Sheffield Rules

The Sheffield Rules was a code of football devised and played in the English city of Sheffield between 1858 and 1877. The rules were initially created and revised by Sheffield Football Club, with responsibility for the laws passing to the Sheffield Football Association upon that body's creation in 1867. The rules spread beyond the city boundaries to other clubs and associations in the north and midlands of England, making them one of the most popular forms of football during the 1860s and 1870s.

_1859.png)

In 1863, the newly-formed London-based Football Association (FA) published its own laws of football. Between 1863 and 1877, the FA and Sheffield laws co-existed, with each code at times influencing the other. Several games were played between Sheffield and London teams, using both sets of rules. After several disputes, the two codes were unified in 1877 when the Sheffield FA voted to adopt the FA laws, following the adoption of a compromise throw-in law by the FA.[1]

The Sheffield rules had a major influence on how the modern game of football developed. Among other things they introduced were the concepts of corners, and free kicks for fouls.[2] Games played under the rules are also credited with the development of heading, following the abolition of the fair catch, and the origins of the goalkeeper and forward positions.[3] In 1867, the world's first competitive football tournament was played under Sheffield Rules.

Background

The oldest recorded football match in Sheffield occurred in 1794 when a game of mob football was played between Sheffield and Norton (at the time a Derbyshire village) that took place at Bents Green. The game lasted three days, which was not unusual for matches at the time. It was noted that although there were some injuries no-one was killed during the match.[4] The Clarkehouse Road Fencing Club had been playing football since 1852.[5] The city was home to a number of sports clubs and the popularity of cricket had led to the chairman of Sheffield Cricket Club to suggest the construction of Bramall Lane.[6]

By the 1850s there were several versions of football played in public schools and clubs throughout England.[7] Their rules were generally inaccessible outside of the schools. There the football tended to be unorganised and fairly lawless games known as mob football. Although there are matches between small, equal numbered teams it remained a minority sport until the 1860s.[8]

During the winter months in 1855 the players of Sheffield Cricket Club organised informal football matches in order to retain fitness until the start of the new season.[6] Two of the players were Nathaniel Creswick (1826–1917) and William Prest (1832–1885), both of whom were born in Yorkshire. Creswick came from a Sheffield family of silver plate manufacturers that dated back several centuries. After being educated at the city's Collegiate School he became a solicitor. Prest's family had moved from York while he was a child. His father bought a wine merchants that William subsequently took over. Both men were keen sportsmen. Creswick enjoyed a number of sports including cricket and running. Prest played cricket for the All England XI and also captained Yorkshire on several occasions.[9] The inaugural meeting of Sheffield F.C. took place on 24 October 1857 at Parkfield House in the suburb of Highfield.[10] The original headquarters would become a greenhouse on East Bank Road. The adjacent field was used as their first playing ground.[11]

History of the laws

Laws of Sheffield Football Club (1858)

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

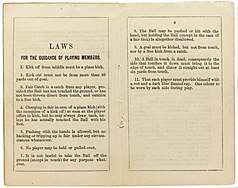

The first laws of Sheffield Football Club were approved at a general meeting at the Adelphi Hotel on 28 October 1858.[12] The club's minutes book is still available, and records changes made during the laws' development.[13] Notable features of the rules included:[14]

- Handling was forbidden, with the exception of "pushing" or "hitting" the ball with the hands, and a fair catch (defined as a catch from another player without the ball touching the ground).

- "Hacking" (kicking), tripping, and holding opponents were all forbidden, but pushing and charging were allowed.

- A free kick was awarded for a fair catch, but a goal could not be scored from such a free kick.

- A goal could be scored only by kicking (the 1858 laws do not specify the dimensions or type of the goal in further detail).

- The throw-in was awarded to the first team to touch the ball after it went out of play. The ball had to be thrown in at right-angles to the touchline.

- When the ball went out of play over the goal-line, there was a "kick-out" from 25 yards.

- There was no offside law.

- Like many rules of that era, the Sheffield rules did not dictate the numbers on each side.[15]

The origin of the 1858 Sheffield rules has been the subject of some academic debate. Adrian Harvey denies any public school influence, arguing that the rules were derived from "ideas generally current in the wider society".[16] In response, Tony Collins has demonstrated that there is a substantial similarity in wording between many of the Sheffield rules and the older Rugby School rules.[17][18] Local influences may also have played a role: many of the original members of Sheffield FC were from the local Collegiate School, which favoured the kicking style of the game, rather than handling the ball. The kicking game was also prevalent in the local villages of Penistone and Thurlstone.[19]

The club rules also dictated that any disputes on the field would be resolved by any committee members present — an early reference to the position now occupied by the referee.[20]

At the club's next annual general meeting in October 1859, a committee was appointed to revise the laws and prepare them for publication.[21] The laws were subsequently published later that year with only minor revisions.[22][23]

Amendment of 1860

On 31 January 1860, a meeting was held where it was resolved that Law 8 should be expunged and replaced with "Holding the ball (except in the case of a free kick) or knocking or pushing it on is altogether disallowed".[24] This left the fair catch as the only form of handling permitted by the laws.

Amendments of 1861

At the annual general meeting of Sheffield FC held in October 1861, the following amendments were made to the rules:[25]

- The kick-out [roughly equivalent to a goal-kick] had to be taken from within 10 yards of the goal (rather than the previous 25 yards). It was clarified that the kick-out should take place whenever the ball went behind the line of the goal-posts without going into goal.

- Two flags were placed in line with the goal-posts, each flag being four yards to the side of one of the posts.

- The throw-in had to touch the ground before coming into contact with a player. It was clarified that the throw-in had to be taken from the place where the ball went into touch.

Proposals to ban pushing and to introduce "rouges" were rejected.

Laws of Sheffield FC (1862)

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

On 31 January 1862, Sheffield FC held a meeting at which a new set of rules was considered. The rules were confirmed one week later, and published later the same year as Sheffield FC's second formal set of laws.[26] The major changes made in the 1862 rules were:[27][28]

- A change of ends at half-time was introduced, but only if no goal was scored in the first half.

- The dimensions of the goal were specified, with two "goal sticks" 12 feet (4 yards) apart, and a crossbar 9 feet from the ground.

- The "rouge" was introduced as a tiebreaker.

The rouge

A contemporary newspaper report of the 1862 Sheffield FC meeting reported that the 'most important alteration is the adoption of "rouges," which will have the effect of preventing matches to result in "draws."'[27]

The rouge originated in the Eton Field Game, where it was awarded when a player touched the ball down behind the opponents' goal-line in a somewhat similar manner to today's "try" in rugby.[29]

Sheffield FC encountered the rouge in a match of 17 December 1860, when the club played against the 58th Regiment, winning by one goal and 10 rouges to one goal and 5 rouges.[30] Reports of later Sheffield FC games during 1860 and 1861, however, do not mention rouges.[31] At the club's annual meeting in October 1861, as mentioned above, Sheffield FC specifically rejected a proposal to add rouges to its own code.[25]

Although the Sheffield laws defining the rouge bore a great deal of similarity to the equivalent rules of the Eton Field Game,[32] there were also significant differences. Sheffield made use of "rouge flags" on the goal-line at a distance of 4 yards (3.7 m) from each goal-post (as mentioned above, these flags had been added to the field of play in 1861). A rouge could be scored by touching the ball down only after it had been kicked between the two rouge flags, without going into the goal (Eton did not use rouge flags, permitting a rouge to be scored at any distance from the goal). Sheffield also removed Eton's requirement that the attacking player who kicked the ball behind the goal-line had to be "bullied" (tackled / mauled).

In the Sheffield 1862 rules, as at Eton, the rouge was immediately followed by a set-piece in front of goal ("one of the defending side must stand post two yards in front of the goal sticks"). In the Eton game, we know from detailed descriptions that this situation was somewhat similar to a rugby scrummage.[33]

The new laws were adopted almost immediately, with Sheffield recorded as beating Norton on 22 February 1862 by "one goal and one rouge to nothing".[34] A detailed description of a rouge being scored is found in a contemporary report from the Youdan Cup final of March 1867:[35]

After half an hour's play the ball was kicked by Elliott, not through the goal, but just over it, and was touched down by Ash in splendid style, after running round two of his opponents before getting to the ball, thus securing a rouge.

Developments between 1862 and 1867

The 1862 laws, like those of 1858, made no provision for offside. In a letter to The Field in February 1867, Sheffield FC secretary Harry Chambers wrote that Sheffield FC had adopted a rule at the beginning of the 1863 season requiring one opponent to be level or closer to the opponent's goal.[36] This claim is supported in a letter from secretary William Chesterman to the FA in 1863.[37]

At Sheffield FC's 1865 annual general meeting, it was resolved that "[t]hat for the future we play the [strict] offside rule, but if the other Sheff[iel]d Clubs do not adopt the same rule, we play our Matches with them according to our present rules". Another resolution stated that "a letter [should] be written to Notts Secretary saying that we will adopt the offside rule if they will give up making the mark in case of a free kick, & also the free kick at goal".[38][36]

This offside law was abandoned at the end of the 1865-66 season, with Sheffield FC reverting to the weaker one-player rule.[36][39] A newspaper article of January 1867 reported that '[t]he [stricter, FA-style] off-side rule has been played in Sheffield, but was universally disapproved of. It was found to be the cause of much discontent, and produced a most unsatisfactory state of things, it being so difficult, in the excitement of a close match, to distinguish what players were "off," and what "on" side. ... It was, therefore, abandoned, and now, as formerly, the only restriction upon the position of any player in the field is, that he must not be nearer to his adversaries' goal than the nearest of the defending side.'[40]

Surviving club records indicate that the rules could be varied for individual matches (e.g. 9 May 1863 v. Garrison "allowed striking & throwing the ball", 28 October 1865 v. Mackenzie "played the offside rules", 11 November 1865 vs. Norton "Played at East Bank to the old rules").[12]

Sources for the exact laws played during this period are scarce. As noted above, our best source for the offside law during these years is a letter written to The Field newspaper some years later. A letter sent from club secretary William Chesterman to the Football Association in February 1866 strongly supported an FA proposal to abolish the fair catch,[41] suggesting that there was already some appetite within the club for its removal from the Sheffield code (the fair catch had survived in the 1862 laws, but would later be abolished in the Sheffield Association laws of 1867, as described below). A copy of the newly-founded (Sheffield) Mechanics' FC rulebook for 1865-66 is largely identical to the Sheffield FC 1862 laws, but with two variations, which may or may not be related to developments at Sheffield FC:[42]

- a free kick is awarded for illegal handling (as in the draft Sheffield FC laws of 1858 and the future Sheffield Association laws of 1867)

- when the ball is kicked out "at the goal-sides", a throw-in is taken from the corner-flag (foreshadowing a similar Sheffield Association rule introduced in October 1867, as described below).

Laws of the Sheffield Football Association (1867)

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

In March 1867, the newly-formed Sheffield Football Association issued its first set of laws.[43] The text of the laws of the [London] Football Association, which had been amended the previous month, was used as a starting-point, with the Sheffield clubs making changes to reflect the distinctive features of their game.[44]

Significant new features of the 1867 laws (relative to the 1862 Sheffield FC laws) were:

- Handling was completely banned, and was punished with an indirect free-kick (from which neither a goal nor a rouge could be scored).

- The rouge no longer required a touch-down: it was scored whenever the ball was kicked between the rouge flags and under the bar. The rouge was followed by a "kick out" for the defending side, rather than the previous "stand post" procedure.

- Pushing was forbidden.

- The throw-in was awarded against the side kicking the ball out of play (rather than to the first team to touch the ball).

- The minimum distance of 6 yards for the throw-in was removed.

- The weak off-side law (requiring one opponent to be level or closer to the opponent's goal) was added.

- The "kick out" after the ball goes out of play behind the goal-line was from within 6 yards of the goal (rather than the previous 10 yards).

- Ends were changed after each goal.

October 1867 amendment

In October 1867, an amendment was made to the laws whereby there was a "kick-out" only after the ball was kicked directly over the crossbar. In all other cases where the ball went out of play over the goal-line, the game was restarted by a throw, from the point where the ball crossed the goal-line, ten yards towards the opposite goal, awarded against the team who put the ball out of play.[45]

Laws of the Sheffield Football Association (1868)

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

At its meeting in October 1868, the Sheffield Association made changes that altered many aspects of the game:[46][47]

- The rouge was abolished, with the rouge flags being removed.

- The width of the goal was doubled to eight yards (thus making the Sheffield goal the same width as the FA goal, though the height of the Sheffield goal remained greater, at nine feet rather than eight feet).

- The throw-in from touch was replaced with a kick-in, which could go in any direction.

- The corner-kick was introduced. It applied whenever the ball went out of play over the goal-line to the side of the goal, and was awarded against the team who kicked the ball out of play. (When the ball went out of play directly over the bar, regardless of which team kicked it out, it was still a kick to the defending team from within six yards of the goal).

- The free-kick, previously awarded only for handling, was extended to cases of tripping, hacking, and pushing.

- The fair catch, abolished in 1867, was reintroduced. It was rewarded with a free-kick. All handling, other than a fair catch, remained forbidden.

- For the first time, the law made reference to match officials. Each team was entitled to nominate an "umpire", who would officiate in the half of the field defended by his own team.

Laws of the Sheffield Football Association (1869)

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Further changes were made at the Sheffield Association's meeting of October 1869:[48][49][50][51]

- Handling the ball was allowed in the case of an attempted catch, in addition to a successful fair catch.

- Handling was permitted within three yards of a player's own goal.

- The distance opponents had to retreat at a free kick was increased from three yards to six yards.

- The fair catch, while still permitted, was no longer rewarded with a free kick.

Laws of the Sheffield Football Association (1871)

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

At an "adjourned general meeting", held in January 1871, the Association voted to prohibit catching or handling the ball (with the exception of defenders within three yards of their own goal).[52] The change was initially made on a temporary basis, until the end of the season, "with a view to its future abolishment". During an "animated discussion" on the question, defenders of the fair catch "objected to the continual chopping and changing ... 'catching' having been abandoned on a previous occasion [from 1867 to 1868]".[52]

At the annual general meeting, held in October of the same year, the Sheffield Association heard from a representative of the "South Derbyshire Football Association" whose members, having trialled both the FA and Sheffield rules, had "decided almost to a man in favour of Sheffield".[53] The Derbyshire group was "determin[ed] to join the Sheffield Association, should that body decide to abolish catching".[53] After this, a total ban on handling was proposed. Objectors countered that "the grounds in Sheffield and neighbourhood were unfit for the non-catching rule, on account of their hilly nature", but they were voted down, with the following changes being made:

- The fair catch was once again abolished.

- Handling was permitted only if the hand or arm was not "extended from the body".

- Charging from behind was banned, and punished with an indirect free-kick.

It was noted that these changes left Sheffield laws very close to those of the FA, with offside being the biggest remaining difference. The meeting continued by criticising the FA's "ridiculous" offside law (which required three opponents to be closer to the opposing goal), and its arrogance in refusing to play any rules but its own.[53]

Laws of the Sheffield Football Association (1875)

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The following changes were made at the Sheffield Association's meeting of February 1875:[54][55][56]

- The height of the crossbar was lowered from nine feet to eight feet, thus making the dimensions of the Sheffield goal identical to those of the FA goal.

- The FA law for changing ends was adopted: ends were always changed at half-time; they were no longer changed after each goal.

- The goalkeeper (not a designated individual as in the FA laws, but the nearest defender to the goal) was permitted to handle the ball.

- The umpires were supplied with flags.

Disputes between the Sheffield Association and the FA remained over the questions of throw-ins/kick-ins and offside. The FA had repeatedly rejected Sheffield's laxer offside rule at its own 1872, 1873 and 1874 meetings.[57][58][59][60][61] Furthermore, the FA had that very same month rejected a proposal by the Sheffield Association to introduce kick-ins instead of throw-ins.[62]

At the Sheffield Association's meeting, a proposal for Sheffield to adopt the FA's stricter offside law was rejected, with a contemporary report stating "[w]e do not doubt that if the Londoners [i.e. the FA] had shown a more conciliatory spirit [with respect to the throw-in rule], the off-side rule would have been accepted".[63]

Laws of the Sheffield Football Association (1876)

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Another proposal to introduce the FA's 3-player offside law was "negatived by a large majority", with opponents citing the rough nature of the grounds played on by the Sheffield teams, and claiming that "the strong defence it [the FA's offside rule] admits of would in many instances prevent any likelihood of a score being made".[64] The FA's rejection of Sheffield's kick-in law at its own annual meeting (held one week earlier) was said to have influenced the feeling of the Sheffield meeting.[64]

Only one change to the laws was made, with the FA's law on handling the ball being adopted.

Adoption of the FA laws (1877)

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The dispute between the Sheffield Association and the FA came to a head in 1877. At the regular meeting of the FA, in February, the Sheffield Association again proposed its kick-in rule, while Clydesdale FC proposed a compromise rule which retained the throw-in but allowed it to go in any direction. The Sheffield Association agreed to withdraw its own proposal in favour of Clydesdale FC's compromise. However, even this compromise proposal was rejected, "to the intense regret of those who desired one common code of rules".[65] This rejection prompted the publication of a pseudonymous letter in The Sportsman decrying the "hasty, ill-judged decision ... bringing the Football Association into disrepute", and denying that it represented "the general body of [Football] Association players -- even of those in London".[66] A subsequent extraordinary general meeting of the FA was held on the 17th of April, at which the Clydesdale amendment was reconsidered and passed.[67] As a result of this change in the FA laws, the Sheffield Association held a meeting one week later at which it agreed to abandon its own rules and accept the FA laws.[68]

The principal changes made by the Sheffield Association in going from its own laws of 1876 to the FA laws of 1877 were the following:

- Adoption of the stricter 3-player FA offside law

- Replacement of the kick-in from touch with the throw-in (which could still be thrown in any direction)

- A goal-kick (rather than a defensive corner-kick) was now awarded when an attacking player kicked the ball out of play over the goal-line, but not directly over the goal.

- An attacking corner-kick (rather than a goal-kick) was now awarded when a defender kicked the ball out of play directly over the goal

Later developments

Despite its adoption of the FA laws in 1877, the Sheffield Association continued to consider proposed alterations to the rules independently. At its February 1879 meeting:[69]

It was proposed by Mr. T. Banks, on behalf of the Norfolk Club, to add to law 8 — "If any player of the defending side, except the goalkeeper, stop the ball with his hands within three yards of the goal, when it is going in goal, it shall count a goal to the opponents."[70]

After a "long and noisy discussion", the change was rejected.

The continued importance of the Sheffield Football Association was reflected in the selection of its treasurer, William Peirce Dix, as one of two delegates to represent England at the International Football Conference of December 1882. This meeting resulted in one unified set of rules for association football across Britain and Ireland. It prefigured the International Football Association Board, which would be the final authority on the laws of the game from 1886 onwards.[71]

Summary of principal changes in the laws

| Date | Size of Goal | Tie-breaker | Handling allowed | Offside law | Indirect free kick awarded for | Throw-in / kick-in | Goal-kick / "kick-out" | Corner-kick (defensive) | Corner-kick (attacking) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1858 | Unspecified | None[72] | Fair catch Pushing the ball Hitting the ball |

None | Fair catch | Throw-in awarded to first team to touch ball after it goes out of play. Must be thrown in at right angles to the touchline. | Whenever no goal scored | None | None |

| 1860 | Fair catch | ||||||||

| 1862 | 12 ft wide 9 ft high |

Rouge (requiring touchdown) | Whenever no goal or rouge scored | ||||||

| 1863 | One opponent must be level or closer to goalline | ||||||||

| 1865 | Any player ahead of the ball is offside[73] | ||||||||

| 1866 | One opponent must be level or closer to goalline | ||||||||

| 1867 (March) | Rouge (no touchdown required) | None | Handball | Throw-in awarded against team who kicked ball into touch. Must be thrown in at right-angles to the touchline. | Whenever no goal scored | ||||

| 1867 (October) | Whenever no goal scored, and ball goes directly above the crossbar | ||||||||

| 1868 | 24 ft wide 9 ft high |

None | Fair catch | Fair catch Handball Foul play |

Kick-in awarded against team who kicked ball into touch. May be kicked in any direction. | Whenever no goal scored, the ball was last touched by a member of the attacking team, and the ball did not go directly over the crossbar. | Whenever no goal scored, the ball was last touched by a member of the defending team, and the ball did not go directly over the crossbar. | ||

| 1869 | Fair catch Attempted catch Within 3 yards of goal |

Handball Foul play | |||||||

| 1871 | Within 3 yards of goal Hand not extended from body | ||||||||

| 1875 | 24 ft wide, 8 ft high | Within 3 yards of goal Hand not extended from body Defender closest to goal | |||||||

| 1876 | Goalkeeper, in defence of goal, provided ball not carried | Foul play | |||||||

| 1877 (FA Laws) |

Three opponents must be closer to goalline | Handball Offside Foul play |

Throw-in awarded against team who kicked ball into touch. May be thrown in any direction. | Whenever no goal scored, and the ball was last touched by a member of the attacking team | None | Whenever no goal scored, and the ball was last touched by a member of the defending team | |||

Early years

Initially the code was only played among Sheffield F.C. members.[74] Games initially teamed players with surnames in the first half of the alphabet against players with surnames in the latter half of the alphabet. They, however, discovered that the most talented players all had surnames in the first half. Various other permutations were tried with professionals versus merchants and manufacturers becoming one of the favourites. In December 1858 they played their first outside opposition, a team from the local 58th Army Regiment.

An early inter-club match between Sheffield and the newly formed Hallam F.C. took place on 26 December 1860. The match took place at Hallam's ground, Sandygate Road. It was reported that "The Sheffielders turned in their usual Scarlet and White" which suggests that club colours were already in use.[75] Despite playing with inferior numbers Sheffield F.C. beat Hallam 2–0. The game of the time could still be a violent one. A match on 29 December between Sheffield and Hallam became known as the Battle of Bramall Lane. An incident occurred when Nathaniel Creswick was being held by Shaw and Waterfall. Accounts differ over subsequent events. The original report stated that Creswick was accidentally punched by Waterfall. This was contested in a letter from the Hallam players that claimed that it was in retaliation for a blow thrown by Nathaniel Creswick. Whatever the cause the result was a general riot, which also involved a number of spectators, after which Waterfall was sent to guard the goal as punishment.[76]

Sheffield and London

The Football Association (FA) was formed at a meeting in the Freemason's Tavern in Great Queen Street, London on 26 October 1863. Sheffield F.C. sent four representatives who acted as observers.[77] The club joined the new organisation a month later in a letter sent by William Chesterman. In it he also enclosed a copy of the Sheffield Rules and expressed the club's opposition to hacking and running with the ball, describing them as "directly opposed to football". This letter was read out at an FA meeting on 1 December 1863. The rules allowing hacking and running with the ball were reversed at the same meeting.[78] The new code became known as Association Football. The FA had remained largely dormant after the creation of its rules but in 1866 Sheffield F.C. suggested a match between it and a FA club.[79] This was misunderstood and they ended up playing a combined FA team on 31 March 1866 under FA rules. The game was the first ever to limit the match to 90 minutes and Sheffield F.C. adopted it as its preferred length of match.[80] The rule would make it to the FA rule book in 1877. A second match was suggested by the London FA in a letter sent in November or the same year but never took place, the reason being disputes of which rules should be used.[81] The FA introduced an 8 feet (2.4 m) cross bar used by Sheffield in the same year only for Sheffield to then decide to raise it to 9 feet (2.7 m).[82] The fair catch was also dropped by Sheffield.[83] This completed the transition to a purely kicking game.

By 1867 the Sheffield Rules was the dominant code in England.[84] The FA had still not achieved the national dominance it enjoys today. Its membership had shrunk to just 10 clubs and at a meeting of the FA it was reported that only three clubs (No Names Club, Barnes and Crystal Palace) were playing by the FA code.[41] At the same meeting the secretary of Sheffield Club suggested three rule changes at an FA meeting: the adoption of rouges, the one man offside and introduction of a free kick for handling the ball. None of the motions were successful.[81] Later in the same year, they abolished handling and touchdowns. It was stated that this was to bring them closer to non-handling games.[85]

Birth of competition

| Wikisource has text of Sheffield Football Association laws from 1867 to 1876: |

In 1867 the world's first football tournament, the Youdan Cup, was played under the rules.[86] The tournament involved 12 local sides and was played during February and March. The tournament committee decided on the use of an off-field referee to award free kicks for infringements. The final took place on 5 March and was only the second football match to take place at Bramall Lane. A crowd of 3,000, a world record attendance, watched Hallam F.C. claim the cup by scoring two rouges in the last five minutes to win two rouges to one.[86] The Sheffield Football Association was founded following the tournament.[87] The 12 teams involved in the tournament were joined by Sheffield F.C. to become the founding members. The association adopted the Sheffield Rules without any changes. They were the first of several regional Football Associations that sprung up over the following decade.

A second tournament, the Cromwell Cup was played a year later.[88] This time it was only open to teams under two years old. Out of the four teams that competed The Wednesday emerged victorious. The final was a goalless draw after 90 minutes so the teams played on until a goal was scored. This was the first instance where a match involved extra time.[89] This would be the last tournament to be played in Sheffield for nine years until the formation of the Sheffield Football Association Challenge Cup in 1876.[90]

Between 1871 and 1876 a total of 16 matches were played between the Sheffield and London associations.[91] As well as playing under both Sheffield and London rules, additional matches were played at Bramall Lane using a mixture of both sets.

Demise

The FA Cup was inaugurated in 1871, but Sheffield clubs declined to enter the competition as it was being played under FA rules.[92] The first team to enter was Sheffield F.C. in the 1873–74 season. This was after an attempt to enter a Sheffield FA team was refused by the organisers. They reached the quarter-finals before being knocked out by Clapham Rovers. The Sheffield FA instituted their own Challenge Cup in 1876.[93] The cup was open to all the members of the SFA that now included many clubs outside the local area. The first final attracted a crowd of 8,000, twice as much as the FA Cup final in the same season. It was a record crowd for a cup match that would be held until the FA Cup of 1883. The match was between Heeley and Wednesday and resulted in a 2–0 win for the latter.[93]

By 1877 it was clear that the situation had become impractical. After letters were published in The Field deriding the state of affairs it was decided to unite the kicking game under one set of laws.[94] By this time the FA Cup had helped the FA gain a dominant position within the game.[95]

By the 1880s the influence of the Sheffield FA started to wane. Internal troubles began to surface with disputes between the SFA and a new rival association, Hallamshire F.A. The former, led by Charles Clegg, also fought a losing battle against the onset of professionalism.[96] By the middle of the decade several local clubs, including Sheffield and Hallam F.C., were in financial trouble.

Innovations

Heading, corner kicks and awarding free kicks for fouls were conceived in Sheffield games.[2] One of the most enduring rules of the Sheffield game prevented a goal from being scored directly from a free kick or throw in/kick in. This was present in every version of the Sheffield Rules and was later adopted within the FA rules.[97] It was later refined by the International Football Association Board into the modern-day indirect free kick.

The aerial game was also developed within the Sheffield game. While causing much amusement when the side visited London in 1866, the header would become an important feature of the national game.[98] This was linked to the abolition of the fair catch in the same year that prevented all use of the hands by outfield players.[83]

The 1862 rules also introduced a half-time at which the teams would swap ends.[26] Initially this was only if the game was scoreless as the teams would also swap ends if a goal was scored. The rule was changed to a swap at half-time only in 1876.[99]

Early games did not use any on-field officials but disputes between the players would be referred to a committee member.[100] Umpires were introduced by the end of 1862. Two umpires were used; one from each club. The off-field referee was introduced for the Youdan Cup in 1867 and entered the rulebook by 1871.[101] The umpires would then appeal to the referee on behalf of their team. The concept was later introduced to the FA game and persisted until 1891 when the referee moved onto the pitch and the umpires became linesmen. The umpire's flag was first suggested by Charles Clegg at a Sheffield FA meeting in 1874.[101]

The innovative streak within Sheffield remained after the demise of their own rules. On 15 October 1878 a crowd of 20,000 watched the first floodlit match at Bramall Lane.[102] The exhibition match was set up to test the use of the lights and was played between specially selected teams captained by the brothers William and Charles Clegg. William Clegg's team won 2–0. The experiment was repeated a month later at the Oval.

The concept of a penalty goal for fouls within 2 yards (1.8 m) of the goal was suggested at a Sheffield FA meeting in 1879.[69] The penalty would eventually make it into the rules by 1892. Sheffield players developed the 'screw shot' in the late 1870s. This gave players the ability to bend the shot into the net, a technique now common in the game.[103]

Legacy

Many of the rules in the Sheffield game were adopted by and are still featured in today’s association game. Twelve changes were made to the FA code between 1863 and 1870, of which eight were taken from Sheffield Rules.[104] During this period the Sheffield FA had significant influence over the FA and encouraged it to continue when it was close to collapse in 1867.[105] The corner kick was adopted by the FA in 1872 and they restricted handling of the ball to the goalkeeper's own half in 1873. In the final negotiations between Sheffield and London the latter agreed to allow throw-ins in any direction in exchange.[106]

During the 1860s Sheffield and London were the dominant football cultures in England.[107] However, while London was fragmented by the different codes used, by 1862 the rules of Sheffield F.C. had become the dominant code in Sheffield.[108] Nottingham Forest adopted the Sheffield code in 1867 and the Birmingham and Derbyshire FAs became affiliated with Sheffield, adopting its code, in 1876.[109]

There is circumstantial evidence that the rules also influenced Australian rules football conceived a couple of years later.[110] The two codes shared the unique feature of lacking the offside rule. There are also similarities in the laws for kicking off, kick outs, throw-ins and the fair catch, with the "behind" displaying some smilarities to the rouge.[111] Henry Creswick (possibly a relative of Nathaniel Creswick) was born in Sheffield but emigrated to Australia with his brother in 1840 (the town of Creswick is named after them). He moved to Melbourne in 1854 and became involved in the local cricket scene. He played first class cricket for Victoria during the 1857–1858 season alongside three of the founders of Melbourne Football Club including Tom Wills, the man credited with creating the original rules.

Despite the loss of their own rules, Sheffield remained a key part of the footballing world until the onset of professionalism.[112] Sheffield-born Charles Clegg became chairman of the Football Association in 1890 leading it until his death in 1937. In the process he became the longest serving FA chairman and earned the nickname "The Napoleon of Football".[113]

Formations, positioning and passing

Early games involved varying numbers of players. Games could also be played with uneven numbers on each side either because some failed to show or one side offered a handicap. The first match between Sheffield and Hallam involved 16 players versus 20. Games predominantly involved larger numbers than used in the modern games.[114] In October 1863, Sheffield declared that it would only play 11 a side matches.[39] Despite this it continued to do so on occasions. By 1867 the vast majority of matches in Sheffield involved teams of between 11 and 14.

One of the first positions to develop within the code was referred to as the "kick through".[115] The position was unique to the Sheffield game and developed because of the lack of an offside rule. The job of the man playing in the kick through position was to remain near to the opposition's goal and wait for a through ball, a tactic today called cherry picking or goal hanging.[115] By 1871 this position had become that of the modern-day striker. "Cover goals" developed in opposition to kick throughs. Despite their name their job was to man mark the kick through.

According to Charles W. Alcock, Sheffield provided the first evidence of the modern passing style known as the Combination Game.[114] In October 1863, Sheffield declared that they would only play 11-a-side matches.[39] As early as January 1865, Sheffield were said to have scored a goal through "scientific movements" against Nottingham.[116] A contemporary match report of November 1865 notes: "We cannot help recording the really scientific play with which the Sheffield men backed each other up"[117] Combination play by Sheffield players is also suggested in 1868: "a remarkably neat and quick piece of play on the part of K. Smith, Denton and J. Knowles resulted in a goal for Sheffield, the final kick being given by J. Knowles".[118]

Contemporary proof of passing occurs from at least January 1872. In January 1872 the following account is given against Derby: "W. Orton, by a specimen of careful play, running the ball up in close proximity to the goal, from which it was returned to J. Marsh, who by a fine straight shot kicked it through"[119] This play taking place "in close proximity to the goal" suggests a short pass and the "return" of the ball to Marsh suggests that this was the second of two passes. The account goes on to describe other interesting early tactics: "This goal was supplemented by one of T. Butler's most successful expositions of the art of corkscrew play and deceptive tactics which had the effect of exciting the risibility of the spectators"[119] Similarly the following contemporary account of passing comes from January 1872: "the only goal scored in the match was obtained by Sheffield, owing to a good run up the field by Steel, who passed it judiciously to Matthews, and the latter, by a good straight kick, landed it through the goal out of reach of the custodian".[120] That match (against Notts County) also provided contemporary evidence of "good dribbling and kicking" particularly by W. E. Clegg. The condition of the ground, however, "militated against a really scientific exhibition", suggesting that at other times their play was even more "scientific". Their play in March 1872 was described as "speed, pluck and science of no mean order".[121]

Before the introduction of the crossbar, teams could play without a goalkeeper.[122] The first reference to a goalkeeper appears in the report of the "Battle of Bramall Lane" in 1862.[123] The position, however, was used as an alternative to sending off a player. Although a recognised position goalkeeper sometimes was also referred to in the rules as the player nearest their own goal (allowing him the luxury of handling the ball). Unlike its FA counterpart Sheffield Rules never restricted handling to one designated player. Despite this by the 1870s teams usually featured a single player in the position.

The match between the Sheffield FA and the FA that took place in December 1871 is notable for evidence of the development of several new positions.[122] As well as the first mention of forwards, sides (now called wingers) were also mentioned. The rest of the team made up the midfield. The Half backs (referred to as centre backs in the modern game) were mentioned a year later. By the mid-1870s it was common to use one goalkeeper assisted by two cover goals and two half backs. The attack was made up of five midfielders and one forward. This produced the 2-2-5-1 formation.

Key figures

Nathaniel Creswick and William Prest are considered both founders of Sheffield F.C. and creators of the code they adhered to. They continued to have a strong presence at the club, both being members of the committee. It was Creswick, however, who exerted more influence over the rules in his position of Honorary Secretary and Treasurer.[124]

John Shaw was originally a member of Sheffield Club.[125] However another member, Thomas Vickers, also founded their main rivals, Hallam F.C. He also became the vice-president of the Sheffield FA upon its formation and president from 1869 to 1885. In this role he organised many of its first inter-association matches and was involved in the eventual merger of the Sheffield Rule into the national game.

Charles Clegg became a massive influence on the national as well as the local game.[126] As a player, he was involved in the first inter-association match and became the first Sheffield-based player to be capped (gaining his only cap in the first international). He went on to become president of both the city's professional sides (playing a large part in the creation of Sheffield United) and held the same position at Sheffield and Hallamshire FA having overseen the merger of the two rival local FAs. He then moved on to national prominence when he became chairman of the FA in 1890 and president in 1923. He held both positions until his death in 1937.

Although not directly involved with Sheffield football, Charles W. Alcock had a major role in relations between the local and London associations.[127] He acted as a go between encouraging the FA to accept rules from the Sheffield Rules. When the FA declined an inter-association match in Sheffield on the grounds that they could not play under Sheffield Rules it fell to Alcock to organise a team of London players to fulfil the fixture. The success of the match led to it becoming a regular event in the following years.

Notes

- "Meeting of the Sheffield Football Association". Sheffield and Rotherham Independent. lxi (5722): 7. 24 April 1877.

It was then formally resolved, ...that the Sheffield Association accept the Clydesdale Amendment and the London Rules"

- "Potting shed birth of oldest team". BBC. 24 October 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- Murphy, pp. 82–83.

- Farnsworth (Sheffield Football: A History), pp. 16–17.

- Murphy, p. 39.

- Young, pp. 15–17.

- Mangan, pp. 95–96.

- Harvey, Adrian (2004). The Beginnings of a Commercial Sporting Culture in Britain, 1793–1850. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Limited. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-75-463643-4.

- Murphy, pp. 38–39.

- Farnsworth (Sheffield Football: A History), pp. 21–22.

- Hutton, Curry & Goodman, p. 50.

- Tims, Richard (2011). "The Birth of Modern Football: The Earliest Rules and Historic Archive of the World's First Football Club". Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- Murphy, pp. 41–43.

- Curry and Dunning (2015), p. 49.

- Murphy, p. 47.

- Harvey (2005), pp. 95–100.

- Collins, Tony (2015). "Early Football and the Emergence of Modern Soccer, c. 1840–1880". International Journal of the History of Sport. 32 (9): 1131–1132. doi:10.1080/09523367.2015.1042868.

-

Sheffield Rules (1858) (first draft) Rugby School Rules (1851) 1. Kick off from Middle must be a place kick. i: Kick off from Middle must be a place-kick. 2. Kick out must not be from more than twenty five yards out of goal. ii: Kick out must not be from more than 25 yards out of goal, nor from more than 10 yards if a place-kick. 3. Fair Catch is a Catch direct from the foot of the opposite side and entitles a free kick. iii. Fair Catch is a catch direct from the foot. 4. Charging is fair in case of a place kick (with the exception of a kick off) as soon as the player offers to kick, but he may always draw back unless he has actually touched the Ball with his foot. iv: Charging is fair, in case of a place-kick, as soon as a ball has touched the ground; in case of a kick from a catch, as soon as the player offers to kick, but he may always draw back, unless he has actually touched the ball with his foot. 6. Knocking or pushing on the Ball is altogether disallowed. The side breaking this Rule forfeits a free kick to the opposite side. vii: Knocking on, as distinguished from throwing on, is altogether disallowed under any circumstances whatsoever.—In case of this rule being broken, a catch from such a knock on, shall be equivalent to a fair catch. 7. No player may be held or pulled over. xii: No player out of a maul may be held, or pulled over, unless he is himself holding the ball. 8. It is not lawful to take the Ball off the ground (except in touch) for any purpose whatever. viii: It is not lawful to take the ball off the ground, except in touch, either for a kick or throw on. 10. No Goal may be kicked from touch nor by a free kick from a catch. xx: No goal may be kicked from touch. 11. A ball in touch is dead. Consequently the side that touches it down, must bring it to the edge of the touch, & throw it straight out at least six yards from touch. xxi: Touch — A ball in touch is dead; consequently the first player on his side must in any case touch it down, bring it to the edge of touch, and throw it straight out. - "Sheffield F.C. – The Club". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- Murphy, p. 44.

- "Sheffield Foot-Ball Club". Sheffield Daily Telegraph: 2. 12 October 1859.

- – via Wikisource.

- Sheffield Football Club (1859). Rules, Regulations, & Laws of the Sheffield Foot-Ball Club, a list of members, &c. Sheffield: Pawson and Brailsford.

- Sheffield City Archives FCR/2; see also Murphy, p. 46.

- "Sheffield Football Club". Sheffield Daily Telegraph (1984): 5. 15 October 1861.

- Rules of Sheffield Football Club. Pawson and Brailsford. 1862.

- "Sheffield Football Club". Sheffield Daily Telegraph: 2. 31 January 1862.

- "Sheffield Football Club". Sheffield Daily Telegraph: 5. 8 February 1862.

- – via Wikisource.

- "Sheffield Football Club v. the 58th Regiment". Sheffield Daily Telegraph: 2. 20 December 1860.

- e.g. "Sheffield Football Club v. Hallam and Stumpelow Clubs". Sheffield Daily Telegraph: 2. 18 December 1860. "Sheffield Football Club v. Norton Football Club". Sheffield Daily Telegraph: 3. 28 November 1861.

-

Sheffield Rules (1862) Eton Field Game (1857) 11. A rouge is obtained by the player who first touches the ball after it has been kicked between the rouge flags, and when a rouge has been obtained one of the defending side must stand post two yards in front of the goal sticks. 5. A "rouge" is obtained by the player who first touches the ball after it has been kicked behind, or on the line of the goalsticks of the opposite side, provided the kicker has been "bullied" by one of more of the opposite party in the act of kicking. 12. No rouge is obtained when a player who first touches the ball is on the defending side. In that case it is a kick out as specified in law 2. 7. [...] should the ball be first touched by one of the defending party, no rouge is obtained, and the ball must be placed on a line with the goalsticks, and "kicked off" by one of that party. 13. No player who is behind the line of the goal sticks when the ball is kicked behind, may touch it in any way, either to prevent or obtain a rouge. 10. No player who is behind the line of the goalsticks, before the ball be kicked behind, may touch it in any way, either to prevent or obtain a rouge. 14. A goal outweighs any number of rouges. Should no goals or an equal number be obtained, the match is decided by rouges. 25. A goal outweighs any number of rouges, should no goals or an equal number be obtained, the match is decided by rouges. - Shearman, Montague (1887). Athletics and Football. London: Longman, Greens and Co. pp. 313–314.

[T]he defending side form down one yard from the centre of the goals by one of their number, called "post", taking up his position in the centre with the ball between his feet, and three or four placing themselves close up behind him, with others called "sides" on either side to support him ... On the attacking side, four players, also called sides, form down against the defenders' bully [scrummage]... two on either side, leaving a small gully in front of post just large enough to admit some four of the attacking side, and these headed by one who is said to run in charge in a compact mass, one close behind the other, against the centre of the opponents' bully, so that when they have closed, the whole is one consolidated mass. If the attacking side is stronger, and the sides do their work properly, the bully of the defenders is sometimes pushed bodily through goals; if, however, the two bullies are equal in weight or strength, the ball eventually breaks loose, and the play continues as originally begun.

- "Football: Sheffield v. Norton". Sheffield Daily Telegraph: 2. 24 February 1862.

- "The Yondam [sic] Football Cup". Bell's Life in London: 9. 9 March 1867.

- Chambers, Harry W. (9 February 1867). "[Correspondence]". The Field. xxix (737): 104.

- "The Football Association [letter from W. Chesterman, Hon. Sec. of Sheffield Football Club]". Supplement to Bell's Life in London. 5 December 1863. p. 1.

We have no printed rule at all like your No. 6 [the FA's draft offside law], but I have written in the book a rule which is always played by us.

- Tims, Richard (14 July 2011). "Catalogue note (Sheffield Football Club)". Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- Harvey (2005), pp. 118–119.

- A Correspondent (30 January 1867). "Football in Sheffield". The Sporting Life. London (826): 4.

- "The Football Association". Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chroncile (2288): 7. 24 February 1866.

- – via Wikisource.

- – via Wikisource.

- "Sheffield Football Association". The Sportsman: 4. 14 March 1867.

The laws of the General Association [i.e. the FA], as settled at the last meeting, were in each case taken as the proposition, and the laws of the game, as played at Sheffield, were moved as the amendments

- – via Wikisource.

- "Sheffield Football Association". Sportsman: 3. 12 November 1868.

- "Sheffield Football Association". Sheffield Daily Telegraph: 3. 14 October 1868.

- Alcock, Charles W. (ed.) (1871). The Book of Rules of the Game of Foot Ball. New York: Peck & Snyder. pp. 16–17.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Sparling, R. A. (6 May 1939). "Milestones in Memorable Campaign". The Star (Green 'Un). Sheffield: 8.

- "Sheffield Football Association". Sheffield and Rotherham Independent: 8. 9 October 1869.

- "Sheffield Football Association]". Sheffield Daily Telegraph: 3. 14 October 1869.

- "Sheffield Football Clubs Association". Sheffield and Rotherham Independent: 3. 24 January 1871.

- "Sheffield Football Association: Annual General Meeting". Sheffield and Rotherham Independent: 3. 12 October 1871.

- Sheffield Football Association (1875). The Laws of Football, as Re-Settled by the Sheffield Football Association, At the General Meeting, held at the Adelphi Hotel, February 25th, 1875. Season 1875-6. Sheffield: J. Robertshaw.

- "Sheffield Football Association". Sheffield Daily Telegraph: 3. 26 February 1875.

- "Sheffield Football Association". Sheffield and Rotherham Independent: 4. 26 February 1875.

- "Football Association". The Sportsman. London (1165): 6. 3 February 1872.

- "Football Association". The Sportsman. London (1181): 6. 2 March 1872.

- "The Football Association". The Sportsman. London (1387): 3. 27 February 1873.

- "The Football Association". Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle. London (2797): 9. 7 February 1874.

- "The Football Association". The Sportsman. London (1596): 3. 3 March 1874.

- "The London Football Association". Sheffield Daily Telegraph (6149): 7. 25 February 1875.

- "Sheffield Football Association". Sheffield Daily Telegraph: 3. 26 February 1875.

- "Football Notes". Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle. London (2905): 5. 4 March 1876.

- "The Football Association". Nottinghamshire Guardian (1649): 7. 2 March 1877.

- White Surrey (2 March 1877). "The Football Association Meeting [letter to the editor]". The Sportsman (2323): 4.

- – via Wikisource.

- "Meeting of the Sheffield Football Association". Sheffield and Rotherham Independent. lxi (5722): 7. 24 April 1877.

- Murphy, p. 107.

- "Sheffield Football Association". Sheffield Daily Telegraph (7386): 7. 18 February 1879.

- "History of IFAB". Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- No tie-breaker in the printed laws, but Sheffield FC used the rouge in one game in December 1860; see above for details

- Not played in all matches: see above for details

- Farnsworth (Sheffield Football: A History), p. 23.

- "Local and General Intelligence". Sheffield Daily Telegraph. 28 December 1860.

- Young, pp. 18–19.

- Hutton, Curry & Goodman, pp. 31–32.

- "1863 – The FA Forms". AFS Enterprises Limited. Retrieved 15 January 2008.

- Harvey (2005), p. 116.

- Murphy, p. 67.

- Young, p. 23.

- Murphy, p. 70.

- Harvey (2005), p. 122.

- Murphy, p. 66.

- Harvey (2005), p. 165.

- Murphy, pp. 77–78, 117.

- Murphy, pp. 101–102, 106.

- Farnsworth (Wednesday!), pp. 12–13.

- Murphy, p. 79.

- Farnsworth (Wednesday!), p. 18.

- Young, pp. 28–29.

- Hutton, Curry & Goodman, pp. 35–36.

- Murphy, pp. 121–122.

- Young, pp. 15–16.

- Murphy, pp. 105–106.

- Farnsworth (Sheffield Football: A History), pp. 29, 50–51.

- The Football Association (1881). The National Football Calendar for 1881. The Cricket Press. p. 3.

- "Sheffield F.C.: 150 years of history". FIFA. 24 October 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- Young, p. 40.

- Murphy, pp. 43, 57.

- Murphy, p. 117.

- Barrett, Norman (1996). The Daily Telegraph Football Chronicle. London: Random House. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-09-185234-4.

- "Part 12 of the History of Football". AFS Enterprises Limited. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- Mangan, p. 112.

- Harvey (2005), p. 125.

- Murphy, p. 106.

- Harvey, Adrian (2001). "An Epoch in the Annals of National Sport: Football in Sheffield and the Creation of Modern Soccer and Rugby". The International Journal of the History of Sport. Abingdon: Routledge. 18 (4): 53–87. doi:10.1080/714001668. PMID 18578082. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- Harvey (2005), pp. 92, 116.

- Murphy, pp. 69, 106.

- Murphy, pp. 39–41.

- Murphy, p. 68.

- Ward, Andrew (2000). Football's Strangest Matches. London: Robson Books Ltd. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-86-105292-6.

- Cox, Richard; Vamplew, Wray; Russell, David (2002). Encyclopedia of British Football. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-71-465249-8.

- Murphy, p. 59.

- Murphy, pp. 65, 82.

- "London v. Sheffield report". Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle. London (2229). 7 January 1865.

The Sheffield party, however, eventually took a lead, and through some scientific movements of Mr J. Wild, scored a goal amid great cheering.

- "[match report]". Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle. London (2275). 26 November 1865.

- "[match report]". Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle. London (2390). 8 February 1868.

- The Derby Mercury (Derby, England), Wednesday, 17 January 1872; Issue 8218.

- "[match report]". Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle. London (2691). 27 January 1872.

- "[match report]". Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle. London (2697). 9 March 1872.

- Murphy, p. 82.

- "Football Match at Bramall Lane". Sheffield and Rotherham Independent. 1 January 1863.

- Hutton, Curry & Goodman, p. 25.

- Murphy, pp. 52, 102.

- Farnsworth (Wednesday!), pp. 15–17.

- Murphy, pp. 69, 94.

References

- Curry, Graham; Dunning, Eric (2015). Association Football: A Study in Figurational Sociology. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-82851-3.

- Farnsworth, Keith (1995). Sheffield Football: A History. Volume 1, 1857–1961. Sheffield: Hallamshire Press. ISBN 978-1-87-471813-0.

- Farnsworth, Keith (1982). Wednesday!. Sheffield: Sheffield City Libraries. ISBN 978-0-90-066087-0.

- Harvey, Adrian (2005). Football: the First Hundred Years. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41-535019-8.

- Hutton, Steve; Curry, Graham; Goodman, Peter (2007). Sheffield FC. At Heart Limited. ISBN 978-1-84-547174-3.

- Mangan, J. A. (1999). Sport in Europe: Politics, Class, Gender. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-71-464946-7.

- Murphy, Brendan (2007). From Sheffield with Love. Garden City, Deeside: Sports Book Limited. ISBN 978-1-89-980756-7.

- Young, Percy M. (1964). Football in Sheffield. San Francisco: Dark Peak. ISBN 978-0-95-062724-3.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

.svg.png)