Mines in the Battle of Messines (1917)

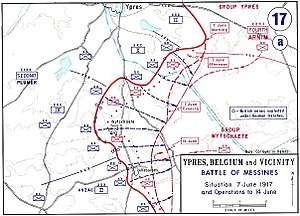

At the start of the Battle of Messines (7–14 June 1917) during the First World War, a series of underground explosive charges were detonated by the British Army beneath German lines near the village of Mesen (Messines in French, historically used in English), in Belgian West Flanders. The mines, secretly planted by British tunnelling units, created 19 large craters and are estimated to have killed approximately 10,000 German soldiers. Their joint explosion ranks among the largest non-nuclear explosions of all time.

The evening before the attack, General Sir Charles Harington, Chief of Staff of the Second Army (General Sir Herbert Plumer), remarked to the press, "Gentlemen, I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography".[1] The Battle of Messines marked the zenith of mine warfare. On 10 August, the Royal Engineers fired the last British deep mine of the war, at Givenchy-en-Gohelle near Arras.[lower-alpha 1]

Background

British mining, 1915–1916

As part of allied operations in the Ypres Salient, British mining against the German-held salient at Wijtschate near Messines had begun in early 1915, with diggings 4.6–6.1 metres (15–20 ft) below the surface.[3][lower-alpha 2] The concept of a deep mining offensive was devised in September 1915 by the Engineer-in-Chief of the BEF, Brigadier George Fowke, who proposed to drive galleries 18–27 metres (60–90 ft) underground. Fowke had been inspired by the thinking of Major John Norton-Griffiths, a civil engineer, who had helped form the first tunnelling companies and introduced the quiet clay kicking technique.[3]

In September, Fowke proposed to dig under the Ploegsteert–Messines (Mesen), Kemmel–Wytschaete (Wijtschate) and Vierstraat–Wytschaete roads and to dig two tunnels between the Douve river and the south-east end of Plugstreet (Ploegsteert) Wood, the objectives to be reached in three to six months. Fowke had wanted galleries about 960 metres (1,050 yd) long, as far as Grand Bois and Bon Fermier Cabaret on the fringe of Messines but the longest tunnel was a 660 metres (720 yd) gallery to Kruisstraat.[3] The scheme devised by Fowke was formally approved on 6 January 1916, although Fowke and his deputy, Colonel R. N. Harvey, had already begun the preliminaries. By January, several deep mine shafts, marked as "deep wells" and six tunnels had thus been started.[4] Sub-surface conditions were especially complex and separate ground water tables made mining difficult. To overcome the technical difficulties, two military geologists assisted the miners from March, including Edgeworth David, who planned the system of mines.[5][6]

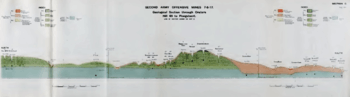

Co-ordinated by the Royal Engineers, the mine galleries were dug by the British 171st, 175th and 250th Tunnelling companies and the 1st Canadian, 3rd Canadian and 1st Australian Tunnelling companies, while the British 183rd, 2nd Canadian and 2nd Australian Tunnelling companies built dugouts (underground shelters) in the Second Army area.[7] Sappers dug the tunnels into a layer of "blue clay" 24–37 metres (80–120 ft) below the surface, then drifted galleries (horizontal passages) for 5,453 metres (5,964 yd) to points beneath the position of the German Group Wytschaete, despite German counter-mining.[8][9][lower-alpha 3] German tunnellers came within metres of several British mine chambers and, well before the Battle of Messines, found La Petite Douve Farm mine.[11] On 27 August, the Germans set a camouflet, which killed four men and wrecked the chamber for 120 metres (400 ft); the mine had been charged and the explosives were left in the gallery. A gallery of the Kruisstraat mine, begun on 2 January, had been dug for 690 metres (750 yd) and was flooded by a camouflet explosion in February 1917, after which a new chamber was dug and charged next to the flooded mine.[12] The British diverted the attention of German miners from their deepest galleries by making many minor attacks in the upper levels.[13]

Prelude

British mining, 1917

The BEF miners eventually completed a line of deep mines under Messines Ridge that were charged with 454 tonnes (447 long tons) of ammonal and gun cotton.[8] Two mines were laid at Hill 60 on the northern flank, one at St Eloi, three at Hollandscheschur Farm, two at Petit Bois, single mines at Maedelstede Farm, Peckham House and Spanbroekmolen, four at Kruisstraat, one at Ontario Farm and two each at Trenches 127 and 122 on the southern flank.[14][15] A group of four mines was placed under the German strongpoint Birdcage at Le Pelerin, just outside Ploegsteert Wood. The large mines were at St Eloi, charged with 43,400 kilograms (95,600 lb) of ammonal, at Maedelstede Farm, which was charged with 43,000 kilograms (94,000 lb), and Spanbroekmolen on one of the highest points of the Messines Ridge, which was filled with 41,000 kilograms (91,000 lb) of ammonal. The mine at Spanbroekmolen was set 27 metres (88 ft) below ground, at the end of a gallery 520 metres (1,710 ft) long.[16]

When detonated on 7 June 1917, the blast of the mine at Spanbroekmolen formed the "Lone Tree Crater" with a diameter of 76 metres (250 ft) and a depth of 12 metres (40 ft).)[16] The mine at Ontario Farm did not produce a crater but left a shallow indentation in the soft clay, after wet sand flowed back into the crater.[12][17][18] Birdcage 1–4 on the extreme southern flank in the II Anzac Corps area, were not required because the Germans made a local retirement before 7 June. Peckham 2 was abandoned due to a tunnel collapse and the mine at La Petite Douve Farm was abandoned after the German camouflet blast of 27/28 August 1916. The evening before the attack, Harington, the Second Army Chief of Staff, remarked to the press, "Gentlemen, we may not make history tomorrow, but we shall certainly change the geography".[19]

German mining, 1916–17

In December 1916, Oberstleutnant Füßlein, commander of German mining operations in the salient, had recorded that British deep mining was intended to support an offensive above ground and received three more mining companies, to fight in the British lower as well as the upper mine systems and had gained some success. In April 1917, the 4th Army (General Friedrich Bertram Sixt von Armin) received information from air reconnaissance that a British offensive was being prepared in the Messines Ridge sector and a spy reported to OHL, that if the offensive at Arras was frustrated, the British would transfer their effort to Flanders. Hermann von Kuhl, the Chief of Staff of Heeresgruppe Kronprinz Rupprecht (Army Group Crown Prince Rupprecht), suggested that the salient around Messines Ridge be abandoned, since it could be attacked from three sides and most of the defences were on forward slopes, vulnerable to concentric, observed artillery-fire. A voluntary retirement would avoid the calamity experienced by the defenders at the Battle of Vimy Ridge on 9 April.[20]

Kuhl proposed a retirement to the Sehnen Line (Oosttaverne Line to the British), halfway back from the Second Line along the ridge or all the way back to the Third Line (Warneton Line). At a conference with 4th Army commanders to discuss the defence of Messines Ridge on 30 April, most of them rejected the suggestion, because they considered that the defences had been modernised, were favourable for a mobile defence and convenient for counter-attacks. The artillery commander of Gruppe Wijtschate said that the German guns were well-organised and could overcome British artillery.[20] The divisional commanders were encouraged by a report by Füßlein on 28 April, that the counter-mining had been such a success, particularly recently that

A subterranean attack by mine-explosions on a large scale beneath the front line to precede an infantry assault against the Messines Ridge was no longer possible. (nicht mehr möglich)

— Colonel Füßlein[20]

For this and other reasons the withdrawal proposal was dropped as impractical (nicht tünlich). Soon after the conference, Füßlein changed his mind and on 10 May, reported to the 4th Army his suspicions that the British might have prepared several deep mines, including ones at Hill 60, Caterpillar, St. Eloi, Spanbroekmolen and Kruisstraat and predicted that if an above-ground offensive began, there would be big mine explosions in the vicinity of the German front line.[21]

On 19 May, the 4th Army concluded that the greater volume of British artillery fire was retaliation for the increase in German bombardments and although defensive preparations were to continue, no attack was considered imminent.[21] On 24 May, Füßlein was more optimistic about German defensive measures and Laffert wrote later, that the possibility of mine explosions was thought remote and if encountered they would have only local effect, as the front trench system was lightly held. From 12 May, weekly reports by the 4th Army made no mention of mining and Rupprecht made no reference to it after the end of the month. Other officers like Oberstleutnant Wetzell and Oberst Fritz von Lossberg, wrote to OHL warning of the mine danger and the importance of forestalling it by a retirement and were told that it was a matter for the commanders on the spot.[22]

Battle: 7 June 1917

The artillery fire was lifted half an hour before dawn, and as they waited in the silence for the offensive to begin, some of the troops reportedly heard a nightingale singing.[23] Starting from 3.10 a.m. on 7 June, the mines at Messines were fired within the space of 20 seconds. The joint explosion ranks among the largest non-nuclear explosions of all time and surpassed the mines on the first day of the Somme fired 11 months before. The sound of the blast was considered the loudest man-made noise in history. Reports suggested that the sound was heard in London and Dublin, and at Lille University's geology department, the shock wave was mistaken for an earthquake. Some eyewitnesses described the scene as "pillars of fire", although many also conceded that the scene was indescribable.[24]

Suddenly at dawn, as a signal for all of our guns to open fire, there rose out of the dark ridge of Messines and "Whitesheet" and that ill-famed Hill 60, enormous volumes of scarlet flame [...] throwing up high towers of earth and smoke all lighted by the flame, spilling over into fountains of fierce colour, so that many of our soldiers waiting for the assault were thrown to the ground. The German troops were stunned, dazed and horror-stricken if they were not killed outright. Many of them lay dead in the great craters opened by the mines.

The fact that the detonations were not simultaneous enhanced their effect on the German troops. Strange acoustic effects also added to the panic – German troops on Hill 60 thought that the Kruisstraat and Spanbroekmolen mines were under Messines village, which was located well behind their front line, while some British troops thought that they were German counter-mines going off under the British support trenches.[23] The combined explosion is considered to have killed more people than any other non-nuclear man-made explosion in history; it killed approximately 10,000 German soldiers between Ypres and Ploegsteert.[23]

Aftermath

Two days after the battle, the Gruppe Wijtschate commander General Maximilian von Laffert was sacked. The German official history report, Der Weltkrieg (volume XII, 1939), placed the mines, which were unprecedented in size and number, second in a list of five reasons for the German defeat. In an after-action report, Laffert wrote that had the extent of the mine danger been suspected, a withdrawal from the front trench system to the Sonne Line, halfway between the First and Second lines, would have been ordered before the attack, since the cost inflicted on the British by having to fight for the ridge justified its retention.[26] In 1929, Hermann von Kuhl lamented the failure to overrule the 4th Army commanders on 30 April and prevent "one of the worst tragedies of the war".[27]

The Battle of Messines was regarded as the most successful local operation of the war but it left a legacy: six mines were not used. Four on the extreme southern flank were not required because the ridge fell so quickly, and another, a 20,000-pound (9,100 kg) mine codenamed Peckham, was abandoned before the attack due to a tunnel collapse. The sixth, and one of the biggest, was planted under a ruined farm called La Petite Douve. It was lost when the Germans mounted a counter-mining attack, and never used. After the war, La Petite Douve was rebuilt by its owners, the Mahieu family, and later renamed La Basse Cour. The mine is beneath a barn, next to the farmhouse.

— Neil Tweedie[15]

List of the mines

| No. | Name / Location |

Position | Explosive charge[28] |

Tunnel length[28] |

Depth[28] | Constructed | Result | Notes and images (May be under first row of each group of mines) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hill 60 (or Hill 60 A) | 50°49′26″N 2°55′44″E | 24,300 kg (53,500 lb) | 354 m | 30 m | 22 August 1915 – 1 August 1916 | Fired | Shared gallery with Caterpillar, started in mid-1915 as one of the first allied mines at Ypres and known as Berlin Tunnel. By June 1917, the mine consisted of a main gallery leading to two separate mine chambers (Hill 60 A and Hill 60 B).[29] See note:[lower-alpha 4]

|

| 2 | Caterpillar (or Hill 60 B) | 50°49′20″N 2°55′43″E | 32,000 kg (70,000 lb) | 427 m | 33 m | 22 August 1915 – 18 October 1916 | Fired | Views: aerial view, photo |

| 3 | St Eloi | 50°48′32″N 2°53′31″E | 43,400 kg (95,600 lb) | 408 m | 42 m | 16 August 1915 – 11 June 1916 | Fired | Largest detonation during the Battle of Messines.[32] The deep mine crater is located next to double crater from 1916.[18]

See note:[lower-alpha 5]

|

| 4 | Hollandscheschur Farm 1 | 50°47′50″N 2°52′10″E | 15,500 kg (34,200 lb) | 251 m | 20 m | 18 December 1915 – 20 June 1916 | Fired | The mine consisted of three chambers (Hollandscheschur Farm 1–3) with a shared gallery.[32] It was placed around the German strongpoint Günther between Wijtschate and Voormezele, not far from the Bayernwald trenches in Croonaert Wood. See note:[lower-alpha 6]

|

| 5 | Hollandscheschur Farm 2 | 50°47′49″N 2°52′04″E | 6,800 kg (14,900 lb) | 137 m | 18 m | 18 December 1915 – 11 July 1916 | Fired | |

| 6 | Hollandscheschur Farm 3 | 50°47′53″N 2°52′05″E | 7,900 kg (17,500 lb) | 244 m | 18 m | 18 December 1915 – 20 August 1916 | Fired | |

| 7 | Petit Bois 1 | 50°47′18″N 2°51′56″E | 14,000 kg (30,000 lb) | 616 m | 19 m | 16 December 1915 – 30 July 1916 | Fired | The mine consisted of two chambers (Petit Bois 1 and 2) with a shared gallery.[32] It was placed west of Wijtschate. See note:[lower-alpha 7]

|

| 8 | Petit Bois 2 | 50°47′22″N 2°51′56″E | 14,000 kg (30,000 lb) | 631 m | 23 m | 16 December 1915 – 15 August 1916 | Fired | |

| 9 | Maedelstede Farm | 50°46′59″N 2°51′57″E | 43,000 kg (94,000 lb) | 518 m | 33 m | 3 September 1916 – 2 June 1917 | Fired | Two chambers (Wytschaete Wood and Maedelstede Farm) were planned, but lack of time prevented the former from being finished and all effort was concentrated the latter.[33][18] It was placed west of Wijtschate. See note:[lower-alpha 8]

|

| 10 | Peckham 1 | 50°46′47″N 2°51′50″E | 39,000 kg (87,000 lb) | 349 m | 23 m | 20 December 1915 – 19 June 1916 | Fired | The mine consisted of two chambers (Peckham 1 and 2) with a shared gallery. Peckham 1 was detonated during the battle.[33] Peckham 2 was placed under a farm building[15][18] but abandoned after the tunnel flooded.[33] See note:[lower-alpha 9]

|

| 11 | Peckham 2 | 50°46′52″N 2°51′56″E | 9,100 kg (20,000 lb) | 122 m | 23 m | 20 December 1915 – December 1916 | Abandoned | |

| 12 | Spanbroekmolen (or Lone Tree Crater, Pool of Peace) | 50°46′33″N 2°51′42″E | 41,000 kg (91,000 lb) | 521 m | 29 m | 1 January 1916 – 26 June 1916 | Fired | Discovered by German troops in February 1917, later reclaimed and fired in the Battle of Messines.[17] The crater was acquired in 1929 by the Toc H foundation in Poperinge, today recognised as peace memorial.[17][18][35] See note:[lower-alpha 10]

|

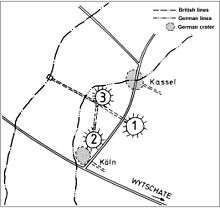

| 13 | Kruisstraat 1 | 50°46′16″N 2°51′54″E | 14,000 kg (30,000 lb) | 492 m | 19 m | 2 January 1916 – 5 July 1916 | Fired | Building preparations for a two-chamber mine started in December 1915. Kruisstraat 1 was placed at the end of a 492 metres (538 yd) long gallery, Kruisstraat 2 some 50 metres (55 yd) to its right. Kruisstraat 3 was added two months later and Kruisstraat 4 in 1917. Two craters remain, which seem to have been caused by the first and second charges.[36][37] Kruisstraat 1 and 4 shared a gallery and were fired together.[18][38] See note:[lower-alpha 11]

|

| 14 | Kruisstraat 2 | 50°46′14″N 2°51′52″E | 14,000 kg (30,000 lb) | 451 m | 21 m | 2 January 1916 – 23 August 1916 | Fired | |

| 15 | Kruisstraat 3 | 50°46′21″N 2°52′2″E | 14,000 kg (30,000 lb) | 658 m | 17 m | 2 January 1916 – 23 August 1916 | Fired | Kruisstraat 3 had the longest gallery of the mines at Messines. |

| 16 | Kruisstraat 4 | 50°46′16″N 2°51′54″E | 8,800 kg (19,500 lb) | 492 m | 19 m | February 1917 – 9 May 1917 | Fired | |

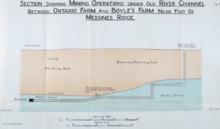

| 17 | Ontario Farm | 50°45′50.4″N 2°52′36.9″E | 27,000 kg (60,000 lb) | 392 m | 34 m | 28 January 1917 – 6 June 1917 | Fired | The mine did not produce a crater but left a shallow indentation in the soft clay; the shock wave did great damage to the German position.[17][18] It was placed west of Mesen (Messines). See note:[lower-alpha 12] |

| 18 | La Petite Douve Farm | 50°45′20.6″N 2°53′36.9″E | 23,000 kg (50,000 lb) | 518 m | 23 m | 28 January 1916 – n/a | Abandoned | The mine was placed under the barn of the farm La Basse Cour.[15] It was discovered by the Germans on 24 August 1916, then flooded and abandoned.[17][18][40] See note:[lower-alpha 13] |

| 19 | Trench 127 Left (or Trench 127 North) | 50°44′55″N 2°54′14″E | 16,000 kg (36,000 lb) | 302 m | 25 m | 28 December 1915 – 20 April 1916 | Fired | The mine consisted of two chambers (Trench 127 Left and Right) with a shared gallery. It was placed east of St. Yvon (St. Yves). The crater was in a field near the Khaki Chums Cross memorial and filled in during the latter part of the 20th century.[43][44][45][18] See note:[lower-alpha 14] |

| 20 | Trench 127 Right (or Trench 127 South, Ash Crater)[46] | 50°44′51″N 2°54′17″E | 23,000 kg (50,000 lb) | 405 m | 26 m | 28 December 1915 – 9 May 1916 | Fired | |

| 21 | Trench 122 Left (or Factory Farm 1, Ultimo Crater)[46][18][44][47] | 50°44′36″N 2°54′45″E | 9,100 kg (20,000 lb) | 296 m | 20 m | February 1916 – 14 April 1916 | Fired | The mine consisted of two chambers (Trench 122 Left and Right) with a shared gallery. It was placed east of St. Yvon (St. Yves). Preparations for a two-chamber mine extending from Trench 122 started in December 1915. A charge of 9,100 kilograms (20,000 lb) was laid in May 1916 and a second of 18,000 kilograms (40,000 lb) was placed at the end of a 200 metres (220 yd) long gallery, beneath the derelict Factory Farm.[45] See note:[lower-alpha 15]

|

| 22 | Trench 122 Right (or Factory Farm 2, Factory Farm Crater)[46][18][44][47] | 50°44′30″N 2°54′47″E | 18,000 kg (40,000 lb) | 241 m | 25 m | February 1916 – 11 June 1916 | Fired | Views: photo 1, photo 2 |

| 23 | Birdcage 1 (or Trench 121) | 50°44′21″N 2°54′27″E | 9,100 kg (20,000 lb) | 130 m | 18 m | December 1915 – 7 March 1916 | Not fired[15] | The mine was placed east of Ploegsteert, around the German strongpoint Birdcage at Le Pelerin, near the southern end of Messines Ridge.[47] Five mines were planned here, of which four (Birdcage 1–4) were constructed.[48] None of them was fired, as they were too far behind British lines by the time the Battle of Messines commenced.[18][46][49] |

| 24 | Birdcage 2 (or Trench 121) | 50°44′20″N 2°54′28″E | 15,000 kg (32,000 lb) | 236 m | 18 m | December 1915 – n/a | Not fired | |

| 25 | Birdcage 3 (or Trench 121) | 50°44′20″N 2°54′31″E | 12,000 kg (26,000 lb) | 261 m | 20 m | December 1915 – 30 April 1916 | Exploded in 1955 |

Detonated by lightning on 17 June 1955, after an electric-power pylon had been built over the site.[50][17] |

| 26 | Birdcage 4 (or Trench 121) | 50°44′20″N 2°54′30″E | 15,000 kg (34,000 lb) | 239 m | 18 m | December 1915 – n/a | Not fired |

Gallery

- Crater of the 1917 deep mine fired at Caterpillar

- Crater of the 1917 deep mine fired at Hill 60

Access the Berlin Tunnel leading to the Hill 60 and Caterpillar deep mines

Access the Berlin Tunnel leading to the Hill 60 and Caterpillar deep mines Crater of the 1917 deep mine fired at Spanbroekmolen

Crater of the 1917 deep mine fired at Spanbroekmolen- View from Spanbroekmolen crater towards the Kruisstraat craters

- Crater of the 1917 deep mine fired at Kruisstraat, view towards the Spanbroekmolen crater

See also

- Mining (military)

- Battle of Messines (1917)

- Beneath Hill 60 (film)

- Mines on the first day of the Somme

- Mines on the Italian Front (World War I)

Notes

- Around 7:05 a.m., the 251st Tunnelling Company on the 5th Infantry Brigade front of the 2nd Division, exploded a mine at the northern end of the brigade sector, near Surrey Crater, which became known as Warlingham Crater.[2]

- Belgian place names changed in the 20th century and British versions such as "Wytschaete" (Whitesheet) often retain the old French-inspired spellings and pronunciations, which have been superseded in official Belgian usage.

- German corps were detached from their component divisions on 3 April 1917 and given permanent areas to hold, under a geographical title. Gruppe Wijtschate was based on the XIX Corps headquarters (General Maximilian von Laffert) and controlled the 204th Division, 35th Division, 2nd Division and the 40th Division.[10]

- The early underground war in the area had involved both the 171st and 172nd Tunnelling Company. After the Battle of Hill 60 in April and May 1915, the Royal Engineers took up mining operations under the hill and the neighbouring ground on a much more ambitious scale. Deep mining under German galleries beneath Hill 60 started in August 1915 with 175th Tunnelling Company, which began a gallery 200 metres (220 yd) behind the British front line and passed 27 metres (90 ft) beneath the German positions. The British underground works consisted of an access gallery (nicknamed Berlin Tunnel) leading to two mine chambers called Hill 60 A (beneath Hill 60) and Hill 60 B (beneath The Caterpillar). 3rd Canadian Tunnelling Company took over in April 1916 and completed the galleries, Hill 60 A being charged with explosives in July 1916 and the Hill 60 B branch gallery in October. By October 1916, Hill 60 A had been charged with 24,200 kilograms (53,300 lb) of explosives and Hill 60 B with 32,000 kilograms (70,000 lb) of high explosive, despite water-logging and the demolition by a camouflet of 61 metres (200 ft) of German gallery above the British diggings, which endangered the British deep mines. 1st Australian Tunnelling Company took over in November 1916 and maintained the completed mines beneath Hill 60 and The Caterpillar over the winter and months of underground fighting until June 1917, when they were fired at the beginning of the Battle of Messines. When the mines were fired, the detonations demolished a large part of Hill 60 and killed c. 10,000 German soldiers between Ypres and Ploegsteert. Fifteen miles away in Lille, German troops ran around "panic-stricken". Odd acoustic effects also increased the shock and Germans on Hill 60 thought that the Kruisstraat and Spanbroekmolen mines were under Messines village, well behind their front line; some British troops thought that they were German counter-mines, going off under British support trenches.[30][31]

- Mining activity by the tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers had begun at St Eloi in early 1915. Much of the mining in this sector was done by the 177th Tunnelling Company and the 172nd Tunnelling Company, the latter commanded by Captain William Henry Johnston VC. Mining and counter-mining at St Eloi continued at a pace and in the planning for the Battle of Messines it was decided that tunnelling for a deep mine at St Eloi would have to start some distance away. The work was begun with a deep shaft named Queen Victoria and the chamber was set 42 metres (138 ft) below ground, at the end of a gallery 408 metres (1,339 ft) long and charged with 43,400 kilograms (95,600 lb) of ammonal, the largest single charge of explosive used during the whole war.[32] (According to Holt and Holt, the Queen Victoria shaft was begun in the area of Bus House Cemetery, behind a farm-house called Bus House by the British troops 50°48′46.8″N 2°53′13.6″E.) From there, the gallery was extended to the area of the mine chamber.[32] When the St Eloi deep mine exploded, it destroyed several of the craters created by the six British mines fired below German lines on 27 March 1916.

- In November 1915, the 250th Tunnelling Company began work on the deep mine at Hollandscheschur Farm as it sank a shaft to some 20 metres (66 ft) and then drove a tunnel over 250 metres (820 ft) extending well behind the German lines. Despite counter-mining by German units, three charges were eventually placed and fired. The logic behind the exact placing of the charges at Hollandscheschur Farm was to take out a small German salient (strongpoint Günther) that protruded into the British lines.[32]

- December 1915, 250th Tunnelling Company began work on the deep mine at Petit Bois. Tunnelling began about 170 m behind the British forward lines and first went down over 30 metres (98 ft). As with many deep mines, compressed air and electricity were supplied from the surface. The tunnellers experimented with a mechanical excavator operated by hydraulic rams, similar to those used for the London Underground. The device weighed more than half a ton and promised to cut a tunnel about 2 metres (6.6 ft) in diameter. In March 1916 it was used to dig 5 metres (16 ft) but developed difficluties and was abandoned in situ. The main gallery of the Petit Bois mine was taken out by clay kicking over 500 metres (1,600 ft) and reached beyond the German lines when it was breached by enemy counter-mining. When the enemy blew a camouflet, 12 men were trapped by a collapsed tunnel over 30 metres (98 ft) below the surface. After six days, the British tunnellers managed to rescue Sapper William Bedson, a veteran of the Ypres Salient and of Gallipoli. When completed, the main gallery leading to the two mine chambers was more than 600 metres (2,000 ft) long.[32]

- This deep mine was begun by 250th Tunnelling Company[34] at the end of 1916 and forward workings started at a depth of about 45 metres (148 ft). One tunnel headed towards Wytschaete Wood and the other towards Maedelstede Farm over 500 metres (1,600 ft) away. In order to remove the spoil from the workings, a covered tramway was built running back behind the British lines where the spoil was camouflaged to prevent detection of the mining activities by the Germans. When it was realised that Wytschaete Wood could not be reached in time, all efforts were concentrated upon the branch tunnel heading for Maedelstede Farm. The explosive was put in place, tested and ready to fire just 24 hours before the start of the Battle of Messines.[33]

- The shaft for the deep mine at Peckham Farm was begun by 250th Tunnelling Company on 18 December 1915 and sunk to 20 metres (66 ft), the heavy clay requiring much timber as the tunnel was driven forward to the German lines. Despite strenuous efforts to work as silently as possible, including the use of the 'clay kicking' method, German trench mortar activity caused many delays and flooding swamped much of the work, causing several earlier tunnels to be abandoned. The main charge was eventually placed below Peckham Farm as planned and in time, some 400 metres (1,300 ft) from where the digging had started.[33]

- The Spanbroekmolen mine was located on one of the highest points of the Messines Ridge and named after a windmill that stood on the site for three centuries until it was destroyed by the Germans on 1 November 1914. In order to start a mine gallery, the tunnellers looked for some cover under which to dig a vertical shaft from which the tunnel could be driven forward towards the enemy lines. At Spanbroekmolen, the start point for the tunnel was in the area of a small wood some 270 metres (300 yd) to the south-west. In December 1915, 250th Tunnelling Company dug a 18 metres (60 ft) shaft and then handed over the work to 3rd Canadian Tunnelling Company in January 1916. Other operating changes occurred until 171st Tunnelling Company took over and extended the work to the German lines at Spanbroekmolen, having driven the tunnel forward by 523 metres (1,717 ft) in seven months. In February 1917 German counter mining activities damaged the main tunnel so the British dug a recovery gallery which after 357 metres (1,172 ft) cut into the original tunnel and allowed the Royal Engineers to rescue the mine. A long branch gallery for another mine at Spanbroekmoelen was also started, but had to be abandoned in order to rescue the main tunnel. Mining was greatly hampered by the influx of gas, several miners being overcome by the fumes, but eventually – and only a few hours before the appointed time of detonation at 03:10 a.m. on 7 June 1917 – the ammonal charge was in place and secured by 120 metres (400 ft) of tamping with sandbags and a primer charge of 450 kilograms (1,000 lb) of dynamite. The Spanbroekmolen mine exploded 15 seconds late, killing a number of British soldiers from the 36th (Ulster) Division, some of whom are buried at Lone Tree Cemetery nearby.[35] The Spanbroekmolen British Cemetery is also close to the crater.

- Preparations for digging deep mines at Kruisstraat were begun by 250th Tunnelling Company in December 1915, handed over to 182nd Tunnelling Company at the beginning of January 1916, and to 3rd Canadian Tunnelling Company at the end of the month. In April 1916, 175th Tunnelling Company took charge and when the gallery reached 320 metres (1,051 ft) it was handed over to 171st Tunnelling Company who were also responsible for Spanbroekmolen. At 489 metres (1,605 ft) a charge of 14,000 kilograms (30,000 lb) of ammonal was laid and at the end of a small branch of 166 feet (51 m) to the right a second charge of 14,000 kilograms (30,000 lb) was placed under the German front line. This completed the original plan, but it was decided to extend the mining to a position under the German third line. Despite meeting clay and being inundated with water underground which necessitated the digging of a sump, they managed to complete a gallery stretching almost half a mile from the shaft in just two months, and a further charge of 14,000 kilograms (30,000 lb) of ammonal was placed. This tunnel was the longest of any of the Messines mines. In February 1917, German countermeasures necessitated some repair to one of the chambers and the opportunity was taken to place a further charge of 8,800 kilograms (19,500 lb) marking a total of four mines, all of which were ready by 9 May 1917.[39]

- The ground at the site selected for the Ontario Farm mine proved very difficult as much of it was sandy clay. At the end of January 1917 the 171st Tunnelling Company began to dig at Boyle's Farm which is just on the southern side of the main road (Mesenstraat/Nieuwkerkestraat) passing by. The shaft went down 30 metres (98 ft) and pumps were installed to bring air down and water out of the mine. After tunnelling forward, the miners broke into blue clay, extending the depth to some 40 metres (130 ft). After driving the gallery almost 200 metres (660 ft) forward, the flooding was so bad that a dam had to be constructed and a new gallery started. Despite these obstacles, the tunnellers arrived under Ontario Farm at the end of May 1917 and installed the 27,000 kilograms (60,000 lb) ammonal charge with a day to spare.[33]

- The farm, located next to the road from Messines to Ploegsteert Wood, was enclosed by a German trench system known as ULNA. Also at this point was a junction on the narrow gauge railway system which ran from the forward areas of Messines to the rear areas around Nieuwkerke, all of which made La Petite Douve Farm a natural target for a British mining operation. Work on a deep mine was begun by 171st Tunnelling Company at the end of January 1916, but the difficult geology lead to two mines being abandoned before completion. After a charge of 23,000 kilograms (50,000 lb) of ammonal had been put in place beneath the farm, the gallery was discovered by a German counter-mining operation on 24 August 1916. The mine flooded and was abandoned. After the war, La Petite Douve Farm was renamed La Basse Cour.[41][42]

- Work on the deep mine at Trench 127 was begun by 171st Tunnelling Company in December 1915. The name indicates the British lines where the initial shaft was dug, not where the mine was placed under the German positions. The shaft was completed to a depth of 25 metres (82 ft) within four weeks, however after driving a 310 metres (1,020 ft) gallery the Royal Engineers faced a sudden inrush of quicksand and a concrete dam had to be constructed. A new attempt was made, and by April 1916 the Trench 127 mine was ready, with the ammonal charges over 400 metres (1,300 ft) away from the initial shaft.[45]

- Work on the deep mine at Trench 122 was begun by 171st Tunnelling Company at the end of February 1916. The name indicates the British lines where the initial shaft was dug, due west of where the crater is today. The area was dominated by a complex of German trenches and by mid-May first charge of 9,100 kilograms (20,000 lb) of ammonal was in place at Trench 122 Left. Another shaft (Trench 122 Right) was started part way along the original tunnel and after another 200 metres (660 ft), a charge of 40,000 lbs of ammonal was placed by the Royal Engineers beneath the ruins of Factory Farm which sat on the German front line.[45]

Citations

- Lytton 1921, p. 97.

- Wyrall 2002, pp. 468–469.

- Edmonds 1948, pp. 35–36.

- Edmonds 1948, p. 36.

- Cleland 1918, pp. 145–146.

- Branagan 2005, pp. 294–301.

- Edmonds 1948, p. 37–38.

- Wolff 1958, p. 88.

- Liddell Hart 1930, p. 331.

- Sheldon 2007, p. 1.

- Wolff 1958, p. 92.

- Edmonds 1948, p. 57.

- Bülow & Kranz 1938, pp. 103–104.

- Edmonds 1948, pp. 52–53.

- Tweedie 2004.

- Edmonds 1948, p. 53.

- "Messines". Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Photo gallery: Battle of Messines Ridge". Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- Passingham 1998, pp. 61, 73–74 90.

- Edmonds 1948, p. 91.

- Edmonds 1948, pp. 91–92.

- Edmonds 1948, p. 92.

- Ailbhe Goodbody, "Tunnelling in the deep: Battle of Messines", in: Mining Magazine, 13 September 2016, London: Aspermont Media 2016 (online)

- Turner 2010, p. 53.

- Holt & Holt 2014, p. 193.

- Edmonds 1948, p. 94.

- Kuhl 1929, p. 114.

- Turner 2010, p. 44.

- Holt & Holt 2014, pp. 116–119, 247–248.

- Edmonds 1948, pp. 55, 60, 88.

- Bean 1933, pp. 949–959.

- Holt & Holt 2014, p. 248.

- Holt & Holt 2014, p. 249.

- Jones 2010, p. 150.

- Holt & Holt 2014, pp. 192–193.

- Holt & Holt 2014, pp. 193–194.

- "The Western Front Today – Kruisstraat Craters". Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- "With the British Army in Flanders: A Tour of Ploegsteert Wood Part 5 – The Kruisstraat Craters". Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- Holt & Holt 2014, p. 195.

- "Messines". Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- Holt & Holt 2014, p. 200.

- Jones 2010, p. 153.

- "Trench 127 in Battlefield Sites Forum". Yuku.

- "With the British Army in Flanders: A Tour of Ploegsteert Wood Part 12". Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- Holt & Holt 2014, p. 251.

- Pedersen 2012.

- "With the British Army in Flanders: A Tour of Ploegsteert Wood Part 11 – Le Gheer & The Birdcage". Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Location map". Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- "Battle of Messines Ridge". Clevelode Battletours. Archived from the original on 24 February 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- "The Western Front Today - Messines Mine 1955". Retrieved 2017-06-07.

References

Books

- Bean, C. E. W. (1941) [1933]. The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1917. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. IV (11th ed.). Melbourne: Australian War Memorial. ISBN 0-702-21710-7.

- Bülow, K von; Kranz, W.; Sonne, E.; Burre, O.; Dienemann, W. (1943) [1938]. Wehrgeologie (Engineer Research Office, New York ed.). Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer. OCLC 44818243.

- Branagan, D. F. (2005). T. W. Edgeworth David: A Life: Geologist, Adventurer, Soldier and "Knight in the old brown hat". Canberra: National Library of Australia. ISBN 0-642-10791-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Edmonds, J. E. (1991) [1948]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1917: 7 June – 10 November: Messines and Third Ypres (Passchendaele). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 0-89839-166-0.

- Holt, Tonie; Holt, Valmai (2014) [1997]. Major & Mrs Holt's Battlefield Guide to the Ypres Salient & Passchendaele. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-0-85052-551-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Simon (2010). Underground Warfare 1914-1918. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-84415-962-8.

- Kuhl, Hermann von (1929). Der Weltkrieg, 1914–1918: dem deutschen Volke dargestellt (in German). Berlin: Verlag Tradition W. Kolk. OCLC 695752254.

- Lampaert, Roger (1989). De Mijnenoorlog in Vlaanderen (1914–1918) (in Dutch). Roesbrugge, Belgium: Drukkerij Schoonaert. OCLC 902147968.

- Liddell Hart, B. H. (1963) [1930]. The Real War 1914–1918. New York: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-31652-505-7.

- Lytton, Neville (1921). The Press and the General Staff. London: Collins.

- Passingham, I. (1998). Pillars of Fire: The Battle of Messines Ridge, June 1917. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-1704-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pedersen, P. (2012). ANZACS on the Western Front: The Australian War Memorial Battlefield Guide. Richmond, Victoria: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 1-74216-981-3. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- Sheldon, J. (2007). The German Army at Passchendaele. London: Pen and Sword. ISBN 1-84415-564-1.

- Turner, Alexander (2010). Messines 1917: The Zenith of Siege Warfare. Campaign Series. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-845-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wolff, L. (2001) [1958]. In Flanders Fields: Passchendaele 1917. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14139-079-4.

- Wyrall, E. (2002) [1921]. The History of the Second Division, 1914–1918. II (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Thomas Nelson and Sons. ISBN 1-84342-207-7. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

Journals

- Cleland, H. (1918). "The Geologist in War Time: Geology on the Western Front". Economic Geology. XIII (2): 145–146. doi:10.2113/gsecongeo.13.2.145. ISSN 0361-0128.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Newspapers

- Tweedie, Neil (12 January 2004). "Farmer who is sitting on a bomb". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

Further reading

- Barrie, A. (1981) [1962]. War Underground. War in the Twentieth Century (Star ed.). London: Frederick Muller. ISBN 978-0-352-30970-9.

- Work in the Field Under the Engineer-in-Chief, B. E. F.: Geological Work on the Western Front. The Work of the Royal Engineers in the European War, 1914–19. Chatham: The Secretary, Institution of Royal Engineers. 1922. OCLC 613625502. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- Goodbody, A. (2016), "Tunnelling in the deep: Battle of Messines", in: Mining Magazine, 13 September 2016, London: Aspermont Media 2016 (online)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mines in the Battle of Messines 1917. |

- Tunnelling companies RE

- Database with technical specifications of the mines (Dutch)

- Messines Ridge photo essay

- AOH Appendix 1 The Mines at Hill 60

- Map of the mines

- Map of the mines (Google Earth)

- Messines with images of the craters

- With the British Army in Flanders

- Battle of Messines Ridge with images of the craters

- Discussions of mines that were not fired

- The Western Front Today, Messines