlas of World Art (2004), p. 58.

- Danuta Shanzer, Ralph W Mathisen, Romans, Barbarians, and the Transformation of the Roman World: Cultural Interaction and the Creation of Identity in Late Antiquity, (2013) p. 322.

- Brooke-Little 1950, pp. 205–222

- Brooke-Little 1981, pp. 3–6

- Paston-Bedingfield & Gwynn-Jones 1993, pp. 114–115.

- The Royal Household. "Union Jack". royal.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 30 June 2013. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- The Public Register of Arms, Flags and Badges of Canada. "The Flag of Her Majesty the Queen for personal use in Canada". gg.ca. Retrieved 28 August 2009.

- Briggs 1971, pp. 166–167.

- Ingle, Sean (18 July 2002). "Why do England have three lions on their shirts?". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- Thompson 2001, p. 91.

- Fox-Davies 1909, p. 474.

- Keightley 1834, p. 310.

- James 2009, p. 247.

- Boutell 1859, pp. 373–377.

- Ailes, Adrian (1982). The Origins of The Royal Arms of England. Reading: Graduate Center for Medieval Studies, University of Reading. pp. 52–63.

- Ross 2002, p. 56.

- Ailes. pp. 52–3, 64–74.

- Knight 1835, pp. 148–150.

- (in Spanish) Francisco Olmos, José María de. «Las primeras acuñaciones del príncipe Felipe de España (1554–1556): Soberano de Milán Nápoles e Inglaterra». «The First Coins of Prince Philip of Spain (1554–1556): Sovereign of Milan, Naples and England», pp. 165–166. Documenta & Instrumenta, 3 (2005). Madrid, Universidad Complutense. PP. 155–186.

- Arnaud Bunel's Héraldique européenne site

- "The Grand Procession", When the Queen was Crowned (1976), Brian Barker O.B.E.

- "England Football Online – The Three Lions". englandfootballonline.com. Archived from the original on 12 September 2010. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- England Wales Cricket Board

- Royal Mint (2010). "The United Kingdom £1 Coin". royalmint.com. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- "Three lions replace The Queen on stamps". telegraph.co.uk. 6 March 2001. Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- Why Do England’s Cricketers Wear the Iconic Crest on Their Chest? Archived 3 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 10 September 2012. The Cricket Blog.

- Brooke-Little 1981, pp. 4–8.

- Brooke-Little 1981, p. 16.

- Brooke-Little 1981, p. 9.

- Paston-Bedingfield & Gwynn-Jones 1993, p. 117.

- Hall 1853, p. 74.

- Woodward 1997, pp. 50–54.

- Faversham Town Council (2010). "Faversham Coat of Arms". The Faversham Website. faversham.org. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- Scott-Giles 1953, p. 11.

- College of Arms. "The history of the Royal heralds and the College of Arms". college-of-arms.gov.uk. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- Elston, Laura (8 September 2009). "Herald's tabard". The Independent. independent.co.uk. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- Sumner 2001, p. 9.

- "The name and arms of the College". oriel.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 24 June 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

Sources

- Boutell, Charles (1859). "The Art Journal London". 5. Virtue: 373–376. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Briggs, Geoffrey (1971). Civic and Corporate Heraldry: A Dictionary of Impersonal Arms of England, Wales and N. Ireland. London: Heraldry Today. ISBN 0-900455-21-7.

- Brooke-Little, J.P., FSA (1978) [1950]. Boutell's Heraldry (Revised ed.). London: Frederick Warne LTD. ISBN 0-7232-2096-4.

- Brooke-Little, J.P., FSA, MVO, MA, FSA, FHS (1981). Royal Heraldry. Beasts and Badges of Britain. Derby: Pilgrim Press Ltd. ISBN 0-900594-59-4.

- Fox-Davies, Arthur Charles (2008) [1909]. A Complete Guide to Heraldry. READ.

- Hall, Samuel Carter (1853). The Book of British Ballads. H. G. Bohn.

- Hassler, Charles (1980). The Royal Arms. ISBN 0-904041-20-4.

- James, George Payne Rainsford (2009). The History of Chivalr y. General Books LLC.

- Jamieson, Andrew Stewart (1998). Coats of Arms. Pitkin. ISBN 978-0-85372-870-2.

- Knight, Charles (18 April 1835). "English Regal Arms and Supporters". The Penny Magazine. 4. Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge.

- Keightley, Thomas (1834). The crusaders; or, Scenes, events, and characters, from the times of the crusades. 2 (3rd ed.). J. W. Parker.

- Paston-Bedingfield, Henry; Gwynn-Jones, Peter (1993). Heraldry. Greenwich Editions. ISBN 0-86288-279-6.

- Robson, Thomas (1830). The British Herald. Turner & Marwood.

- Ross, David (2002). Chronology of Scottish History. Geddes & Grosset. ISBN 1-85534-380-0.

- Scott-Giles, Wilfrid (1953). Civic Heraldry of England and Wales (2nd ed.). London: J M Dent & Sons.

- Sumner, Ian (2001). British Colours & Standards 1747–1881 (2): Infantry. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-201-6.

- Thomson, D. Croal (2001). Fifty Years of Art, 1849–1899: Being Articles and Illustrations Selected from 'The Art Journal'. Adegi Graphics LLC.

- Woodward, Jennifer (1997). The Theatre of Death: The Ritual Management of Royal Funerals in Renaissance England, 1570–1625. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-704-7.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |

.svg.png)

.svg.png)